“Pantani, Debunking The Murder Myth” by Andrea Rossini, translated by Matt Rendell

The Giro finishes in Madonna di Campiglio today. While we’re all interested in the climb to the finish this is the tale Marco Pantani’s fall from grace which began here, taking him from a national icon to an isolated crack addict found dead in a hotel.

In the 1999 Giro d’Italia Pantani was leading the race with just one mountain stage remaining, a coronation for Italy’s most popular sportsman, but a pre-stage haematocrit test scored 52%, his blood was too thick and he was ejected from the race. The rise and fall of Pantani is expertly told in The Death of Marco Pantani by Matt Rendell. “Pantani, Debunking The Murder Myth” isn’t so much Pantani’s freefall but the moment of his collision with the ground.

Pantani’s death stunned Italy and he is far from forgotten. There are probably more Pantani monuments in Italy than Coppi ones. If his exploits on the bike are celebrated, his death is still a subject of intrigue. “Pantani was murdered” ran the front page headline of La Gazzetta Dello Sport last August but the quotation marks bracketing the words are as important as the name and verb, a quote rather than a statement. The newspaper gave front page prominence but the story was all over the Italian media, especially television:

“Ten years ago, he was found dead in a hotel room. It was said immediately, and repeated for ten very long years, that he died of an overdose. Today, however, another, compelling, truth is emerging, and perhaps we can say that he was murdered”

– Quarto Grado, Gianluigi Nuzzi, Rette Quattro

“The official theory about the death of Pantani is creaking more and more, as the hurricane of new evidence continues to blow in a totally different direction”

– Davide de Zan, Tiki Taka, Italia Uno

“All the dailies, all of them, are talking about a conspiracy. Even the investigating magistrates believe there was a conspiracy”

– Barbera D’Urso, Domenica Live, Canale 5

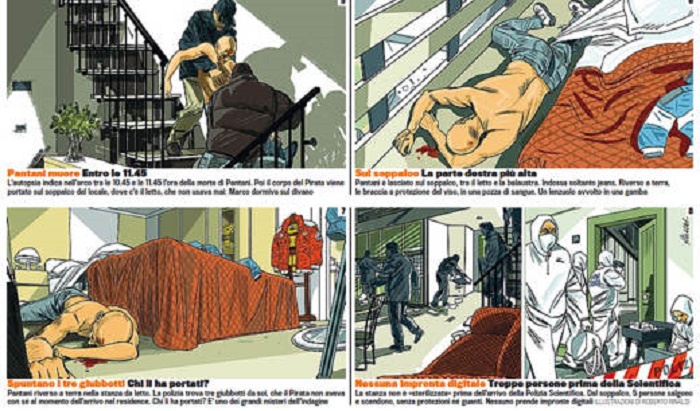

While the inquest was being opened again the media seemed to have made up their minds, happy to stir up an exciting story and bash Italy’s creaking legal and judicial system. Aided by celebrity lawyer Antonio De Rensis sunbathing in the limelight, Pantani’s family revived conspiracy theories concerning the death in the Hotel Le Rose in Rimini. La Gazzetta even printed cartoon capers of what could have happened.

Nobody wants to believe in suicide or overdose, psychologically it’s easier to imagine nefarious criminals rather than dwell on a champion reduced to addiction and isolation. Conspiracy beats logic. Take the fact that Pantani had barricaded himself in the hotel room. As Rendell writes in the introduction speculation got ahead of reason:

“the simple fact that the door was locked and barricaded from the inside, and the windows were shut from the inside and the blinds drawn, has been largely ignored. One well-known Italian sports writer even commented, “Locked from the inside? But that’s the classic crime story scenario,” thus transforming evidence against the murder theory into proof that it was true”

This book is a response designed to counter all the claims of murder and conspiracy. Andrea Rossini is a local law reporter and has covered the Pantani case since the moment news of his death arrived. The original title of “Delitto Pantani: ultimo chilometro (segreti e bugie)” translates as “The Pantani Crime: Last Kilometre (Secrets and Lies)” but the English title makes the book’s mission clearer.

