Raymond Poulidor died on 13 November, aged 83. A champion cyclist, he made a name for himself as a loveable loser, a moral winner and a dependable emblem of rural France during a period of societal change. His reputation reaches far beyond cycling and there are Poulidors in sport, politics and life.

Born in 1936, the year of the Front Populaire, he was the youngest of four brothers and was raised in rural poverty. “I will never know if my arrival was a happy moment or one of those calamities that happen so often… one more mouth to feed or another pair of arms to work with?” he told a biographer. His parents were métayers, renting farmland in exchange for a share of the crop they produced each year. His childhood saw Nazi occupation – aged six he was ferrying grenades to resistance fighters under the cover of fishing trips – and food shortages, but he enjoyed cycling. He borrowed his mother’s bicycle to mimic his brothers who had started racing. He soon bettered them and was winning races across central France as a teenager.

Compulsory military service when he was 20 meant two years in Germany and Algeria he returned 15 kilos heavier and set to work again on the bike during the winter of 1958-59. He found form by the summer and started a race in Peyrat-le-Château, a short ride from his home. He was up against professionals like Jean Dotto, fourth in the 1954 Tour de France and winner of the 1955 Vuelta a España, and Bernard Gauthier, a former French champion and Bordeaux-Paris winner. Dotto won while Gauthier got lapped several times by Poulidor. Gauthier told his team manager Antoine Magne that he’d discovered a “rare bird”. Magne, a Tour de France winner, had become one of the top managers and had views on training and recovery that were ahead of his time, but he was also enigmatic and superstitious, using a pendulum to dowse the health and ability of his riders (knowingly mocked in a scene of Le Vélo de Ghislain Lambert). Magne and Poulidor shook hands rather than signing a contract and an 18 year career as a professional began. Long by today’s standards, exceptional for that era and it meant he’d race against the likes of Louison Bobet, Jacques Anquetil, Eddy Merckx and Bernard Hinault. No wonder he finished second so often.

Poulidor is famous for being the “Eternal Second”. He still enjoyed victories galore, indeed he won 153 races and finished second 65 times. As a second year pro in 1961 he took Milan-Sanremo with a solo win. He’d go on to win the Vuelta a España, Paris-Nice, the Dauphiné, the French championships, the Flèche Wallonne, the Midi Libre stage race and seven stages in the Tour de France. Yet he didn’t win the Tour de France. It wasn’t for trying, he started 14 times, finished 11 and stood on the podium in Paris eight times, but never the top step. He never wore the yellow jersey either, not even for one a day. He fell short by 0.8 seconds in the 1973 prologue to Joop Zoetemelk, cycling’s other eternal second for his six second places in the Tour.

