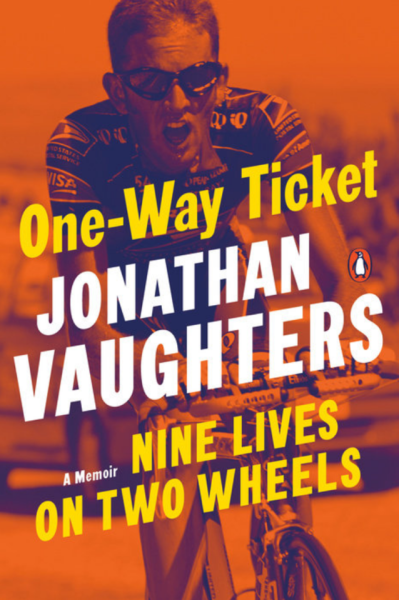

One Way Ticket: Nine Lives on Two Wheels by Jonathan Vaughters

Jonathan Vaughters has written an autobiography that covers his start in cycling, the rise up the ranks and his move into team management. I’d been looking forward to this book for some time as there few books from senior team managers, the only other contemporary one is from Marc Madiot.

We start with chronological account of a teenage racer rising up the ranks, the likes we’ve read before. There are a couple of moments when Vaughters steps back from recounting his adolescence to dwell something that would later repeat itself, whether exploring the grey areas of cycling’s unwritten rules, or exploring ethnocentrism – when as a junior, he and his peers believed foreigners could dope but their own wouldn’t – as well as a bad habit of “always leaving people behind” and these moments foreshadow future events. The first chapters are amusing while illustrating how different the US cycling scene was, as a junior he was hanging out in a bike shop run by hot-headed Italian expatriates, driving from state to state to take on senior riders and domestic pros in order to get noticed and score prize money and motorpacing behind his father’s old Volvo. Meanwhile peers in western Europe had it served on a platter with races on their doorstep and more.

Vaughters makes it to Europe with the US junior team, a golden generation with Bobby Julich, Lance Armstrong, George Hincapie, Chann McCrae and others but there’s no automatic route into the U23 scene and then a pro contract. He has to go via Venezuela to find a Spanish amateur team and literally buys a one way ticket. He lands at Madrid airport to meet his new squad…

“I was dressed in a tweed sports coat with a nice waistcoat underneath, which I think was the reason it took my pickup party some time to find me. He probably expected a jock, wearing a tracksuit and athletic shoes”

This is part of what makes Vaughters endearing, who else would sport tweed on a transatlantic flight? Where this fashion sense comes from isn’t obvious. Other eccentricities appear, such as his training regime where he works out that he needs more intervals and controlled efforts to boost power and ends up on a home trainer… mounted on the roof of the house he was staying in, for all the village to see. It’s quirky but determined, he wants to succeed and sets out on a path regardless of what friends or team mates think as his passion for the sport turns into work.

Meanwhile EPO is on the rise, as are rider haematocrit counts. Vaughters resists, then gives in. The story of going from refusal to rationalisation is better done in David Millar’s Racing Through The Dark or Thomas Dekker’s Descent thanks to more detail and you probably know the story too but for the general public and newcomers to the sport, the widespread use of EPO, and the lack of consequences, is something that needs context.

Vaughters tells of Lance Armstrong first as a junior, then as a Motorola rider and the Texan features more than anyone else in the book, more than friends and family, a lot of it with Vaughters trying to set the record straight post-USADA. It’s understandable given their paths crossed for years but means that there are moments where it’s less “one way ticket” and more “my version”. Did Vaughters bring down Armstrong? No but he surely was a catalyst. Floyd Landis got the ball rolling and Vaughters was there to corroborate stories in the media and underpin USADA’s work.

