French magazine Le Cycle has labelled the Mont du Chat “one of the hardest” climbs in France and it’s back on the route of the Critérium du Dauphiné and the Tour de France after vanishing from these races for decades.

A challenging climb, almost traffic-free and with superb views from the summit. What’s not to like? Actually it’s hard work with few rewards along the way and a useful example of how the enjoyment of a climb depends on more than the road itself.

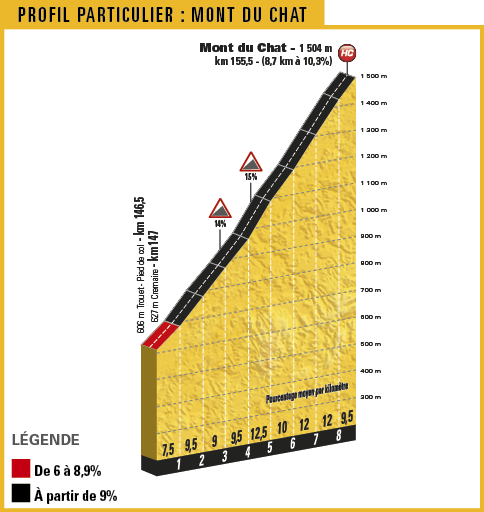

The Route: the Tour de France and the Critérium du Dauphiné will climb up the west side of the Mont du Chat taking the D42 just to the south of the hamlet of Trouet. This is 8.7km long and climbs to 1504m, a vertical gain of 905m with an average gradient of 10.5%.

- Don’t confuse it with the nearby Col du Chat, a helpful pass that allows you to cross the rocky ridge, the Mont is a different road to the top

The Feel: where’s the start? Unlike a typical mountain pass which climbs out of a glacial valley with an obvious beginning, here there’s a lattice of approach roads to chose from and they all rise up towards the official start so you’re climbing long before the climb proper. Take the “Tour route” and you’ve got three kilometres with plenty of 8% sections meaning hard work just to get there. The D42 junction is where you’d start your stopwatch or Strava segment and there’s no mistaking the junction with its sign for the Belvédère du Mont du Chat.

It starts oddly, for all the talk of a savage climb there’s a gentle start through the hamlet of Crémaire, look up at the mountain above and it the top doesn’t look far away. But after passing some farm buildings and fields you round a bend and see the road ahead rearing up in front of you, the gradient all too obvious visible. From here on it’s one long green tunnel, a strip of tarmac enclosed by beech, oak and later on pine forest. The canopy is so thick there’s rarely a view of the landscape below nor the summit above but it’s often shaded which helps on a hot day. With little to see you’re soon you’re reduced to a private battle with gravity that’s going to last 40 minutes or more and on a road that’s uncommonly steep, regularly at 12%, sometimes at 14%. There’s a brief flat section after 4km, a welcome surprise but it’s gone in 20 seconds and comes with a price, in order to make up the average the slope soars to 15% soon after.

Helpfully each kilometre is marked with a small sign to signal the altitude the average gradient for the upcoming kilometre and how far to go to the top; unhelpfully each one appears slowly. This feeling isn’t irrational, it gets steeper the longer you go on. The road is rough in places, not deteriorating but just made from a harsh surface which makes the battle harder still.

The gradient and its length makes it a tough climb, you may visit the region with Alpine gear ratios but chances are you’ll be bench-pressing your way up here and putting your back and arms into the effort. It’s reminiscent of the Mortirolo where you come geared for the Stelvio but have to leg-press your way up.

If there’s not much to see on the way up it’s very quiet and feels more likely that a deer or fox will appear than a car. Sometimes a cyclist flies down, Ag2r La Mondiale’s brown shorts were a surprisingly common sight around the area, the team’s HQ is nearby and they have plenty of supporters. Eventually you round a bend, spot the road levelling out ahead and there’s building ahead and excluding a small hunting or forestry shack earlier on it’s the first construction since leaving the barns at the start. If you’ve got any energy left use it up here because you’re about to reach the top.

If the weather is good be sure to stop at the top, there’s a special area to enjoy the amazing view across the Lac du Bourget and the Alps beyond. The severity of the ascent means the descent has its moments too, freewheel and your speed quickly picks up but the wooded nature means it’s always hard to see what’s coming so you keep having to back off.

