Ciao, here’s an overview of all the Giro stages. There’s the stage profile and a short preview for every day, as well as more on TV coverage and the big stages to watch.

If you want this info over the coming weeks it’s also at inrng.com/giro and available via the fixed “Giro d’Italia” link at the top of the page for desktop users or the drop-down menu for mobile browsers.

Route summary

Last year’s route suited the climbers, this year’s even more so with just 26km of time trials, the fewest since 1962… when the route didn’t have a TT stage but this reflects the trend in recent years where summit finishes don’t create big time gaps while even a short time trial can put minutes between the GC contenders. As usual the summit finishes get bigger and bigger leading to the Alpine third week. This time there are more chances for the sprinters compared to the past two editions too.

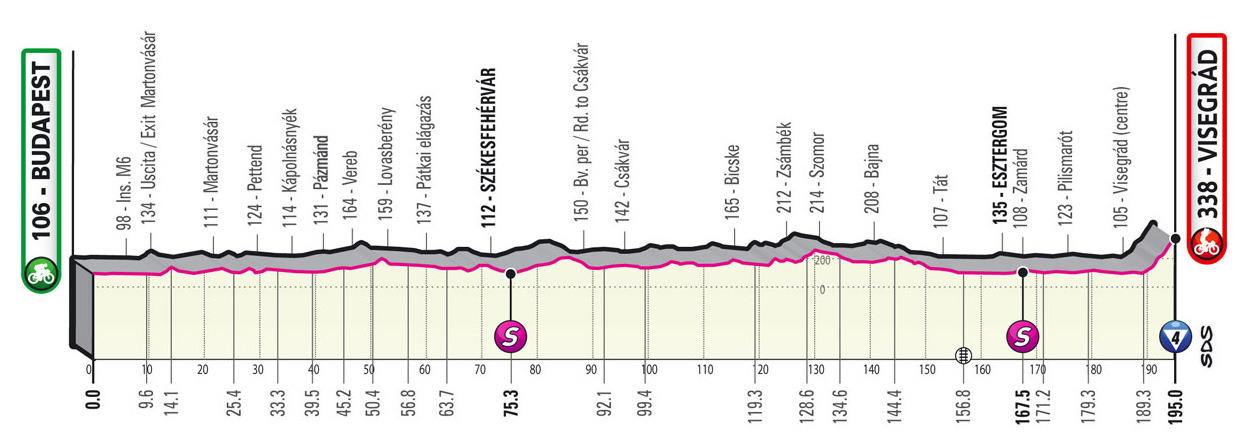

Stage 1 – Friday 6 May

A road stage to Visegrad and an uphill finish to the castle, it’s a touch reminiscent of the Namur citadel finish of the GP de Wallonie but longer and on a wide tarmac road. Here it’s five kilometres at 5% but the slope bites towards the top. This is a stage open to many, from in-form sprinters who can surf a slipstream all the way to the top, to punchy riders and the GC contenders too.

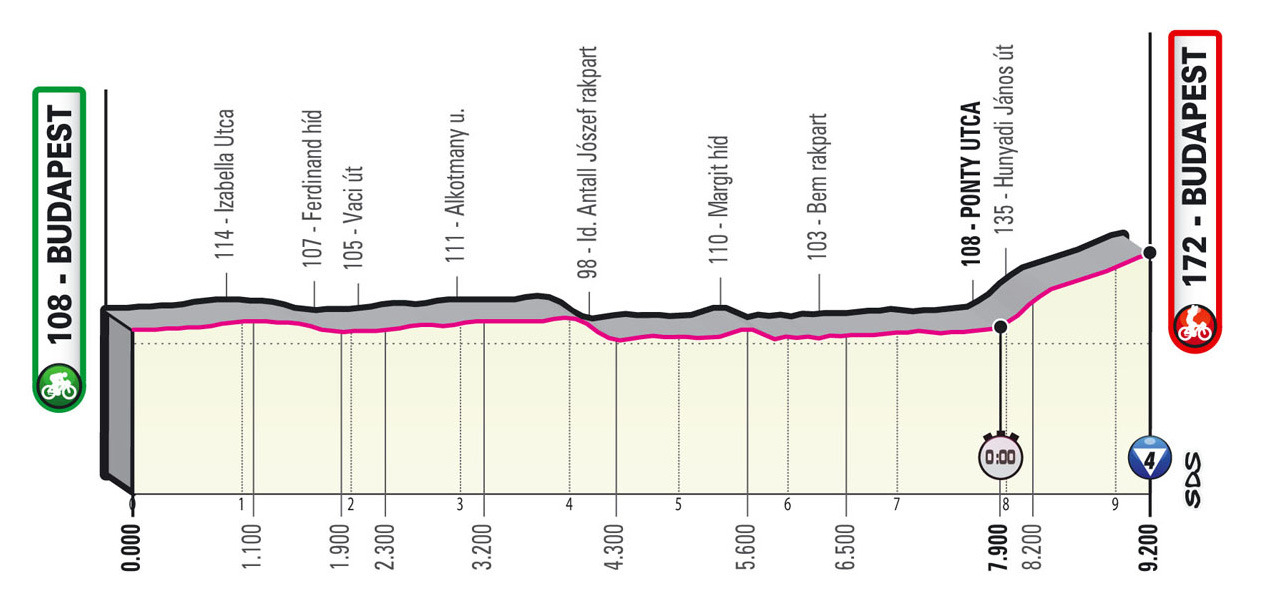

Stage 2 – Saturday 7 May

A time trial over 9.2km, it’s a big boulevard course designed to show off Budapest. The final kilometre includes cobbles with a steep kick up to the finish.

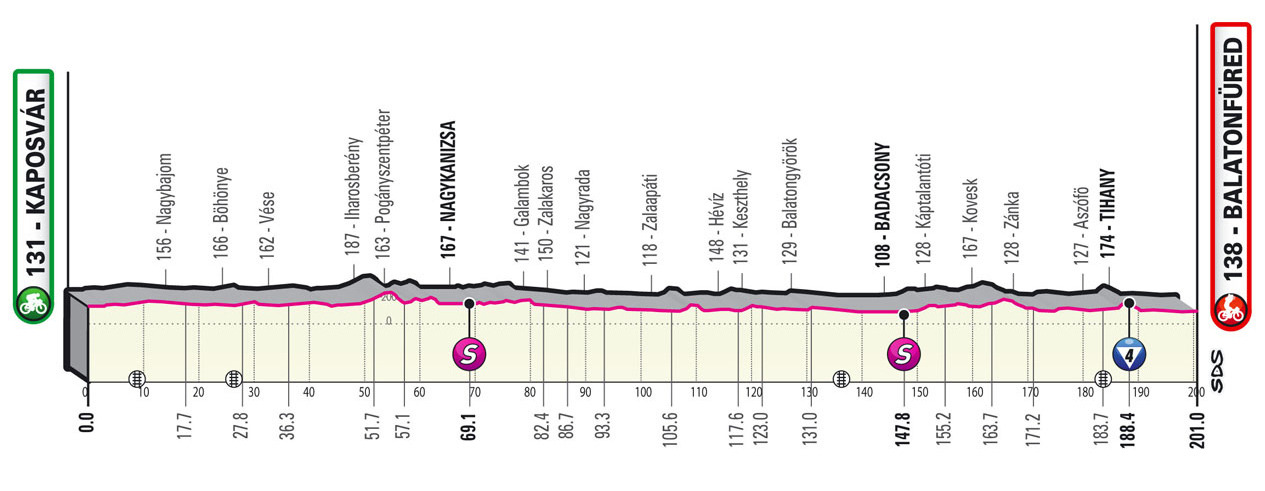

Stage 3 – Sunday 8 May

A sprint stage that ends on the shores of Lake Balaton.

