Do early wins matter? A lot aren’t on TV and plenty happen far from a sponsor’s target audience so the publicity value is often minimal. However it’s often said that a good start to the season sets up a team for the rest of the year, building confidence that in turn brings more wins. Similarly a poor start can burden a team for the year. Is this true? It’s possible to use data and statistical analysis to test this so let’s have a look.

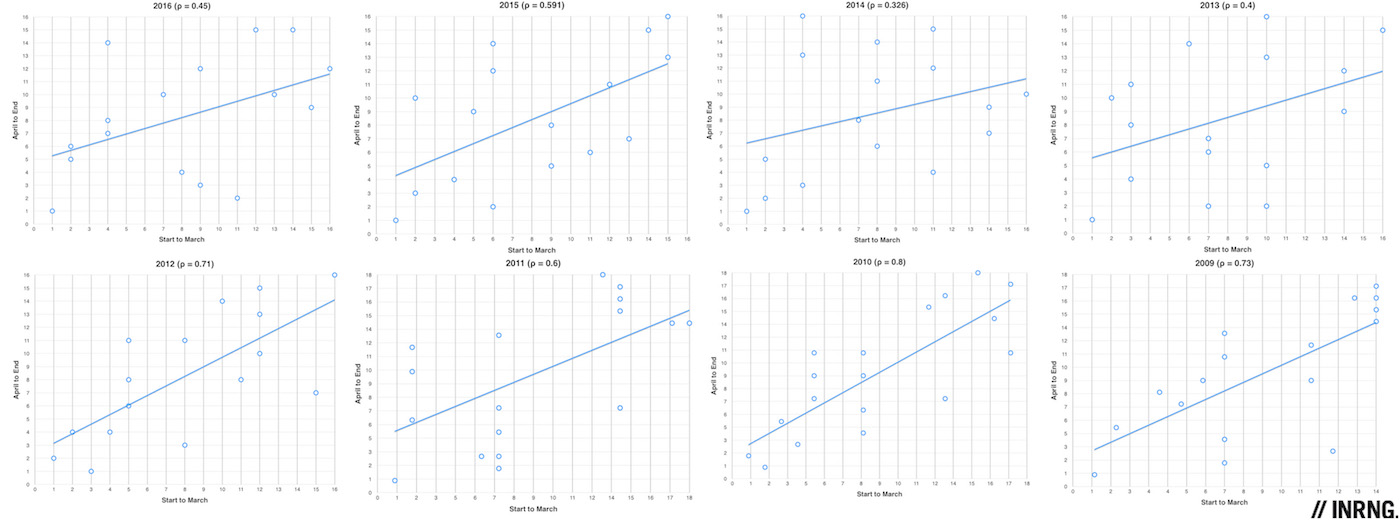

This topic was looked at early on last year but only looked at three seasons and when revisiting the data to add the outcome of the 2016 season it still made for a small data set. So the numbers for the past eight seasons have been crunched. How? All World Tour teams had their tally of early season success compared to the wins gained later in the year and these two data sets were checked for any correlation. As a proxy for early season results the cut-off was the end of March: count the race days and this marks almost precisely one quarter of the season’s race days. Here the rankings as scatter graphs for the eight years with the season start to March on the X-axis and April to October on the Y-axis in order to show the working:

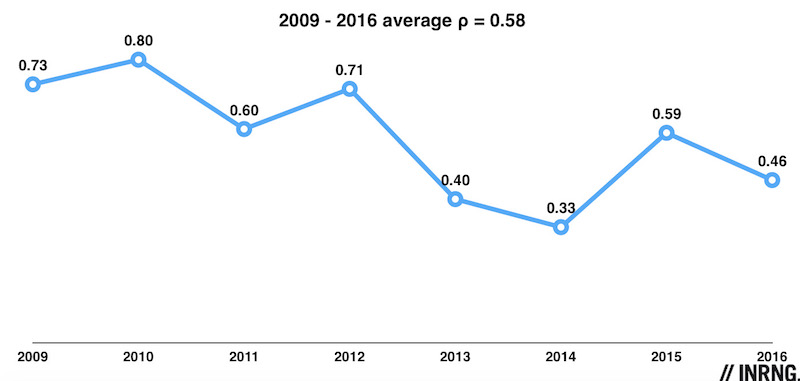

What does it mean? The data say the Spearman’s rho for the eight year period is 0.58 which is significant but not strong. Here’s the rho for each season:

As you can see the rho has fallen in recent years. It seems, at least going by the first years on the chart above, that early wins did help some teams keep going but this has dropped in recent years. The average still suggests a weak correlation.

