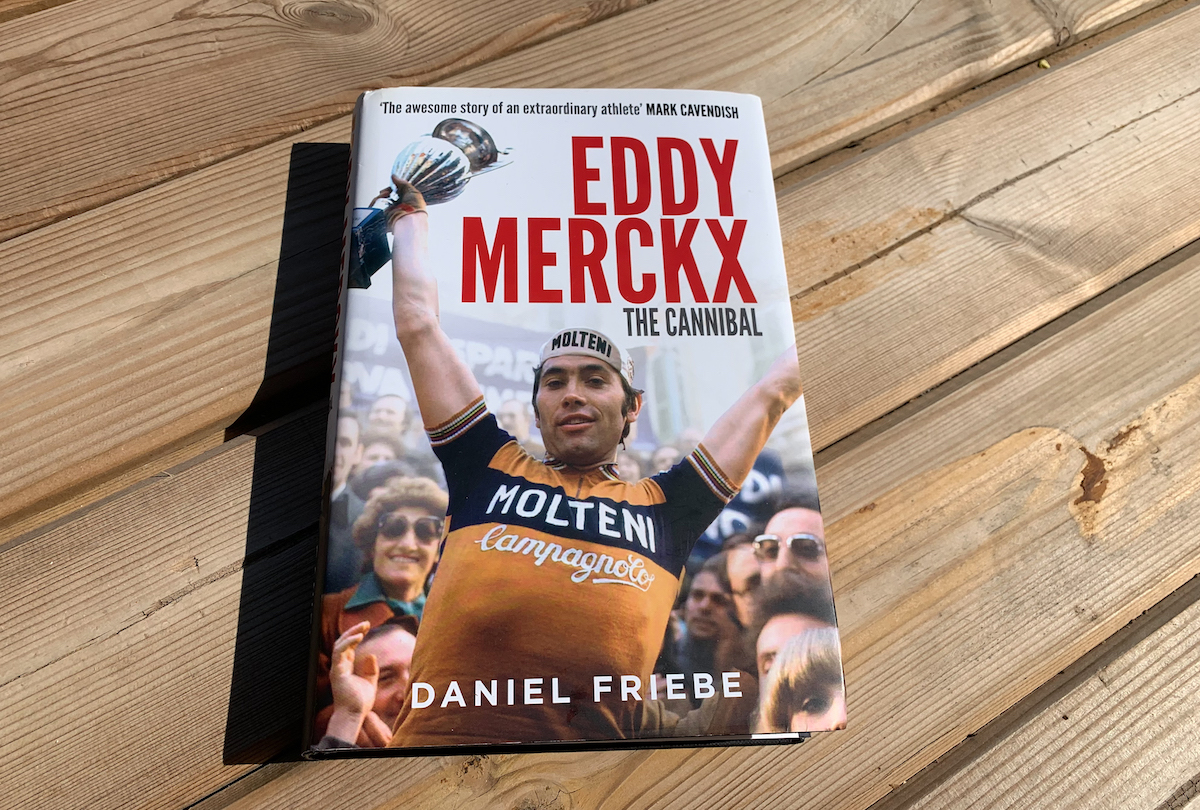

Eddy Merckx, The Cannibal by Daniel Friebe

Having reviewed “Eddy Merckx The Cannibal” soon after publication a decade ago, it’s been back on this summer’s reading list in the light of Tadej Pogačar’s results and frequent comparisons to Eddy Merckx. Plus it’s Merckx’s birthday today, 79 years old..

With Tadej Pogačar racking up wins and often by a comfortable margin there are inevitable comparisons with Eddy Merckx, the reference point in the sport. These are often quantitative comparisons, such as the first rider to do this-or-that since Merckx, the biggest winning margin since Merckx, a plethora of what sports fans call statistics and what statisticians often call anecdotes.

What’s enjoyable with this book is that there’s so much on the qualitative side, it’s full of tales and not numbers. Yes Merckx wins often, he wins big and he really hates losing. Here it’s the stories and even the psychology that makes it an entertaining and informative read. As an example one of Merckx’s masterpieces was the the stage from Luchon to Mourenx in the 1969 Tour de France, he won it by almost eight minutes but Raymond Riotte put it better, “he was in the shower and we still had 15 kilometres to ride” which says more than the actual eight minute winning margin that day.

