Peter Barry Hoban has died at the age of 85. One of the pioneering British cyclists, he made a name for himself in Europe with eight Tour de France stages, Gent-Wevelgem and more which made him arguably Britain’s best cyclist until the likes of Bradley Wiggins and Mark Cavendish surpassed his achievements.

Born in Wakefield in England in 1940, Hoban was one of five children in a cycling family and found a frame and parts in his father Patrick’s shed to build a fixed wheel bike. He joined his first club in 1954 and began racing the following year. As well as insisting on riding to school, he began racing on grass tracks and in the prolific time trial scene, an era when road racing was near-prohibited on British roads.

Hoban took inspiration from the road, he read of fellow Yorkshireman Brian Robinson (pictured) becoming the first Briton to win a stage of the Tour de France and told the Velo101 website he fancied some of this.

As author William Fotheringham writes in Roule Britannia – which has a Chapter dedicated to “the Grey Fox” – he even persuaded his Calder Clarion cycling club to put a stitched panel on the front of the jersey saying “Calder” to resemble a continental racing jersey, and got his mother to embroider his shorts to further the look.

The combination of time trials and track racing including the British pursuit title led him to the Rome Olympics where he was part of the team pursuit. He might have been too strong for the British team, at least he told Cycling at the time, shouting he was going to do a long turn and this effort sapped his team mates such that they struggled to follow. All this was a way out of his electrician’s apprenticeship.

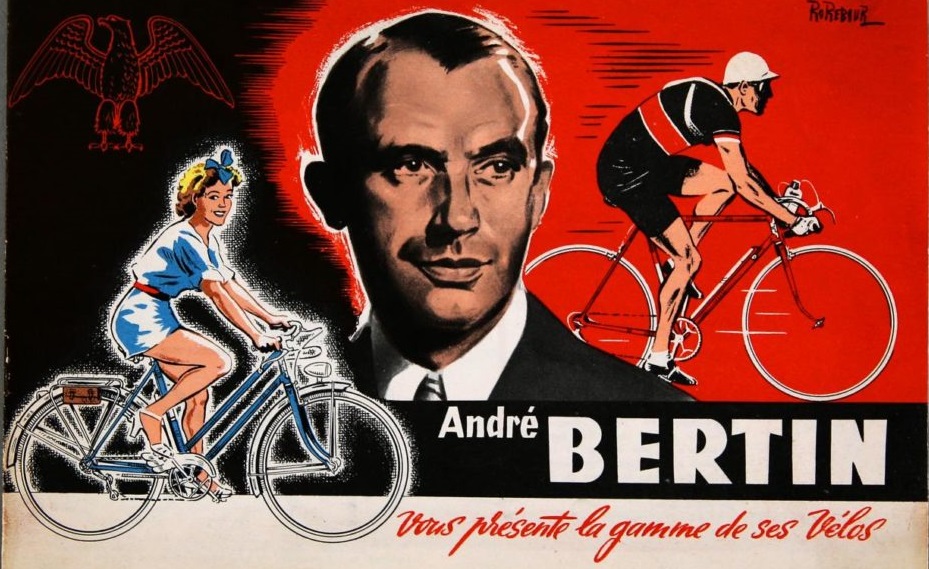

Inspired by Tom Simpson, two years his elder, Hoban headed for France. He spent two seasons as an indépendant, a semi-professional, with André Bertin’s team in northern France. Bertin was an ex-pro making bikes and gave the right riders a bike and pay in exchange for publicity. Hoban told Cyclist magazine he ate countless omelettes because it was one of the few dishes he could recognise on a menu.

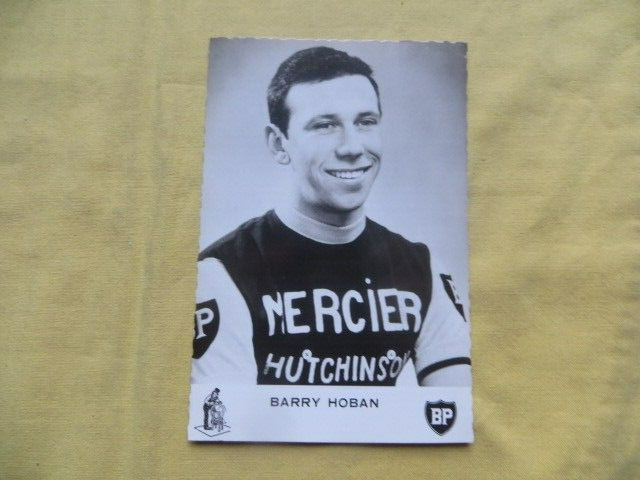

Helped by a second place in the Tour de l’Avenir’s time trial stage and a good word from a journalist, he signed for the Mercier-BP team for 1964 led by Antonin Magne, the superstitious smok-wearing manager who kept a pendulum in his pocket to dowse rider ability.

