Having covered how points are calculated using the UCI’s secret rankings the other day, now it is time to see how these points are used in conjunction with other criteria to award a licence to a team. Because once the teams are ranked in order of their sporting value there are more steps to follow before the squad qualifies for the World Tour and its prestigious calendar of races.

The first 15 teams pass the sporting test but teams ranked 16th-20th are subject to a review to determine their position in the top-18. This year the UCI is deciding between 16th placed Argos-Shimano, 17th Lotto-Belisol, FDJ in 18th, Europcar in 19th and 20th ranked Team Saxo-Tinkoff for the remaining three places. We can delete Europcar from the list because the French squad does not want a licence with the obligation to ride three grand tours, its squad is not deep enough. So we have four teams racing for three places. What determines this? The UCI rulebook explains:

2.15.011b …the licence commission will inter alia ascertain whether there is a clear gap in the classification or whether particular circumstances have had an effect on the team’s results. Such particular circumstances shall include any injuries to riders, the types of event which the team has ridden and the homogeneity of the team.

This is sensible in that a subjective analysis helps in awarding the final places. The trouble is making the decision, who to promote and who to demote. Teams are invited to the process and can make representations to the UCI’s Licence Commission, a group composed of four UCI staff (Paolo Franz, Hans Hoehener, André Hurter, Pierre Zappelli – all Swiss). However there are three more criteria to guide the decision:

Financial: the team has to submit financial information like funding sources, any bank balances and the forecast outgoings for the year. All these are assessed by an independent auditor. If a team has been up and running then audited accounts for the previous year have to be submitted as well as interim accounts with more recent data as well as forecasts for the upcoming year right down to monthly budgeting and the business plan for the duration of the licence.

The idea here is that only teams with funding for the full year ahead can get a licence, to prevent unpaid wages and a team limping into financial limbo.

Administrative: this relates to all the paperwork that accompanies the application for a licence. A range of documents has to be submitted and the UCI’s Licence Commission looks for compliance of the application with the rules to ensure a complete folder and even notes teams for the “professionalism and rapidity with which this documentation is assembled, and respect for deadlines.”

Ethical: it’s worth sharing the UCI rule in full for clarity:

The ethical criterion takes account inter alia of the respect by the team or its members for:

a) the UCI regulations, inter alia as regards anti-doping, sporting conduct and the image of cycling;

b) its contractual obligations;

c) its legal obligations, particularly as regards payment of taxes, social security and keeping

accounts;

d) the principles of transparency and good faith.

This might be the most contentious point but note it is still an absolute test. It is not about opinions or hearsay but has to rely on proven evidence.

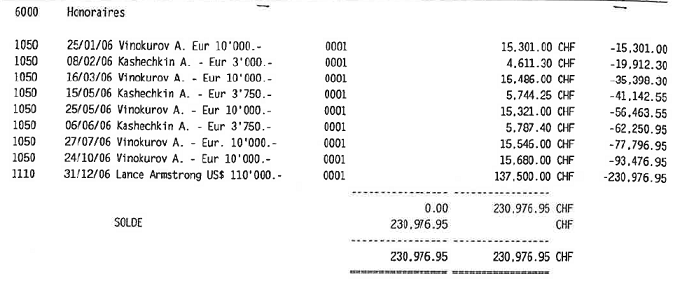

For example some readers might raise their eyebrows at Astana getting a team licence given Vinokourov has been linked to Doctor Ferrari but the example is useful. For now he might be named but there is nothing more. The UCI could and probably should investigate but being named in a document or a newspaper is not enough, a conviction or at least overwhelming evidence is needed otherwise the team could call the Court of Arbitration for Sport and insist on the presumption of innocence. This matters because the process has to be firm but fair and the last thing we want is teams being ejected because the UCI doesn’t like the team and starts rejecting some teams because of bias and preference.

- Note there is a general test applied to all team staff in the sport on their past, the new rule was introduced to ban staff with a past of doping from working in the sport, from managers to doctors, mechanics to rider agent. However an ex-doper can get back into the sport if they were caught only once, if the ban was not for two or more tears and if five years have passed since they were caught.

But this means it can be hard to review the teams, perhaps the financial criteria and auditors can detect things but it was not that long ago that the Russian mafia created a cycling team as a money-laundering front.

Distance

The Licence Commission is part of the UCI but the work is done separately, the idea is the commission gets on with the job rather than having the UCI and its road race staff run the process. How far the separation actually is remains to be seen.

Licence suspension and withdrawal

A licence can be granted for four years but is conditional on meeting the sporting, admin, financial and ethical criteria each year. As said the other day this makes the licence more an option for four years rather than a certainty, especially as the sporting rankings move up and down. But the ethical, admin and financial points matter too and if the UCI has been misled or if the facts change then the licence can be withdrawn.

