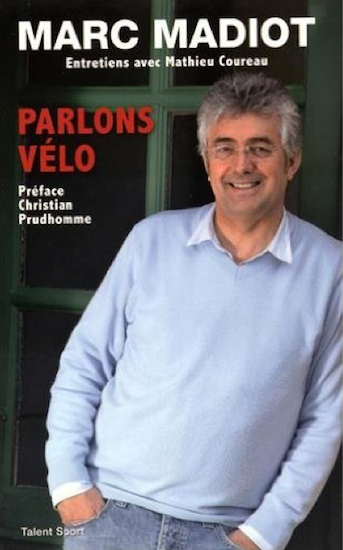

Parlons Vélo by Marc Madiot and Mathieu Coureau

It’s written in French so at first sight a book review may not be of great use to an anglophone audience but it’s a hook to write about Marc Madiot, share some legendary anecdotes and show some hidden sides to one of the sport’s bigger personalities.

Often seen as a hothead and a relic from the past there’s the story of a manager who, while Russian billionaires come and go, has lead one of the sport’s longest lasting teams and sponsorship deals.

“Cycling is 98% suffering and 2% pleasure“

The tale starts as you’d expect, Madiot is a country boy who grows up on a farm and cycles instead of taking the school bus. He grows up impressed by the work ethic of farmers, especially his father’s stance of only doing a job if you can commit to doing it well. Rurality is central to French cycling, the Tour de France and other races connect places that simply are not on the Parisian radar. Yet Madiot has a flamboyant touch, as much as he admires peasant hard graft he always wanted to look the part on the bike, a Velominati before his time. Back in the days a pro would only get team issue shorts and a jersey and Madiot wanted to look classy so he drove to the Italian border off to buy a bulk order of white socks and gloves to look the part and throughout his career he insisted on a clean bike and spotless kit. It’s why FDJ use white bar tape today and why when they have the French champion the jersey has no logos.

The Power of Speech

When Marc Madiot was a junior he attended a training camp for promising riders held on the Vercors plateau, a remote area near the Alps where the best would be selected for the national team. The selector told the riders to get on their bikes and he’d announce his list. They ride and are told to stop and sit down in the grass where instead of being told the selection the coach gives an hour long talk about the resistance fighters in the Vercors and then, in five minutes, names the riders selected for the team time trial which included Madiot. What mattered to the coach was pride, inspiration and culture rather than reading a list. This made an impression that’s lasted ever since with Madiot as a patriot and a motivational speaker known for rousing orations in team briefings designed, in his own words, to “stir up their guts”.

This is the side we often see of Marc Madiot, if you haven’t heard a team briefing then you’ll have seen the man leaning out of the team car screaming at his riders or the video of him screaming like a maniac into race radio, crying on TV when things have gone wrong or railing at the commissaires. He’s hot headed, passionate and almost unhinged.

Like Ocaña, Copy Guimard

Yet this book reveals a different side and another mentality. Luis Ocaña was Madiot’s hero because of his passionate style and attacking nature. After winning Paris-Roubaix for the second time, Madiot’s fan club decided to invite a surprise guest to celebrate and the curtain is pulled back to reveal Ocaña, “my idol was in my house“. They say never meet you heroes but Madiot is delighted to see Ocaña, they drink champagne on a sofa. Madiot has kept the sofa ever since and will never get rid of it in the same way a starstruck teenage might refuse to wash their hands for days after meeting their idol. Later Madiot met Eddy Merckx over dinner and said “you’re the guy I used to hate the most” because of the way he’d thwart Ocaña time after time. A laconic Merckx replied “I understand” and the pair enjoyed a good dinner. So Madiot isn’t just an Ocaña fan, he keeps sofas he once sat on and hated Merckx. So far, so passionate. Yet he rode for Cyrille Guimard’s Renault team. Guimard could well be the greatest ever directeur sportif and he certainly made an impression on Madiot who learned about saving energy, bluffing, calculating, tactics and technology. Guimard simply didn’t do rousing speeches and Madiot says he’s tried to copy as much as possible when it comes to running a pro team.