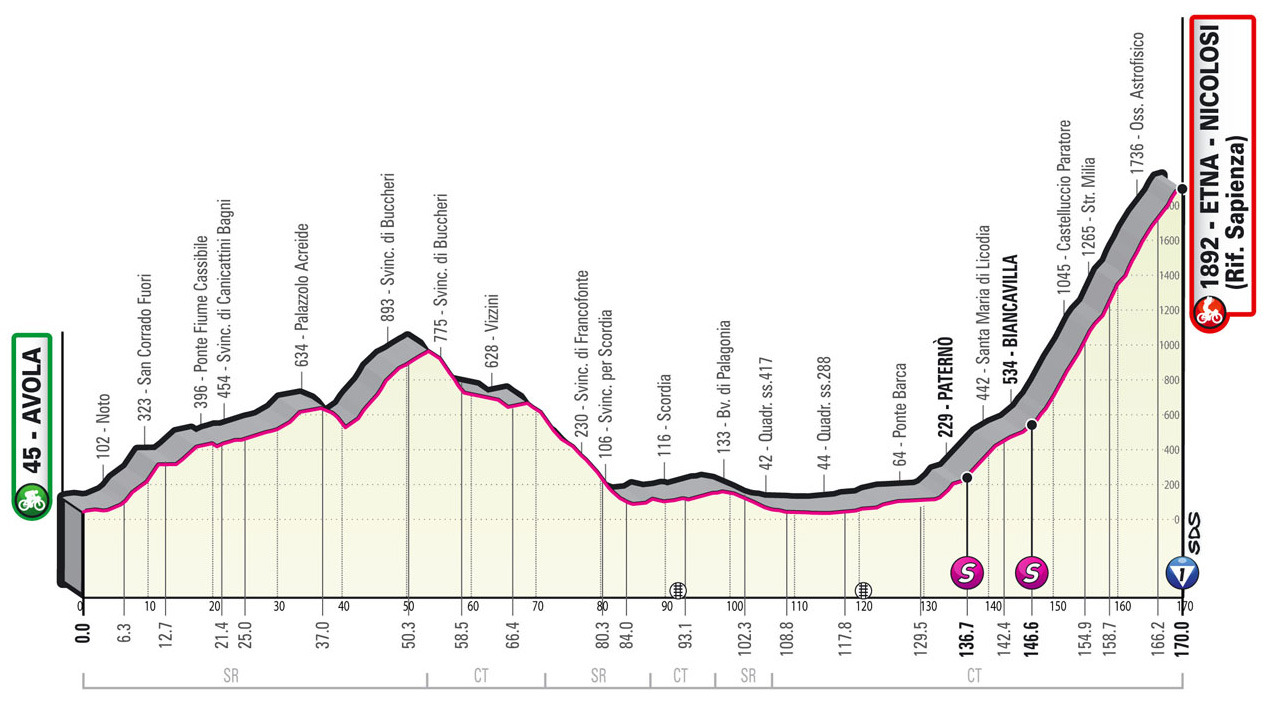

Stage 4 – Tuesday 10 May

After travel to Sicily and a rest day for the riders, a summit finish atop Mount Etna. It’s to the same site where Jan Polanc won in 2017, but to get there it’s climbed from the other side and there’s a steep middle section. Ideally it should provide an early skirmish among the GC contenders without big time gaps but Etna is a 22km climb and this could shape the whole race.

Stage 5 – Wednesday 11 May

The Giro has a lot of vertical gain and days like this help the count, the Mandrazzi climb is gentle but goes on for some time. It also offers the breakaway some mountains points and the stage should be for the sprinters.

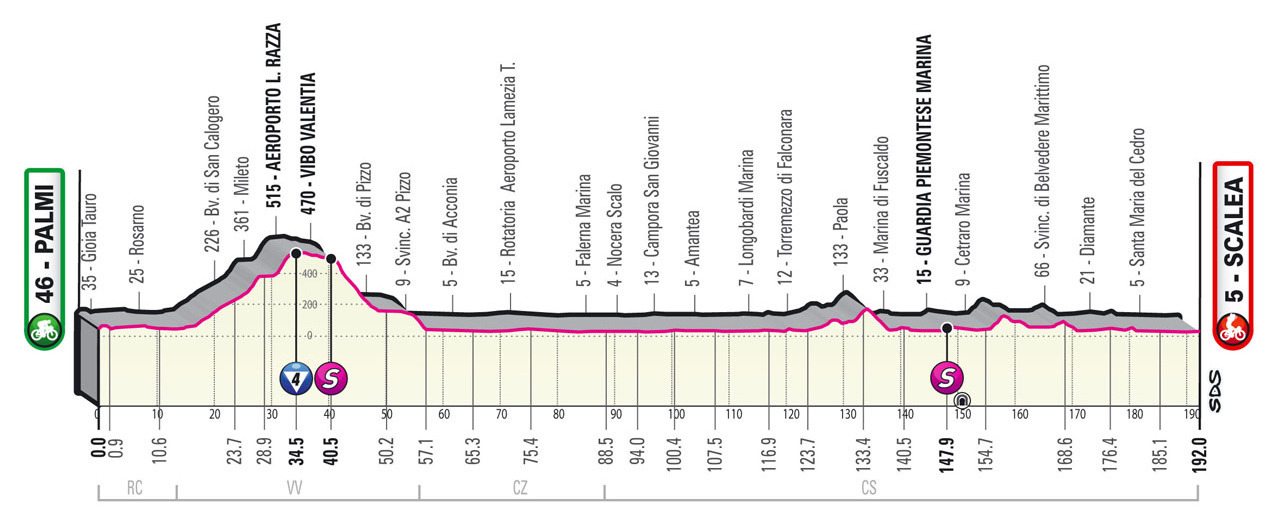

Stage 6 – Thursday 12 May

A trip up the citrus tree packed coastline for the sprinters.

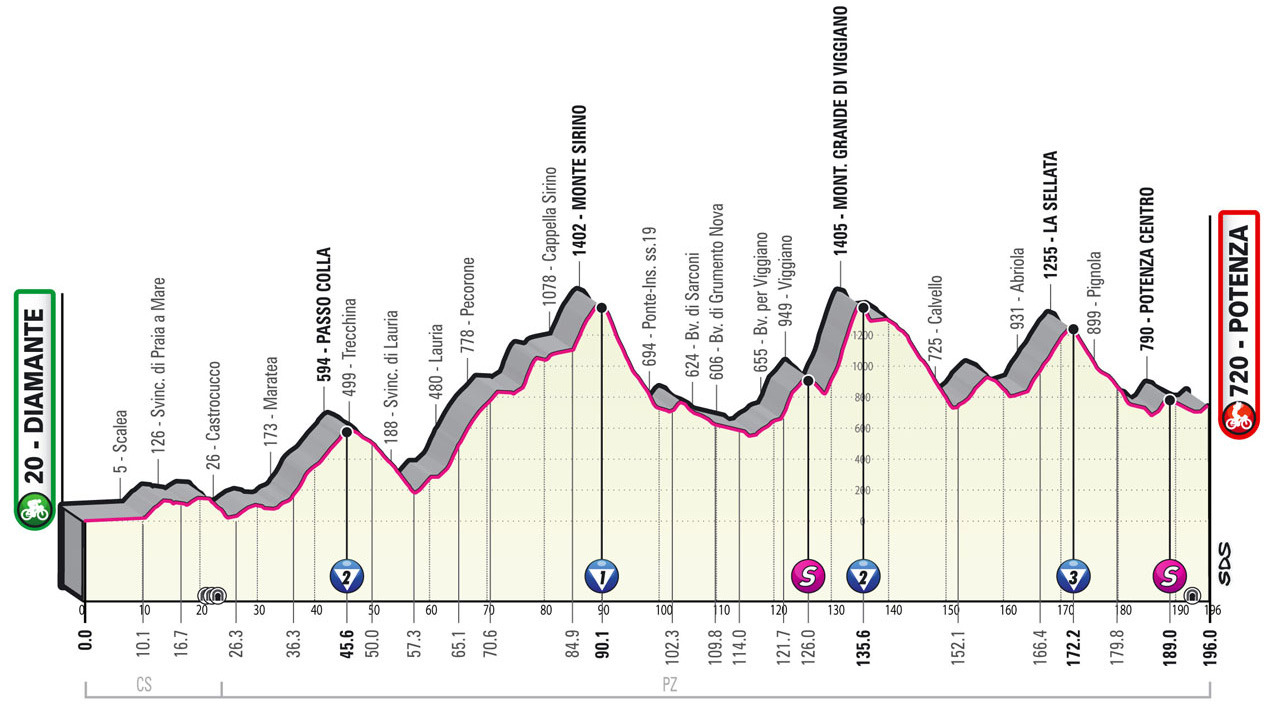

Stage 7 – Friday 13 May

An intriguing route with over 4,500m of vertical gain, as much as any Alpine stage and constant climbing and descending. With the TT and the Etna summit finish some will be well down on GC so there’s a good chance for the breakaway and for the current race leader post Budapest TT/Etna summit to lease the maglia rosa for a week to someone else. There’s a steep uphill finish in town but don’t expect medieval streets and flagstones, it’s a big road between large apartment blocks in the strange town of Potenza, a city in the mountains where locals ride escalators to get about.