Who holds the licence?

A “paying agent” normally holds the licence and this can be an individual team owner, it could be a company set up to run the team and rent out space on the jersey, for example Slipstream Sports or it could be the actual team sponsor itself, for example Euskaltel. But the rules say any team member can hold the licence. The “paying agent” is the person or entity in charge of running the team, the go-to contact.

The name

Teams are named after their sponsors. The naming rights are very valuable and often rare across sports. In cycling it is limited to no more than two names like Vacansoleil-DCM or Team Saxo-Tinkoff. Of course teams will have other sponsors and some like Garmin-Sharp try to drop in Barracuda or Radioshack-Nissan refers to itself as Radioshack-Nissan-Trek in its communications. Meanwhile many fans or outsiders will just say “Radioshack” and clearly the first name is the one that has paid for the privilege.

The Bank Guarantee

Before a pedal is turned a team must find at least 975,000 Swiss Francs (about US$1 million) which is held in reserve by a bank should the team collapse. This is to cover unpaid wages and other liabilities. It’s a big hurdle for new teams because it represents the single largest use of cash, way more than buying and fitting two luxury team coaches. But given the habit of vanishing teams it’s a useful barrier to sort out the teams with real money and those pretending.

Off You Go

With all the paperwork in place and a good roster of riders under contract everything is set for the team. There’s still more to do like taking out civil liability insurance for all riders and staff connected to their work. Plus a top team has to commit to development work with young riders. We see this with development teams like the Rabobank U-23 squad or the Itera-Katusha team that’s the kid partner to the Katusha team.

Oh and there’s the money. A team will have to meet several other costs during the year. There’s the minimum wage of €36,300 per rider or €29,370 for a neo-pro, there’s contributions to the anti-doping effort, there’s the cost of a licence and more in order to comply with the UCI rules.

Is it worth it?

Having explained the procedures and rules, is it worth it? This depends, there are a lot of expenses involved in obtaining the World Tour licence that don’t exist if you apply for a UCI Pro Continental licence, the tier below. UCI Pro Continental teams can still do the very biggest races but rely on invitations. If you are a French team then invitations to the Tour de France are likely so long as you have some decent riders, bonjour Europcar and probably Cofidis. Non-French teams have to be very strong to ride the Tour de France but it’s impossible to imagine Team Saxo-Tinkoff, were it to be demoted to Pro Conti level, to be left out of the Tour.

The World Tour licence’s prime attraction is an automatic entry into the Tour de France but it also comes with invites for all the other big races. FDJ are an interesting case because they want the licence to ride other grand tours. The sponsors don’t have much to gain but the team is keen to test its young roster during a three week race whilst being careful to pick its best riders for le Tour. By contrast Europcar has a lighter roster and doesn’t want to spread itself across as many races and so it doesn’t want the licence.

Conclusion

A sackful of money and plenty of box-ticking will get your team into the World Tour although it’s hard to pick a precise sum, a factor that can frustrate potential sponsors. But it’s not all about money, Garmin-Sharp’s budget is the same as Ag2r-La Mondiale and one of these teams wins more and gets their brands noticed around the world better than the other.

The Sporting Value assessment is the hardest part because it is a moving target, a team can sign riders with points only to find rival squads have made new signings and the game starts again and in the worst case the team ends up pleading its case with the Licence Commission. Plus the count is secret, fans and even the riders are not supposed to know.

By contrast the other criteria are predictable and published. There’s plenty of paper to print, accounts to prepare and bank guarantees to draft. Even the ethical aspect can be passed with planning. Indeed with a few accountants, lawyers, admin staff and a supportive sponsor all the above points are easy compared to running a pro team on the road for a year.

Thanks for explaining this. You know the teams when you see them but don’t get to see the work that goes into making the team.

There’s plenty more work to creating a team, from hiring riders and staff. It’s a big job, you are effectively creating a business with 50 employees to launch on a set date.

You say “it’s hard to pick a precise sum” but what kind of money are we talking?

The bare minimum with luck would be €6 million (US$7.5m) a year but €8 million is still a risk. €10 million should bring some certainty.

Thanks for such an enlightening post.

On the ethical front, earlier this year, some RSNT riders accused the team of not paying them wages. Has this matter been straightened out? I hadn’t heard about it as of late.

I think it’s been sorted but Katusha, Movistar and Radioshack-Nissan have been called to a UCI hearing, any remaining problems will have to cleared up here.

logically Saxo should suffer the chop but looks like FDJ will go down 🙁 I love French teams

Some things never change. All kinds of regulations and “box ticking” as you say while teams who appear corrupt as hell still get into the top tier while others may be excluded on the flimsiest of pretext. As much as I oppose any new scheme where ASO ends up with even more control of cycling than they have now, I’m starting to lean towards the idea that the entire UCI structure needs to be blown up and rebuilt in a clean and transparent way. The devil is of course in how this is done. Who would want to take this on without big financial rewards? The very kind of rewards that are in so many ways responsible for the current mess.