The final third is the more unique angle as it covers the creation of the Slipstream team and the difficulties keeping it on the road. Given the repeat problems of sponsor retention, the team almost disappearing and more there are probably more stories to tell than, say, Marc Sergeant explaining how Lotto-Soudal have enjoyed stable funding for decades. There are many rider autobiographies but few from the perspective of the team car or service course office, especially contemporary ones. There’s a mix of calling the shots from the team car, like Johan Vansummeren’s 2011 Paris-Roubaix win and the business of pro cycling such as trying to keep the team funded. Here Slipstream co-founder Doug Ellis’s involvement with the team, both as a mentor and a generous benefactor, stands out. Roger Legeay gets several creditable mentions too. There’s more setting the record straight on issues with British riders David Millar and Bradley Wiggins, with Millar it’s about leadership of the team, with Wiggins it’s less personal and more a clash with Team Sky and their prodigious resources. Vaughters covers his time as President of the AIGCP, the association of pro teams, and his work on the revenue-sharing pact with RCS… but curiously there’s not one mention of the Velon group which has perpetuated this. There’s more bemoaning pro cycling’s sponsorship model but only a few pages ago the same model let Vaughters into the sport, bootstrapping a junior development team into the pro ranks and, with the benefaction of ASO, ride the Tour de France all within the space of a few years. Thankfully the book doesn’t turn into an economics lecture and if anything this section skims and skips a lot to the point where major events in the team’s course don’t feature. Yake Ryder Hesjedal’s Giro win where there’s only the most oblique mention as Vaughters writes “a few days after Ryder Hesjedal won the 2012 Giro for our team”… he was in talks to then Giro boss Michele Acquarone about the revenue sharing deal. Vaughters has led a rich life so there’s plenty that can’t fit into 380 pages but a grand tour? In fact there are many big stories that don’t feature.

It’s an autobiography but sticks largely to cycling, there’s little on personal tastes from clothing, music, fishing, wine or that he’s got a private pilot’s licence, all of which ought to make him more interesting. At one point there’s a mention of his wife Ashley when only a few pages before he was married to Alisa; it’s only later there’s a chapter dealing with private life covering marriages, divorce and more. Here things get a lot more personal, it must have been the hardest part to write and no fun to print for public consumption which might explain why it’s tackled last.

The Verdict

Enjoyable to read, unsatisfying to finish. An easy read even if there’s a gear change from wild west era anecdotes that cover junior racing, burritos, Spanish EPO and buried bikes and then to UCI politics and the finances of a pro team. The early part is fun and light-hearted before turning darker as the racing gets more serious; the latter part makes Vaughters’ perspective as a team owner more interesting. I’d been looking forward to reading this, yet once done there’s a feeling of something missing. Closing the book on the last page is like getting out of one of those old train compartments where you’ve shared a long journey with a fellow passenger and they’ve told you plenty of stories but you never got the measure of them as person. Once you finish the book you realise many material incidents from Vaughters’ time are omitted making for an autobiography that feels incomplete and the tone doesn’t quite capture the humour and quirkiness of Vaughters.

- One Way Ticket will published as paperback by Penguin Random House in the US during August and Quercus Books have already published a hardback version with the paperback to follow

- Note: a digital copy of this book was made available for free for review

More books at inrng.com/books

Are books like these EVER worth the read? The guy’s only 46 for Pietro’s sake! Perhaps when he’s retired he can tell a more complete, balanced and interesting story? There was a time I sort of admired what the guy was trying to do in cycling as manager/team owner but since he’s become Mr. MBA and involved with Velon it seems all he cares about is somehow turning his team into a franchise worth a fortune…at ASO’s expense.

His DS Wegelius has a good book, it’s more about being a gregario but worth reading. Madiot’s is a good read too. Like I suggested above, I put it down thinking “hang on, what about…” and the personality doesn’t seem to come across but it’s still an enjoyable, easy read. Just feel it could have been more.

I thought that one was OK but it’s like they oughta sell ’em for half price since the story’s only been half written?

Eh, not every part of a life is equally interesting. Sometimes it’s good for the story to be written when the writer can still remember the bits that are worth writing about.

I have no issue with the stuff being written down when the guy can still remember it, but that doesn’t mean it has to be printed and sold, does it? Seems it could wait until the man’s career in cycling is completed and he has the benefit of perspective he might gain over the next decade or two? I admitted to not being a fan of this guy, but there are other bio books I’ve skipped for the same reason – they’re a few decades too early.

Yes, Wegelius’ book is excellent, one of the best sport autobiographies I have read.

Wegelius’s book was interesting but I felt he skipped over a lot of stuff related to doping. He rode with Mapei then Danilo Di Luca but his insights into this area of cycling felt really sparse, as I recall. I realise he still works in the sport and has confidences to respect but it made for a really frustrating read.

PS – I recently read Fignon’s book on INRNG’s recommendation and thought that was probably the best cycling autobiography I’ve read, aside from Kimmage’s Rough Ride. Couldn’t say I warmed to Fignon at all, but he was a pretty fascinating character.

Nonsense, The Secret Race, Domestique, even the Descent offered fantastic insight into the inner workings of the peloton. Some of us really like the inside baseball of the sport, stories of guys who almost have a 6th sense of when it will rain or when to escort their leaders up to the front. These aren’t accountants; where most people are really starting the interesting part of their careers and finding the roles they’ll build their professional working lives around (low to mid 30s) these riders are retiring.