In plain English please: early season success from January to March doesn’t correlate very well with the success rate from April onwards. A good start is nice but there’s not much momentum gained out of it; similarly a bad start needn’t be ruinous for a whole year.

Behind the data: when compiling the data it was obvious that some teams that get off to a winning start do just keep on going all year but not because they get on a roll, more because their roster is racked with riders who win often. The old Highroad team began the 2009 season with 13 wins in the period to the end of March, equal or more to the number of wins that several rival teams would enjoy across the entire season and this is largely because Mark Cavendish, André Greipel and Edvald Boasson Hagen rode for the team and remarkably ended the year as first, second and third in the table of individual winners that year. Similarly the team with the fewest wins all year often scores worst for the opening period too. The story of the data here is often one of mid-table shuffling where a team with a decent start can fade and vice versa.

Anecdote: To illustrate this the biggest swing observed was Ag2r La Mondiale in 2014. They’re a perennial low scorer in terms of wins but in 2014 they enjoyed a great start to with nine wins by the end of March including Carlos Betancur’s Paris-Nice success but only eight more for the rest of the year so their fine start was an aberration rather than the start of something.

In summary a winning team is going to enjoy a great start to the season regardless but those teams who take a few surprise wins early don’t tend to keep up the momentum and those teams without many wins by the end of March are not condemned to a dire season.

World Tour breakaway: one thing that the data don’t show is the changing focus of some teams and the overall increase in strength of the World Tour teams versus the rest during the period observed. Back in 2009 or 2010 it was common for the smaller Pro Conti teams to snap at the heels of the World Tour teams, or even bite chunks out of them. For example in 2009 the Pro Conti Androni team took 33 wins and several second tier teams collected plenty of wins to finish the year well ahead of the World Tour teams. Nowadays the World Tour teams tend to be grouped towards the top of the table leaving few crumbs for the lesser teams, to use an anecdote to illustrate this no wildcard invitees to the Tour de France has won a stage since 2012 when it was frequent before this.

If the data suggest early wins don’t bring momentum then the broader question is whether early wins count for anything more than morale and narratives. It’s questionable whether they bring publicity as quantity and quality are not the same. We might think the goal of a team is to win but really it’s to promote their sponsors and if winning the best way to do this, not all wins are equal. Take an un-televised race with a handful of spectators at the finish line where the results end up buried in a local newspaper and yes, you have a win in statistical terms but the value to the sponsors is minimal. Teams want to win but they’re often measured against expectations rather than victory rankings, Team Sky’s big budget and blue chip corporate sponsorship means they have to win the big races that are on TV in the UK, Italy and Germany because these are the key markets for the sponsor. Put simply Sky needs to win the Tour de France. Meanwhile sales of lottery tickets and scratchcards in France won’t change if FDJ storm the Tour Down Under but a win in the GP La Marseillaise does help the sponsor push its brand in the provinces so each team has its own subtle objectives.

Conclusion

Does a team that starts winning early carry on winning throughout the year? In a word “no” say the data sets mentioned above when tested.

There’s a more nuanced story here though, the answer is “yes” for a team like Quick Step today or HTC-Highroad from the past where wins seem to come easy any month of the year and just as weak teams from the past like Euskaltel or Vacansoleil struggled all the time. But it’s outside of these anecdotes that the data debunks the the hypothesis of a good start leading to a good season.

“We might think the goal of a team is to win but really it’s to promote their sponsors and if winning the best way to do this, not all wins are equal.”