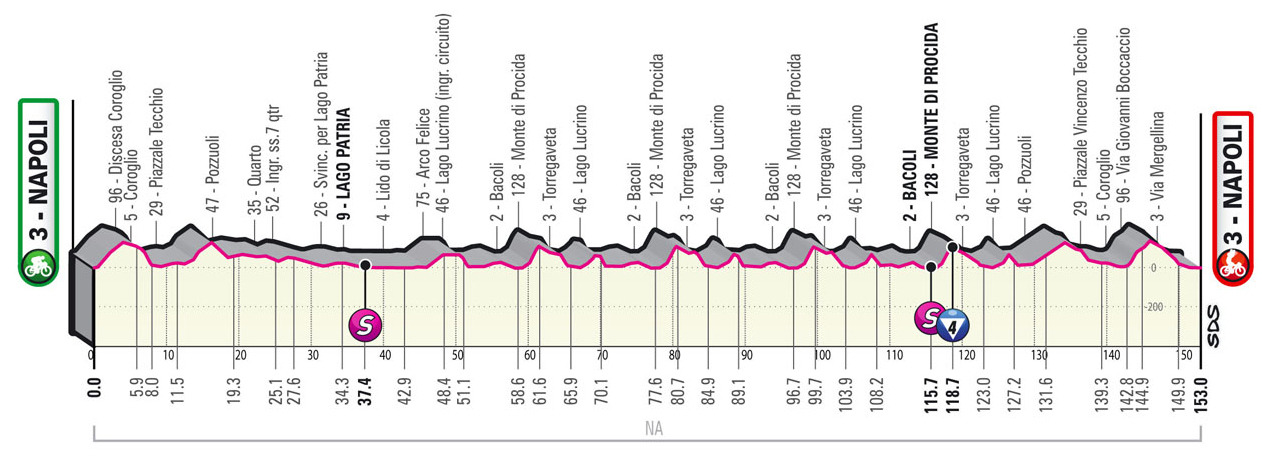

Stage 8 – Saturday 15 May

A circuit race around Naples, a hilly 19km loop repeated six times, it’d make a good worlds circuit.

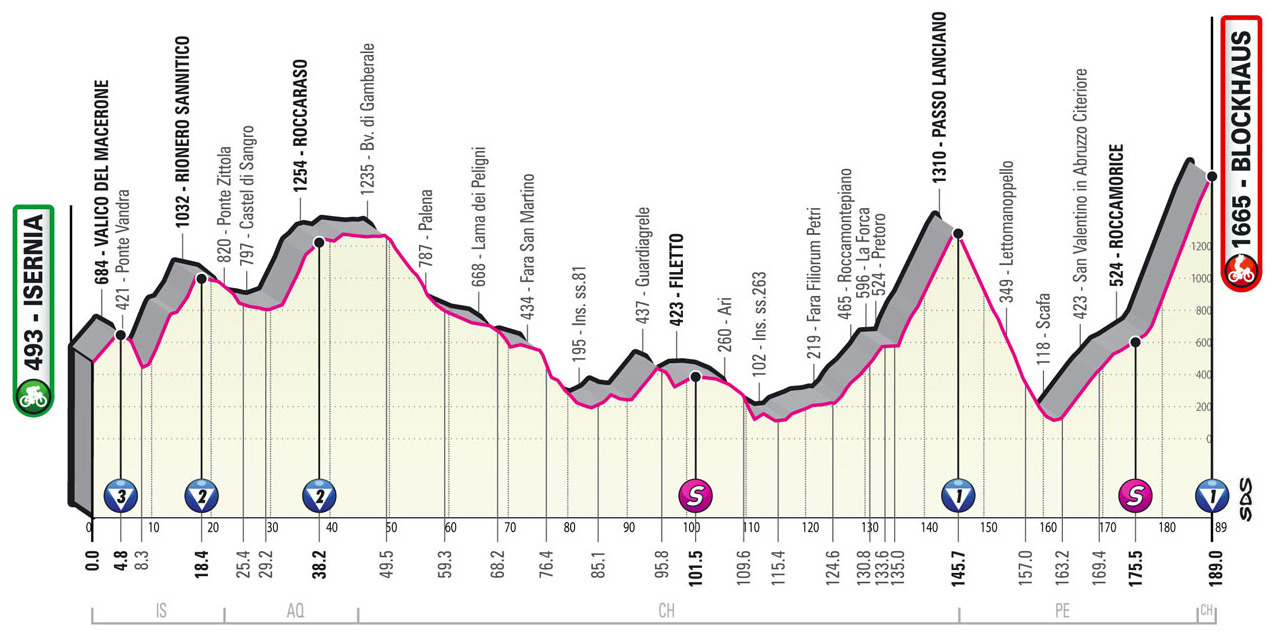

Stage 9 – Sunday 15 May

The big Blockhaus summit finish awaits. “Summit” of sorts as it only finishes at 1650m when the top of the road goes to 2,000m. But it’s enough, Nairo Quintana won here last time in 2017, beating Thibaut Pinot and the surprise of Tom Dumoulin. Talking of surprises, the race came here in 1967 and an infamous newspaper headline the next day was “Un velocista belga supera i nostri scalatori“, or “Belgian sprinter beats our climbers”… the young Eddy Merckx of course.

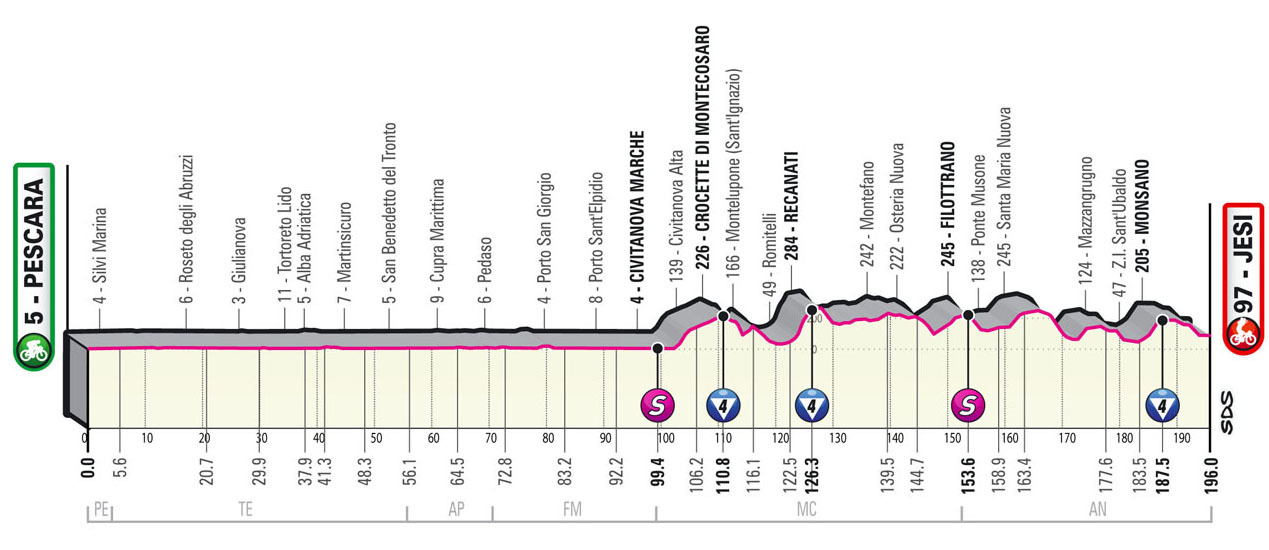

Stage 10 – Tuesday 17 May

A gentle start after the rest day up the Adriatic coast before turning inland. The hills of the Marche are steep (and often cracked and potholed) and a lot of sprinters can be dropped. The race borrows some roads from Tirreno-Adriatico and passes through Filottrano to pay tribute to the late Michele Scarponi.

