Pierre Tosi died on 1 April, aged 69. A modest rider, his very lack of achievement as a professional cyclist was the inspiration for the film Le Vélo de Ghislain Lambert.

Back in the days when Paris-Tours was a prestigious classic it was the one race that Eddy Merckx couldn’t win. “The Cannibal” had won everything else worth winning, and often many times over. Paris-Tours eluded him and 1972 winner Noël Vantyghem would joke that “Eddy Merckx and I won all the classics, I won Paris-Tours and he won the rest”. The joke’s on Vantyghem for his comparative lack of success but what of all the riders who end a pro career without a single win and who rarely tread a podium? There are many. Pierre Tosi was one and when asked what best career memory was by the Vélomane Vintage blog he replied:

When I beat Merckx for an intermediate sprint in Orléans, on the first stage of Paris-Nice, in 1974. He stayed on my back wheel

As L’Equipe wrote over the weekend he never started the Tour de France but did ride Paris-Roubaix once and started the Vuelta a España, only to abandon after three stages after getting a skin rash. He did get a podium finish, for example he took second place in the season-ending Putte-Kapellen, the race that straddles the Belgo-Dutch border with a finishing straight that is shared by the two countries. But there’s an irony to the result, Tosi got the result after coming back from a big crash, and the moment he hits form the season is over.