The book has an introduction by Matt Rendell to set the scene and then two parts: Part One is a meticulous reconstruction of the last eight months of Pantani’s life, “every episode, every description, every snatch of dialogue derives directly from a witness statement or a scientific report” writes Rendell. Part Two is shorter and the “rebuttal” section, providing the explanations to many of the doubts that have been raised by the murder theorists.

The book suggests Pantani’s final trajectory is inevitable, that he had a habit of barricading himself into rooms and consuming huge quantities of crack cocaine, amounts that would have killed others before but Pantani’s oxen heart could just about tolerate. This is Pantani on 27 December 2003 in a hotel in Miramare:

The door was locked. The room was very hot. The room was in chaos. There were empty cans and a candle in a bottle. There was white powder everywhere…

…He was smoking [cocaine], sniffing it, burning it, reducing it to resin or oil and putting the drops in his nostrils. He was eating it. Another physique would have collapsed.

This was a scene that had apparently been repeated five times before, the binges were happening again and again and he’d almost died once before. His friends and family had tried to help again and again but Pantani’s unwillingness to embrace rehab was leaving them frustrated, trying their patience and by the time Pantani was alone in Rimini is friends were fatigued and his parents were touring around Greece. On the last occasion in Rimini he had also taken prescription medicine which could have been the final excess.

Some of the claims behind Pantani’s murder are bizarre. Take the “chinese food” hypothesis where there’s a note of a “Chinese food container” found in the room. Since Pantani disliked Chinese food this was used to suggest someone else had been inside the room. Only the container is simply an aluminium box, described once in a throwaway line as “for Chinese food” but in reality the kind any type of takeaway food is delivered in and it turns out an omelette had been delivered to Pantani’s room from a nearby restaurant before his death. This is just one example but the book dismantles many “Chinese whispers” that have spread across Italy.

The Verdict

This isn’t a cycling book, there’s no inside account of Pantani’s racing career. It’s a tale of drug abuse and addiction followed by post mortem medical analysis and crime scene reporting. At times it’s uncomfortable as the delivery of facts is relentless and as much as the book tries to stress there was nobody else in Pantani’s room it’s as if you’re locked in there with him.

Another book cashing in on Pantani? No, this is not a glossy tome found in bookshops, supermarkets and tobacconists across Italy, it was rejected by major publishers and Andrea Rossini did not get tour the TV studios in the name of marketing. As Rendell adds to the book “commercially, Andrea Rossini’s book Pantani: Debunking the Murder Myth was a disaster: only if his death could be made out to be murder was there a story to sell”.

It won’t stop the moral confusion over Pantani the cyclist, the champion, the doper, the drug addict but it is a calm exposition of the excesses of coverage of Marco Pantani, rebutting the tall stories and setting some records straight. If you’ve read The Death of Marco Pantani this is a compelling epilogue.

A copy of this book was sent for review. You can find the English version as an e-book only for the Kindle device with online retailer Amazon for $6.25 or £4.79. The Italian version exists in paperback for €10.

More book reviews at inrng.com/books.

The life and death of Pantani illustrates only too well, the dangers of sportsman thinking that what they might do in their sporting life, is somehow normal. Pantani is probably the ultimate example. There have been far too many more, household and non household names, who’s lives have been blighted, ruined or ended by their sporting experience.

A lesson for all who don’t accept that doping in our sport constitutes more than just a moral hazard.

You wouldn’t believe, but I’d endorse every single word you’ve written above. Maybe not every implication, but, as it is, I found it perfect. When just you and Larry had written something on the subject, the two comments looked so adequate I decided not to add anything. Then the magic was broken and the hell’s gates were open for my posts 🙂

I would like just to specify a couple of things: first, it seems there’s not such a strong correlation between doping and psychoactive drug addiction (long debate on the subject that I won’t quote here, take it as an “opinion”, if you like). Whereas apparently there’s a significant correlation between top-level sport and depression. And there you have the link to other issues. As I said, this is in no contrast with what you wrote.

Second, even if Pantani could have had a peculiar sensibility, and even if his *social environment* outside cycling wasn’t the best you could imagine, still cycling’s world responsibility (including but not limited to related media) is huge. I won’t enter in details, but it’s not like Pantani had a pathological personality (the myth of the especially “fragile” character), as much as that he happened to live in a pathogenic context.