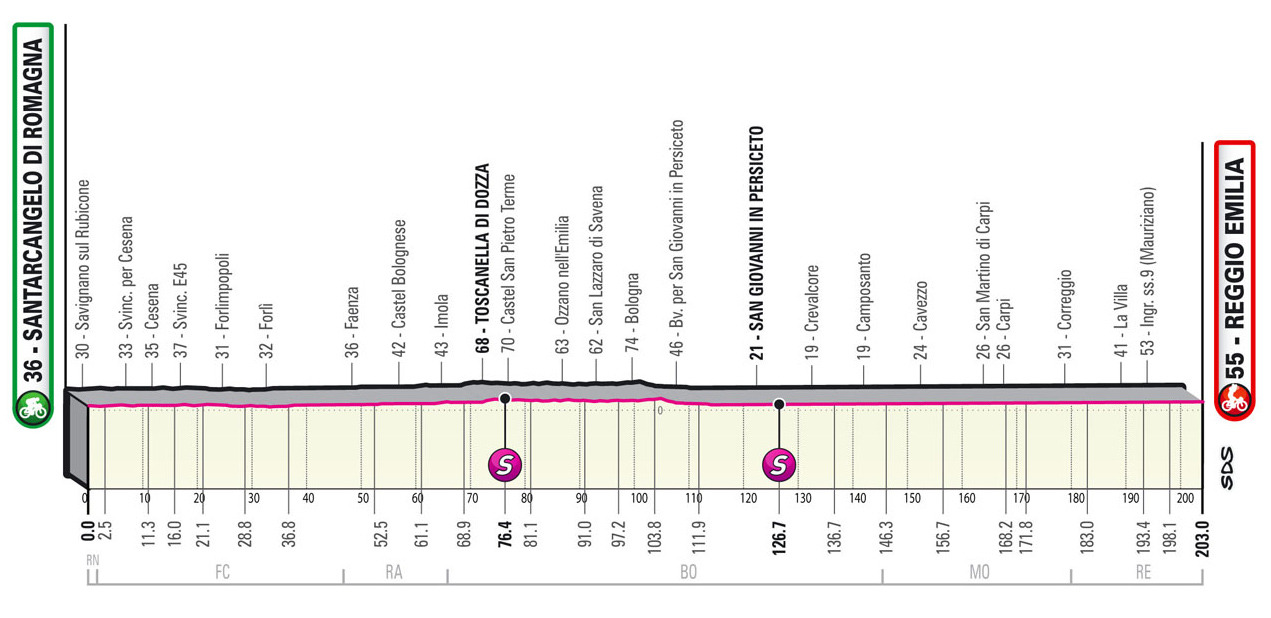

Stage 11 – Wednesday 18 May

A sprint stage and a classic, of sorts, as the Giro takes the Via Emilia Roman road once again. It’s being dubbed the food stage and will promote the famous Parmigiano Reggiano cheese.

Stage 12 – Thursday 19 May

Another intriguing route in the arid Ligurian hills behind Genoa because the final can reward attacks. The route’s been changed and softened a touch since the presentation last November and this is now the longest stage too, just. Monte Bocco’s not a hard climb but it’s the accumulation of climbs and twisting descents that should make for some sport. Away from racing the day will use the new San Giorgio bridge, built after the Ponte Morandini disaster.

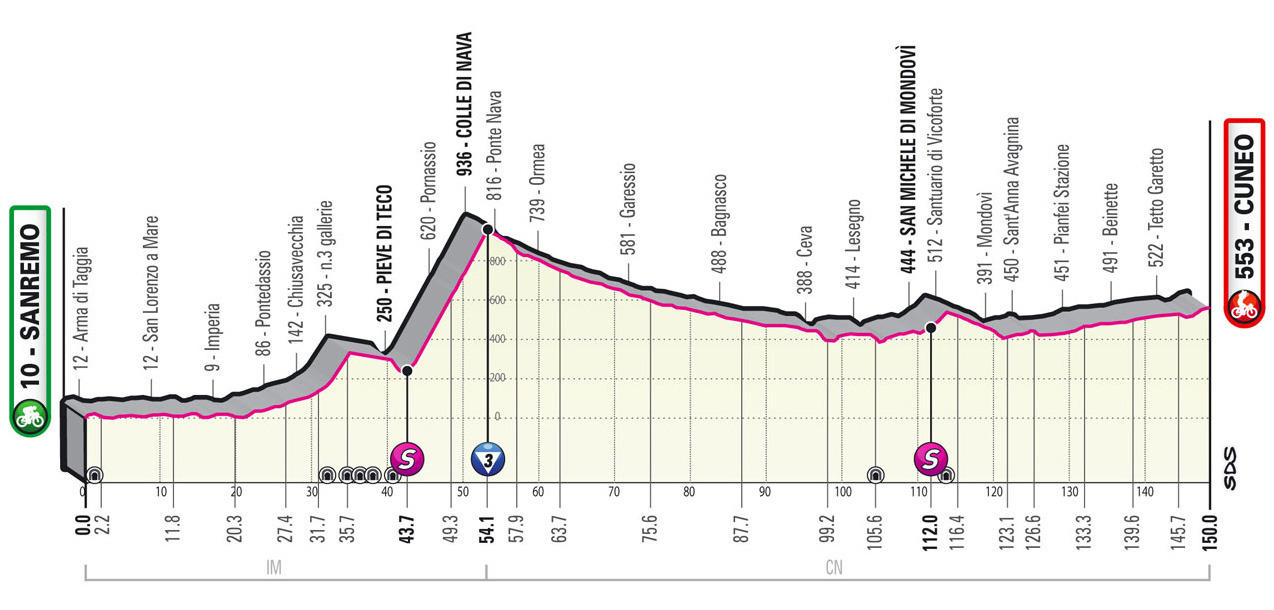

Stage 13 – Friday 20 May

The day starts in Sanremo and traces the route of La Primavera backwards for a while before heading inland – still on the Sanremo route but the exceptional edition of 2020 – to tackle the Colle di Nava and the outside chance a team forces the pace to eject any struggling sprinters. But with 100km to go there’s a likely sprint in Cuneo with the Alps now visible on the horizon.

Stage 14 – Saturday 21 May

Another circuit race, this time it’s got the Superga climb outside Torino and its sister climb across the same ridge, the Colle della Maddalena, plus the Santa Brigida climb and more. It’s only 153km but there’s 3750m of vertical gain and all on twisting roads, there’s little time to rest at all.

Stage 15 – Sunday 22 May

A mountain stage into the Aosta valley and instead of riding straight up the valley, the route rolls like a snowboarder in a half-pipe. First it’s up to the left for the Pila ski lift, then back down to the valley floor, then up to the right and back down. They’re both hard climbs and have been used by the U23 Giro della Valle d’Aosta race. The final one to Cogne is more of a gradual drag on the whole but you’d hesitate to call it a big ring climb because of the steep start. It’s the sort of place where Richard Carapaz could power away from the pure climbers and the race goes out of Cogne to finish in Lillaz, just as the Giro della Valle d’Aosta race did last summer.

Stage 16 – Tuesday 24 May

A huge day in the mountains, a reported 5,440m of vertical gain and at 200km, the longest of the mountain stages this year and presumably the longest day on the bike. Sure the Mortirolo is climbed via the easier side from Nonno but it’s still hard, plenty of 8%. The road to Teglio is marked as a sprint but it’s a tough climb to get there and the final Santa Cristina climb is almost always above 10% for the second half.