Indeed. But the goal of the individual athlete is to win, and promoting the sponsor comes second. They are mercenaries. But in any case, for the athletes too not all wins are equal and certain races carry more clout.

…”for the athletes too not all wins are equal and certain races carry more clout”.

I couldn’t but smile thinking about this tweet:

https://twitter.com/Perfilatore/status/830377344187654144/photo/1

By the way, huge victory by Valverde in his home race ^__^ …once again…

PCS photo of the day:

https://twitter.com/ProCyclingStats/status/830542925444558849/photo/1

I predict Cannondale’s poor start (no podium so far) will prove a good indicator of their year.

One way to predict future performance is to look at past performance and the team had a poor season last year. They have a house sprinter in Wouter Wippert but he’s not won since 2015. In doing the data tables for this piece the team finished 3rd among the World Tour teams in the 2009 season with 29 wins.

I’m not sure if WW has been fighting injuries or such, but he’s been far from what you call a sprinter the past year or so. Not even getting in top-10 on sprint stages.

“not all wins are equal. Take an un-televised race with a handful of spectators at the finish line where the results end up buried in a local newspaper and yes, you have a win in statistical terms but the value to the sponsors is minimal.”

Sky would get more domestic column inches from, say, Geraint Thomas winning the Tour of Britain or Tour of Yorkshire, than if he won Flanders or Roubaix. Daft, but it’s a confusing sport to the uninitiated.

I would think even more so now, early season races reflect differing goals for teams. Guys flying in January at TdU will have how many training valleys and peaks before (IMHO) the races that really count? I laugh at the headlines reading “Rider X Serves Notice for LeTour” about a result in January, the same as those which write another guy’s entire season off based on what used to be just training events. The only thing we can count on is the classics riders will try like hell to be in their best shape during those races while the GT riders focus on stage races later in the season. The rest of it is just something-to-do until the real racing starts. How many days until MSR?

Yeah, everything before Omloop has a preseason feel to me, even if I do get pulled into watching them. From next week though there’s a great run of races and it feels like the season has started – Omloop, Strade Bianche, P-N and T-A then finally MSR. Can’t wait!

And there’s 34 days til MSR, not including today…

No guarantee’s, but theres nothing wrong with bagging some early season wins. A wins a win as they say.

Great work as always. Although far more data intensive, it’d be interesting to see how this stacks up for individuals. For grand tour riders, it probably never amounts to anything but for the classics riders, early wins usually show they’re on the right track (anecdotally).

Is there much variety between the different teams? i.e., are there team for whom a bad/good start generally foretells a bad/good season, and ones for whom it’s generally irrelevant? Or are they all much of a muchness?

Apart from the examples cited in the piece it’s hard to pin down a team, especially as many have changed over the years, for example Team Sky had a lot of wins in 2012 because they’d signed Mark Cavendish but today sprinting for them is less of an important goal; or we can compare Lotto-Jumbo today which is a lower budget team to its predecessor Rabobank which had more wins but spent more money too.

This analysis is terribly lacking. The correlation between early-season wins and later wins is due to a large combination of factors: team strength probably being the largest causal factor. Trying to infer anything casual from this correlation is meaningless and a more advanced analysis is needed. I realize none of the claims above were made very strongly but the statistics were still given a bit of significance which is unwarranted.

I wonder why the correlation has been dropping? Not knowing much about the history of cycling, could increasing specialization mean the teams that win early (e.g. EQS) go on to win less with other teams focused on later-season races (e.g. Sky, Astana) then winning more?

You’re right it’s a simple analysis but many, including team management, can still see early wins as something vital for the rest of the season. Team strength was touched on above, it does play a big part with the top and bottom two teams but the mid-table teams move up and down.

I think specialisation does play a part, there are teams that really only get going once the snow melts in Europe, like Astana and Katusha as well as the now defunct Tinkoff/Saxo team often struggled for wins until April or later.

I have noticed a trend in INRNGs excellent statistical analysis over the past few years which I suggest is somewhat flawed in its conclusions.