Besides that, as a separate and very collateral reflection, I often think… imagine how it was to live and ride in the first part of the 2000s years, like knowing or having a strong guess about what was happening around Armstrong and all (fans *knew* or guessed pretty well, imagine an insider!), while at the same time reading in the newspapers that you’re the greatest “dopato” in the sports world, the last rotten apple which bloomed on the now-forgotten ill-tree of the Nineties. Being rejected by the Tour, with its post-dated prescription and Actovegin: ans, between the lines, they say it’s because of your doping past! (…while maybe it’s because Lance got scared along the way to the Joux Plan 🙂 ). Not saying this justifies anything, or that it’s anyway worse than being forced to quit cycling because you don’t want to dope has it happened to many, still it’s a very disturbing perspective.

I read Rendell’s book but didn’t really see this thing as a “compelling epilogue” so I didn’t bother. Rendell makes his point pretty clearly in his original and very thorough account, though I think it’s wide-of-the- mark. I suggest adding Manuela Ronchi’s Man on the Run (which is off-the-mark in the other direction) to better understand this sad story. I find it a shame that so many English-speakers see Il Pirata as little more than a doped-up foil to BigTex. Italians venerate the man in the same way an earlier generation venerated Fausto Coppi. It’s likely both of them used doping products, but what people venerate and celebrate was that both of these men were victims of accidents/crashes throughout their careers in addition to passing away early under complicated circumstances. Despite those accidents and injuries, they climbed out of hospital beds to race (and win) again. I don’t know of any doping product that can inspire this…the passion to rise up and try again despite very tough odds. I believe this is the reason monuments are erected to these champions in so many places in Italy. W Coppi! W Pantani! W Il Giro!

Larry, I appreciate your sympathies and your opinion on most post but!

Armstrong picked himself up out of a hospital bed to be a cycling champion who doped.

I’m no LA fan but they were both cheaters, perhaps the NFL player Junior Seau might be a better fallen national champion who has a similar gravitas.

Sorry Larry, reread your post I agree and humbly provide a retraction.

I’m puzzled by the small number of comments this story has generated. Pantani stories usually get dozens of comments as people either idolise him or detest him as a cheat, but for some reason people aren’t reacting to this.

The book’s not about that, by the sounds of it; it’s about the very sad but nonconspiratorial manner of his death.

The whole subject is too complex and the fact that doping is involved blinds people. Pantani had serious problems that had nothing to do with sport or doping, although those two things of course added to his problems and made it harder and harder to get the help he would have needed. In the end too many people cared for the champion and not for the man. And that is why the one still lives on while the other doesn’t.

Well said

I am personally a little tired of Pantani stories. In my mind, he represents the darkest era of cycling (although it was the flashiest on TV). Armstrong, Festina, Jiménez, Vandenbroucke, Gaumont, Rodolfo Massi, peroxydized hair, multicoloured shorts, transformed performances, outrageous sunglasses. A generation of riders that seemed to belong more in an after-hours techno disco inside some abandoned decrepit factory than drinking beer or wine in a village café. Previous generations always had excentric side, sometimes even sordid. But Pantani’s one was sordid and vulgar at the same time. I’d rather read about Freddy Maertens’ or Johan Van der Velde’s craziness and excesses, and the society they represented, than about Pantani end-of-millenium period.

I guess Pantani was before many peoples interest in the “new” sport of cycling. Yes a controversial figure and I prefer to refrain from judging his methods as I cannot honestly say how I would have been in his position.

Everything I have ever heard about Pantani and his death suggests that he died of a drug overdose. I hear these stories of a murder investigation and wait for some amazing evidence to suggest otherwise but nothing arises. That we are even talking about this says everything about Italian society and their belief in conspiracy theories. Some people just can’t let go of the Pantani myth.

That’s maybe because Italian society has witnessed a good deal of conspiracies along the last decades, and most of them are now reported as such in history books, that is, they aren’t just *theories* anymore.

