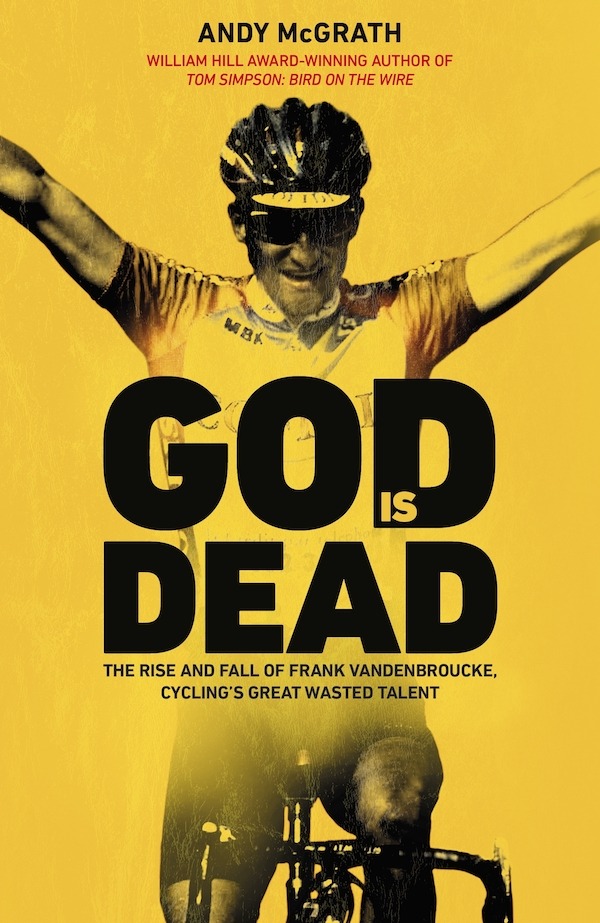

God Is Dead by Andy McGrath

A biography of Frank Vandenbroucke and a warning about celebrity.

The last book review combined cycling with Nietzsche but here “God Is Dead” refers to Frank Vandenbroucke, the Belgian cyclist who died in 2009, aged 34. For years he was venerated as more than a champion in his homeland, a celebrity with a touch of deity. Indeed they did call him “god”, but his autobiography refuted this with its title of Ik Ben God Niet (“I Am Not God”). Crucially, and similar to Eddy Merckx, Vandenbroucke straddled the linguistic and social divides of Belgium, a Walloon but from the border where he’d walk to school in Flanders and was fluent in Flemish. This helped his popularity, winning plenty did too but Vandenbroucke had that bit extra. He was photogenic and had a feline grace on the bike, he’d rock his shoulders a bit and his hips would twist when pushing a big gear but it didn’t look laboured.

Vandenbroucke became famous for the things he could do on a bike, and obviously this matters a lot in Belgium but he also became a celebrity, a personality who went from the sports pages to the gossip columns. The title is hardly a spoiler but it does mean Vandenbroucke’s death weighs on the book. Unlike “Chekov’s gun” on the table, here we know there’s going to be a death so you read wondering if events along the way are part of an arc leading to something; or just events.

The more obvious pattern is everything pointing to a career as a pro cyclist. He was part of a dynasty, his grandmother was the championne of France in 1926 and his uncle Jean-Luc Vandenbroucke was a prodigy who turned pro early. It’s not in the book but one detail about how Vandenbroucke tried to tilt things in his favour is his bed, he’d put a phonebook (remember them?) under each of the feet at the end of his bed so that he’d sleep with his legs raised slightly, the idea was this would help with recovery. Quaint given the doping regimes to come but here was someone living and sleeping cycling and if he’d been born a generation earlier or later perhaps things would have turned out for the better?

The early part of the book chronicles his effortless ascendency and there’s a lot here that you will read for the first time, especially in English. Vandenbroucke tried several sports, got into running but switched to cycling in his teens. Aged 14 he accompanied his father Jean-Jacques, a mechanic, to the World Championships in Chambéry and joined the pros for a ride in the Alps. “Who was the kid that rode with us? We couldn’t drop him” asked Claude Criquelion, “That’s my son,” Jean-Jacques replied.

The talent was great but this meant a bidding war with several teams racing to sign him and this rings the first alarm bell. He turned pro aged 18 which is still rare today, in 1994 it was sensational. It seemed justified when he landed a win in his first race, a Stage of the Tour Med. Only there’s no long term programme, they just want him for the results he can bring and the Lotto team, run by his uncle, desperately needed a top Belgian rider. In this era delivering results equated to industrial doping and the substance of the time, EPO, couldn’t even be detected for a long while. Vandenbroucke’s time in court seemed, like others, to bring him down to earth as practices tolerated, and even encouraged via the incentives on offer within the sport, were suddenly frowned on when made public.