The Verdict: the “travelling is better than arriving” concept doesn’t hold here. The defining feature is the severity, a hard climb where you may enjoy the challenge but there’s little reward during the climb such as scenery, sweeping hairpin bends or amazing vistas. You’re unlikely to stop and take photos along the way. It’s a contrast to the nearby Grand Colombier which offers severity with stunning views along the way that invite even the most ardent Strava fiend to pause and gaze at the Rhone valley and the Alps. The summit is the big reward, an achievement and a fine view that even the locals must enjoy again and again.

The Eastern Side: the Tour may go up the western side but more cyclists ride up the eastern side starting near the pretty Lac du Bourget, Strava suggests people log rides up the eastern side 2.5 times more often. This is the side rated by Le Cycle as one of France’s hardest climbs and they awarded it six stars, extremement difficile. It merits the rating being 13.5km long at an average of 9.4%. It’s harder but more rewarding, still a green tunnel but with some breaks you catch glimpses of the azure lake below along the way. The Tour will descend this but this is the recommended side to climb. Once again be sure to stop and enjoy the view at the top.

History: it’s only appeared once in the Tour de France. It was a second category climb in 1974 which sounds inexplicable. Back then the inflationary hors catégorie label did not exist and a climb’s rating owed more to its altitude than its difficulty. On the way up Raymond Poulidor attacked Eddy Merckx four kilometres from the summit and gained over a minute’s lead by the top. But the ageing Merckx relied on his descending skills and power, sprinting out of every corner, to bring back Poulidor and inevitably win the stage into Aix-Les-Bains on his way to winning his fifth Tour de France with Poulidor finishing second in Paris. It’s also featured in the Critérium du Dauphiné along the years, as recently as the 1980s and is the decider for the Classique des Alpes, an international race for juniors although they don’t climb all the way to the top.

Back in the days of Merckx and Poulidor this was a harder climb. Not that it was longer or steeper but because of the bikes used at the time. They were heavier but more significantly they didn’t have the range of gearing enjoyed by pros and amateurs alike today. Poulidor used a back-breaking 44×23.

Future: it’ll appear on Stage 9 of the Tour de France. It comes 25km from the finish which looks and sounds far, can it be decisive? The upper slopes of the climb are so hard and the descent is so steep that if anyone can escape then a chase will be hard to marshal until the final 10km of the stage and the final run into Chambéry.

France’s Mortirolo? they’re comparable but not the same. Both are steep and invite low gearing. The Chat’s road surface is rougher but the Mortirolo changes gradient more often. The Mortirolo is a Giro staple these days and has an obligatory Pantani memorial, the Chat has yet to be visited by today’s peloton.

Mont du Chat? Literally “cat’s mountain” it takes its name from the Dent du Chat, “the cat’s tooth”, a piercing outcrop of rock that resembles a pointed tooth. However debate rages about the origin of the name, it is the dental resemblance or is it from chas, an old world meaning a hollow or the eye of a needle, a crossing point over the mountain if you like.

Rock and role: this is the southern tip of the Jura mountains and technically not part of the Alps.

Travel and access: Aix-les-Bains sits below the mountain on the other side of the Lac du Bourget and has autoroute and TGV rail links while Chambéry is just a spin away too. Both make fine bases for Alpine riding with numerous other mountains and passes within reach (Grand Colombier, Revard, Chartreuse Trilogy and plenty more) as well as flatter valleys and large lakes to lap for easier rides.

More roads to ride at inrng.com/roads

Photo credit: summit view by Flickr’s Matteo Arrotta.

Amazing the TDF can miss a climb this big, why was left out so long?

Good question, there’s probably a mix of reasons as there’s nothing practical to stop the race, eg it’s not too narrow for the publicity caravan or a protected park. This is no ski station so it’s not been obvious or valuable as a summit finish and when the race has visited the area it’s gone elsewhere.

Also the Tour is a race of habit but recently Prudhomme and his team are searching for novelties, the Tour seems to be using the Jura mountains all of a sudden, see how it’s been climbing the Grand Colombier up the road too.