There’s a long section on the fallout of the Festina affair where essentially there was a pact between the sponsor FDJ and the team: ride clean and we’ll keep sponsoring. It worked because they were French and guaranteed a start in the Tour de France by virtue of having some of the best French riders. It meant a change, out went the foreign hired guns like Davide Rebellin, Max Sciandri and Mauro Gianetti and the team became more visibly French but less ambitious to the point where Madiot tells EPO was so out of control that they had to retreat from even trying to be competitive in some fields and to find pleasure in more modest goals: winning the Etoile de Bessèges instead of the Tour. Yet for all the franco-français aspect of the team Madiot signed neo-pros like Bradley McGee, Baden Cooke, Thomas Löfkvist, Philippe Gilbert and Bradley Wiggins, for someone said to be wary of les anglosaxons he’s certainly helped plenty of them. He even tried to hire Floyd Landis at one point but when he and his brother Yvon told Landis and his manager that FDJ didn’t have a doping programme and that they wanted to see Landis’s medical file the Americans never called back.

As a rider Madiot seemed strong-willed and managed to win Paris-Roubaix twice making it his preferred race ever since. He himself describes a “pseudo-racer” phase as he became a manager, he kept seeing himself in the saddle instead of his new place in the team car and office. It’s said this is detrimental, that Madiot suffers from the empiricism of ex-riders who won races in the past thanks certain habits and routines and think that since they won this way if others copy the process they will win too. There’s a superstitious streak too, the death of Madiot father’s leaves him distraught and convinced that his spectral presence helped Arthur Vichot to win the French championships, another race dear to Madiot because of its symbolism and because he won it himself. The book even explores Madiot’s religion, a rare if not very private topic in the peloton.

From Patron to Chairman

Madiot is the face of FDJ but increasingly a delegator. It started out with his brother Yvon, an ex-pro, who helps with recruitment but today the performance element is handled by sports scientist Frédéric Grappe who manages a roster of several coaches and support staff including Julien Pinot, elder brother of Thibaut. When Madiot gives his résistance speech it’s the Grappe and Pinot who have to remind the riders to sit tight in the peloton, watch their watts and save energy for the finale.

Conservatisme

There’s a big conservative streak. Madiot is President of the French professional cycling group the Ligue Nationale de Cyclisme and with this hat on he’s a defender of French cycling. He says he’s not against new races on the calendar but that it has to be done cleverly and to take the public along for the ride; witness the lack of crowds for the Tour of Beijing he says. He’s even sceptical of ASO at times for their cool business model.

“Marc is Marc“

It’s not in the book but the phrase appears elsewhere from time to time, as if to excuse his eccentricities. Yet this has to be part of the appeal, the charisma. Arthur Vichot calls Madiot an “actor” and it’s a compliment that shows Madiot’s ability to deliver a speech or play a required role.

The Verdict: an entertaining read that shows complexity to a personality that can appear simplistic in caricature. Madiot’s passion for the sport is worth celebrating, it underpins his longevity. Read the book if you can; if not then celebrate the man.

It leaves the impression of someone hard to classify. Madiot is the patriot who plays La Marseillaise on the team bus yet is equally proud to have given McGee, Wiggins and Gilbert their first contract as he is in signing Thibaut Pinot. Madiot decries the increasing use of English in cycling officialdom instead of French, rails against Velon and mocks former team mate Greg LeMond’s apparent addiction to Coca Cola yet lives his own American dream with a Corvette in the garage and sports cowboy boots for six months of the year. Madiot decries race radios yet screams motivation into the mouthpiece; he loves Ocaña yet wants to copy Guimard.

The book is a question and answer session rather than a biography. There are nine chapters each with their own themes and they proceed like interviews with Coureau posing a question and Madiot holding forth but it goes much further than a magazine interview, at close to 250 pages there’s space to delve into more subjects, to follow-up and to think. Parlons Vélo works well as a book but “an evening with Marc Madiot” could and should be a sell out in Parsian or provincial theatre.