The Secret Race was brilliant actually, I forgot about that, although I was slightly queasy about giving Tyler Hamilton money. Cycling fans have to hold their nose sometimes…

Wegelius’ book is a great read especially as he’s not a champion etc.

Thanks for the review, do find Vaughters very interesting to listen to when interviewed or giving his opinion.

Small typo at end of first section should be stories not stores

Might also be woth reading Phil Gaimon’s ‘Draft Animals’ for the perspective of a rider on Vaughters’ team, a rider who doesn’t feel he was treated all that straightly…

Anonymous ? Twas me, forgot to fill-in the name field ;o)

I enjoyed both of Phil Gaimon’s books. Agreed, that Vaughters’ doesn’t come across as the total straight shooter in the 2nd book!

He acknowledges in the book this aspect where he can let people down, it’s one of the parts where he notices a tendency towards this early on and it signals more to come, or perhaps those of us who know more of the story know more is to come. Without a spoiler the book does attempt to explain part of this, it’s not necessarily selfishness.

JV is in it for himself all the way. That has never been a secret.

+1 on that. I wonder if Vaughters explains in the book why he is still even in this sport given he said he’d leave it if any of his riders ever got caught doping? You’ll have to let me know as I wouldn’t even use his book for toilet paper myself. I see no reason to read yet more self-serving tripe from a guy who exists merely to big up himself. Every time EF have a chance to win something I hope they don’t entirely because of this guy.

Read the book and he suggests he’s lost a marriage because he was too stressed by sponsor hunting. But one other omission is the Danielson case. The “I’d stop the team if someone tested positive” statement was foolish to have made in the first place, dumping the entire squad because of Danielson or anyone else wouldn’t make sense.

Another book by a senior team manager (sort of) is Rod Ellingworth’s Project Rainbow

I felt that a lot was either skimmed over or too raw to really tackle in depth. I like JV but it felt as if this was him saying “I’m human, this is what I’m like” rather than providing a history of US Postal, Slipstream etc. There’s a lot to tell, but this isn’t the book to do it.

I’d tend to agree but there wasn’t too much of the “this is what I’m like” either, nothing about clothing tastes, wine, the pilot’s licence etc etc

No, but there was the diagnosis with Aspergers, which seems to have come as a bit of a lightbulb moment for him and informs quite a bit of the book.

Being such a high profile and open figure we probably know a lot about him and his story, which makes the omissions stand out more.

I started following pro cycling because of a documentary I stumbled called Blood Sweat & Gears which was my introduction to Slipstream and Vaughters, so I’ll give it a read.

Okay, it’s on YouTube. It makes me feel quite naive.

https://m.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL9Liffw8CgFxPR7szi7gRuae6e6VjKQ3z

> Vaughters has led a rich life so there’s plenty that can’t fit into 380 pages but no grand tour? In fact there are many big stories that don’t feature.

Maybe these parts are best interpreted as being the parts where there is still more information to develop from the current official version of events.

The dog that didn’t bark in my book because …………….

Vaughters probably has a habit of leaving people behind but he surely also has a habit of simply not liking certain people very much. Certainly the case with Hushovd, perhaps the case with Hesjedal also and hence the ‘silent treatment’? In any case he is an interesting character with many stories to tell – from what I’ve read in the reviews his view on the 2011 Roubaix is one to look forward to.

“… he was talks to then Giro boss Michele Acquarone about a revenue sharing deal”

-> …he has talks?

He always struck me as being this righteous DS, overplaying the fact that he is a “pentito” on a crusade to make cycling great again. Doesn’t do it for me.

But I appreciate the fact that his team is still around, knowing how hard it is to stay above water in this sport.

Reading your review of Marc Madiot reminded me of the TV interview held by Pinot and Madiot on the rest day.

Pinot’s body language suggested a significant rift with his boss. It seems he hadn’t managed to “stir up the riders guts” with his pep talks, but I hope we haven’t seen the best of Pinot in this tour yet. He has a lot to offer.

Isn’t Vaughter’s autistic (or at least has a form of Asperger’s)? This is likely to colour the way he feels and represents certain aspects of his life and the way he handles relationships and to this end it sounds like this comes across in the book in a subversive manner.

This is something he touches on at the end and does help explain things you’ve read earlier.

There’s just something about JV that I don’t like! To me he just comes across like a silicon valley CEO trying to “monetize” everything!