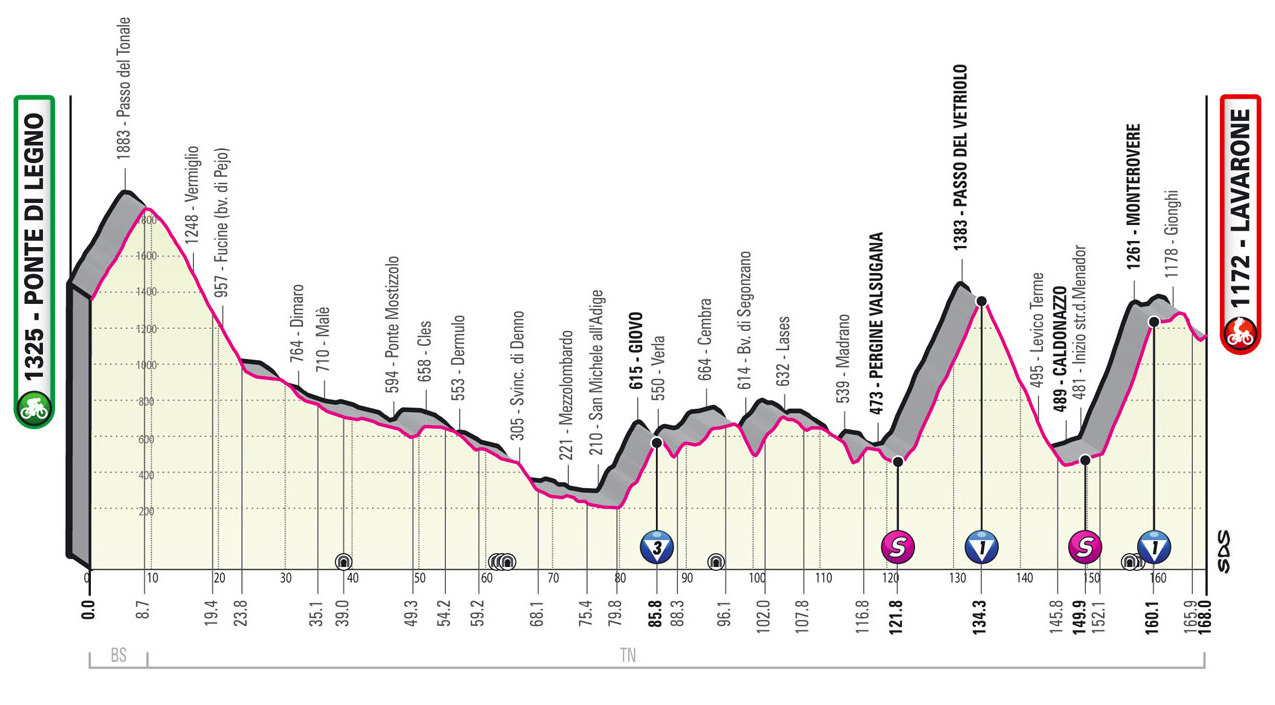

Stage 17 – Wednesday 25 May

The day starts up the Tonale, a chance for the breakaway to go clear but the battle could go on during the descent and the steep climb to Giovo could be needed. The “Passo del Vetriolo” is a tough, awkward climb – although the name’s an invention by the Giro, seemingly no such place exists on the ground – and the descent is toboggan-style to the valley and then comes the Menador climb to Monte Rovere, the Kaiserjägerweg road and one of the fringe benefits of history as this was an old military road, once built to kill but now a scenic ride up the cliffside and through narrow tunnels.

Stage 18 – Thursday 26 May

A sprint interlude and active recovery day of 151km but we’ll see which sprinters remain in the race and whether the breakaway can have an advantage. The Ca’ del Poggio wall features to spice things up but there’s 50km to get it together before Treviso.

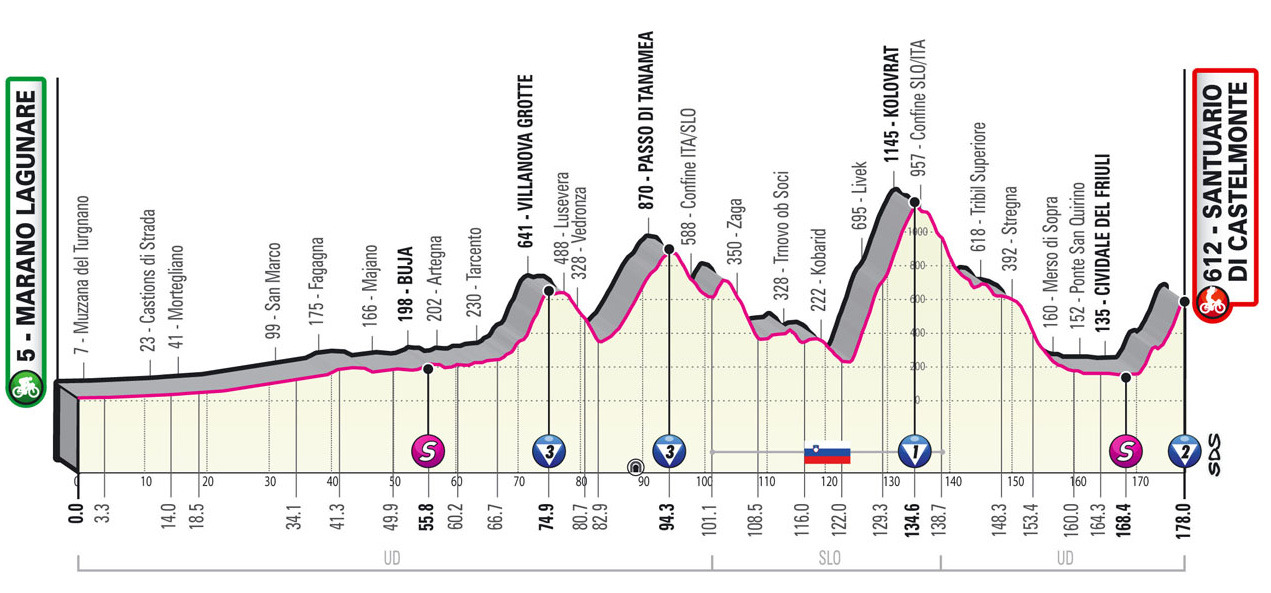

Stage 19 – Friday 27 May

A detour to Slovenia, the new Yorkshire, but first a dash through Buja, a village of sorts, perhaps even a collection of villages, but home to Il Rosso di Buja, Alessandro de Marchi, so guess who is going in the breakaway? Listed as a mid-mountain stage, you can make a good argument to delete the mid- prefix. Kolovrat is Slovenian for “spinning wheel” but good luck spinning your wheels here as it’s 10km of 10%. The final climb is 7km at 5% but note the dip in the middle, the final 4km are a more selective 7-8%.

Stage 20 – Saturday 28 May

The last hurrah in the mountains and a big day. There’s an early climb thrown in before a dash up the valley into the Dolomites and the steady San Pellegrino and Pordoi climbs before the mean Marmolada and its double-digit gradients. Weather permitting.