- Parlons Vélo is published by Talent Sport and available as a paperback and an Amazon e-book

A list of prevous book reviews can be found at inrng.com/books

Excellent recap for us less proficient in French.

Thanx, Inrng.

Thanks for sharing as there’s no way I’d ever read this unless translated into English, which I’d guess is doubtful. Pro cycling needs more characters like Marc Madiot and less like Oleg Tinkoff.

Agreed. Now how can we get the sport to a point where Madiot’s team is just as competitive with the big teams?

Make a fortune, and give €20m of it to FDJ every year..? 😉

That could work but it’s not want they want for now. It’s in the book and been said before that they don’t buy in big names, the plan is all about trying to recruit some of the best young riders and develop them from neo-pros into winners. So far if they hire riders it’s to fill small gaps, eg Kevin Reza to help in the lead outs, Steve Morabito for stage race domestique work etc.

Thanks much for that, finally again a cycling book worth reading after the Millars, Wiggins etc. I won’t make the same mistake as I did with Fignon’s book (reading the English version should it ever be published) and immediately downloaded it in French.

http://photos.grahamwatson.com/Print-Gallery/Marc-Madiot/i-72cx3xG/0/M/Madiot-M.jpg

There’s endless coverage of anyone who speaks English but little of those who don’t. We get whole books, website interviews, podcasts and more for Jonathan Vaughters, Rod Ellingworth, Dave Brailsford, Sean Yates, Charlie Wegelius but there’s nothing on Marc Madiot, Patrick Lefevere, Eusebio Unzue and others who are surely more important to the sport.

Well here is the book on Madiot and some readers might remember his (ghost written) blog on cyclingnews.com in English during the Tour de France. You do touch on something though, it’s hard to know if it’s supply or demand which explains the wealth of media covering English-speaking cycling.

Good point Anton – we get so much coverage purely on the Anglo team executives on Velonews, Cyclingnews, etc. but we never really get the story from Patrick Lefevre, Madiot, Unzue, etc. But arguably, Lefevre et al. are more relevant to the actual sport.

And, even if you’re just looking at success, Lefevre’s had one of the top Classic teams in history.

Would be interesting to hear Lefevre’s story too.

Follow the belgian cycling media and you will soon get tired of Lefevre’s opinion

Quite.

Same goes for Italian and Spanish media. Everyone’s got sort of a national focus.

I guess there’s also a matter of access and proximity – or of having the chance to foster those personal/professional relationships which journalism is heavily fed on.

What I always found impressive (and I posted some data here) is the huge amount of Italian books about cycling, considering that Italian as a tongue hasn’t got by far the same potential market as English or Spanish.

This

If you’re interested in news (in English) about more than just UK/US/AUS, to do with smaller teams, and a multitude of race previews, CyclingQuotes.com is miles better than cyclingnews.

I’ve assumed that the French, Dutch/Flemish, Italian and Spanish-language media was just as full of coverage of riders, DSs and event organisers who speak those languages as the English-language media is of Anglophones. Simply because it’s easier to interview somebody whose first language is the same as yours. And I also assumed that I just happened to notice the English-language stuff more, as I don’t regularly follow media that I can’t understand.

You’ve got a talent for assumptions, Nick. I grant you that I can fact-check a good deal of your assumptions, and they tend to prove true! 😀

Thank you for that. He is the real deal. Personifying that essence we love so much in this sport.

Thanks for bringing this up. A side of the sport that many of us anglosaxons should really get to know.

Pre-Lemond, the French/Italian cycling romanticism was the essence personified of California road racing.

Still love the look of cloth white tape on a steel bike!

Viva La France.

It sounds an interesting read, and he seems a fascinating character.

I wonder if even Madiot is succumbing to ‘modern’ cycling however, given his team’s self-assertion to win the Tour in the “mid-term”, or has he delegated these aspects to Frederic Grappe et al?