Success came early, two stage wins in the Vuelta that spring from breakaways, after helping his team leader Raymond Poulidor to the overall win while team mate Frans Melckenbeeck also got three stages in the sprints. A stage in the GP du Midi-Libre soon after and then he rode his first Tour de France as a neo-pro where he finished second on one stage to André Darrigade, one of the all-time best sprinters but then aged 35 and apparently benefiting from a helpful handsling.

Hoban’s team leader Poulidor also finished second overall that year. The two were friends, often rooming together. Fluent in French, Tour de France historian Jacques Augendre wrote Hoban was “the most French of the English”, even mastering Parisian slang; for Fotheringham this was more because Hoban had learned colloquial French from his peers rather out of a textbook.

Whether second placed or not, Poulidor often finished ahead of the two so Hoban joked he could count a freshly brewed pot of tea and ready-buttered slices of toast in the hotel room. This was the ready supply of stereotypes for French media in an era where an Englishman in the peloton was rare; think of Tom Simpson posing in a bowler hat with an umbrella.

Indeed in the 1964 Tour de France every starter either came from France, a country bordering France or the Netherlands, except for Britons Hoban, Tom Simpson and Michael Wright, plus Irishman Shay Elliot; and Wright didn’t speak English having grown up in Belgium. Only one British journalist, John Wadley, covered the Tour de France.

In 1965 Hoban was instrumental in chasing down the breakaway in the World Championships so Simpson could win. Both lived near Gent in Belgium, and as Fotheringham writes Hoban would often visit Simpson’s home.

1966 saw the Poulidor vs. Anquetil rivalry reach a new intensity Paris-Nice when the Mercier and Ford teams clashed, to the point where it was alleged Anquetil’s Ford team mate Jean-Claude Wuillemin barged Hoban off the road, forcing the Briton to abandon the race. Hoban, by definition in the Poulidor camp, could see, and often did point out, the Frenchman’s mistakes.

In 1967 Hoban’s first Tour de France stage win was the one he least wanted. Tom Simpson had died on Mont Ventoux and the next day, after a minute’s silence at the start, the peloton agreed that a British rider would be allowed to win. Hoban said he got a gap at one point and then pressed on to win for Simpson, a moment appreciated by many at the time. He later said it was not even a victory, just a tribute.

Only his account was disputed later. Rather than continue in the race, some of the British riders wanted to go home as British team mate Vin Denson told Le Vif but Hoban wanted to stay. Acting as the elder statesman in the bunch, Jean Stablinski picked his Bic team mate Vin Denson to be the day’s winner and advised he should go clear with 20km left in the stage. Only Hoban pre-empted this. As Denson told Le Vif and also Fotheringham, Stablinski told him to chase but the British team could hardly be seen to ride down one of its own. A betrayal? Possibly and Denson says Hoban and not him got lucrative criterium invites but we can’t imagine Hoban’s state of mind the day after his idol, friend and neighbour had died; Hoban said he woke up in the night feeling as if it was all just a nightmare only to be confronted with the reality at dawn.

Later that year he finished second to Rik Van Looy in Paris-Tours, then a prime race and Hoban’s palmarès was growing. For all the wins and there were plenty, he would also have many places d’honneur like third in Paris-Roubaix and Liège-Bastogne-Liège and fifth in the Tour of Flanders too.