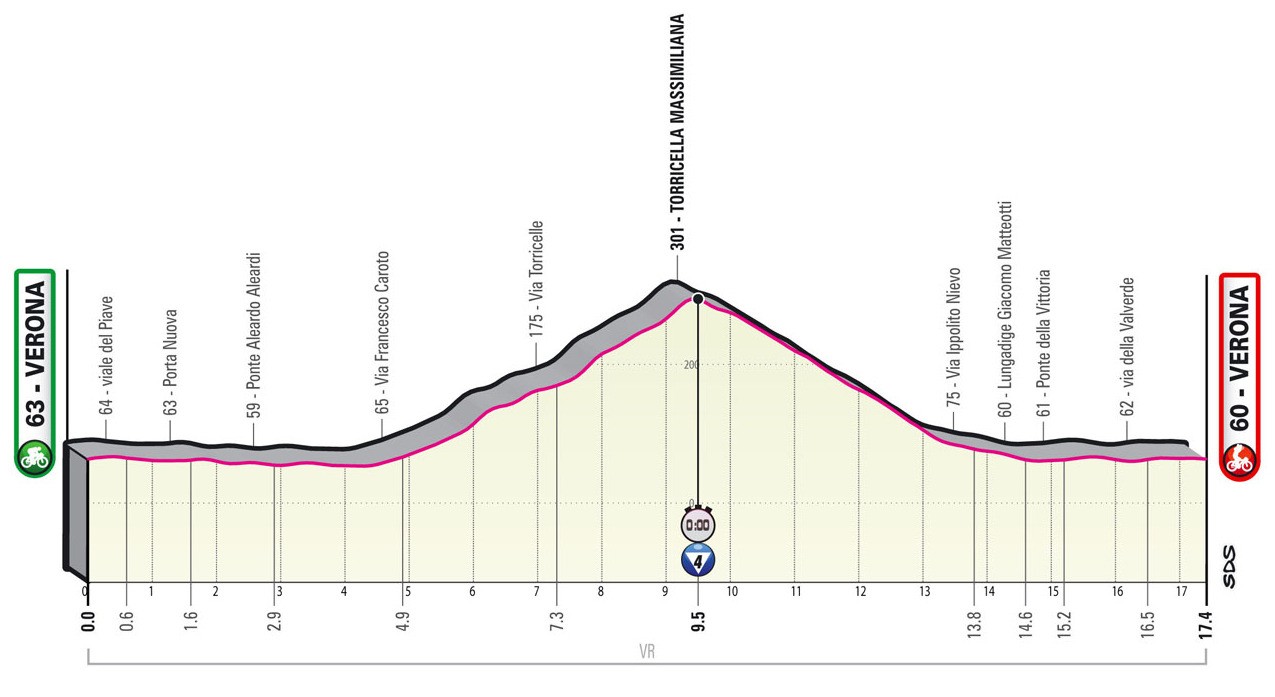

Stage 21 – Sunday 39 May

Verona and déjà vu with the same course where Chad Haga won in 2019 complete with the arena finish and where Primož Roglič overhauled Mikel Landa – of course – to climb onto the podium.

The unmissable stages

Anything can happen during the Giro but there are some stages that matter more than others, some suggestions for the must-watch days:

- Stage 1 because the maglia rosa is there for the taking

- Stage 4 with the Etna summit finish and to see if any GC bids come unstuck early

- Stage 9 for the Blockhaus summit finish

- Stage 14’s circuit race around the Superga makes for a hard race

- Stage 16 because of the Mortirolo and Cristina climbs, the tappone

- Stage 17 with more climbing and some tricky mountain backroads

- Stage 20 for the San Pellegrino, Pordoi and Marmolada trilogy

- Stage 21 as the final TT to settle the race

TV

All stages will be broadcast live from start to finish although we’ll see what this brings, it happened last year and the early phase sometimes had “lite” production means until the big show started later. After the fiasco of missing TV images last year because of wet weather, the production’s been outsourced from RAI to Euromedia who do the Tour de France coverage for France Télévisions which means if it rains we should still get the pictures.

Italian host broadcaster RAI offers the richest coverage with experienced commentators as well as roving reporters on motorbikes to add extra coverage, it’s on TV and radio in Italy and the geo-restricted website RAI.it. It’s also on Eurosport-GCN for English-language coverage. The timing varies but as a rule the finish is expected for around 5.15pm CEST each day.

On the face of it after a quick read through it seems like a very hilly race. God knows who’ll win, which is always one of the best things about the Giro. Looking forward to it, hopefully the weather will play ball.

Will do a preview for the GC contenders next week but for now Carapaz looks like the obvious pick although still with a question mark, with Yates, Almeida and Lopez close too.

Yes I’d have Carapaz as favourite but not to the extent that Tour favourites often are. I’d say there’s more chance of me winning than Lopez.

I get what you mean, still besides the very top favourite in current cycling there are not so many people who can sport two GT podia, Giro included (and at the Vuelta he was just a couple of minutes down that time!), plus whose worst placing ever in any GT was 8th: he got 6 consecutive top-10s in 4 years from 2017 to 2020 across the three GTs.

Of course, out of 10 GTs he started he didn’t finish… hummm, like 40% of them!, and that’s part of your point, I guess, but it could also be used to defend the contrary POV: i.e., probably he won’t finish, but – if he does – he could have a serious shot at the top. Even more so given that ITTs (and descents) often were a problem for him but this time they’ll face much less of that.

It’s not like you could really say he’s not able to finish the work, either, at least when in proper conditions, given that he brought home heavyweight stage races like Suisse or Catalunya (and Andalucía). He’s also one of the very few who could beat the top dogs in a direct uphill duel.

After all, the heaviest factor against him might really be the team (because of this season’s general performance and internal situation)… or not! They could put up a solid line-up, at the end of the day, thus so much will be about the way they use it, and if several names will be able to comply with their potential (even *current* potential, I mean). A big bet, but it could be fun.

Richard S,

I can hardly wait except for the curveballs.

Hilly yes, although very little over 2,000m elevation I hear. With peloton illnesses and travel to mix things up and puncy climbs early on it could be a vintage year!

Cannot wait.

I will be visiting for the Treviso stage (stage 18), any tips to see the stage the best way please?

My tip… would be to go and see the start, it’s not as closed off as a Tour stage and so you can see the riders in between the signing on village and the team busses, plus as it’s late in the race everyone will be a little more relaxed (or just tired). Then if you can drive to the finish you can see the likely sprint but that does mean being in place for a long time, aim to get a line of sight to both the road and one of the giant TV screens.

“Last year’s route suited the climbers, this year’s even more so with just 26km of time trials, the fewest since 1962… when the route didn’t have a TT stage but this reflects the trend in recent years where summit finishes don’t create big time gaps while even a short time trial can put minutes between the GC contenders.”

Actually, as it’s manifest in the graph above, the Giro comes from a nice 2013-2020 trend of having decent ITTs, unlike the Tour. And – again, unlike the Tour – you can feel assured that most times summit finishes delivered very fine gaps, which indeed allowed the race to stay open “despite”, so to say, those ITT kms.

It does feel, in hindsight though, that the Giro spent a considerable part of the 2010s unsuccessfully dangling an ITT carrot in front of Chris Froome?

Maybe as an unintended consequence, in part at least, it spawned Tom Dumoulin and then finally the epic showdown between the two.

The Slovenia stage tells its own story this time round.

I always get the feeling that the Giro course design has a ‘buy me’ tag on it, where La Tour can give an indifferent Gallic shrug of the shoulders or is blatantly tipped to suit, never an in-between?

Barely any reason to go for Froome before the 2015 edition included, or after 2018. They were actually after Contador once he had proven in the 2014 Vuelta that he was still on the very top – and they happily got him. Quite obvioulsy, top GT champions tend to be all-rounders, hence they fancy a complete course, and obviously again the Giro must strive to have them in. Froome might be the exception in that he thrived on courses which were as a whole lighter than average both in ITTs *and* mountains, which is precisely what the TDF duly offered him after 2015. And, guess what?, check 2018 in the graph above… The Giro went for Froome in 2017 and 2018, while 2016 was still pretty much an anti-Froome course, as in “just in case Froome comes, let’s make sure Nibali can get a win” 😛

Ha, true enough.

The decade-high TT totals of 2013 and 2014 were possibly bait to entice Wiggins too, and he was duly caught, hook line and sinker as it turned out.

These days, other than Pagacar, is there an absolutely stand-out GT favourite?

I’d say not, a good contest can be made amongst a range of riders, where the ITT is not necessarily the be all.

End all, certainly enough, but a competent ITT can be sufficient.

Maybe why the Giro has reeled in the ITT bait, the big fish (other than one very hungry Slovenian Pike) are chasing a different prey.

I’ll have to stop with these analogies, I’m getting more like Carlton Kirby every day 🤣

I would say Roglic is standout favourite for any stage race he enters but Pogacar does not.