To tie in with the recent article on lightweight bikes – Pinot took the Alpe d’Huez stage this year on Lapierre’s 2016 Xelius SL ; a lightweight climber that can come in well under 6kg, were it not weighted down.

Food for thought?

The team have had a few issues with the bikes in the past. It’s said they requested an aero frame and a lightweight model, it’s all part of the team’s push for performance with Fred Grappe becoming increasingly influential.

I love the Ocana story! It makes him into such an empathetic character. I’d do the same thing and it’s also why I love hearing interviews with Wiggins (especially in the non-cycling press) when he talks about his heroes and aspirations.

Wiggins did a great interview with Bahamontes here in Belgium where the fact that the Sky press guys probably never read it let him go a bit off message.

I’m a bit skeptical about “Saul-to-Paul” Madiot and his conversion on the road from Française de Jeux to FDJ through the hardships for France due to the Festina affair.

What’s sure is that things didn’t go exactly as reported by inrng above.

At least two out three names of compromised “foreign hired guns” can’t be related at all to any sort of “cleaning up of the team”… Rebellin went away the year before (and I don’t know if and when did he pass to the dark side, but in 1995-1996 he was probably riding next to clean, according to the trustworthy Sandro Donati – and he was writing to Verbrugge asking for blood tests! Poor soul). Sciandri stayed one year more, racing another full season with Madiot after the Festina scandal. At most, it was Gianetti that they sent away. Nice.

Heavy doping (EPO and other hormones) was going on in the team and it was mainly homemade, French recipe with some Belgian help. Morelle, Jan, Menthéour…

But, OK, we must believe that after Festina the sponsor said “enough” and they went clean – what a pity that those fine young French went on doping well into the 2000s, like Ledanois, Magnien.

Wait wait, but it was the mischievous riders’ fault (as always)!

Was that so? Didn’t they suspect anything about Hoj when they hired him directly from USPS in 2000? Were foreign guns fine again? Why hire in 2001 a well-known doper like Durand? French hence fine?

In 2005 they were cherry-picking Bartalucci, involved less than 4 years before in the Sanremo blitz, under investigation by the Italian justice. I don’t want to enter in a debate about Bartolucci, but, hey, it was all over the press, why did they need to hire him? I guess you know the guy ’cause he was in the 2011-2012 Team Sky, along with Leinders (speaking of cherry-picking).

Nevertheless, I’m happy to acknowledge that in the last 8-9 years there were less worrying signals, just borderline situations like Duval’s or Offredo’s, or even the Delage story (low cortisol, blamed an inhaler, since no cortisone was found in his system he was “acquitted” – very much Unzue-style). I agree that this cases might be clues… as well as lack any relevant meaning.

Probably not the healthier place in the world, but I’ll admit that it shouldn’t be a doping den, either. They’re probably the only French team who tried to live up to the faux mythe of a clean(er) national cyclism, whereas Cofidis, Credit Agricole and Ag2R all had enough doping scandals to make Astana pale 😛 (and Europcar have been long walking the line).

Yet, it’s kind of sad that they’re trying to sell out a twenty years long narrative which wasn’t simply there. I guess it’s Madiot’s style. Tell the story again in a most pleasant fashion. I’ve read elsewhere (but it may just be an urban legend) that his personal admission was something like: “Yes, I was doping, but just for criteria, never for a real race”. A bit à la Basso. Or, if you prefer, the eternal: “yes, it was me smoking… but not inhaling!”.

I’m sorry… did you say that when Rebellin left FDJ he was riding clean?!? What?!?

Rebellin was an example of clean riding in 1995 and maybe (not very sure) in 1996, too. I don’t know about 1997, when he raced with Madiot, but since Français de Jeux was a heavy team doping team at the time, he might have learnt a thing or two. However, this is wild guessing, whereas the first sentence above has got a reliable source (who maybe was wrong… but no reason has surfaced in the while to think that).