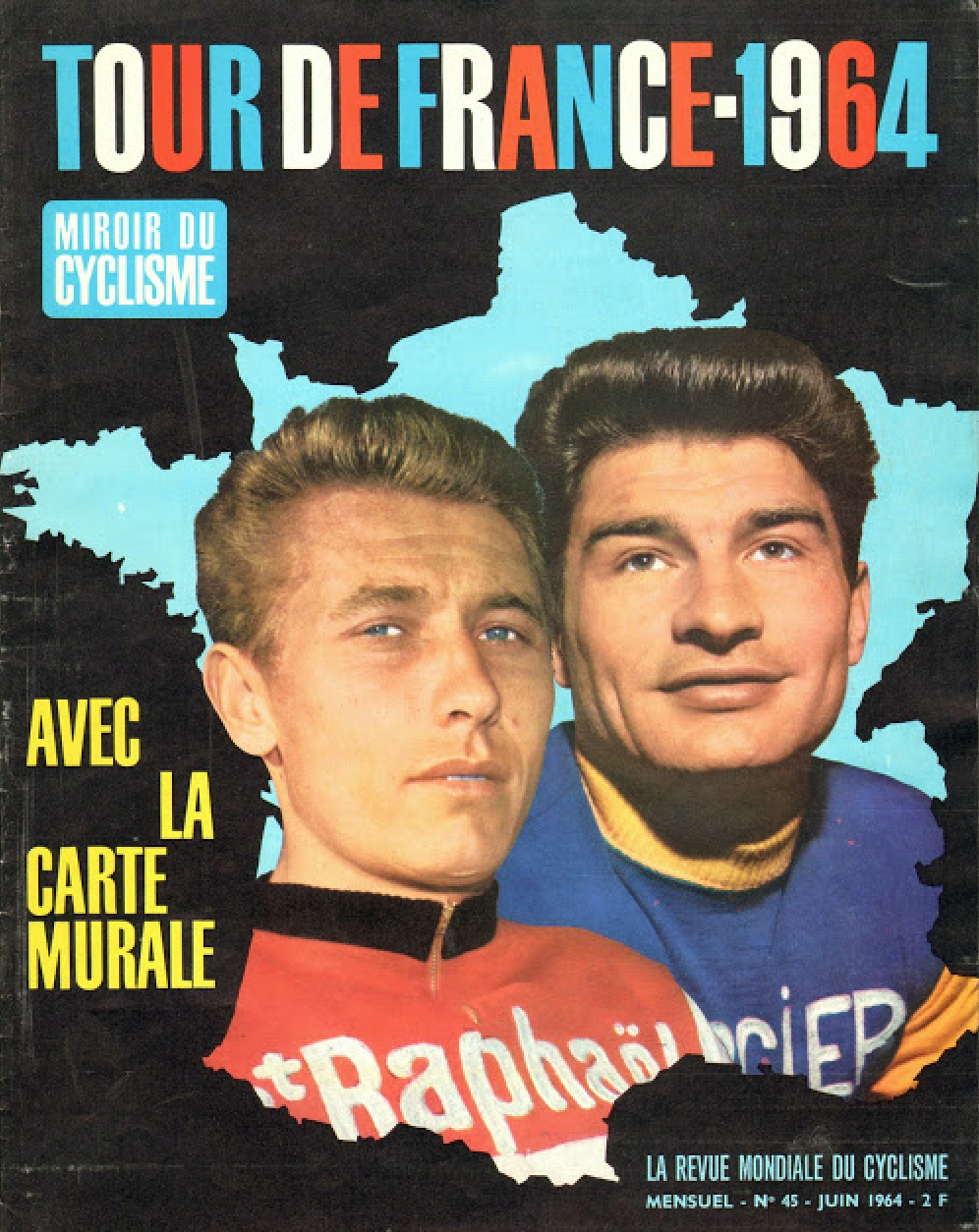

Poulidor turned up for his first Tour de France in 1962 with his hand in plaster and lost eight minutes on the opening stage but still managed to finish third overall which saw him celebrated for his courage, what playwright and sports columnist Antoine Blondin labelled Poupou-larité in a nod to his affectionate nickname. Often unlucky, he sometimes brought misfortune on himself. The 1964 Tour de France makes a good case study. Stage 9 finished on the athletics track in Monaco only Poulidor blundered and sprinted for the line after one lap when they were supposed to complete two, leaving arch rival Jacques Anquetil to pip him in the sprint the next lap and collect the one minute time bonus. Later, on the stage to Toulouse, a puncture and crash caused by his mechanic would cost him more time.

With two stages to go Anquetil was leading by 56 seconds but faltering as he’d done the Giro d’Italia weeks before and the final week of the Tour was close to cracking him. The upcoming summit finish on the Puy de Dôme should have been the moment for Poulidor to strike back. But the mountain would be too much.

“I lied to Antonin Magne. He’d asked me to go and check out the Puy de Dôme. I had 42×24, too big. At the stage start in Brive, when he saw Bahamontes had fitted a 25 tooth sprocket, he asked if I’d been to see the climb, yes or no. I didn’t dare tell him the truth. But in those days we had such small salaries and three days before the Tour we rode criteriums.”