Backtracking what I wrote below about sticking to present times, let me also track back Wiggo to his 2014, as you hint above… when frankly no con could bribe Wiggo back to the Giro, neither RCS would be cheated again to pay for such an ex GC rider. The Giro undid Wiggo for good: in terms of GC what was left from that 2013 May on was mere Tour of Britain or Tour of Cali stuff – at the very most. And, unlike 2013, now everybody knew. The local-Olympics magic was gone. Not that he was an ex rider, of course: still huge engine and class act, ITTs, Hour, Roubaix….

Surely, 2014 wasn’t for him.

It was thought for a Quintana-Nibali duel, if anything (reminiscent of that iconic Nibali vs. Colombia 2013 snowy finale), although luckily for him the latter would not eat that bait. Quintana was the rising sensation, especially suited for the Giro, and a fresh TDF runner-up. Aru worked for the Italian public, anyway, and a solid Urán.

Speaking of Urán, the Barolo ITT wasn’t even looking like half good for Wiggo, he wouldn’t be tricked as he was by the Marche one the year before.

All in all, I think that although RCS was clearly campaigning to get a starry startlist, often achieving it, truth is that great course design and hence great ITTs were also being made for the pure sake of it.

Ignoring how he might have achieved such dominance, I don’t think course design would have made much difference to Froome’s TdF palmares. Maybe my memory’s failing me, but it only seemed like 2015 where he could have lost.

Which, on turn, depends partly on course design.

However, I agree quite much on that conjecture, only the debate wasn’t as much about supposed winning chances as well as about Giro organisers trying to lure in a rider with an appealing course (eventually even with some slight but important changes before official releasing it, once the rider in question has confirmed he’ll be at the start).

Anyway, Froome always liked better a course with predictable efforts.

But know I’d rather stick to current sport… (yes, I know I started it or at least jumped fast right when Ecky made his move ^__^).

He lost in 2014

Gelato4bahamontes, he lost in many other years as well. We were talking about the races he’d won.

If Slovenia is the new Yorkshire, then I feel for it’s rain soaked, wind battered residents. Perhaps it is this inclement climate that has made the current crop of Slovene riders so strong, or is there a local equivalent of Yorkshire tea we should be told about?

Thanks for the summary. That will help with viewing no end.

Looks a good parcours, although 202km being the longest stage is disappointing, but then you want the riders to actually ride it… Similarly, hopefully, this year they’ll somehow manage to ride up mountains in rain without chunks of the stage being cancelled – maybe if we actually get TV pictures there will be more pressure on them to do so.

Thanks very much for this – it’ll prove invaluable once I no doubt get days behind on the race and can no longer check daily previews.

Looks like a fine course and as always, an excellent write-up. “Dolomotes” should be “Dolomites.”

yes, thanks!

and “Nonno”, Monno

Beyond Cav not sure what sprinters will be lining up but good to see the early part of the race has a good few “sprint” stages, though I doubt many sprinters will hang around for the jersey.

Snow unlikely to be an issue this year, it has been a very “unsnowy” winter, many alpine passes are opening early. Sadly no images of the riders riding amongst huge snow walls, not sure we will even see many snow patches.

For all the talk of a “climbers” Giro this course does not seem to hit the heights of the recent past (no Stelvio, Agnello, Finestre, Nivolet or Gavia) which probably is to the benefit of Richard Carapaz.

The Giro always brings twists and turns but not sure this route promises a “classic”, think more likely something along the lines of 2019 rather than the drama of the 2016, 2017 or 2018 races. Though Italy in May tends to be more unpredictable than France in July.

I notice that the uphill finishes actually finish on or not to far from the top instead of chasing the $ and finishing in the valley somewhere in a town willing to put up some cash. Which i much prefer to the finish in the valley somewhere making the riders risk there life and often neutralising the efforts of a solo rider (so nobody tends to attack).

Summit finishes seem to end without attacks, except for a final, short sprint, just as often as those which end after a descent from that summit.

And nobody makes anyone risk their life. It’s a choice to ride, and it’s a choice as to how quickly you descend. If you’re not good at descending, do it slower.

Most races include descending – it’s part of the sport, just as much as ascending. It’s also a skill, conferring an advantage on the proficient that doesn’t just rely on physical ability, which with a DS on the radio telling riders how to ride is ever more rare in cycling.

Cardiac arrests and being hit by vehicles are two events that are far more likely to cause the death of a professional cyclist than via crashing on a descent (or anywhere else for that matter).

https://cyclingmagazine.ca/sections/news/a-history-of-professional-cyclists-who-died-from-heart-attacks/

The fact that the rest of the sport is dangerous does in no way make adding unnecessary dangers acceptable. A poor descender will still loose out in the long run but putting a finishing point at the bottom simply means that some will take risks they shouldn’t. Riding is dangerous but when i am riding if there is a safer rout or finish point i take it.

Even if an attack on a climb comes near the end its often set up from a long way out with pace setting, chasing attacks down, softening attacks etc. When you put the finish at the bottom especially if its a bit further often none of the teams bother doing anything when if they had been finishing at the top entire strategies might have played out to at least attempt to set something out.

It doesn’t happen in every case but it happens a lot more often when you finish at the top.

We could argue for or against such an idea forever. But, empirically, how many serious crashes with relevant health consequences happened on the very final descent of a stage? Neither a rhethorical question nor a provocation: I’m just trying to remember the occurrences of terrible crashes and while I can recall several of them relatively far from the line (at most, down the penultimate climb or anyway tens of kms away from the finish), I struggle to come up with a case on the very final descent after a selective climb of sort. The closest I can get is the Brasil Olympics… but that was a circuit!

Now I guess I’m forgetting something impressive or very serious, of course, but all the same I’d suggest to weigh the supposed risk against the actual possibility of such a thing happening, for which decades of pro racing should provide a decent sample.

We shouldn’t give away quite significant sporting aspects for the sake of reducing a risk which is empirically extremely limited (remember that we’re speaking only of the very last descent as an alternative to hilltop finishes).

The two descents are not so steep, the have very steep ascents before but once at the top the way down is much gentler. Lavarone off the Menador/Kaiserjägerweg is a big wide road and the one into Aprica is smaller but not as steep. Sure someone can overdo it on a climb but in the same way they could do it on a roundabout etc, this time neither finish feels too risky.

Even when speaking of racing dynamics, sheer historical experience plays quite much against what you defend. Quite the other way around, actually! Lots of examples from this very same season and in recent weeks – even this same week, I’d dare to say. Of course, everything can happen on every sort of course, but a very hard uphill finale prevent complex action beforehand. Even team work tends to be focussed on keeping things tight and sort of “homogenous”.

Generally speaking, the fact that the descent can shuffle cards again forces those who have a margin climbing to go all in, or you just lost your occasion and full stop. Whereas if it’s an uphill finish, climbers do know that they’ll gain something anyway, be it a little or a lot, so they’ll stick to a more prudent, much more prudent, risk/benefit balance. You can counter such an attitude through course design, for example introducing ITTs which supposedly should force climbers to get time back, but this doesn’t always work for a series of reason, most of them related to human psychology ^__^ (the “subsequent descent so I need to go very hard uphill” effect is more inmediate, whereas all the past-present-future stuff like “hey, I need more time, there’s a final ITT” doesn’t work as much; plus, if the ITT is sooner in the race, several riders will feel just ejected from GC and won’t give their all – no actual rational reason, indeed, but most humans tend to work like that).

Guess what? As always, the best thing would be to have a mix of sort, and maximise welcome effects while limiting the others. Easier said than done, I guess. However, the Giro has been doing great in course design during the 10s decade (which indeed was rewarded by huge racing most of the times, albeit not always) – I suspect that some regression to the mean is to be expected.

Playing Devil’s Advocate here somewhat, and not necessarily debating descents, but the hazards, risks and outcomes of serious harm and injury in road cycling is pretty damn high compared to any sport.

This weekend has seen two women battering the bejesus out of each other for a reported ten figure reward each.

Yet Amy Pieters just awoke from a 4 months coma after a training accident, Bernal, Froome, the list is endless and crashes happen more or less every race.

If people complain of inflated salaries or too much money in cycling, I don’t know.

We’re talking of elite sportsmen and women, and I don’t begrudge them anything, not one euro for what they earn.