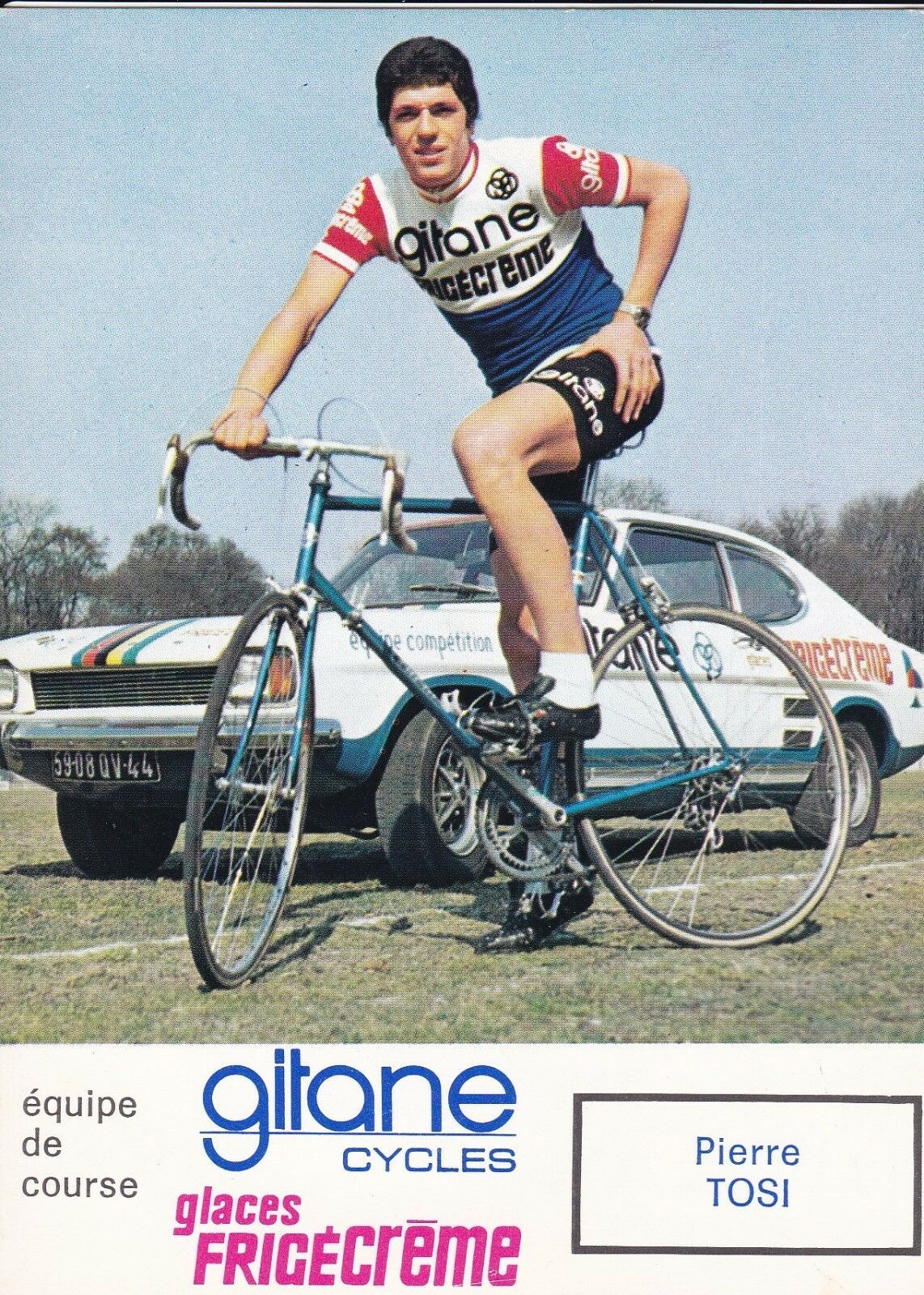

It’s this tragi-comic aspect that makes Tosi notable. Many ex-pros start new careers after hanging up their bike, or even burying their machine as Pierre Brambilla did in 1947 after losing the Tour de France. Tosi became a builder. But he also made a cultural contribution because he became the inspiration for the cult film Le Vélo de Ghislain Lambert by Philippe Harel. The plot synopsis is the story of a loser, “born on the same day as Eddy Merckx, but eight minutes later“, a hopeless rider at the mercy of selfish team mates, hapless team managers and fickle sponsors, who nevertheless finds fame because of his losses, an everyman who the public relate too rather than a ruthless cannibal. The public watching Le Vélo de Ghislain Lambert will laugh at the slapstick of a wobbling cyclist flying head first over the handlebars into a ditch; those with more interest in professional cycling will laugh at the knowing scenes of riders taking the best bed in a hotel on the eve of a race, the hypocrisy of a team manager or other inside jokes about pro cycling – including a bike being buried – so it’s a cheap comedy on the outside but loaded with cynical in-jokes. The film is deliberate about Tosi’s inspiration, the credits explicitly mention him and there are other references, Lambert’s Magicrème team is the synthesis of the Gitane-Frigécrème team for which Tosi rode in 1973 and Magiglace-Juaneda in 1974. The film draws on many anecdotes from the sport and Tosi gave plenty of them to Harel.

If the film is a comedy, Tosi’s cycling career wasn’t such a laugh. It’s not his tragedy, it’s a collective one where he and most of his peers found it a constant struggle just to get a contract and professional cycling was often amateurish in reality. While we look at the 1970s as a mythical era for cycling with the riders, the personalities, the lapels, sideburns and more – look at the team car behind Tosi in the picture above – the reality was not always as glorious. In the mid-1970s the going rate for a pro cyclist was 500-1,000 francs a month in France when the national minimum wage was 1,000 francs, and as Tosi joked in 2013 to the Vélomane Vintage blog that he was still waiting to be reimbursed for his travel expenses. He went bought his own Italian frame and have it resprayed as the team-issue bikes was too flexible. Tosi had a hard career and when this summer’s Tour de France celebrates Eddy Merckx’s illustrious career, take a moment to remember that if Merckx won almost everything, he didn’t win the intermediate sprint in Orléans in the 1974 Paris-Nice. Pierre Tosi did.

“Tosi had a hard career and when this summer’s Tour de France celebrates Eddy Merckx’s illustrious career, take a moment to remember that if Merckx won almost everything, he didn’t win the intermediate sprint in Orléans in the 1974 Paris-Nice. Pierre Tosi did.”

Lovely writing. Thank you.

Beautiful writing.

I’d never even heard of Pierre Tosi until the start of this article, but this closing paragraph almost brought me to tears!

Great post.

Bettiol’s recent (first) win got me wondering how many cyclists on pro-level teams never have a single career win. I bet it’s the rule and not the exception.

The stats aren’t obvious to find but in the World Tour peloton currently 23% of the riders have yet to win, but this isn’t the same as saying “a quarter never win once during a career” as among the 23% of winless riders there are many neo-pros who have time on their side. So maybe the figure is 5-15%?

There’s an excellent lecture on Youtube by Dr Louis Passfield touching on this and other topics – Find ‘Science of Cycling-How to be an Elite Cyclist’ by The Physiological Society.