– Raymond Poulidor, L’Equipe 8 July 2013

Instead of a recce Poulidor rode a criterium for cash. In today’s context it sounds unforgivably greedy but then riders earned income from criteriums rather than team salaries and his decision was understandable. Locked in combat, the moment was immortalised in that image but Poulidor managed to put 42 seconds into Anquetil but days later lost time in the final stage of the race, a time trial from Versailles to Paris. Did the Monaco mishap and the gearing cost Poulidor the race? To tot up a ledger of gains and losses would be to miss the point: Poulidor looked stronger and became a public hero for it.

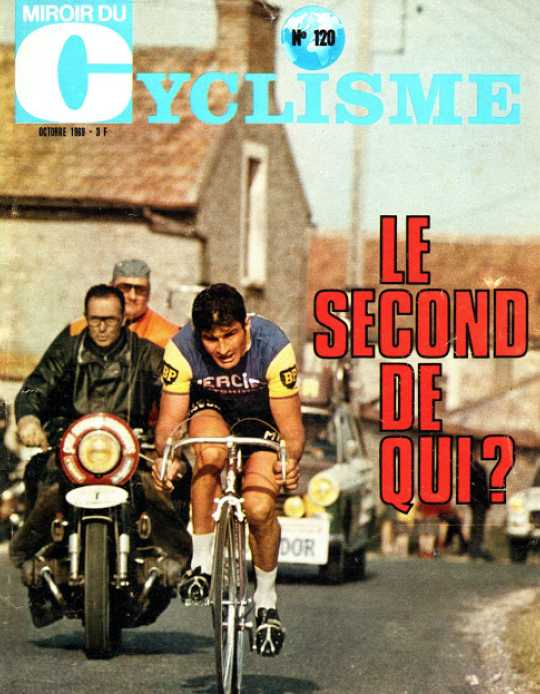

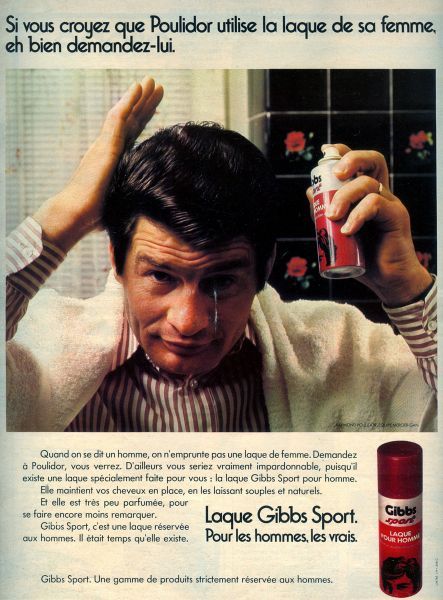

Finishing second was his trademark, Miroir du Cyclisme’s 1969 end of season cover asks who he’d finish second to next year (answer: Eddy Merckx). Poulidor wasn’t a loser, he was often proclaimed the “moral victor” of many races, wildly popular with the crowds who found Jacques Anquetil’s winning ways cold and economical, “like a diner who rushes out of a restaurant without leaving a tip” quipped Blondin. A decade on from Coppi and Bartali, France had Anquetil and Poulidor: a sporting rivalry with an undertone of social change during the Trente Glorieuses. One part of a rapidly modernising France could see themselves in bourgeois Anquetil as he posed in sharp suits and sports cars to a soundtrack of Johnny Hallyday singing America’s Rockin’ Hits. Another part of France preferred the accordion and cherished Poulidor as the valiant and reliable peasant, a product of terroir with his local accent.

These labels were caricatures. Poulidor might have grown up on a farm but lived in a modern concrete villa rather and drove a Mercedes, not a tractor. He would front ad campaigns for male grooming products. Cyrille Guimard tells in his autobiography that Poulidor was a shrewd investor. Pre-season training camps saw riders pay for their board and in the evenings Poulidor would challenge team mates to a card game and invariably won, accumulating enough cash to pay the hotel bill by the end of the week. Money seemed to motivate Poulidor, for example Eddy Merckx was the full cannibal in the 1972 Paris-Nice, dominating, going for intermediate sprints, tussling for bunch sprints and with one stage to go, in the overall lead too. The prize that year was a motor boat and Merckx was so confident he posed for a photo session with “his” prize on the morning of the final stage. But race organiser Leuillot needed some drama and offered Poulidor 10,000 francs if he won. Poulidor stormed up the Col d’Eze to win the race and deny Merckx.

