Many athletic sports have their references, benchmarks and records. Running a mile under four minutes, breaking 10 seconds for the 100m sprint, sailing around the world in under 80 days and maybe one day doing a marathon under two hours. But road cycling has none of these, we barely notice the time taken to complete a race and usually the average speed is immaterial. Absolute speed counts for little. Everything is relative.

Sometimes it can be hard to review. When a rider wins a race were they the strongest on the day, are they the fastest in history? When Fabian Cancellara took Simon Gerrans to the finish in Milan-Sanremo who was the better rider? This caused debate at the time but history records only one name. But what if we could take more measurements during a race. Are there new measures we can use to compare performances or do these not matter?

We can compare times in specific examples in the sport. Probably the best example of this is the ascent of Alpe d’Huez where each time the Tour de France climbs up the times are noted. The last time it happened the day’s official results included the climbing times, something that doesn’t happen elsewhere. There’s reference for other climbs even if they’ve appeared in the race more often like the Col du Tourmalet. There is a record for Mont Ventoux which means times next year could be compared but Ventoux is famously windy meaning comparisons are hard.

There are other timings to capture. We measure the time taken for the final 200 metres of a sprint stage in a grand tour to measure the speed of the sprint, something a human with a stopwatch could do. But today technology offers the chance for much more. The timing chips used could allow perfect timing and better still, tracking technology should be able to monitor riders in the final kilometre to time them and even give us the rider with the highest top speed. It need not just be for a sprint finish, anything can be timed such as the time taken to complete a cobbled sector in Paris-Roubaix. Personally I’d be fascinated to see the split times for each portion of pavé to see if the data show anything but it would probably bore many.

But does all this matter? Perhaps one rider might hit the highest speed of the day and, say, reach 75km/h in the sprint but if they finish third then it doesn’t matter, everyone wants to know who won. The same for climbing times which might be of interest to keen fans but the wider public finds it hard to make the comparisons, they are not well-known references. Nor are they comparable because the wind is so determinant on Mont Ventoux that it defines how riders tackle the final climb. Indeed tactical considerations always come to the fore, if Alpe d’Huez is rarely windy then the main factor is the race itself, riders rarely pace themselves uphill but judge their effort against others: it is not the time taken to climb the Alpe that matters but what happens on the slopes.

Plus these benchmarks might be ones to forget. EPO and blood doping have polluted the results meaning times taken from recent years are as meaningless as a Lance Armstrong victory, that’s why his Tour titles were not reallocated because so many other riders were doping meaning the results became pharmaceutically falsified by the likes of Michele Ferrari, Eufemiano Fuentes and others.

But Ferrari’s contribution is not all sinister. He has created the measure of VAM or la velocità ascensionale media meaning the average climbing speed. It expresses the vertical gain over time, for example take the Bola del Mundo climb in Vuelta. We know the difference in elevation between the start of the climb and the finish and so armed with timer we can clock the riders. Climbing is always good for comparisons because riders benefit less from drafting each other as the speeds are slow, therefore it is much more about individual performances. But VAM is imperfect as the steeper the slope, the higher the score. Taken to the extreme, you can score a giant VAM number when sprinting across a canal bridge in Belgium but a low number when tackling the Passo Pordoi in the Dolomites. In other words the number is not comparable and even amongst Alpine climbs because changes in slope matters. Here’s Wikipedia:

For example, a 1650 VAM on a climb of 8 percent average grade is a performance equivalent to a VAM of 1700 on 9 percent average grade. Ambient conditions (e.g. friction, air resistance) have less effect on steeper slopes (absorb less power) since speeds are lower than on gentler slopes.

As we see it starts to get technical, it is suitable for coaching and technical analysis but not the kind of rankings the public can adopt because it varies, it’s technical.

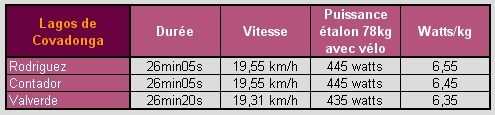

The most comparable and viable analysis is the use of watts adjusted for rider weight. The measurement of W/kg is the gold standard when it comes to comparing climbing performances in a race. But the numbers are rarely made public, leaving some to make estimations.