Europcar’s desire to avoid the obligations of riding 3 grand tours is an interesting case. I’ve said before that Euskaltel ought to consider following their example. Teams in France, Italy, and Spain with smaller budgets but a few very good riders are virtually guaranteed participation in their home grand tour. The problem is that not all the grand tours have equal prestige in the eyes of the public, so the Tour is the one thing everyone really wants entry into. The problem with the current WorldTour system is that some of the smaller teams fighting for a guaranteed ticket to the Tour aren’t as well suited to the other obligations that come it. It seems like we need a smaller group (12-15) of teams that get guaranteed entry into 3 grand tours, and a second level of teams that are guaranteed entry into at least one grand tour each season. To really make this work, of course, it would help to improve the prestige of the Giro and Vuelta.

Good observation. It is much like the promotion/relegation in futbol … I will use England as an example. All Championship teams strive to finish in the top 4 to battle for hopes to be promoted to the Premiership. The problem is that promotion to the EPL often destroys very good Championship teams. They have to increase budgets, buy more expensive players, take on significant liabilities in the hopes of staying in the top flight. When they get relegated, as most do within two years, they are left with huge financial burdens and no way to pay for them. Most of their good players have opt out contracts and so they must scramble for players and there is a huge tendency for them to fall another level within two years.

In these cases, financially they are much better off never getting to the top level but that doesn’t fit the model. I think the World Tour system has similar faults. Even a smaller number (say 10-12) should be gifted automatic admission to all 3 tours. Then let another 5 get 2 tour admission and perhaps another group getting 1. The reality is that the heavy hitters are few and so only 5-6 teams truly contend in all 3 tours. After the dust settled in implementing this I think we would see a general increase in “fun” in the Giro and Vuelta and a lot better race experience in the TdF.

I’ve had one further thought about this: the team roster should scale with the obligations. A small budget team that is limited in the number of riders it can sign can afford to spend more per rider. This could make the small teams attractive to up and coming riders who could still get a competitive paycheck and possibly a better chance riding a grand tour on a small team than fighting for a grand tour spot on one of the big budget teams.

Dead right! The number of teams let into the big league is just too many. There were plenty of arguments about this when the greedy boyz at UCI first announced this scheme, but of course they’re just interested in the license fees, so the more the merrier for them. A dozen rather than 18 would a) allow for the race organizers to invite more “wild-card” squads and b) make the entire peloton smaller if they invited 6 wild-cards. 18 teams total with 9 riders = 162, making things safer for everyone. Does anyone really notice a field of 200+ vs a smaller one? Back in the “golden age of cycling” 200+ rider fields were less common I think.

If these teams have financial accounts are these available? There would be no need to guess the budgets any more.

They exist and are sent to the UCI but I don’t think they’re public except for Team Sky. I’ve covered their accounts here and you can see the document online too http://inrng.com/2012/08/team-sky-budget-accounts/

Other teams have accounts lodged with various authorities but you might need access to the various national or federal registers.

Can somebody explain Spidertech’s strategy of suspending operations for a year — with its riders hopping onto other teams — so that Spidertech can focus on obtaining ProTour status?

I don’t think Spidertech’s “strategy” is overly complex. They found themselves short of money for 2013 and could not afford to honor contracts and run a race team. The whole “working for 2014” is just optimism on Steve Bauer’s and Josee Larocque’s part. These two form the parent company Cycle Sport Management (CSM). My take on the team running short of money is that some of the other sponsors, in the C10 grouping, like RIM (Blackberry) and Planet Energy (alternative natural gas business) are suffering through tough economic times and could or would not commit to the team for 2013. I still do not understand or buy into the logic that suspending the racing program in 2013 will lead to finding sponsorship to go to the World Tour in 2014. Seems like it is easier to sell an existing product to a potential sponsor than try to sell an essentially failed product.

Interesting to note that Tim Duggan was picked up by Saxo-Tinkoff and that Spidertech is coming on board as a sponsor of the team. I am pretty confidetn the salaries of all the riders are being paid by CSM for 2013 so the riders are getting spots on teams but the teams are not incurring any extra budget by signing ex-Spidertech riders. As to whether there is any retention of these riders if by some miracle CSM finds its money for 2014, I have not been able to determine this. I think every rider that has signed to another team so far is only on a one year deal so if Spidertech is resurrected they might all come back. But young riders with promising futures like Guillaume Boivin, Hugo Houle and David Boily may be courted by other teams.

Thank you for the explanation. the question that comes to my mind is does cycling now need something like a football league setup to allow teams that do not have millions to support them to compete and grow?