Later in retirement Poulidor wondered aloud if winning the Tour de France would have ruined things. There’s a book to be written about French attitudes to sport and how valiant loss is often celebrated more than a calculated win. Arguably a victorious Poulidor would still have been popular because of his humility and rural charm: the model grandfather. Still, to be the perpetual runner-up turned Poulidor from a surname into a noun: Michel Rocard’s failed bids to become President saw him labelled as “the Poulidor of politics” and the term is regularly applied to any runner-up.

When Laurent Fignon climbed in a taxi to be asked “are you the guy who lost the Tour by eight seconds”, he rapidly replied “Non monsieur, I’m the one who won it twice”. Poulidor by contrast would go on TV chat shows to endure gentle mockery from urbane Parisian hosts without the need to bring up Sanremo or the Vuelta. Equally he avoided saying anything controversial, which helped keep him popular. He enjoyed his status, he even seemed to crave it and spent many years on the Tour de France caravan where the crowd, especially the senior element, loved him. He was like a hit record or a vintage car, people enjoyed the comforting nostalgia he supplied. He adored the public too, telling Jean-Paul Ollivier on France-Info radio in 2015 that he couldn’t bear the thought of the day when he walked down the street and people didn’t come up to him. He was feted by the Tour de France with a stage start in his home town of Saint-Léonard-de-Noblat in 2004, and in 2013 the town unveiled a statue of him. If he liked recognition this must have been a joy because it was placed halfway between Poulidor’s house and the town square, the daily trip for a newspaper or baguette meant passing the monument.

Recently he enjoyed a new label. His daughter Corinne married Dutch professional Adri van der Poel and so the Eternal Second became the grandfather of Mathieu van der Poel, and he was very proud of this too. Poulidor kept a close eye on the sport and as a guest on Europe 1’s Club Tour radio show last July proved a sharp pundit with views on Egan Bernal and Julian Alaphilipe that were quickly proved right in the Alps.

Cycling changed everything for Poulidor, “without a bicycle my horizon wouldn’t have been much further than the hedge at the end of the field”. Poulidor’s secret was that he knew this and never lost sight of the fields where he grew up.

Thank you INRNG. a fine and fitting obituary to a very special person.

At some level the final paragraph applies to everyone who has ever ridden a bike.

RIP.

++1

++1

Lovely piece. Thanks.

Lovely appreciation, INRNG, and you sure can see the shared genes in that final photo.

I see Poulidor in Mathieu, the cheekbones and the wide mouth.

I always felt that Poulidor and Thevenet were of a pair, though twelve years separated them. Poulidor’s career was so long that they overlapped considerably. Despite no great formal education they both enriched cycling commentary here in France with deep knowledge, the right words, thier style showing a background on the land, and, above all, modesty.

I’d tend to agree, Thévenet’s always got a kind word to say, his “problem” was that he actually won the Tour and so got booed for this at times by a section of the crowd and his career was shorter. Both come from rural parts of central France famous for their beef cattle (Limousine and Charolaise) and as you say remain modest and available to the public and media alike.

Nice and fitting obit – thanks for turning this out so quickly. Poulidor’s palmares always come as a slight surprise given his reputation as the eternal second – just shows how much the focus on the Tour distorts the truth.

I wonder if sportsmen will ever be as well known again in that their name has a meaning and is used for things nothing to do with their profession. ‘Back in the day’ when there were only a couple of TV channels and any sport shown live had much less to compete against and had a guaranteed massive audience share certain sportsmen seemed to be known by everyone. As an example anyone in 1980’s England knew who Ian Botham was, now most people would struggle to name any professional cricketer. Poulidor seems to be a kind of French equivalent, a national institution.

The motto of Antonin Magne was : “La gloire n’est jamais où la vertu n’est pas” (Glory is never where there’s no virtue), from an old french poem of the 18th century.