It is NOT simply the number of wins which dictate the most successful team, nor should wins be used to predict a teams potential performance. It has everything to do with the QUALITY of the victories. Not so long ago the importance of a win in certain events was fairly easily identified, understood and assessed. The UCI have contrived to distribute WT events to races hardly worthy of the name in a sporting sense, and thereby muddied the field.

If we must try to model bike races, at least we should try and assign some weighting to the relative importance of races.

But that’s what the usual rankings are about, no? It’d be harder to measure whether early gains bring big gains all year because the season’s rankings are so weighted to the grand tours and especially the Tour.

INRNG. I take your point about GTs, but they have simply become a financial red herring. Statistics in something as uncertain as bike racing is always going to be a big ask. I am trying to be constructively critical.

There is no reason in the world why one day events should not stand alone and carry a weighting due to their status, history and parcours. The classic one day races have certainly been devalued in favour of the Grand Tours, as have a couple of the more recent incarnations, but they often provide far more sporting suspense in their condensed time frame. It is interesting to note that there are many one day races which gain little publicity but have a sporting value way above their current status. I suggest that three week races are now so different in nature to one day classics in their modern form, that to try and correlate the two has now become all but meaningless.

Let the one day races stand alone, and then apply a weighting based on their sporting value. I don’t subscribe to using UCI rankings to classify a race, they are increasingly being influenced by finance and not sporting value.

Plus, inrng did mention that different teams target different races

Yes, the analysis could be considered crude but cycling is such a dynamic sport with different aims and objectives, that it could be spun many ways!

One angle could be: do worthless wins lead to famous ones? Huge time required to compile the data set and it’d be easy to get bogged down on the best way to weight / rank the events.

As INRNG already said though, how do you weight victories in relation to local markets? A win for Wout Poels in LBL is huge for him, significant for the cycling fans who follow this blog, but hardly registered in Sky’s UK market. But if Thomas had sneaked last year’s London/Surrey “Classic” it would’ve secured significant UK coverage. We all know which is better in sporting terms of course but similar dynamics will exist for other sponsors, especially in newer cycling countries. The early calendar is obviously very important to Orica BE, and understably so, but I don’t know how you could rank that. Ditto the likes of La Samyn will rank above many WT races for Quick Step etc etc.

ahh the days when young Eddie Boss won regularly and folks were saying he could do it all, talking about ‘the next Merckx’ etc…

I’d be interested to see a compilation of how many unique riders each WT used over the three GT events for a year.

Do stronger teams use more or less different riders, or are they in the middle with lesser teams at the extremes?

Obviously the maximum would be 27 unique riders for a team where no-one doubled up.

Cycling is so objective as to what each “big” race – big as considered by fans of cycling rather than the general TV sport watcher – means to each rider/team/organiser that it’s difficult to measure whether or not early wins means year long success. Inrng has outlined the compilation of some data, which once again achieves the objective, which is to make interesting reading for those keen on cycling.

Interesting article but what does rho stand for?

It’s a measure of correlation, the full explainer at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spearman's_rank_correlation_coefficient

The short version is you take two sets of data and then compare them, so you rank the teams on wins from January to the end of March in one column and then from April to the end of the year in the next column and then you compare the change in the rankings, eg who moved up or down and using a formula you get the rho or ρ, always a value between -1 and 1 where 1 means a perfect association, -1 means a perfect inverse association and zero means no correlation at all.

Thanks for the explanation.

So, why do people think the Pro-Continental teams have become compartively weaker than the WorldTour teams in recent years? And what could be done about it? (I’m assuming a relatively stronger second tier would be desirable to most.)

Is it simply and solely down to the wealth gap between them being bigger these days?

“Wealth gap” and “cycling team” don’t belong in same sentence… even the world’s “richest” team, Team Sky doesn’t actually have any equity (aka “wealth”) in the team…

History’s most financially successful cycling team structure is currently being sued for up to $100M USD, haha.

Ok, Inrng – sorry, I know completely off topic. I couldn’t help it.

Great work INRNG, how detailed is the dataset? I’d be interested to know whether it makes more difference to a sprinter than a GC / Rouleur if that is something that can be looked at.