And again I don’t think the public will take to this either. Readers of this blog and those with an interest in sports science might want to see the numbers but they’re hard to understand. Again the numbers vary according to the climb. In an excellent interview FDJ coach Fred Grappe explains the numbers (my translation):

“In between a climb like Verbier that lasts 20 minutes, and climbing the Tourmalet which is an hour, there’s a gap of 40 minutes. This time period weighs heavily on the power output. We know today (thanks to research conducted over several years in my lab in Besançon) that a rider loses on average one watt for every extra minute between 20 to 60 minutes at their threshold. In other words it means that all athletes will lose between 40-50W going from a climb like Verbier to the Tourmalet.“

Verbier’s a Swiss ski resort and the climb is relatively short 8.7km, compared to about 20km for the mighty Tourmalet. There are other factors too and even if the atmospheric conditions are identical (wind and air pressure alike) then the road surface is a factor too. Again I’m having to explain this measure and we have to check the factors on the day so W/kg still doesn’t quite work, at least not for the wider public if they want to compare riders.

We need to be careful with data. As we’ve seen over recent years there’s been a tendency to latch onto particular numbers. If the climbing times are low then this is “proof” that doping has gone away. If a rider gets a high VAM then this is “proof” of doping. Even the average speed of the Tour de France has been used to make the same claims. But in reality the numbers can only support a hypothesis, they are not proof.

It seems references over the years are too hard. Even in athletics where stadiums and tracks are designed to specific rules a result only counts for a world record if the wind speed is suitable so looking for comparable times on the open roads, whether the plains of northern France or the passes of the Pyrenees, looks impossible. Perhaps the only comparison is the overall number of wins. Cycling is rich in history, not data. When Tom Boonen won Paris-Roubaix this year nobody timed his speed through the Arenberg nor his final lap of the velodrome. Instead the comparison to Roger De Vlaeminck arose because only Boonen and De Vlaeminck have won four times in Roubaix. Similarly some roads take on notoriety because history to the point where we know we cannot compare climbing the Galibier today with the first ascension of the Tour de France in 1911 because the roads have been surfaced, the bikes have changed and so has the distance of the stages. But this did not stop the Tour de France building a narrative around this in 2011.

Indeed often the best races are the slowest, the ones where riders have emptied the tank too early, where they crack live on TV as their rivals ride on up the road. In other words, it’s about forcing your rivals to use up their energy before you use yours. Some famous words from Tim Krabbé’s The Rider:

“Racing is licking your opponent’s plate clean before starting on your own.”

– Hennie Kuiper

Or take the drama of a sprint finish where a breakaway approaches the finish and starts to play around, even slowing to a crawl before sprinting to the line for a photofinish. The only pacemaker here is the one inside the chest of some viewers as the suspense of a race rises and spectator heart rates soar. It’s not about the absolute speed but the relative efforts.

Conclusion

It would be good if we could compare performances over the years but there are so many variables on the open road that making comparisons is fraught with problems. We cannot compare simple times and other attempts soon end up mired in spreadsheets, phrases like “margin for error” and “adjusting for” appear.

So whilst cycling is a sport about athleticism and human performance, often absolute measures of output are only anecdotal when telling the story of a race, races are relative. We might be curious to know the watts or even how many calories a rider burned during a stage but the public want to know who wins and the only timing that matters is usually the margin of victory. Indeed even in a time trial the average speed is a curiosity but it is still the time gaps relative to others that tell the story of the race.

I’m sympathetic to providing information for what we could kindly call “sports geeks” so that the information is there for analysis but often victory in a race is about tactics rather than performance and the only absolute measures are those in history where riders of today are compared to those of the past via the number of wins.

Great piece

Not as good as some of the others, though.

I’ll get my coat…

That is why all “extraordinary” TT specialist should try to break the hour record, – Conte la montre 🙂

I’m all for bringing back the hour – Wiggins with his sense of history (at least in wanting to win the Giro rather than another tour) would be the ideal candidate.