What’s striking is just how out of control things were and yet nobody could stop it. Teams were paying him a fortune but there was little oversight, like buying Formula 1 car and parking it in the street rain or shine. You can’t diagnose via a book but the highs and lows read like bipolar depression only nobody was on hand at the time to help. We know this happened to many, we know Cofidis was a madhouse where management had all the authority of replacement teachers trying to teach a rowdy class as riders abused sleeping pills and alcohol. Several accounts from the late Philippe Gaumont to David Millar to Thierry Loder, the Swiss rider who couldn’t cope with the bullying and quit the sport – relate this but the book of course covers Vandenbroucke’s aspect, he had the pivotal role as a team leader, so talented he had to be indulged rather than sanctioned. Other teams were little better and the shadowy figure of Bernard Sainz lurks in the background. Once again when it comes to doping, entourage matters.

A series of teams but by now Vandenbroucke’s career is on a downhill path and each contract seems worse than the previous one, signed by both sides more in hope than reality. For all the sporting side, the book sets out the private, family life as well and this is all the more tragic. It’s one thing to see a career fade, another a father.

There’s no final reckoning on Vandenbroucke’s death. He died in a seedy hotel in Senegal and McGrath sets out events as best as he can. Matt Rendell’s biography of Pantani was able to pour over documents and witness accounts leading up to his death but VDB’s death happened alone on holiday and there’s less to investigate, besides the Belgian media’s trod the path already.

A thought experiment is to imagine what would happen if Vandenbroucke was of today’s generation. In between we’ve got the case of Tom Boonen who moved to Monaco, presumably attracted by the tax rates but also repelled by the Belgian media trying to pry into his private life and he was public property for a while, famous at the races but if he went to a shop or a nightclub it could be news too. The obvious case today is Remco Evenepoel, already “Remco” to the Belgian media in the way Vandenbroucke was “VDB” but apart from precocious talent and concern that Evenepoel’s every move is being tracked, you’d like to hope things are different today. But are they ever?

The Verdict

An English language biography of Franck Vandenbroucke, a page-turner even if you know it’s going to end in sadness. You might have read some of the stories and seen the results but this book covers plenty more, especially the early years. It’s a sensitive account, there’s no revelling in the amount of drink and drugs taken nor the money wasted, no hyperbole is used to pull in the reader. Given the bleak ending it’s hard not to read this constantly looking for clues as to whether his early years put him on an inexorable trajectory to a seedy hotel in Senegal while also wondering if moments along the way could have changed his tragic destiny.

Read to learn more about Vandenbroucke’s life and times, and also to be alert when a rider is feted excessively when they’re winning and blasted when they’re not.

God Is Dead is published by Bantam Press / Penguin.

A digital copy was sent free for review. More books at inrng.com/books

Vandenbroucke in the big time is before my time as a cycling fan so i knew nothing of him when he was competing.

So i have never understood the fasication / veneration of him. To me he’s just another from the big time doping period with a few big results.

In part it’ll be because in his best years he hadn’t been caught doping. Similar to Armstrong, Pantani and others, there might have been whispers but it wasn’t accepted public opinion that it was doping so he was hugely popular in Belgium. His court cases seemed to have been similar to Pantani’s legal issues as in once outsiders to the sport started investigating he was brought down to earth and publicly shamed. But, and you’d expect this, read the book to find out more about why he was so popular.

Got your point, but also worth remembering that Armstrong *was* caught and got a *backdated* TUE of sort, to start with. Then there was much more than whispers all the way through his seven Tours, but, hey… he was being tested so much, wasn’t he?

And in Pantani’s case, unlike what you suggest above, his fall came totally from within the sport (not only “politically” but technically speaking, too: the Carabinieri only got involved – and, back then in Italy, without legal reason of sort, by the way – once there was an over 50% test). As a sidenote, it’s worth noting that Rendell’s work, albeit detailed, is heavily dependant on police sources which are far from being unbiased in a case like this. A way better picture can be achieved reading a wider range of sources, several of them only available in Italian. “Why bother”, I guess.

It’s an irony of sort to now know what was actually happening in the sport while the likes of Pantani and VDB were being “publicly shamed”, indeed. In Pantani’s case on very feeble factual terms, by the way (if we speak in terms of sheer rules, of course).

I wonder if Armstrong’s rumours were that much stronger *because* the peak of his success came after/alongside VDB and Pantani’s cases? Certainly the rumours got louder and louder from the days of Indurain until Armstrong’s eventual downfall.

I’d even say that it was the other way around.

Armstrong’s version was being essentially accepted by most. Imagine that the “never tested positive” mantra is still alive today, in a form or another.

Even Sky, for example, endured some more serious media challenging.