Which doesn’t mean that every conspiracy theory makes sense, but we should also consider that a part of the hostility raised against *conspiracy theories* (an attitude legitimately provoked by the most absurd of them which are spread through the internet) often smells like a campaign against critical thinking. The call for “factual realism” reduces itself to believing official versions and far-from-disinterested big media sources, or, even worst, to the dim reproduction of commonplace thinking which, in most cases, is perfectly able to overcome and erase established facts.

I’d stress that all this isn’t necessarily referred to BarkingOwl nor to Pantani’s death, just a general reflection.

I think that Italy also suffers a feeling of national guilt towards its “most popular sportsman” after letting him die the way he did so shortly after hailing him as their greatest hero.

It probably provides some sort of consolation to think he was the improbable victim of some mafia-style vendetta rather than the cold truth of an entire country turning its back on the athlete once praised.

Partly true, but a significant part of Italian fans never let Pantani down. Whereas the media attacked him relentlessly and without pity.

Without decency, I’d say (I could quote specific newspapers pages).

And most of them aren’t feeling guilty at all. They’re just cynically trying to exploit just another episode of the saga. Just as they tried to buy fans back with the hypocritical and uncritical celebration when time had come.

Obviously, lots of people just follow the media wave. But some people, a surprisingly relevant number, resisted to the *truth* they were being sold, which included “in the bundle”, among other things, that cycling was the sport where doping was to be found and that doping athletes, like Pantani, were isolated rotten apples and not part of a more vast panorama.

I haven’t got the slightest idea about what eventually happened to Pantani that night. Still I think that the investigation has so many flaws and strange elements that a revision was due. I could provide a checklist to see if the book covers them all, but it’s not a funny game.

Rossini wouldn’t agree about that point above but, as I’ll explain in a few lines time, that’s a weakness of his book, not an element on its favour.

We tend to believe that those who “debunk a myth” offer the ultimate truth, but something like that is simply out of reach in most cases. That’s the tragedy of history. In most cases we are left to compare different perspectives, not “the truth” with “a myth”.

I’m not very convinced by what inrng reports of the book, but I haven’t read it, hence I won’t criticise it in every detail. Note that I think I share a good deal of the book’s perspective, that is, I’m no fervent defender of the murder theory, even if every clue in that directions should be duly examinated.

The problem is that Rossini’s daily work depends on the institutions whose actions should have been put under scrutiny by any serious analysis about Pantani’s death. He was publishing articles, those same days, thanks to what the police and the attorney’s office was passing him. He’s still working with them now… He can probably offer good insights about a lot of little details, but most of his main primary sources aren’t that reliable. They won’t go around saying they did it wrong. Quite the contrary, they’ll try to underline every piece of information that can justify their attitude at the time.

Nor is it true that the book didn’t receive its portion of limelight in Italy. I guess that inrng got the info on that about the book itself or the English publisher. Well, they’re building up a little myth themselves.

In spite of the hypocritical collective celebration, Italian society is quite divided on the subject, and Rossini’s book got his good share of theatre presentation (something uncommon in Italy) and positive reviews in the main daily newspapers, like Repubblica or Il Giornale, as well as in a very important online newspaper (Il Post), or from the monthly sport magazine Il Guerin Sportivo, then TVs, radios…

From what I read here, I suspect it wasn’t published by major publishing houses because it couldn’t always pass the “fact checking” procedure that that kind of companies put in place for a book like this. For example, the quote inrng reports about Pantani’s abuse of cocain comes from one of his doctor’s declarations, but it was originally hypothetical. I don’t know if it was Rendell (whose book has a number of problems, too) while translating it, but various “forse” [“maybe”] uttered by the doctor have been lost along the process.

All in all, as I said before, it’s probably a very good book to read if you’re interested in summing up more different perspectives about Pantani’s death, at least if you’re very interested in *that* aspect, not to be extended to the rest of his life: note that in June 2013 Pantani was indeed recovered in a rehab… and the book (not so casually) focuses on the *last eight months* of Pantani’s life. We should be very careful when projecting that image over the preceeding years, even if the addiction was already there.

More than everything, as I said, this should be read, as any other book, with a good dosis of critical sense, that is, taking into account where does every little piece of information come from. An alternative proposal, that’s all, as biased as others (ore even more I’d say), but with the possibility to provide more exact details on some points.