I have serious doubts Rebellin was clean in before 1997:

For example (keep in mind this isn’t proof, but I’m addressing your statement that he was clean pre-1997):

1. 1994 Amstel Gold Race: Rebellin finished 5th, beating admitted dopers Chiappucci, Didier Rous, Virenque, Steven Rooks

2. 1996 Giro: Rebellin finished 6th on GC, ahead of Festina’s leader Robin, Evgeni Berzin, etc.

3. 1995 Milan San Remo: Rebellin finshed 4th in a 250+km race against many guys on EPO, but he raced this clean? C’mon, you can’t believe that. This race was won by Laurent Jalabert, definitely was using EPO.

Gabriele, your posts are very interesting, but I’m sorry to say you’re trying to put holes in Madiot’s story with a story that has many holes itself, and this is only the first paragraph!

http://ricerca.repubblica.it/repubblica/archivio/repubblica/1996/11/01/rebellin-ultimo-dei-puri.html

November 1996. Have a look to who Donati is and has been (think they’ve got his profile at WADA). He’s a pretty reliable source. And the article was written by Eugenio Capodacqua alias Torquemada, one of the most doping-obsessed (for good or ill) Italian journalists.

Results can tell whatever you want, especially if you haven’t see those races (so haven’t I, in this case).

And if you use the results that badly, they end up meaning nothing.

Rebellin is beyond any doubt – doped or not – a superior-level one day rider. How could it possibly make sense to match his results in a Classic with riders who were barely decent as one-day riders? Rooks was the most acceptable one you name, but he was on the verge of retiring, I don’t even know if he stopped that year or the following one, but he then struggled to make a top-ten! Come on! And the Sanremo… well, it’s not exactly a selective race.

Many things might also be said about the 1996 Giro and the judicial pressure on it.

However, it’s worth noting that all the decent GC riders who were actually fighting for that Giro arrived well above Rebellin, occupying the first 5 spots with a time difference of about six minutes and over. Faustini, Shefer, Robin… what’s their level? And what about the curve of Berzin’s career? Have a look at that. He was a case of frequent Be-tancu-rzin’.

Yours looks like a case of crazy “magical doping thinking”. “Doping can whatever, no clean rider will ever ever ever beat a doper, irrepsective of their capacity”. But I suppose you can go and find some race in which, dunno, Moncoutié has beaten some known dopers, can’t you?

All that said, I’ve been quoting a source which I consider pretty reliable, but I personally wasn’t there, hence maybe the source was wrong, or his data were outdated (Donati was already working on his famous report as soon as 1994), or both the journalist and the scientist confirmed something they had discovered without noticing things were at changin’. All in all, with all its (huge) limits, that’s sort of “historical knowledge”, while fishing in the results and going into wacky-inference mode is wild guessing at best. Speaking of holes.

Even more important, that wasn’t even the big point. Rebellin went away one year before than Festina’s scandals, so how could any relation exist with the “FDJ asked us bla bla bla” story? Rebellin was already far away when the team (and apparently Madiot himself) were going EPO wild during the 1998 Tour. Which means that even if Rebellin himself (or a funny user who might decide to post as “Davide” or “Rebellin”) came here saying he was full of EPO all the way long, well, great, but that wouldn’t change anything regarding the “problems” I’ve underlined in the FDJ national-spiritual conversion narrative.

Haha, I agree, my “inference mode” is based on my instincts and analysis (didn’t I say “keep in mind this isn’t proof”?? haha).

But, back to Madiot, I do get your point though, and it seems as if Madiot’s quotes might have some dates mixed up. Madiot could be painting the past with rose coloured glasses, but as you mentioned, it does appear that FDJ cleaned up its act (for the most part) quite awhile back. I’d say, at least as early as the 2003 TdF. That was the year Baden Cooke won the Green Jersey, and Brad McGee won the prologue. Earlier that year McGee won the TT at the Tour de Suisse, probably a shorter TT than the Tour’s 2 TT’s in 2003, but McGee didn’t factor into those time trials. I wonder how McGee could have done if everyone else was clean?