Magne’s an interesting character. There’s been a lot of lore about sport and things to do and not do and some of it is bunkum but some of it turns out to be backed by sports science. Magne said “the Tour is won by sleeping”, an early nod to the importance of sleep and rest for recovery, obvious perhaps but he insisted on his riders sleeping in an era when it wasn’t considered good; he’d recommend a hot bath on a rest day and this helps riders sweat and so prevents water retention etc. When riders were going very well they’d get the right to a bottle of “white water” which was mysterious but turned out to be water with some sodium bicarbonate (aka baking soda) inside which is used today by some. Race-wise though he was conservative tactically.

Intersting! In the Netherlands Joop Zoetemelk is credited with the quote that “The tour is won in bed” but it seems he got it elsewhere.

Lovely piece and fitting memory to a true gentleman. RIP

Bloody hell you can write! A lovely piece thanks.

You must be new here. He’s the best in business.

A fitting reflection on one of the essential characters in our shared cycling heritage. INRNG still managed to make it a school day. I now know more about US financial aid to Europe than I knew there was to know. 😉

Lovely piece, but no great surprise, he’d been ill for a while. He couldn’t beat Anquetil, but finally he beat Merckx. 🙁

He was everything good about cycling: approachable, humble and someone every fan could relate to. Cycling does well in that respect, we can ride the same roads, appreciate the effort required and look on our icons with renewed admiration. There’s nothing remote about the sport.

RIP Raymond.

That was a nice read. Thanks.

Thank you InRng, and thank you too, Raymond.

Another great piece, thanks so much.

Another thought: the photographs of Poulidor racing – and of other climbers of his epoch – makes a marked contrast with the diet and weight obsessed current crop. Maybe power/weight ratios were not optimised but stamina and the ability to cope with long stages in cold and wet weather in less suitable clothing must have been better. The Poulidor generation probably enjoyed enjoyed French cuisine more too.

More on that subject? Go here: http://www.bikeraceinfo.com/commentary/theobald-larry/Kite-men-lightweight%20riders.html

Nice work Mr. INRNG.

RIP Pou-Pou.

I’m not sure I follow your article entirely Larry, though fair play for writing it. My thinking is the same riders would excel if you switched them from era to era. Froome would still have been top dog in the 40’s, likewise Coppi now and Roglic in the 60’s and Poulidor in modern times. It’s just that if Roglic was riding for Mercier rather than Jumbo-Visma he’d have likely had farmers shoulders and a quiff haircut and Poulidor now would be forced to be 5-10kgs lighter than he is in those photos. Rik van Looy would still win classics today, he just wouldn’t have the light middleweights biceps. Anquetil looks like a modern rider I would say with his thin shoulders and arms, that must just have been natural though as he was known for his love of the high life. The reason the best are the best is because of their engine, not their muscles. It’s also worth noting as well that the contrast between a very thin cyclist and a normal person, particularly in Coppi’s time, would’ve been much less because everyone was thin then in the food restricted war years when most people had manual jobs. Coppi wasn’t competing against muscle bound actors for those house wives affections, and you could spend the entire 40s travelling around Italy looking for a fat person and probably not manage. I think EPO was the biggest factor allowing larger riders like Indurain and Riise be Grand Tour winners, and as recently as the turn of the century Richard Virenque was very much a housewives favourite.

Fair enough, I have zero problem with anyone who disagrees with my claims despite what I think is plenty of evidence to back them up. But you even admit Poulidor would need to be much lighter to compete today (unless you consider 5-10 kg not much weight in a world where people argue a minimum bike weight of 6.8 kg is draconian)

One thing’s for sure, I doubt any of these other folks would ever have been ski-jumpers before they took up cycling! 🙂