During Lance’s seven Tours, the doubters weren’t given much space or positive public acknowledgement.

Let’s take a different case to show the sort of circumstances which people were going through: Manzano and Kelme. Until the Guardia Civil proved that Manzano was right, which only happened some two or three years later (crucially, Armstrong just retired), he was marginalised for his declarations and no media or institution took him seriously enough.

Manolo Saiz stood as one of the most important figures in cycling during the Armstrong era (I recall something like him participating in writing down the UCI’s ethical code :-O ) despite the mess during the Festina affair. Until Puerto, of course.

The likes of Pantani and VDB just coped or fit worse with that context on a personal or structural level, and the subsequent course of events was the by-product of the interaction between their personalities *and* a heap of social layers. A perfect storm of sort (while not a mere result of pure chance, not at all). Well, to be fair I must admit that I’m pretty acquainted with Pantani’s case, while I’m not as aware of every detail about VDB.

Well, to start with because cycling isn’t only about doping and a lot of it doesn’t rely on doping alone.

Otherwise… why do people even follow any sort of pro sport? ^__^

Exactly so.

“why do people even follow any sort of pro sport?”

I still wonder that, especially this pro sport. I’ve only started following this sport in earnest in the last couple of years. I used to follow it quite closely back when but after a period of increasing disillusionment finally gave up in July of 1996. Came back when the Telekom train faded, just in time for the Armstrong era. Came back on his retirement just in time for Landis and Contador and his tainted beef. Kept away for a time by rumors of TUE abuse. Back again now, half-expecting another shoe to drop. Clearly there’s something I find compelling in this sport. So, yeah, good question.

Thanks! I’ll add this to my ever-expanding reading list since it’s available for e-readers. FVdB always seemed to me to be the next incarnation of Freddy Maertens – amazingly talented but coddled too much? It was sad to see his decline, same with Maertens. http://cycleitalia.blogspot.com/2012/04/tour-of-flanders-museum.html

An interesting case, Vandenbroucke went through a lot of what Maertens did, but with millionaire contracts, more probing media and doping regimes that were as elevated as well, it all seemed to set him up for a much higher fall than Maertens, whose own autobiography in English is “Fall From Grace”.

No argument there! I enjoyed “Fall from Grace” a lot, one of the reasons I compared Maertens to FVdB and why I’ll be (eventually) be reading “God is dead”. But first I need to get through Beppe Conti’s “DOLOMITI Da Leggenda” which is in Italian, so a much slower read for yours truly.

It’s odd, now that I’m an old-fart with nothing to do all day but ride my bike, eat/drink the best food/wine in the world and read stuff like this…I seem to have less time than ever! My father-in-law said the same thing not too long ago, asking “How did I ever find time to go to work?” 🙂

What a strange career. Two great years with Mapei in 98 and Cofidis in 99, yet when at 26 in 2000 he should have been at the height of his powers it all suddenly fell away (from second ranked to ouside the top 500). Was it all down to his troubled personality, or had others caught up with his techniques, or maybe the UCI had caught up to his techniques too and he could no longer apply them.

On a personal note I would prefer to follow and admire a good honest rider than a troubled – and cheating – genius. But who were the good honest riders in the nineties?

David Moncoutié was a peer from the 90s and 2000s and a colleague of VDB at Cofidis too. He had some good results along the way, he’d have to pick his moments and crucially, similar to Christophe Bassons as well, just wasn’t that ambitious or competitive, a laid back streak. I’ve reviewed his book her partly because it felt right to hold up his book as well http://inrng.com/2014/02/book-review-ma-liberte-de-rouler-moncoutie/

Moncoutié is a pundit for Eurosport for France now, enjoys long bike rides and still takes Strava KoMs from pros. His son has started racing too.

The consensus (at least from a British perspective) was that Boardman was clean too, who knows what he might have achieved a generation later.

Perhaps the above works better reworded as “what he might have achieved a generation before”.

And perhaps it doesn’t given Simpson, Post and TI-Raleigh, and the overwhelming impression they made on British perception of pro cycling for a generation and more. Stick to what you think you know and leave the condescension in your own head.

@ Anon I don’t get your point. Until tranfusions, EPO and the more scientific approach to corticosteroids, GH and sexual hormones (curiously, people focus on testosterone only), I’ve got sort of the impression – backed by a handful of facts – that the advantage assured by whatever people decided to take, or not, was relevant, indeed, but not enough to reduce a potential champion, if riding clean, to a more or less marginal figure or supporting actor at most. Which means that perhaps a Boardman of sort, assuming he was essentially clean, might have achieved something more in previous decades, and I mean essentially more GP Nations and maybe some short stage race. Instead, I can’t see a scenario where he could be expected to achieve way better results from the 2000s on if sticking with the same supposedly clean ways.