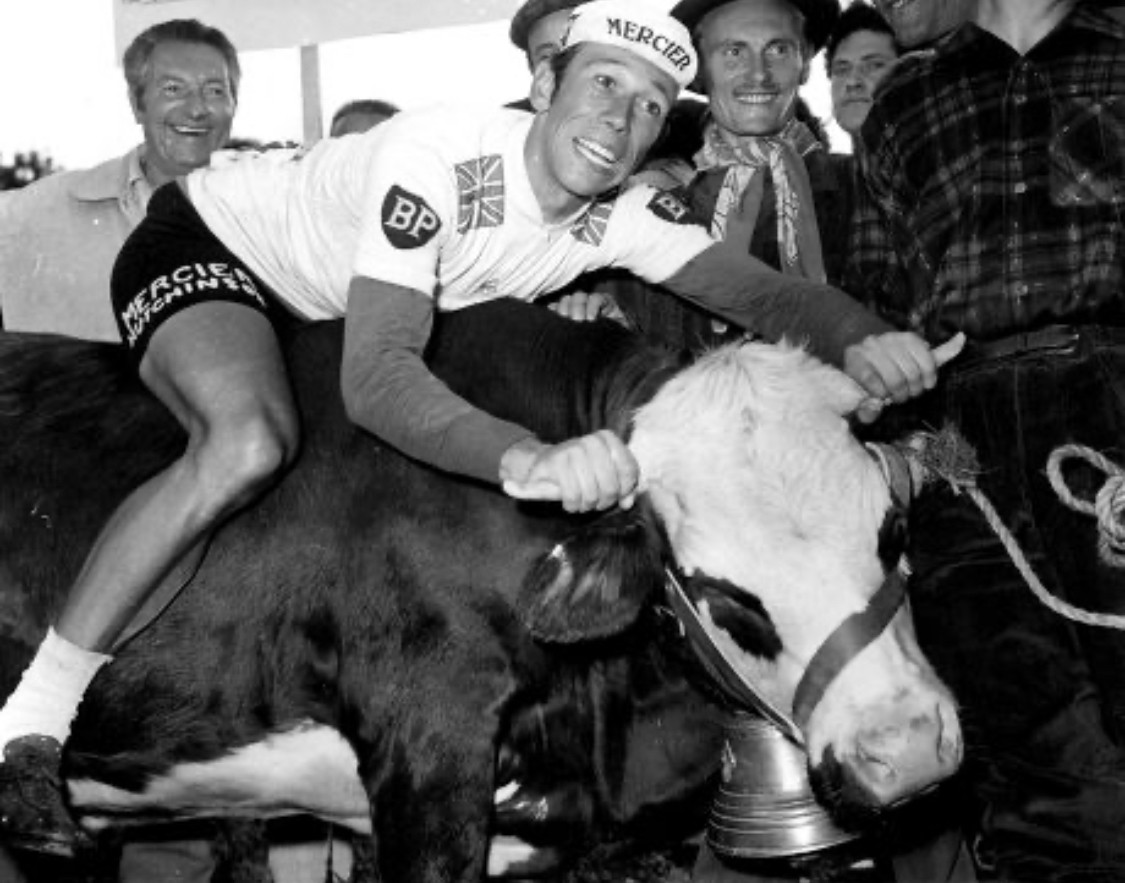

1968 Hoban took a mountain stage win in the Tour de France, a long solo raid over the Aravis and Colombière passes. The newsreel of the day says he went for the first intermediate sprint and then kept going, quickly building up a ten minute lead. But the next day’s L’Equipe also cites the Spanish team saying Hoban had asked for permission to go up the road in order to urinate, only to disappear for the day. Either way, he was first to the finish in Cordon and won a cow as a prize.

He was recognisable in the cycling press, a beaming smile with a mouth that looked like he could eat a whole croissant sideways. But no clown, and as the wins came more often and he was an established lieutenant who had the finishing speed to pick off wins but also an attention to detail, insisting on meticulously checking his bike and clothes prior to major objectives.

In 1969 Hoban took two consecutive Tour de France stages, a first since Fausto Coppi in 1952. He later credited some of this to his recovery powers:

“I soon found out I had an attribute which was paramount for a Tour de France rider. My recuperation was amazing. I could ride a stage, get smashed to smithereens, sleep the night, the following day I was brand new again… …I was wanting the Tour to go on another week”

Cycling Weeekly video interview, 2021, Youtube

In December that year he married Helen, Tom Simpson’s widow with whom he’d later have a daughter. A more private chapter of his life, Hoban took on a protective role for his two step children who grew to see him as their father.

In an interview with L’Equipe Joanne Simpson said at the time they were used to their father Tom’s long absences away at races and were never quite told he had died, to the point where a young Joanne asked her mother how she would explain the marriage to Hoban when Simpson eventually returned.

The new start also saw a change of team, leaving Magne for the Sonolor team in 1970. More wins came, like the Four Days of Dunkerque and the GP Fourmies.