The author didn’t interview Merckx – a “blessing” writes the Friebe – but instead spoke many of his challengers and plenty who got crushed at the time, seeing their income drying up but are nowadays happy with their lot. Because of the many voices it’s a useful corrective. To reprise the Mourenx win again, Merckx often says he attacked because he heard his team mate Martin Van Den Bossche was leaving the squad and he didn’t like this act of disloyalty and, so in a fit of pique, chased down Van Den Bossche on the Tourmalet and then he kept going to the famous win:

“We’d learned the evening before that he was going to join the Molteni team, that was a hard thing to take, a disappointment because he could have waited for another moment…. …it was to deny him the points for the mountains competition that I attacked on the Tourmalet, before finding myself alone at the front”

– L’Equipe special edition “Impera-Tour”, June 2024

But Van Den Bossche is interviewed here and says Merckx did not know about the contract for the following year and was just being Merckx in trying to win everything going. Who is right? That’s not clear but Merckx is able to give his version events more often than the others, the winners get others to write their history.

The book touches on Merckx’s popularity. When the first lunar landings were happening Merckx was regularly sharing the front page with the Apollo module or Messrs Armstrong and Aldrin. “Fans” would leap over fences to get into his garden and steal his jerseys drying on the washing line.

Rivalries and challengers abound. Merckx won plenty but others were able to find opportunities. What’s interesting is how Merckx’s arrival on the scene and some of his wild moves at the start set the scene for years to come. Even Merckx later admits some of his long range attacks were reckless but with hindsight these cowed the others who saw him as near-unbeatable so they often didn’t try when it could have worked from time to time to challenge him directly.

Today the lack of rivalry is remarkable, to the point where it’s invisible. Framed against the tales in this book it’s arguably the big contrast between now and then. Yes Merckx is wearing a wool jersey and pulling chicken legs out of his musette as race food while today it’s lycra racesuits and gels. But it’s the personal clashes that stand out from the past era.

Pogačar may be the master of so much but Jonas Vingegaard has beaten him twice in the Tour de France. Yet there’s little rivalry between the two, just exchanges of polite words at the foot of the podium truck and talk of respect. Which is pleasant and good for them but it may not make for a sizzling read in decades to come. Similarly Wout van Aert and Mathieu van der Poel are arch rivals on the road and probably would not go on holiday together but it’s hardly Merckx vs. Rik van Looy or Roger Roger De Vlaeminck and the book puts it all in stark relief.

The Verdict

Enjoyable a second time over, although it pays to sit down and read one chapter at a time rather than do more in a sitting so as not to be overwhelmed by the list of triumphs. There are other books to enjoy, William Fotheringham’s biography the other choice in English; in French there’s Merckx’s own “Mes Carnets Routes” diary, or Philippe Brunel’s biography and more. They surely all suggest that Merckx’s domination was near-absolute, both in terms of results but also the mentality and the way he imposed himself on the sport.

The recent Giro did see Pogačar run off with the race and he’s been doing this in other races like Strade Bianche and the Volta a Catalunya; yet Merckx did throughout the season, for many years and often infuriating his rivals. Pogačar hopefully won’t have it so easy this July.

More books to read at inrng.com/books

Having observed both riders it is difficult to compare them given the passage of time. Merckx certainly rode long, tough seasons with numerous dominating Classics and Tour victories, aided by a strong devoted team.

Pogacar’s Giro performance was certainly impressive, with plenty of crowd pleasing panache. BUT the opposition was pretty weak. I think the jury is still out on the difficult question of comparing the two riders. Maybe the next few seasons will provide a definitive answer, or maybe not!

“Pogacar’s Giro performance was certainly impressive, with plenty of crowd pleasing panache. BUT the opposition was pretty weak.”

Agreed, but whose fault is that? LeMond gets (unfairly IMHO) blamed (by Merckx and others) for making LeTour the be-all/end-all of the cycling season but too many hide-out in high altitude training camps when they should be racing!

Makes no sense to me..all the superior modern training/nutrition/recovery/blah-blah means today’s racers can only race LESS, not more? And careers are shorter, not longer? Makes me shake my head at all the claims of innovation in the sport being branded as “progress”. WTF?