44 x 23. What, that’s insane!

He’ll have been on a triple, what was that, the middle ring, Inner Ring?

It sounds a bit of a cross-chain job by today’s standards but I salute the guy’s strength.

No, that’ll have been his lowest gear, it’s why all those black and white videos and even more recent ones from the 1980s have riders swaying as they climb, trying to force down the pedals or “pedalling with the ears” as it’s sometimes put.

As for Poulidor some claim he lost the 1964 Tour de France because of a gearing mix-up. He didn’t recon the Puy de Dôme climb ahead of the race, had the wrong gears for the summit finish and so struggled to take time on Anquetil (full story at: http://inrng.com/2013/09/roads-to-ride-puy-de-dome/)

44 X 23! When men were men and shorts were wool. I no longer ride the Mortirolo on our annual Legendary Climbs tour because it’s too steep (or is that I’m too old?) despite having a low gear of 30 X 29. Will the feats of the current riders with sub 7 kg plastic bikes and 34 X 32 (or lower?) gear ratios be looked upon with the same wonder and awe 50+ years from now?

To paraphrase: modern riders don’t have it any easier, they just climb faster.

I know what you mean Darren – as Greg LeMond used to say (something like) “Climbing hurts the same for everyone, some of us are just going faster” but I wonder if seeing video or photos of the likes of “Il Frullatore” (as the Italians call him) twiddling away, like a guy pushing a shopping cart while cradling a cell phone on his shoulder will affect cycling fans the same way as when “men were men…”?

Haha… as when “men were men”. Good stuff.

But c’mon, riders still pedal hard and none of the racers (men/women) are out on a Sunday coffee ride when they race.

No argument there CA, but the images are far, far, different from the “golden age” to nowadays with so many guys spinning away wildly on super low gears. To me it lacks something, but I wonder if in 50 years old-farts will be waxing on about the images of Froome at full cry on a steep climb? Many do just a couple of decades after Pantani, but for me it’s night and day when comparing him to the likes of “Il Frullatore”. The only other rider I can think of who was as ugly on the bike (but like Froome, surprisingly effective) was Fernando Escartin, nicknamed “The Crab”

http://www.velominati.com/evanescent-riders/riding-ugly-fernando-escartin/

A LONG TIME AGO, I used to do our local canyon on my 1980 Trek, 42 X 24. My knees don’t even know how I did that now.

How do you even get the pedals over the dead spots?

I suppose having decent fitness means you’re not going so slowly. I’d be at about 8kmh up there, which is a cadence on 44×23 of about 30(!). But I daresay Poulidor was going at 16kmh, maybe more, putting it at a much more reasonable 60.

Back in the 1990, I remember riding in the Alps with a 42×23. Of course, we avoided the too steep climb like la madeleine or le Galibier, but still we did les Saisies et le Cormet de Roselend.

It now sounds insane to me, but at that time I didn’t feel the gearing as inappropriate. Question of getting use to a pedalling style I guess…

For the foreseeable future I can only dream, ride vicariously in July – or if I can bring myself to buy one of those fancy new silent and smart trainers, ride as if I was there.

But the thought that struck me is probably too silly and stupid not to be shared: what if UCI made a rule to limit gear ranges to roughly those used “back in the day”? How would it change racing?

My simple hunch is that it would not only favour some types of rider while disfavouring some who are doing well now, but I’d imagine it would also necessitate some tactical changes.

An interesting suggestion!

My guess is it would have some unintended consequences. For one, it would blow people’s knees up and shorten careers.

Also, you are right, it would favour more powerful riders who can mash huge gears (Froome would be done).

AS CA says it could be bad for the knees or at least exaggerate any injuries. It’d require more core work, Raymond Poulidor used to say chopping logs with an axe over winter was good for his cycling which always sounded odd but thinking about it the action probably helped his back muscles. Maybe taller riders would be advantaged with their longer legs?

As it happens when researching this piece I came across archive video from the 1974 Tour de France and it features a journalist (Jean Leulliot, he ran Paris-Nice at the time) lamenting the modern gears and smooth roads of the era and how much harder it was back in the day when riders the road surface on a mountain pass was a “torrent of rocks”.