Also, I recall another quote from “The Rider” suitable for this discussion:

“Every once in a while someone along the road lets us know how far behind we are. A man shouts: ‘Faster!’ He probably thinks bicycle racing is about going fast.”

+1. I immediately thought of that quote from Tim Krabbe’s book.

While I might be a data nerd about my own riding I have no interest in it for pro road racing because, ultimately, it’s not really what counts. And there’s so many other aspects of road racing that are interesting that this one just doesn’t do it for me.

TT times on the track, however…

+1

I would love to see more attempts.

It would be great to see that, but sadly the UCI in their infinite wisdom decided to kill it with ridiculously backward rules (DR Hutch’s “the hour” is a great insight into this) Might get some takers if they just reverted to using the legal 4000m IP rules of the day.

‘but often victory in a race is about tactics rather than performance’

Not in SKY country.

Wrong.

“We know today (thanks to research conducted over several years in my lab in Besançon) that a rider loses on average one watt for every extra minute between 20 to 60 minutes at their threshold. In other words it means that all athletes will lose between 40-50W going from a climb like Verbier to the Tourmalet.“

Really? I thought it was more like 5% power lost between 20 min and 60 min. 40-50w is more like 10% for a pro rider — bad translation or does Grappe’s research reveal something that Coggan’s stuff doesn’t?

Wiggins’s numbers circa 2009 (476W and 482W in two 10 mile TTs, and 434W in final tour TT (49 mins)) match up to this.

(ref: http://forum.cyclingnews.com/showpost.php?p=73896&postcount=53)

The ‘Coggan’ 20 minute test is supposed to be performed after an all out 5 minute effort to use up your VO2/AWC system – it’s not a best effort over 20 minutes. Something like that anyway.

That is not Coggan’s test. It’s one proposed by coach and author Hunter Allen.

Coggan has never said hour power and 20-min power differ by 5%.

The relationship between 20-min and 60-min power is typically within a range with mean maximal hour power ~ 90% – 95% of 20-min mean maximal power. Sometimes a bit less, sometimes a bit more.

Keep in mind what athletes actually do on a climb is not always what they could potentially have done on a climb. In a race there are many other factors as this post mentions.

Nevertheless, I think some of the viewing public *are* interested in the physical and physiological factors that go into a win, so what’s wrong with providing the information if it’s available, accurate and relevant? We see such things in many other sports as technology improves, and besides, a little better education on such things might give commentators something better to talk about.

The problem I see is speculation on performance factors inferred from incomplete data (such as VAM) being conveyed as accurate or factual.

I guess you also read the pieces on http://www.fietsica.be or http://www.bloggen.be/fietsica

It’s a great site with information about physics (fysica in Dutch) in cycling provided by prof. Charles Dauwe. He also suggests something named as the ‘power-watchdog’: all riders should donate their race info from their powermeters into a databank where they can look for VAM’s that are too high, but as with many things in cycling world, it’ll be difficult to reach an agreement between different parties.

Maybe the big audience isn’t that interested in the numbers but it’s a good thing to talk about it.

Commentators on tv have so many time in races so it’s a good topic to chat about, although passive cycling enthousiasts won’t get a thing of it (as it also the case when they’re talkings about cycling gears).

As a member on Strava it’s a nice way to compare climbing times with others, another site http://www.veloviewer.com is a nice addition and provides more info about VAM and W/kg, the numbers depend on so many things but I like it as an estimation of power ratings..

No point trying to gather pro power meter data as a means to identify possible doping. We’ll just end up with “data doping” to add to the mess we already have.

I’ve previously written on this issue of comparing climbing times and estimating W/kg in this item (and the uncertainty of this approach which is one of the points inrng makes):

http://alex-cycle.blogspot.com.au/2010/07/ascent-rates-and-power-to-body-mass.html

road cycling isn’t unique in not having simple records and stats- in sailing, Speed Sailing is a separate branch of the sport (and for the short distance stuff involves weird craft that would be useless as race boats- a bit like outright human powered record machines like Obree’s Beastie).