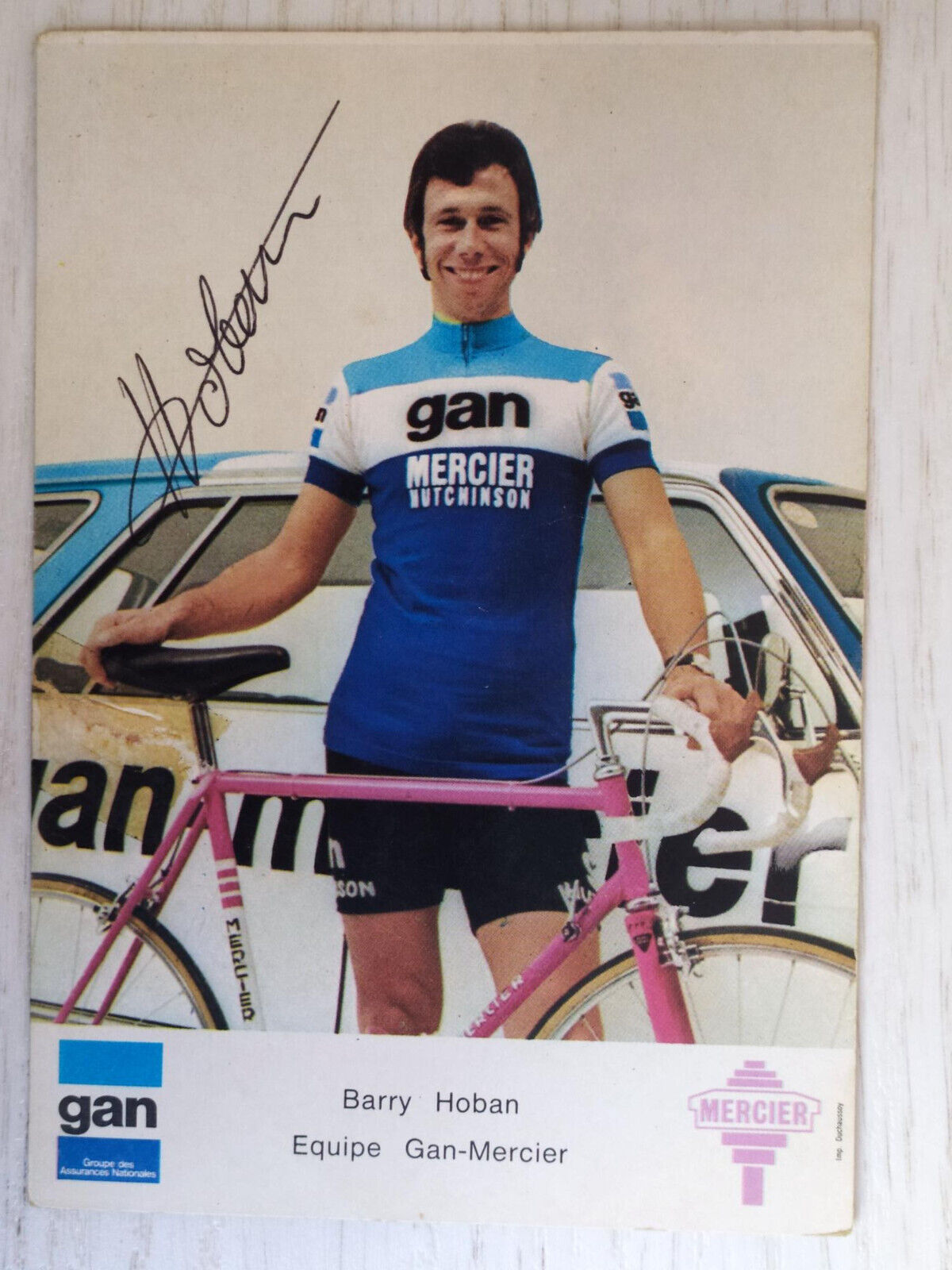

In 1972 he rejoined Magne whose team had added insurer GAN as a new sponsor, and Bernard Sainz as a directeur sportif. Hoban was teaming up again with Raymond Poulidor but also Cyrille Guimard who briefly became a rival to Eddy Merckx at the Tour de France before a ruined knee forced him to concede, then quit.

In 1973 he took a stage in Bordeaux where L’Equipe’s Antoine Blondin deployed the line “Dernier Tango de Barry” riffing on a film title… only for Hoban with his recovery powers to win again in Versailles.