Fact check, Gabriele: Since Pantani died in 2004, I’m not sure how he could be “recovered in a rehab” in June 2013. Typo, perhaps?

Ahahahahah, nicely spotted! 😉

You never know, but it was 2003, indeed.

I read that book a few months ago and have to say it left no big impression. It is partly the title: “debunking” makes you think about proofing things. Showing something definite. This wasn’t the case. So a different title would have helped. Because it is still a question of believing. And I am not sure about the motivation of it all. If you are so involved into a story, it is hard to tell apart where it isn’t about that anymore and when it becomes a personal story and is better told as such. If you live in Italy and followed the daily media flow, it may feel different, it may feel like a necessary, important book. But not living in Italy I didn’t feel the necessity to settle this special score.

There is a lot of the conditional, the “forse” or the “yes, but” as Rendell puts it. It’s hard to know the truth and Rendell seems increasingly convinced the prescription medicines were the cause of death. But it does shoot down some of the wilder tales as much as Rossini relies on the sometimes weak institutions of the judiciary it is probably more solid than TV channels chasing ratings and latching onto the wilder claims about murder and how this could have happened. For this the book is a good counter.

No doubt that most of the media campaign (TVs & websites & Gazzetta, too) we saw from last summer on was simply revolting.

It was a real pain: on one hand, people felt the need to get some attention back on the subject in the hope to clarify a huge quantity of discomforting elements which had just been silenced, both about Pantani’s death and Campiglio’s blood test; on the other hand, many felt that if the price to be paid was the media vultures flying circles above once again, it was too disgusting to be endured.

I didn’t mean to dismiss the book, just advising to take care with it. It’s not like the ultimate factual truth about Pantani’s death, nor is it a picture of his life after Campiglio. If anything, of the last months’ downward spirale.

In Italy (?), you’ve got to be very careful both with conspiracy theories and with the *official* versions.

However, I acknowledge, totally, that gathering different sources, with different POVs and interests, is paramount, that’s why I myself agreed on suggesting the book (without having read it o__O) to whoever has a specific curiosity for the subject.

It’s a common trait in Italian society to look somewhere else to blame, there’s always a “dark force” at work. Worth considering all of this in that context and the broader context of Italian society. Pantani represented the working boy made good, the outsider only to be victimized by the figures of Italian authority (if you need to cheat a little to beat they system, bravo, well done you have furbi (cunning would be a loose translation)). It’s a sad reflection on peoples desire to see Pantani in that light that this book needed to be written, but then you only have to look at Martinelli’s recent comments to realise that many people in position of responsibility in this sorry tale do not wish to recognise the truth or their part in a tragic life

Yeah, no “dark forces” at work around the world, rise and shine! ^__^

“Working boy made good”? Nothing further from the public (and private) image of Pantani. You can see that from any weepy television drama about him. Not even there they call for “working class” values.

“You have furbi” makes no sense, maybe you meant “you are furbo”.

It’s amusing when people try to speak of something they don’t know nor understand at all, starting with “It’s a common trait in Italian society…”: you’d expect some Lévi-Strauss (not the denim, you know) writing something like that, but, alas, he’s dead, hence we must content with Anon’s insights.

Pantani was riding just about when I really got interested in cycling and as such I’ve ended up with mixed feelings about him. Watching him fly up the mountains was quite possibly the greatest thing I’ve ever seen in sport. I wanted to be him, to ride like him, I wanted his bike, Italian style and that elusive thing “panache’. Now after what happened and what came out about that period I don’t know what to think. I won’t judge the man for what happened, he obviously had demons in his life that he just couldn’t deal with and no-one can know what that is like unless they have been through it. I also won’t judge him for the doping, it was as much a part of cycling as turning the pedals was in that era and I don’t think anyone can truly say what they would have done in his shoes. I’m not naive enough to believe in the new “clean-era” of cycling when you look at who is still involved and the number of new riders still getting caught doping and I know that most other sports are no doubt just as rife with doping as cycling is, so I can split my appreciation of the sport from my views on doping fairly well.

Pantani will always be one of my favourite riders. What happened is incredibly sad but he deserves to be remembered for what he did on a bike.