Yeah but sailing is not a real sport, it would be like if in cycling you had an olympic medal for each of the following categories- bikes with 36 spoked wheels, 24 spoked wheels, trainer wheels, bikes with fluffy seats , I have already run out of classes (need 11 medals to match Olympic Sailing) but the imagination of the sailing fraternity knows no bounds to ensure no one goes home without a trophy :). If the piece is about relative performance v objective data – the highest levels of athletic performance in sailing is relative to the junior club cycling championship in Eastern Tajikistan and that’s objective!

There were 18 medal events for cycling in the 2012 Olympics. There were ten (not 11) for sailing.

When the sailors propel the boat, then I’ll agree that it’s a sport.

A few thoughts come to mind reading these few comments:

– if sailing is not a sport because wind propels the boats, then neither is downhill skiing, bobsled or diving, since gravity does the work

– It’s called the Olympic *Games*

– as for classes within a sport, one could easily extend that argument to swimming, weightlifting, walking v running, boxing, judo, wrestling, taikwondo, rowing, not to mention separating male and female categories and basically just end up in a logical conundrum.

– fitness is pretty important in sailing, not the most important consideration of course, but that per se is not sufficient rationale for it not to be considered a sport. e.g. how fit are some baseballers or cricketers? Is Golf a sport? I imagine Palmer, Nicklaus, Faldo, Woods, Norman et al would say it is – yet here are some of the world’s best golfers:

http://i220.photobucket.com/albums/dd226/ASimmons/FatProGolfers-1.jpg

Good article. Jean-Paul Vespini has a good discussion in ‘The Tour is Won on the Alpe’ about different climbing distances used on Alpe d’Huez, which makes comparisons difficult.

Or does it? On the Col d’Eze table, for example, the climb distances vary but the average speed provides an interesting comparison. Correlation is not causation, as folks like to say, but the average speed in the 1990s is the highest (as it is for most other climbs) – and we know why. So perhaps this just confirms what we already know.

But what about Jeff Bernard in 1992? His average speed might raise a red flag, but we’ve no way of being sure based just on the numbers. Was it just a good day for climbing? The numbers can be indicative of something, which is just stating the obvious, so I’d have to agree with the approach above that there are too many ‘variables’ to be sure. Still, crunching the numbers can be fun!

As usual, a great article…

For me, a medium-data nerd, the Pro numbers are only of interest to reflect on them relative – theres that work again – to my own. Clearly, my VAM going up some crappy Strava hill means nothing compared to a Pro like wiggins maintaining 1800 for an hour whilst going up and baggins a col.

Point of interest – i crunched a load of numbers on male/female marathoners since records began (1896 olympic games) and the 2h marathon will not be broken, i predict with almost 99% certainty!

I assume you mean a “clean” 2 h marathon…

Nicely written, but I would NOT like to see more number crunching and performance data. The race is won by the racer who crosses the line FIRST and that’s the way it should be. The hour record is just fine for those who want absolutes, minimizing the effects of machine and environment but PLEASE leave it at that. I’ve said before that if we start handing out the yellow jersey based on VAM and watts and VO2 max we may as well just put the competitors on stationary trainers set up along the Champs in Paris and skip all the expense and bother of three weeks of racing around France. It’s a bicycle RACE after all!

I absolutely agree wit Larry T.

Cycling has so much more to offer than riding fast on a bike (Although a lot is exactly about that). It’s also about the (team) tactics and the fight mano-a-mano. These battles, sometimes duels are what shape the race and are it’s beauty, and it is totally irrelevant how fast the riders rode up some climb or some stage or race.

That is also a reason, although rooted very deeply in this sport, it doesn’t need any doping for spectacle, (There are other reasons which are no excuse but to some point make it understandable why somebody took this bad decision) unlike other sports for example athletics. There too one can have a spectacle without doping but the higher faster wider credo leads to premium money only through new (world) records. And you know what, I totally believe it is possible to run the 100m dash in under 10 s (for some), but how constantly the top sprinters run beneath that border and the number of them, that I fear is due to pharmaceutical aid.

So a big NO to (nonsense) stats. I know especially Americans are very fond of stats, but if you love stats, than you should maybe refer to a different sport than cycling, your “American” sports like basketball, baseball or what they call football in the US is much better suited for stats lovers.