For some entirely none scientific research I put ‘Fausto Coppi’ into Google Images. It is noticeable that in photos of him riding the members of the crowd are as thin as he is, if not thinner. That was the way then. My point being that he, and other cyclists of his time, weren’t unusually skinny by the standards then and so could be seen as sex symbols like anyone else. Riders of the 50s, 60s and 70s were noticeably beefier, like van Steenbergen, Poulidor, Merckx, Moser etc as they filled a gap between the shortages of the war years and the advent of scientific coaches realising that watts per kilo were everything, which seems to have been pioneered by Conconi (and then Ferrari and Cecchini and eventually everyone else) who was known for liking to try out his findings on himself and was rake thin. I agree with you that current GC riders look unhealthily thin, and that small gears have closed the gap between climbers and rouluers on climbs. I’m not sure anything can be done about it though, a minimum weight would penalise tiny riders like a Tom Pidcock or a Paolo Bettini who would probably be required to put on weight to meet it and would not be able to compete. I suppose you could say that they have to use 53/39 11-23 for all UCI races.

What also seems to be a factor in the riders of the 50s-70s being beefier is that to make a living as racers, they had to do tremendous numbers of race days, in a wide variety of conditions. They didn’t just target on GT per year. I’m sure there was a decent appreciation that carrying less weight was an advantage in races with lots of climbing, but they couldn’t afford to target only those races.

We’re in an era where riders who target the grand tours can afford to shape their entire program, and their bodies, to those races. They’re surely more fragile for it, and they have to be hyper focused on this one thing, but such is the prestige of the grand tours over all other races.

Skijumpers are skinny because they are skijumpers. They are not skijumpers because they are skinny.

Having mentioned Poulidor found 42×24 for the Puy de Dôme one gear too much, it’s hard to imagine anyone racing up in a 42 chainring today. Poulidor put a minute into Merckx on the Mont du Chat using 44×23 and pedalling then was more forceful and required a stronger back/core; Poulidor used to chop wood with an axe over the winter saying it helped his back muscles.

When the Tour de France went over the Mont du Chat in 2017 39×28 or even compact 36×28 was more normal as the lowest gear and riders spin up at 85-90rpm.

I think this is the point. 42×24 on slopes like those of the Puy de Dôme is totally not imaginable today. You just have to see images of this era to realize that the pedalling was completely different.

Still in the 90’s, I remember it was the norm to use a 42 ring in the mountains.

Another great read Inrng, thank you.

I never realised how long his career was and when you mention the champions who he overlapped with – that’s really impressive.

He overlapped with Coppi too but never raced directly against him.

As for Bobet, Poulidor was an amateur but making a good living when he was invited to the Bol d’Or des Monédières race (the golden bowl) in his home region in 1956. He got in a late breakaway with Louison Bobet (Tour de France winner 1953,54,55) and pushed him all the way as the crowd cheered for “Pouliche”, his first nickname.

In those days the boundaries between pro and amateur were less structured than today and when Poulidor signed his first pro contract he took a pay cut because he’d be giving up all the prizes he’d collect on the local circuit.

A fitting tribute, Mr Inrng. Thank you.

One notable (and slightly off-topic) point about turning pro in those days, at least from a GB perspective, was that you also needed to be confident that you were going to make it as a pro.

I don’t know how it worked in France, but in the UK, leaving the amateur ranks was a one-way door as far as the federation were concerned. Once you became pro, there was absolutely no chance of racing again as an amateur, so if it didn’t work out for you, that was effectively your racing career over.

The GB federation provided no support for professionals, to the extent that they had to pay their own way to the World Champs, hence only the riders who thought they might be in with a chance of winning would attend. When Tommy Simpson won the rainbow stripes, he did so in a GB jersey borrowed from one of the GB amateur team members, because the federation didn’t bring any jerseys for the professionals. I know this because my dad was part of the amateur team that year and had to give up his race jersey into the jersey pool that the pros got to pick from.

Off-topic again, but it seems like as good a time as any to mention it: when you see Simpson on the podium and ‘Fat’ Albert Buerick is in the foreground, wearing a Great Britain cap – that cap was my dad’s. Albert wasn’t officially accredited as a member of staff and security wouldn’t let him into the presentation area. Dad had stayed with Albert’s family at Café Den Engel so the two knew each other, and my dad gave him the GB cap so he could pose as a member of the team and sneak into the finishing area.