@DMC

“Haven’t you seen the dopers he beat? He just couldn’t be clean!!!” 😛 😛 😛

Jokes apart, he apparently had a very good engine but, sadly enough, we’ll never know if he had all the rest which is needed to do great (I’m not only speaking of skills but, don’t know, physical health and the likes).

I’d tend to move the dates you suggest a couple of years later (always referring to “cleaning up” as a relative process), but it really doesn’t matter so much and evidence is more feeble and open to debate, too. The McGee thing remains anecdotic since he was staying on the team, and racing important races, also before, when the doping times weren’t over yet, which means he could keep safe its place and its decisions whatever the general attitude of the team.

Gabriele, did you actually read the book, did you actually read what Madiot said? Or are you only referring to the one sentence in this book review that says foreign hired guns LIKE Rebellin, Gianetti etc. were mostly a thing of the past after Festina (probably as fast or slow as contracts allowed it anyway)?

In general, I am not so sure it is really helpful to use a book review to form firm opinions about a very specific thing written in a book, if you haven’t read the book? If you did read it, ok, then it is of course something different (I bought it a few weeks ago, but my french makes it a very slow reading process. I really like it and will surely continue reading it. Very slow, but steady-even more so after this beautiful review).

I like your comments, always read them. And of course I also get what you mean in principle with the french clean narrative (although it doesn’t upset me that much-others have other narratives). But if you haven’t read the book, I personally just don’t think it is of any service or use to extrapolate that much and in this categorical form an opinion about a book from half a sentence in a book review. Even more so, as the review with no word mentions that one of those three named riders doped at that specific time. All it really says, is that after Festina the teamconcept changed: less ambitions, more french riders and a path – enforced by the sponsor – to stop the doping on the team.

hey Anon – don’t put them off! – I’m really enjoying this discussion between two folks who know way more than I do about this stuff…

No, that’s the last thing I want! I really enjoy Gabriele’s comments and knowledge. His comments are the only comments I always read. And because I do appreciate them, I wrote this. I honestly think it isn’t helpful this way and indeed a disservice he does himself (I noticed a similar thing happened before with the book review about the last Pantani-book”Debunking…”. I too was critical of that book, but I had read it and knew, what was in it and what not). That was all.

Anon, that’s a welcome observation, although if I read the book I’d go straight against the critics’ golden rule “you don’t need to see the movie to reach out for the rotten tomatoes” 😉

Jokes apart, you’ll concede me that I added the clause “as reported by inrng above” when I started writing – and we can comment on inrng’s version of the book, I suppose.

Yet, I’ll admit that as I went on writing I ended up assuming that the book review corresponded more or less to the book, until I finally attributed to Madiot and his team the whole narrative. And that’s not good, or it’s at least confusing. Perhaps that happened because I’ve got the vague feeling (far from a specific memory) of having been supplied the same tale about FDJ through other sources before – but I could be wrong.

I think I’ve been fair with FDJ, among other things they’ve got – and they had in previous years – several riders whom I appreciate quite a lot, just as I appreciate many things about the team racing style, aesthetics and so on.

What I don’t like about “the narrative” is not its story-telling aspect, but its architecture: things get connected, when you narrate them, while at the same time your casting the limelight on something may mean pushing something else in the shadows of oblivion. For example, the strong French component of their EPO rampage moment, or the doping cases they had with their French riders in the first part of the 2000s. Or the (Italian) doctor thing.

It’s not a nationalistic thing: if we assume that the tale really goes more or less like that (you’ll tell me when you’ll get there in the book), this way Madiot and the team WOULD be distancing themselves from the doping, just as *he did* with his personal experience of doping as a rider.

If you’re a regular reader, you’ll know that I’m not the biggest fan of the “repentant / unrepentant doper” logic. I don’t care about Madiot’s true feelings, or, better said, I believe he’s got the right to keep them for himself. I’m worried about a false more general image about how doping worked, which makes the fascinating narrative become an – albeit indirect? – source of prejudice or wrong assumptions.

People who read the book will know if this narrative is indeed in the book or not. I really don’t think that people who would have read the book will restrain themselves because of my comment.

