Liège-Bastogne-Liège is the hilliest of the one day classics. Glance at the race profile and you’ll note 11 climbs on the route, plus the climb to the finish. These are described as côtes répertoriées, or “catalogued climbs”.

Only the race has many climbs that aren’t catalogued. One in particular is crucial as it is climbed with less than 20km to go.

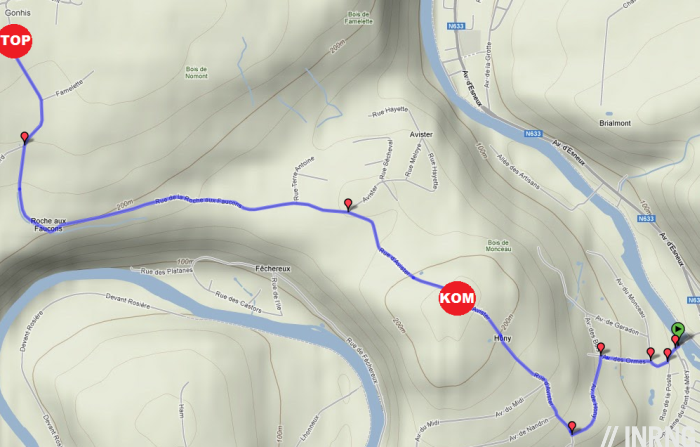

Since it was included in 2008 the Côte de la Roche aux Faucons (“Falcon Rock Ridge”) has become a strategic point in the race. With just 20km to go it is a make or break climb and in recent years has been the place where Andy Schleck has often put in a big attack. It’s tough, being 1.5km and over 9%. You start in Méry, climbing from Meuse valley and go up to the the village of Hony where there’s a line to mark the top of the climb and the King of the Mountains points. But if you think you’re done with the Falcons, forget it.

Then follows a brief descent of only 500 metres and then the road rears up again passing the limestone cliffs where the falcons nest, climbing up and up. In total there’s a climb that is 1.6km long and a gradient of 5.5% to the village of Gonhis, the top of the ridge. Only this climb isn’t mentioned.

Clearly you can’t “hide” a stretch of road, it’s not like Belgium is an unknown wilderness. Rather the organisers want to list only the most identifiable steep ramps and consequently there’s a lot more to the race than the 11 highlighted climbs.

The label of the Côte de la Roche aux Faucons does not mark the top of the climb, it is merely a staging post on the road that climbs up and away from the river valley. As such the identifiable climb is tough but anyone getting over the top needs plenty in the tank to turn a big gear on the climb to Gonhis which is just as long, although not as steep.

This is just one example from tomorrow’s route but it’s typical of the race. The steep ramps may serve as a launch pad for the most energetic riders and the specialist climbers but it is often on the exposed roads afterwards where the weakness of a tired rider is cruelly exposed.

You can see last year’s race in the Youtube clip below just as they start the climb. Andy Schleck goes clear with his brother and Philippe Gilbert on the first ramps of the Côte de la Roche aux Faucons. But later (7m30s) watch as the road is rising to Gonhis and Enrico Gasparotto and Jérôme Pineau are dropped as Gilbert gives it some torque.

I like this kind of detail, thanks.

Did it today and can’t say better. There is almost no flat section on lbl. Descents, climbs, steep climbs and the repetoriated very steep climbs. Brutal race.

Smart analysis. Looks like the perfect kind of place for a strong rider to attack because there will be a lot of tired legs.

ANY STAGE OF THE AMGEN TOUR OF CALIFORNIA IS JUST AS HARD AS LEIGE-BASTONE-LEIGE

Troll

@LANCESTRONG: You are wrong. Your statement is ridiculous because these races are apples and oranges. The ATOC is an eight-day stage race and LBL (LEIGE is actually spelled “Liege,” and BASTONE is actually spelled “Bastogne”) is a one-day Ardennes Classic. No comparison.

Not all stages in the ATOC are killer stages, a few are, like Mt. Baldy (Stage 7 this year), but LBL has so many ascents of varying pitches (all in one day), that the challenge of it can’t be compared to an eight-day stage race with a TT. Stage 1 ATOC is a mix of flat, rollers and great climbing, with lots of sprint opportunities (you don’t have that in LBL).

Some of ATOC is ridden at fairly high altitudes, not so in LBL. Both races are completely awesome but they cannot be compared in any way.

I live in Northern California and one of the most challenging climbs that has been decisive in previous editions goes through my hometown. The race has come through my rural, forested town

every year except 2011, but it’s back by popular demand for the 6th Edition of the race. Fantastic, steep, long climbs, but that’s not true for every stage.

The ATOC route changes a bit each year, but one thing doesn’t change — to get from Northern California (San Francisco, this year) to Southern California on the given ATOC route, riders will have some epic climbing for sure, but they will also have flat roads and rollers through valleys in between the climbing.

Some etiquette advice: when you type in ALL CAPS, it’s the equivalent of yelling at your readers and considered rude and immature.

Not until they start the contrôle anti-dopage out thurr in them hills of californy.

Har har : |

@Jim W: That’s for sure! I was dumbfounded when I read (months after the race was completed) that ZERO doping tests were performed during the 2011 edition. Sadly, it made me question Chris Horner’s two epic-climbing stage wins. He rode up the HC-categorized Mt. Hamilton and the steep finish on Sierra Road like it was nothing (again, NO blood doping tests during the race). Andy Schleck and Leipheimer finished 1:15 behind Horner, at 39 years of age! Hmmm.

Stage 7, another HC-categorized climb up Mt. Baldy saw Horner and Leipheimer kick ass and finish together, beating Laurens Ten Dam by 43″ and A Schleck by 1:39! Again, I say, “Hmmm.” In the GC, no rider was even close to Horner, except Levi, down 38″ in 2nd overall. Other than Levi, no rider stood a chance to overtake the yellow from Horner for the remainder of the race.

Unacceptable that no doping controls were used, and the story that the press was given as to why was a lame, cockamamie story. This huge blunder dampened my whole view of the 2011 race…wonder if Bruyneel knew that testing would be absent last year?

2012 will involve doping tests.

Ridden in the area too and it is relentless. Racing? Only for the specialists.

This is totally debatable, but here goes: so Andy attacks, and then Frank 1) closes the gap to his attacking teammate, and 2) drags Gilbert, the most dominant rider of the moment, up to his brother’s wheel? I have no idea the pain the riders are in at that point, but it sort of looks like the only reason the move goes is because Gilbert’s teammate does his team role and lets the gap go instead of pulling the pack up to his team leader…like Frank almost did. I don’t want to be overly critical, because I’m not there, they’re still hugely talented riders, and there’s the “heat of the moment” and all that, but sometimes I get the sense that these brother’s are their own worst enemies.

Anyhow, interesting piece. Can’t wait for the race tomorrow.