His longevity as a professional rider marks him out as a special athlete, particularly given the era he covered when the age of 30 was often seen as the watershed between ‘prime’ and ‘past it’

One of life’s coincidences too that the year of his passing has seen the emergence of his grandson in the peloton.

RIP Raymond Poulidor and thank you Inrng and posters for the article.

Thank you for this. An admirable elegy for an admirable man. His human warmth always drew me to him. I had time to read this quickly last night, but saved it for the morning to give me more time to enjoy your writing. I suspected that this would not be one to read in a hurry, and I was right. You really are very good at this stuff!

Thanks, just sharing the stories he made. I could have covered ten times the things but it was getting long already; there are so many good stories in part because he lost and so there were more struggles than easy wins. Maybe over the winter we can return to a few anecdotes.

Make your posts as long as you like Mr Ring – we’ll read to the end.

Please, please do…

Always good to think of Poupou. It’ll always be.

Nice piece.

Made me think – we Brits think of us ourselves as being unusual in loving a valiant loser more than a winner, too. Is it something we have in common with our neighbours across the channel? Or maybe it’s actually human nature – we all find something more meaningful in people striving but failing (gracefully).

Interested to hear any of our American friends on whether it’s true there, in particular. I suppose the cliche is not…

Americans tend to love the comeback story above all others, both in sports and in life. Not so much lovable losers. They love to see winners, and love to see winners upset, and then they love to see those upset winners come back.

Hugely successful teams (Patriots, Cowboys back in the day, the Lakers, the Warriors) have large fan bases all over the country, and there’s also a big tendency towards fair-weather fans for the local teams (people with little underlying interest in a sport/team/individual, but become big fans as long as they win). LA was a good example of that in cycling in the US.

But losers, valiant or otherwise . . . not so much. Ask Billy Buckner. There’s a famous saying, incorrectly attributed to the legendary football coach Vince Lombardi – “Winning isn’t everything, it’s the only thing.”

I agree. I couldn’t think of a great sports loser loved by Americans. In fact NASCAR’s Dale Earnhardt Sr. is credited with the quote “Second Place is the First Loser”

OTOH, you are incorrect about the quote on “Winning isn’t everything” according to- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Winning_isn%27t_everything;_it%27s_the_only_thing

The obvious examples of the “lovable losers” in American sports would be the Red Sox and Chicago Cubs, though those ended their “loser” status this century. Buffalo Bills and the Minnesota Vikings, to a lesser extent as well.

In *individual* sports, Phil Mickelson was “the guy who always lost to Tiger Woods” for a long time, and got some popularity for that.

I also think Americans love the rank outsider “Cinderella” winner – the entire NCAA Tournament is based on this to an extent (Americans probably would have loved Walko’s victory, for instance).

@ Larry: I’m not sure what I was wrong about. I said it’s incorrectly attributed to Lombardi, which your link confirms. I went to UCLA, and knew a older gent who was an All American on Red Sanders 1949 team.

@SVH – yes, the Red Sox were/are beloved, but I mentioned Billy Buckner for a reason. When he misplayed that grounder in the ’86 World Series he learned how much the Boston fans liked being lovable losers. And in my childhood the Vikings and the Bills were treated with derision. They weren’t noble losers, they were chokers and the butt of many jokes.

KevinK – sorry, I should have written that you didn’t attribute the quote to the person who actually said it. Your post kind of suggests it was Billy Buckner.

A great champion and a great man, RIP!

I have an old Mercier bike (which is sadly rusting away) gifted to me by a friend. On its top tube there is a tag: “Pou-Pou ” and this prompted me to read about the man and I have to say I was touched. I must say that my dream bike as a child was a Mercier but after learning the story of Poulidor it was elevated to a legendary status.

P.S. I feel so guilty that I do not have the money or the time to restore my Mercier!

Unless the rust is bad, restoring an old steel bike isn’t terribly expensive. Go to bikeforums dot net and go to the C&V forum, post some photos of the bike, and you’ll get lots of free and expert help.

J’adore Poulidor !

Adieu Monsieur !

Look at his palmares. others have achieved more glory with less but sometimes it’s the value not the price. He raced against 2 x 5 time winners who were dominant in their sport. That classic picture encapsulates cycling and those two riders. Well written.