This is a totally random question, but why do we not have team time trials in grand tours anymore? I’m not certain if a TTT ever decided the outcome of a race, but I always thought they were beautiful things to watch.

They do appear from time to time. They are not popular with some teams & riders as it is possible to loose considerable time through no fault of the rider. The old cliché applies, you cant win the race on a TTT but you can most certainly lose it.

They are sort of fun to watch but TTT unless they are very short really affect the race and they certainly did in the past.

Loosing 2 or 3 minutes right at the beginning of a 3 week tour pretty much means your out unless something unusual happens.

Pretty much if there is a long TTT and your on a smaller team and have ambitions of winning or podium the GC go do another race instead because GC riders on another team will gain minutes on you.

We’ll see one – without nasty crashes, I hope – in this year’s Vuelta.

The previous TTT in a GT was, I believe, also in Vuelta, 2019. (2020 would’ve started with a TTT, but it was dropped when the start ad to be moved away from the Netherlands.)

It’s a good question, though. If we accept that team strength is an essential part of individual success and that a correct choice of riders that can perform certain roles is as important as wisely chosen team tactics in a normal stage, then we cannot argue that GTs should be races without a TTT.

I don’t watch them and I don’t like them – but that is probably because the riders I keenly followed and hoped to do well were almost invariably riding for a team that didn’t do too well in a TTT 🙂

It is a team sport – to an extent. But it’s also an individual sport.

With a TTT, the strong – wealthy – teams have too great an advantage. Their top riders already have enough of an advantage without giving them minutes on their rivals on smaller teams.

Would one really want to see a rider win a GT because their team won them a minute on their better rival in a TTT?

For me, a TTT tilts the race too far away from the individual.

The rules say you have to have it early in the race and the problem is that it suits the big budget teams who can squash smaller squads as they can recruit riders who can climb and roll well. And while there’s a lot of technical and performance issues for people like you and me to enjoy, remember the vast majority of the TV audience probably doesn’t know a skinsuit from a jersey and so it’s a hard sell.

I love the technical aspect, plus I find it spectacular (…or decent, at least ^___^) viewing for the general public, too: i.e., not that uglier than a normal ITT – which, of course, tends to be nearly always a TV failure.

Yet, I agree 100% with what J Evans points out.

And for some reason most sponsors (especially but not exclusively those which are rich & powerful) like them a lot, of course – including those who end up losing, which I cannot understand fully. I suppose that TTTs at least provide fine photos for your office or desktop.

Sometimes, although as we as regular fans could find it surprising, GT organisers actually sell predictability to a vast range of powerful sponsors and institutions, not the other way around. Well, in that sense TTTs work great precisely because of the reasons which make them less likeable for me or J Evans.

So, leaving aside sponsorship plots and focussing on the sport & spectatorship experience, perhaps it’s about pushing hard on the visual aspect (TDF obviously did it great with impressive bridges and the likes, but Italy can provide interesting sceneries, too; while Vuelta once went too far and right into grotesque with that beach stuff).

Besides, the idea should be to spend it as on of those “useless” stage – much needed in a GT, paradoxically enough!

The TTT can be short, in order to avoid significant gaps, and might respond to the same function of a prologue or a first sprint: handing over a more or less random leader jersey to create a little intrigue about the winner keeping it or other supporting characters trying to have their first week glory stealing it.

This doesn’t need to happen as the first stage. You can have a sort of sprinters/puncheurs battle for 3-4 stages, than the TTT to shuffle the cards. Or something like that.

The TTT also allows the team to award “internally” the jersey to a rider who wouldn’t win it but who’s career, team role or whatever can thus be acknowledged (not to speak of the possibility of fun situations like Di Luca & Gasparotto in 2007 ^___^).

Or organisers can use it as a recovery or transition stage of sort a little later on. Of course, top contenders will need to push hard all the same, but if it’s a twenty minutes effort and it’s shared, it will nevertheless work as a light stage.

All in all, I’m not missing TTTs so much, neither would I consider it a flaw for a GT *not* having one, but surely they’ve got some interesting aspect that can be fit into a GT if organisers feel so. As everything else, it must be done properly. Curiously enough, short stage races also use them, but I find that in that context TTTs make even less sense (generally smaller GC gaps, hence greater TTT impact even if you design a short one; and “useless” stages aren’t needed as much in a week or less of racing).

Does anyone know if Sean kelly will be commentating on Eurosport for the Giro? Or do I have to “put up” with some of the others.

I think I saw a tweet from Daniel Lloyd saying Kelly is part of their team.

You are not alone in missing Sean Kelly, he has insights that the other commentators just dont have. He has one of the most impressive Palmares in professional cycling and a deep understanding of the mental and physical effort required to be a “winner”.

Sorry, anon was me above asking about Sean kelly, sounds like good news to me.

Plus:

– nice balanced mix for the Grande Partenza, which starts a notable and quite hard first “week” (until Blockhaus on stage 9 included)

– a couple of city circuits which are well-designed and promising

– some impressive hilly & tricky “mezza montagna” (so to say) stages (7, 14, 19… still a pity that Genova’s stage was lost to this category for road security issues). Napoli, Jesi and Genova shouldn’t now include much GC risk (who knows), but they’ll also be very fun for stage hunters.

– two very good mountain stages (Blockhaus and Lavarone, with the former being extremely hard, too)

– decent number of occasions for the sprinters, but without exaggerating or becoming boring: you only happen once to have two of them back-to-back

– weekend stages will be nice with a good balance between the TV show and roadside public (sometimes it’s a trade-off)

– fondo isn’t totally lost because we’ll have hard, decisive stages well deep into the third week, and although length has been reduced, still I’d guess that we’ll see at least three serious stages longer than 5 hours (and maybe even up to five).

Minus:

– nearly absolute lack of ITT kms

– no mountain marathon, although the Aprica stage comes close

– you pretty much never have three consecutive hard stages

– too many uphill finishes (Lavarone and Aprica actually are), in that sense there’s a lack of variety when the finale of hard stages is concerned.

– apparent contrast with the former (but not really): lack of concentrated altitude gain in the finale of mountain stages (as in 2017, although it’s not that serious thanks to the above point); to put it simply, we lack “very consecutive” hard GPMs which may prompt mid-range attacks: they’re available only in stage 9 (too soon in the GT, perhaps, for this kind of moves) and in stage 17. I’ve got some hopes for Verrogne or Kolovrat, very good climbs, but they’re *more than 40 kms* away from the finish line. Applause if the riders do try.

– sprinters won’t need to fight much to bring their stages down to a sprint. With the likes of van der Poel or Girmay at the startline, it’s a pity. Some little hill 10-15 kms away from the line in some of the sprint stages would have added interest: Balaton, Scalea, Reggio, Treviso are *pan flat*, and Messina or Cuneo can be considered such, too, in practical terms.

– The “second week” (stages 10-15) is a little too weak, especially after the Genova stage was changed. Val d’Aosta Sunday stage could be fireworks… or a reduced group sprint of sort like what we just saw in Romandie (very disappointing).

In general terms, and if one wants to be pessimist, this could be a subtle (not that manifest, indeed) traison to the course style which created great Giros in recent years. The risk – just a risk – is having little selection at first (Etna), than a lot of repeated final uphill battles, with a different outcome each time (or not) and a lot of previous waiting, while long range moves are rare and desperate. Sort of a ’10 years Vuelta on (heavy) steroids – by the way, please note that the Vuelta also changed its course format recently, and in a very positive way which was promptly mirrored by racing. Let’s hope that the optimism of will is going to eventually prevail!

Hard to go for a middle range lone raid, as I said, but, OTOH, there are several occasion in which, if a strong team is deployed strategically, with solid gregari soon up the road, a concerted long range attack – or selection – could become devastating. You’d really need old times Martinelli at his best… but on a team with Bahrain-like form ^__^

To me this paragraph is the most exciting:

“After the fiasco of missing TV images last year because of wet weather, the production’s been outsourced from RAI to Euromedia who do the Tour de France coverage for France Télévisions which means if it rains we should still get the pictures.”

Fingers crossed we won’t be tuning in for a big mountain stage only to be greeted with stationary finish line images…