Of course, one could also wonder if we’re speaking of 10 years (a sporting generation), or 20, or 30… but, frankly, mine was just a cheek-in-tongue remark about that naif feeling that the 90s were when doping made such a huge difference… unlike the 2000s of Armstrong, T-Mobile and Puerto? Or the original Sky mutant age -__-

However, as I said, I’d ask you to expand on what you hint at and its relation to Boardman’s hypothetical success in a different context.

Apart from the frequent koms, Moncoutié’s strava feed is interesting for the pictures and the regular banter

And going back just a few more years, Gilles Delion springs to mind, also leaving citing rampant doping as his reasonto leave the sport…

*Anonymous was me…

DJW sure we “prefer” to follow and admire “good honest riders”

Problem is every time we think we do something pops or eventually the too good to be true is proven

My rose colored specs shattered back with Pedro Delgado

As for the 90’s pick a top rider today & watch closely….who are the clean riders? Pog? Primoz? We will see 😉

“My rose colored specs shattered back with Pedro Delgado”

I could just about tolerate doping when it might (not always did) provide the marginal benefit as part of a compelling but flawed and very human sport. But when ability and effort become marginal and dope determinative, that’s not sport anymore — that’s a farce.

In retrospect, it was interesting seeing Ferrari’s (especially) efforts here, experimenting to see what worked, what didn’t, what sort of rider would respond well, using the Giro as the main laboratory in the early years. He started with traditionally promising material — Bugno, Rominger — and did well enough with them but he really broke through with some of the least likely people in the peloton: turning a 32 year old who might sneak a stage because he was half an hour down on GC into the Monster of the ’96 Tour? A 34 year old never-was into one of the elite climbers of the day? And he hit his peak turning a middling time trialler who couldn’t climb into a 7-time Tour winner.

Maybe even more interesting was the response. Ferrari wasn’t exactly circumspect in either his doings or his statements but nobody wanted to believe there was a problem.

Just as much a challenge as naming “the good honest riders” in any decade IMHO. Is “good and honest” someone who never cheated or just never got caught? Did they ever win anything so anyone would remember their names or just quietly work for the stars? Did they decide the pro ranks were just too dirty and stop before they ever got there?

I’m sure all of us count as “good and honest” – although the term good really can’t reflect our talent level…

Bobby Julich seemed to be fully clean, and I find Phil Gaimon a really interesting guy to follow these days. Also, there’s always the GCN crew – Daniel Lloyd is clearly an ex-pro who was clean.

But, at the top, I think right now it’s more important to watch the races with the understanding that it is not a perfect world. The sport is constantly evolving and competition requires deep pockets to get to the top – and top level technology and medical advice, unfortunately it’s a fact.

NB Bobby Julich confessed to using EPO, and left Team Sky in the wake of their zero tolerance purge.

Right, about Julich, I now remember that… (sorry, delayed reaction – I still have some memory issues from concussion last fall).

On another note, great for Girmay’s race this weekend. Was he also the guy on WVA’s wheel in his attack from E3 last week?

Gaimon was barely PT level, which is still very good, but his backing of Tom Danielson doesn’t do him any favors in the fight against dopers.

Meh, that’s not as important as he is a rider with a bit of influence.

Looking back 15-30 years ago and there were dozens of guys who doped to compete on the US National scene. Yet, when Gaimon raced it (rather successfully), he could clearly do it very cleanly. So that is some good news.

VDB is still venerated in Belgium. I was in a bar in Berlare in Flanders and met people who visit his grave every year on the anniversary of his death.

They showed me a bottle of VDB champagne.

And a memorial card from his funeral which they brought out as a sacred relic. You’d have thought it was The Crown of Thorns.

Vandenbroucke was from slightly before I was able to watch anything other than late night Tour de France highlights so I didn’t see any of his best moments. I have watched his famous Liege win and the Vuelta stage win where the Belgian commentator starts laughing at his attack (on YouTube). He seems to have been quite similar to Van Aert (or maybe more Van der Poel) in that he could do everything bar the big mountains, and when he was on form he appeared unstoppable. Modern cyclists don’t seem to have the destructive tendencies of 90s cyclists though. Or maybe it’s more that it’s so professional/intense from so early now that if you’re that way out you won’t make it to the top to start with.

Wonderful review. Chapeau, Mr. Inrng. This part made me smile:

“Unlike “Chekov’s gun” on the table, here we know there’s going to be a death so you read wondering if events along the way are part of an arc leading to something; or just events.”

You are so much more than a (racing) cycling blogger.

I had a quick look at the Wikipedia summary of his life and got the impression that damage to his knee from an accident in his teens might have had a bit to do with what came later.

Regardless of what was coursing through his veins, VDB was grace personified on a bike.