In 1974 Hoban won Gent-Wevelgem, beating Roger De Vlaeminck and Eddy Merckx. A memorable win, he could recount the moment in several interviews where a gap opened in the sprint and he went for it. This was also the year that the Tour de France made its first visit to Britain and Hoban was marked for the one stage to finish ninth; instead he won in Montpellier, then again the next year in Bordeaux and continued with the same team until the end of the decade at the age of 39, more than mature for a pro then.

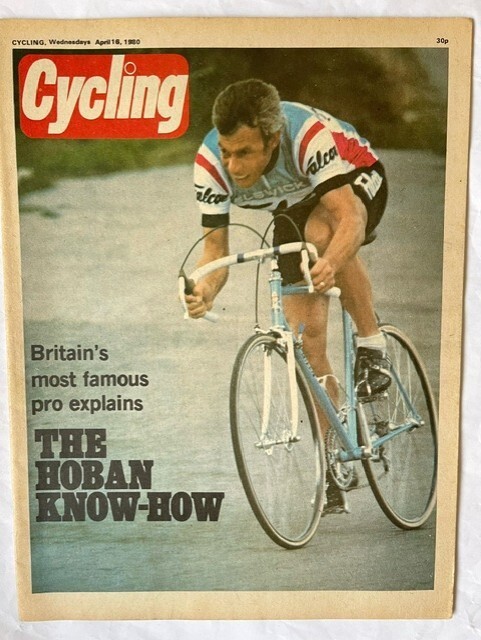

Hoban moved back to Britain where he raced his last year as a pro in 1980 for the Falcon team. Then he worked in the cycle industry, promoting Hoban-branded Coventry Eagle bikes and later working for importers and distributors.

His 36 pros wins made Hoban one of the best British riders of the 20th century. Simpson had quality like the Worlds, later Robert Millar would shine in stage races but Hoban was the most prolific. This was a door-opener in the cycle trade “the cognoscenti knew who I was but nobody else did” he told Cyclist and this lament at the lack of wider recognition was something he mentioned several other times as he saw a new generation of British cyclists thrive and begin to overtake his achievements but this time in an era when their exploits were televised and they became household names.

“My one big regret is not the question of money, although I could have made a lot of money today, but the fact that I am not known for what I did over there. No one knows who the hell Barry Hoban was. It would be nice to be known for what I did for the sport, and not pushed into oblivion as if it didn’t count. When I go back to the Continent it’s like the return of the prodigal son. I go to the Ghent Six and straight away everyone says, “Ah, Barry’s here.” It’s a nice feeling.”

Barry Hoban, in “Roule Britannia” by William Fotheringham

When the Tour de France came to Hoban’s Yorkshire in 2014 a plaque was unveiled in Wakefield. “I reminded them it was 33 years since I stopped racing,” he told Cyclist, adding “but I’m grateful“.

Grass tracks? I didn’t know there was such a thing.

Still popular at many Scottish Highland Games.

Grass track racing still a popular thing here in Yorkshire – https://westridingtrackleague.com/

Fixed wheel, cyclo-cross tyres and a great deal of fun.

A really good way of picking up bike handling skills that many miss out on these days.

A certain Laura Trott (as was) grew up on the grass tracks of East Anglia and she turned out OK.

The Austral Wheel Race, the oldest track race in the world, started out with its early years being contested on grass at the Melbourne Cricket Ground before shifting to velodromes.

The contact with the Bertin team came about through Ron Kitchen, a famous British name in the cycle industry at the time, who imported Bertin frames.

Grass track racing was very popular in the 60s. Every coal mine held its own ‘Gala’, and grass track racing was almost always on the programme. Sadly, like Barry now a thing of the past.

RIP Barry. You were an inspiration to many.

Ron Kitching imported all sorts of kit and sponsored Beryl Burton amongst others.

Egremont Crab Fair in Cumbria also had highly competitive grass track races where local – and olympic – star Mike Cowley would often clean up.

Hoban just looked the part on his pink Mercier as the Cycling photo shows. He wasn’t outdone for style even in the era of Moser, Merckx and De Vlaeminck.

Hoban informally imported things too, bring back pro kit to sell to locals. A small side business but it might have helped later when he went into this business as well.

It’s not just the tennis courts in Britain that have grass, velodromes too or sort of with the grass tracks, including some banked ones like this.

Looks much safer than racing on a wood velodrome: I’d rather a crash led to a few grass and mud stains, rather than a body full of splinters!

There is still grass track racing at Roundhay Park every Monday night during the summer.