I still say “allez poupou!” when a cyclist goes by me. Must have shouted that thousands of times come to think of it. Living in the U.S.A. no one gets it. In France everyone knows…

In demeanor and general charm, the absolute antithesis to Lance — that’s how genuine he was.

Though I did hear from an old French pro that one of the reasons he did not win as many races as he could have, was that he was “cheap” ie, did not want to pay other riders to back off, which was (is?) often done in pro races. I wonder what you think of that last anecdote, inrng. Have you heard of it before? Obviously hard to ascertain…

It’s true, he could have bought more help in at times but would it have won the Tour? That’s harder to say, although on the Puy-de-Dôme in 1964 the likes of Jimenez and Bahamontes apparently wondered why Poulidor hadn’t approached them as they could have combined to work over Anquetil. One story is he’s in Tours-Versailles (Paris-Tours today, they ran it in reverse for a couple of years in the 70s) where he’s in the breakaway and on the finishing circuit his agent holds up two fingers to suggest paying two million francs (the old francs) in order to secure the result but Poulidor offers much less… and finishes second.

Thanks for the response inrng, I always wondered if what old Savelli’s told me was true… Fascinating, that other side of cycling. Other side for us spectators, but part and parcel of the whole for the ones in it… I wonder how much of that is still going on…

He appears to have had nous for money and holding on to them, slightly Scroogegy. Another anecdote – not to take anything from INRNG’s winter-writings – goes that he payed his hotel bills during training camps by playing cards with his team mates and winning.

OT:

I must say, INRNG, what a knowledge you have of these cycling’s history. I like to think that I know this, but your insight is really impressive. Poulidor’s first nickname, whoever knew of that. Add to this, who has ever used the word “bunkum”? I learned something new today, thanks.

OT: (On Topic!)

Over at VeloNews.com they have a piece on PouPou too, with an interesting take; the last of the black and white era of photography. More B/W-photos would have spiced the piece, but nevertheless, it is interesting.

An update to the story of Jiminez and Bahamontes, apparently they approached Poulidor’s team manager Magne the evening before to ask about being paid not to win the stage but Magne said no, so apparently it wasn’t Poulidor. Had Poulidor won the stage he’d have taken the race lead with the one minute time bonus. But that’s all part of the legend now, things conspired so he never did wear yellow and win the race.

Poulidor was not seen as a lovable, genuine charmer by his contemporaries either in the peloton or the cycling press. The general perception was of a curmudgeonly miser who couldn’t or wouldn’t get on with people.

The iconography of Poulidor started mainly with the non-cycling French public and non-cycling commentators like Blondin. They created an image of him which satisfied their needs and their desires. His great contribution was to realise this and play up to it for all he was worth especially in retirement, as shown in INRNG’s appreciation. This image has been taken up and regurgitated as received wisdom by cycling fans who never saw him race.

There is a contrast here with one of Pou-Pou’s chief rivals. A genuinely friendly world-class cyclist, loved and respected by his peers, adored by fans of cycling both then and now, Felice Gimondi died earlier this year. He was also a humble man from a humble background and a true champion. Gimondi hardly died unmourned, of course, but there was nothing like the weight and depth of eulogising as for Raymond and his pou-poulism.

Fascinating perspective, Anom.

Do you REALLY yell out something that your average American cyclist would translate as “Go poo-poo!”? I’d be afraid some of them would tell YOU where to go, or worse! 🙂

It was a lovely testament to his legacy in the French press (l’Equipe) that although he was the eternal second, Poulidor was the “Champion of the Heart”.

Thank you – another brilliant article.

Great tribute, thank you!

What a beautiful piece. I learned so much reading this. Thanks to INRNG for adding so much depth and perspective to the sport all readers of this blog love. Simply the best reporting and commentary there is.

RIP Raymond.

What a beautiful carreer, what beautiful charachter.

He still lives somewhere in his grandson (who does not often finish 2nd, btw…).

A beautiful story.

Excellent

Beautiful entry. Thanks, Inrng.