Anyway, if all we have is what inrng hints at, I think that the blog’s readers might be interested in set that against a different perspective. This blog’s public is intelligent enough to form his own opinion, and doesn’t withdraw from questioning other commenters’ opinions, as DMC did.

PS The rotten tomatoes thing was a general joke, I didn’t think for a moment that this book would deserve them!, it’s probably good.

Thanks – I really enjoyed this piece.

Whatever may have been the case pre-Festina, Madiot does deserve some credit for giving a relatively safe haven to, and nurturing the nascient young talents of, McGee, Wiggins and Gilbert. McGee certainly credits FDJ and the French system for helping him to stay on the right path. I found his article in the link below pretty compelling on a number of topics. Hope readers find it interesting if they haven’t seen it before in the northern hemisphere.

http://www.smh.com.au/sport/cycling/how-dopers-stole-the-best-years-of-my-career-20121026-28aif.html

Interesting piece, I think I read it awhile ago. He’s a bit confused when rule #3 is considered – how could he work for this team when “Mr. 60%” was at the helm? Or did I miss something?

Fair comment Larry. I think he felt that Bjarne turned over a new leaf as a team owner and was one of the first to introduce an internal style of bio-passport. I’m sure plenty here don’t believe that CSC was “clean” but McGee felt that by the time it had evolved into Saxo – and he was a DS – it was on a better path. I have no idea whether that’s true but I have yet to meet anyone in cycling who doubts Brad’s bona fides (and considering the era he lived through, that’s pretty remarkable).

Riis introduced the “internal” program in 2006, I think (I could be wrong, I didn’t check), hence it means nothing in terms of no-doping attitude, given that we’ve got reports of team doping going on in CSC and CSC-Saxo beyond that year – again, more than just “opinions” and “feelings”.

It sounds a bit like what a Spanish doctor did (the man worked with some Saxo athlete in 2009, I think): his wife worked in an antidoping lab, and he used to have samples tested to be sure that his “treatment” was invisible for the tests.

And it wasn’t just about Riis: Andersen and Michaelsen had an hell of a past, too.

There are less proofs from 2010 on, indeed, but McGee was in as a rider since 2008, then was working with those types for a year or two at least. And then came the Contador & Pepe Martí phase, whatever you might think of that.

That said, I’m not hinting at any involvement by McGee. In that team, riders could apparently say “no” (which might mean “I’ll do it my way”), even if there was a notable pressure, especially on the captains.

And I totally believe that a guy could go on working in his straight way as a DS even in a rotten context.

We know for sure that FDJ *was* a rotten context along the first two or three years – to say the least – of his career there, but it looks like it didn’t prevent him from passing through that clean.

Sure, as Larry points out, all that makes rule #3 sound strange, but perhaps it’s sort of a utopian thing, something you should tend to, even if reality may force you to accept compromise (not about what you do, about the people around you). And in a press article which is supposed to enforce some no-doping mentality, the shades of gray wouldn’t just work.

religion, rare if not a very private topic in the peloton.

Why do you think this is the case? In America religion permeates many sports, basketball, baseball, football, golf, etc.. I wonder why it is so different with European cycling. Is it simply the case that Europe is supposedly more secular? Has there been any research or analysis of religion and cycling? Do cycling teams or races have chaplains?

Gregg – I think you’ve answered your own question – Europe is just a bit more secular, and certainly a bit more private about religion, thankfully (hey, I’m European!).

and I just can’t stand it when the likes of Gatlin start bragging on about their god given talents…. grrrr

Europe is hugely secular in comparison to the US; and especially western Europe. Data can’t be completely reliable, but in the UK church attendance is put at about 10% (which seems high to me), whilst it’s about four times that in the US.

I always laugh when people say things like ‘I’d like to thank Jesus’ after winning.

Assuming that the divine does exist, I suspect they have a lot better things to do with their time than influencing sport (although the omnipotence must help with this). Also, the counterpoint to this is that Jesus (or your deity of choice) was determined that your competitors should lose.