I ran a bike shop in the UK for 25 years, Barry called on me as a rep for Yellow, selling Assos clothing. He was the last of the ‘gentleman’ reps. Always on time, always knowledgeable about the products, and always a pleasure to deal with. His achievements are outstanding, when you look at when they took place, almost unknown to make the move to continental Europe in those times. I mentioned to him I was going to go to France to ride my bike. The next day I received 31 pages of faxed details. Not just areas to visit, a whole itinerary, including the names and contact numbers of all the best vignerons, many of whom he knew personally. We had a fantastic time, Barry will be missed by many.

Thanks for sharing this, great anecdotes. I quoted the Tour de France historian Augendre above, he also said Hoban was into his wines and especially champagne and beaujolais but 31 pages is great.

That sounds like a holiday itinerary I’d like to investigate. How old is the list?

This was really nice to read.

Would also love to see this holiday itinerary, do you still have? Can it be scanned and sent to INRNG?

What a lovely thing to read! Thanks for sharing your memories.

Excellent story Inrng – thank you for sharing this. Touching that he married Tom Simpson’s widow so they could take care of each other and Tom’s kids.

Thanks

I’m assuming the deadname instead of Philippa York was a mistake?

Please take your grievance mongering elsewhere.

Anonymous 2, let’s cool it rather than begin a verbal bar brawl below an obituary.

Anonymous 1, I’d greet Philippa today but as the results were recorded as Millar so wrote it up like this.

Philippa has mentioned she wanted it to be recorded that way (to Fotheringham, quoted in Roule Britannia)

He came to ride with our club on a Sunday run the once – I think our contact was through the bike club sponsoring us. He rode alongside all of us and chatted all the way through.

Really nice guy and had stories to tell by the dozen.

I absolutely love your obituraries. Learn so much about cycling history that I wasn’t aware of. And the writing! ‘…a beaming smile with a mouth that looked like he could eat a whole croissant sideways’…wonderful. Thank you.

Somehow only seen grim faced winning Barry before and I had definitely not seen that cow picture before and it certainly fits the quote

A lovely tribute, thank you.

He writes in his book (long out of print, William Fotheringham tweeted an image of the cover the other day) that he lost the 1964 TdF stage on the old track at Bordeaux because the team mechanics put the wrong tyres on his bike, against his request. There’s various stories in there about Magne being a right cheapstake, like not having zips on the jerseys because they cost an extra franc. There was redemption of sorts when he won on subsequent visits to Bordeaux, doing so as late as 1975. There’s a great photo of him yelling in delight on the line as he comes through in the sprint.

Stood next to him in the Wetherspoons next to Leeds Arena before the team presentation at the 2014 Grand Depart, let him get served ahead of me, he ordered a pint of bitter and a glass of wine (presumably for Helen)

A

Any word on funeral arrangements yet? Will it be a public event? I think there are more than a few old bike riders who’d like to pay their respects to a guy who beat a path hundreds like me tried to follow.

Lovely piece this, thanks

This is a really excellent piece and a pleasure to read.

Thank you.

also – ‘Antonin Magne, the superstitious smok-wearing manager who kept a pendulum in his pocket to dowse rider ability’ – this guy!

Thank you inrng-a very fitting tribute and inspiring reading.

With this loss an era is almost over. Vin Denson, Michael Wright and ,I think, Bob Addy are the remaining riders from the 1967 Tour still alive.

The stories left and also written about from then are memorable and inspiring. Many others attempted to follow before and after Hoban and Simpson achieved such success.

Not all succeeded but tried just like the UK youngsters are doing today. And with great success.

Wonder if these riders do feel like they are today’s Hoban and Simpson et al- hope so.

Thank you again.

Quick question, maybe I am wrong. But I thought Poulidor first raced the Tour in 1962, and Barry first raced it in 1964? Am I wrong? The text is a bit unclear, maybe this is what you were trying to say and I have misread it.

By the way, Barry was a very fine rider. I guess the modern equivalent would be someone like Mads Pedersen (would that be right?). Someone with a good sprint; good enough to win on a tough course, but not really someone for the “proper” hills (I hope this sounds positive, it is meant that way).

Thanks, have fixed the text above. Poulidor first raced in 1962 and finished third, then eighth, then second with Hoban.

It’s hard to compare riders, but I might look to someone with more of a track and time trial background but harder still to think of name to use, especially who might also win a mountain stage and enjoy such a long career. Almost think of Geraint Thomas v1.0 before he switched to become a stage racer but still hard to match.