I recall reading somewhere that Froome has had knee trouble earlier in his career, which is probably why he spins the higher gearing.

I wonder what his gearing will be on this climb next Summer?

Yep, no matter what era it is/was these young whippersnappers always have it too easy compared to the old daze. Will they talk in 50+ years about how the cyclists used to get wet/cold when it rained or actually had to decide what gear to use on-their-own or were forced to control each wheel’s braking individually? I hope at least they’ll still have to pedal the damn things!!

Looks like Froome’s standard set-up is 52/38 with an 11 x 28 cassette.

I wonder if he will change this for Mont du Chat? It’ll be worth trying to have a peek for us, Inner Ring.

Even if he stays standard, 38 x 28 is no Poulidor!

52×38? Normally the choice is 50/34, 52/36, 53/39. Although I realise that the Pro’s do swap and change things about.

Be interested to hear the 52/38 confirmed.

52/38 is due to the Osymetric gearing. That is the equivalent of compact 50/34 on standard round rings.

Interesting! Back in the day more of the Classics riders seemed to be able to compete for GC at the Grand Tours? Was that because their power was more easily transferable when using bigger gears? So would that mean a slightly slimmed down Sagan could dominate? Or maybe a strong Classics/solid GC rider would suddenly come to the fore – Geraint Thomas? Or an all-round powerhouse like Dumoulin. I think it’d definitely be harder for the likes of Froome, Quintana, and Bardet to push those gears than some of the more naturally powerful riders. All speculation, obviously…

Or Tony Martin, Rohan Dennis etc etc.

That seems like an excellent supposition.

I would not favor “going back,” but certainly agree it’s interesting to think about how climbing has changed with the advent of smaller gears. Also interesting to ponder why it did not happen sooner. By the early 80’s mountain bikes were demonstrating the potential; on road bikes large gaps between gears was a real drawback, but as Colin Cox mentions parts of cycling culture seemed fundamentally opposed to the idea.

My dream luddite tech rule would be to ban time trial bikes. And obviously it is right that jersey sleeves are required.

First luddite priority has to be banning team radio and power meter head units.

I would be open to the compromise of allowing one-way radio transmissions from the riders to their team cars (like rider-to-pits radio in cyclocross) so they could still request service.

Stage 9, 25km out? Could be a classic finish if someone’s brave enough to go for it.

I’m dreaming, aren’t I? They’ll all be queued up behind Sky.

44 x 23 – I could do it in my sleep – or is that my dreams?

I remember my first road bike, a 1986 Trek 1500. It came stock with a 52/42 up front and a 6 speed 12-21 in back. I suffered with that for years until I snuck on a 23 hoping my friends didn’t notice.

Now at the age of 51 my low gear is a 34/32 and still sometimes looking for that lower gear.

But did it have Biopace rings? My 1988 Trek 1200 did, making that 42×23 that much harder.

LOL. We had the same bike. Being young and dumb I thought I was in heaven. And yes it had Biopace.

I did the west side of Mont du Chat on 39/26. It remains the hardest 9 kilometres that I’ve ever cycled. Got a 34/50 chainset very soon after. The view at the top is beautiful. I’d recommend Chambery as an excellent base for the area.

They recently improved the forest road N of the ridge from the Col de l’Epine. If you’re on an MTB you could certainly ride from there to the last pitch up to the Relais du Chat. The reason these roads are so quiet is the tunnel under le Mont du Chat. It’s all beautiful but don’t expect a view because of the trees.

And… take special note of the steepness of today’s stage on the descent. It really is a narrow, twisty, unpredictable and STEEP road, whichever side.

Some of us still have the old steel bikes with Campy Super Record 42/52 with Regina 5 speed freewheels

12-26 tooth. Thanks god they are up in the attic only taken out on rare occasions.

I felt your pain Larry, wool shorts in the rain and all.

Othersteve

Gulp.

Wish I hadn’t read this now.

We are coming over again this year and this will be our first stage and first climb we will be doing.

New bike, new gear ratio of 36/25 will be tough, but nice.

Great piece, thanks for the warning.

A hard first climb you’ve picked there. But hopefully the weather is good because the view at the top is great.