Conclusion? The Lord hates Greg Van Avermaet.

It’s possible for example to pray for good health so you can train and win “thanks to god” without any deity intervening to make your rival lose… and without insulting others.

Religion has its place in the peloton but it’s private. One aspect of the sport is the relative privacy afford to almost all the riders, their private life is usually off limits unless they chose to share it on social media. Only a few (eg Sagan in Slovakia, Boonen in Belgium) get the paparazzi treatment. Religion, relationships, “at home” interviews and so on are rare.

Personally I have no strong faith when it comes to religion

But its a personal thing, and perhaps best not to laugh at those who chose a particular path when it comes to believing in something.

It is a personal thing – and they should keep it that way.

There is nothing insulting about disagreeing with someone’s opinions – and that’s all these are, however much religious types might like to force others to accept that their opinions are sacred.

Many religious people are not shy of criticising atheism.

Also, as Buddha said, if you’re offended by something, that’s your fault: it’s your reaction.

Meh.

Ditto.

Church attendance or, fot instance, percentage of chuildren born to unmarried mothers are perhaps good measures of some aspects of religion as a social construct (or something like that) but not quite as suitable as measures of the significance of personal religion (or something like that) in different countries. I cannnot remember when I last visited a church when it wasn’t someone’s wedding or Christmas carols with my mother. but I would be somewhat uncomfortable if someone described me as hugely secular ot not particularly religious.

That said, I’ve had the impression that in Roman Catholic countries (with the exception of France and Germany) religion permeates the society including the sports to a certain degree, Church bells ring in Maranello when Ferrari wins, a Spanish cycling team visits a local chapel before the season starts, a padre blesses a new football field.

But it’s true that manifestations of personal religion are not loud or even all that common among cyclists. I find that they are more common for instance in athletics where it’s not at all rare to see a Polish or Italian competitor making the cross sign – or, these days, a sportsman of Islamic faith kneeling after crossing the finish line or simply sporting a beard.

PS FWIW I’ve always considered people who “don’t get the point” of religion or whose attempts are stymied by the contradictions inherent in all religions to be very much like people who “don’t get the joke”, i.e. who by accident of birth simply lack a sense of humour. It doesn’t make them a lesser person, but it is something that one has to make allowances for, (And for me religion is, in a nutshell, primarily a way or a tool or a system of not being a bigger asshole than I would otherwise be. And I’m pretty sure I stole that from Evelyn Waugh…)

But you don’t need religion – or a god – to have ethics.

Religious people often assume that athiests have no morals.

(1) Of course not, this is a very basic lesson. Religion, and a god, in the modern world simply have the potential to make one’s ethics more complex (and complicated), which in my book is always a good thing.

(2) This is unfortunately sometimes the case. And I completely understand the angry atheist’s view that religion mainly tends to turn big assholes into even bigger assholes.

You’ll see some riders wearing crosses around their necks. Some kiss them upon winning a race.

But thats as demonstrative as you find, these days.

And no, no chaplains.

Marc Madiot a Velominati? FDJ kit contravenes rule 14!

Sounds like a read with some depth to it. Sadly my foolery in French lessons at school means I will only be able to look at the pictures. Damn it!

“It’s why FDJ use white bar tape today and why when they have the French champion the jersey has no logos.” – an interesting fact. Any examples apart from Bouhanni?

White bar tape (and white gloves even in those years the jersey was blue).

French champions Nicolas Vogondy, Nacer Bouhanni, Arthur Vichot and Arnaud Démare and also Swedish champion Thomas Lövkvist, Australian champion Matther Wilson, Belorussian champion Yauheni Hutarovich and Finnish champion Jussi Veikkanen all raced without any logos (apart from that of FDJ). And so did the team’s ITT (Benoît Vaugrenard, Gustav Larsson) and cyclocross champions (Cristophe Mengin, Francis Mourey).

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%89quipe_cycliste_FDJ#Politique_du_port_des_maillots_de_champions_nationaux

Thx!!!