Also, if these GPS trackers on the bikes would be preciser it would be much more interesting to follow the lines and the positions of the riders during a sprint finale instead of clocking intermediate times. That would be something much interesting and educating. And even the casual spectator could discuss more about it than about some estranged figures. (like “Oh, he should have shut the door on the left so Cav would not have passed him, Roelands on his right was no threat.” or “He was too far on the outside of that bend, he should have moved earlier to the front in this finale.”) What if…scenarios are very popular discussion topics in any sports (but also a lot of other topics like physics and history and and and).

Cycling records are done on the track

1hr

4k pursuit

1km TT

200m flying

etc

I think some stats are really interesting and just enhance the viewing experience on TV so long as people don’t get too worked up about it as being anything other than that.

The Vuelta was good at having “live” gradients on the climbs & current speeds. The Tour of Switzerland a few years back had Cancellara hooked up to a powermeter which could be seen live on TV – I was fascinated to watch the power “crank up” when he was riding back from the cars. Heart rates would similarly be good. Let’sd have some GoPro cameras in the peloton too.

Record times for climbs are interesting in a way but, as mentioned above, the doping era has spoilt that as being anything particularly meaningful (other than perhaps serve as a “canary in the mine” should the sport return to its dark days).

…and that’ s why road cycling is such a beautiful sport! You can’t quantify everything in it and can’t predict success only based on numbers. Look what the records do to track cycling…anyone watched it outside the Olympics? Cycling is all about emotion and passion….the sprinters positioning, the attackers courage, the climbers suffering…Boonen doing an “unnecessary” 50km solo in Roubaix out of pure passion or a Contador going all-or-nothing kamikaze in La Vuelta. Gotta love this sport!

Very good piece, one of the best on this blog. “Often the best races are the slowest”: quite true.

Reminded me of one of Vockler’s stage wins in the tour this year, when he and 3 others I think crawled to the line having given everything. The suspense and drama was as great as for a bunch sprint.

Personally, I love it when we occasionally get power meter stats from the pros, after the race.

But I’m not sure I really want to know during live broadcasts.

Great article.

As a mortal, I live and die by my power meter. Knowing how much more I need to produce to become PRO fast is my life’s credo. This is why numbers are important to me – and probably a lot of other amateur athletes.

For a pro, what do the numbers really tell you? They are so finely in tune with their bodies, they know what 380, 385, and 400 watts feels like – so power meters are slightly redundant. Also, I doubt any of them are looking at their current output – they have a lot of other things to think about while racing. An analogy – do you really think Schumacher or Vettel have time to look at their speeds while racing @ 300kph? The speed is for the pit boss/engineer to determine if modifications are required on the next pit. The power files are for the team coach/physiologist to identify gaps or increases in particular measures…

And yes, the spectacle of racing is visual. Empty tanks, counter-attacks, and gambles. No power file ever tells that story. The story is what is exciting and gripping.

Thanks for the post…

Yes for sure, I rarely even glance at metrics during a race, but at pro level with telemetrics going back to the DSs vehicle it’s a different ball game. As a spectator I prefer to be informed of the tactical nuances of any given situation.

Cycling – unquantifiable, unpredictable, wonderful.

BUT I have enjoyed the addition of gradient info in recent times and I’d love to have some way of knowing exactly where individual riders are, outside of those covered by the camera bikes. I’m especially thinking of mountain stages where it’s difficult to know if a GC hopeful has just exploded or the sprinters are struggling for the time limit etc.

Nice article again. But not very specific to cycling I think. There are only a few sports where you can keep track of world records. Athletics, track cycling, swimming, speedskating come to mind, I’m surely forgetting a few. Most other sports we can only compare over the years by what people or teams have won in their day. Nobody cares about the world record for number of goals in one match a team scored in football/soccer. The stats for serve speed are kept in tennis but they are only a sideshow, etc etc.

Another good review on the use of measured output.

I would rather rely on my own observations of a rider, both on the bike and, off to draw my own conclusions about performance. This method has served me well over the years