In it I think he shows that 78% of riders never get so much as a top 10 placing in their entire career.

This is an interesting question.

Of course those that win tend to have longer careers, so you have to be clear what question you are asking. Measuring the “career winless share” of the population of pro cyclists at any one date will give you a different (smaller) answer than measuring the winless share among all those who have ever been pro cyclists at all over a longer period.

Bit confused by the apparent contradiction here. Is it 23% that have won, or 23% that haven’t?

Edited my comment above to make it clearer, it’s currently 23% of riders without a win. Interestingly the team with the most winners is Dimension Data, only two of their riders have yet win something and Sunweb is the other end of the scale, with 10 out of 26 still waiting for a win (38.5%)

Thanks for the stats. So more riders have wins than I had expected.

And yes – my original question was about how many finish their career without a win.

That’s for World Tour though – it might be higher among the Conti and Pro-Conti ranks.

He didn’t achieve much, but he achieved way, way more than me. RIP.

I wonder how many of us would love for a time machine to be invented and be able to go back and *watch*, never mind live, the sporting exploits of the past? This guy lived and did it.

I am not familiar with Tosi but I love the image above – cool bike, the haircut, the gear, Ford Capri MkI. Fantastic.

Well done sir, Chapeau.

Lovely.

He might not have achieved much, but I pretty much guarantee that if you met him on a training ride, he would show you a clean pair of heels. Just to participate at that level is enough.

Very true, he lead a stag race for amateur riders for several days, to turn pro is usually to be one of the most promising riders going.

“…the reality was not always as glorious. In the mid-1970s the going rate for a pro cyclist was 500-1,000 francs a month in France when the national minimum wage was 1,000 francs.”

I guess we’re very different in this respect. Part of he glory of that “mythical era” for me has a lot to do with guys racing not for the money, but for the passion and love of the sport. While there might be as much passion and love today, it’s harder to see in the sport now, when the riders no longer have to do much more than pedal the bikes and wipe their own a–, with someone else handling everything else.

If you want to see people racing for passion and not money, then check out Women’s Pro Cycling…!

+1

Definately not for the money…

https://twitter.com/Laura_Scott/status/1115709682927263757

Good point! Who knows? Could this era end up being looked back upon as the Golden Age for women’s cycling? Maybe, but for me those days are more like the 80’s when American women like Rebecca Twigg and Connie Carpenter competed against Maria Canins. They were certainly not in it for the money!

PS-my wife raced as what was then called a “pro” during this era so I admit to being biased here. I have a podium photo of her on the second step below Twigg and above Connie Paraskevin-Young from this era. Believe me – she wasn’t in it for the money!!!

Rebecca Twigg is a blast from the past, blood doper iirc

Huge plus 1

Larry – are you glory days rooted in the 80’s?!?

There was that guy in the 80’s who demanded a big pay cheque and ensured riders henceforth got more financial rewards for their efforts rather than being exploited by nasty tight fisted team managers. Lemond I think he was called. Can’t think where he was from though…

Interesting point, but remember Greg LeMond was signed as a pro first by the tight-fisted Guimard with Hinault’s help. Only when Bernard Tapie (perhaps the prototype for Oleg Tinkov?) showed up with his fat checkbook did things really change. I doubt LeMond would have called it quits on his cycling career had Tapie not come round. We’ll never know, though LeMond himself has claimed plenty of Tapie’s promised money never showed up.

Once LeMond started having some success, the multinational sponsors started to sniff around for bargain-priced promotional opportunities and as they say, the rest is history. In hindsight I’m not so sure their contributions to the sport were entirely positive.

Lovely piece. Thank you.

Good you linked to your archive too (being a regular on here I’d missed that entry). Film’s on order.

I saw the film at my local arts cinema here in France. Just the memory makes of it me smile anew, while IR’s writing captures so much of that time. Great days: Verbeeck, De Vlaeminck, Maertens, Knetemann, Danguillaume, Pollentier, Gimondi…and Hoban. IR always finds a new angle on our sport. Thanks.

Nice piece, not many people on this earth can say they beat Merckx in a sprint.

Great story! Chapeau.

How tall was he? That head tube is big.

They often had bigger frames then but he himself was a big frame, 1m88 apparently.

Wonderful read.

You have a talent for bringing vivid colour to the lives of people spent in the shadows of cycling royalty.