People tend to forget that LeMond was 4th in Roubaix and continued to ride the classics throughout his entire career. The Tour as “be all and end all” really began later with he-who-shall-not-be-named. Merckx should have known better, but it wasn’t the first (or last) time he’s said ridiculous things.

Merckx famously accused LeMond of making TdF the be-all/end-all in the pages of The Fabulous World of Cycling. The Cannibal didn’t seem to have the same disdain for that punk from Texas, perhaps due to some commercial ties?

Are careers really shorter these days? Merckx and Gimondi both rode 13/14 seasons (1965 – 1978). Hinault only rode 12 (1975 – 1986). Zoetemelk (who would generally be considered to have a long career, spanning the Merckx and Hinault eras) rode 18 (1970 – 1987). Poulidor likewise (1960 – 1977). Simpson, turned pro at the end of 1959 and, writing in his book, reckoned he’d have retired by 1970 (fate intervened, of course). By contrast Geraint Thomas and Mark Cavendish both rode the Tour de France in 2007 and are likely to be on the start line in 2024. Valverde rode 20 seasons. Domenico Pozzovivo has just ridden his 18th Giro.

Outliers (like Valverde) will always be outliers of course, but I think you’d have to do the analysis to see whether careers really were shorter or longer now. If anything, I suspect that riders last longer now, for a couple of reasons – one being fewer racing days and on average racing days being fewer hours, which leads to less wear and tear on the body. Secondly, there is more of a “safety net” of lower divisions (and better money) such that a rider dropping out of the top division these days has the possibility of a year or two are Conti level and can then return to teh top level. A rider who failed to get a contract at the end of a season in the 1970s probably had little option except to give up and find a different job. So my hunch is that there was more turnover of riders having very short (1 – 2 year) careers. We remember the Poulidor’s, Zoetemelks and Aghostinhos because they were outliners, but forget those who got a pro career, maybe scraped a 5th on a stage in some early season stage race and a 3rd in a Kermesse in July when no-one was watching and then slipped silently back into the local factory when their contract wasn’t renewed in February the following year …

“Are careers really shorter these days?”

It’s easy to find remarkable examples of current riders, or recently retired riders, who began professional racing 14-15 years ago, so the case can be made that many careers aren’t shorter now. But those examples don’t tell us anything about the average career lengths, especially of the standout riders (and here I don’t mean the monsters who end up on the ‘all-time greats’ list, but those who manage to win at least a handful of significant significant races and who animate many more races). Consider ‘survivor bias’ when looking at statistics. For example, many people ignored reports that smoking cigarettes led to dramatically higher risks of cancer, heart attacks, and shortened lifespans by pointing to the thousands of regular smokers who were still alive and outwardly healthy into their 70s and even 80s. But of course the average lifespan for a smoker was and is shorter, while health complications are much higher. If you focus on the survivors, you miss the real story.

I don’t think we know for sure if riders who blossom early have shorter careers or not, since the percentage of such riders in the past was very small. I looked at the career starts and ends for the top 30 all-time riders recently, and it does appear that riders who start winning significant races at very young ages (19 or 20) tend to peak earlier and stop winning at a younger age than those who start winning a few years later. For example, the extreme outlier Valverde didn’t start to show his quality until he was 23. Merckx was, on this score, exceptional in having a very early start to his dominance, and for making it last as long as he did. Zoetemelk started winning at 23, Thomas (on the road) at 24 (and, notably, he’s been a very good rider but never near being one of the greats), and so on.

Ten or twelve years from now we’ll be looking back at this amazing cohort of incredibly talented riders, who have started riding the biggest races and taking major wins at very early ages, and seeing who among them are still winning, or have already retired, or soon settled into super-domestique/rare winner roles.

I’ll also add that we do have a clear trend regarding the peaks for pro riders (peak defined as the year or years of their best results relative to the peloton). It’s gone from ages 28-29 decades ago steadily down to 25-26 years old. If the peaks are happening sooner, then the ‘tails’ of the career performance curves need to get longer for the average careers of winning riders to hold steady. That will be difficult as we seem to have a genuine trend of young riders entering the World Tour level. Team managers have a huge incentive to sign relatively cheaper young riders who have the additional benefit of huge potential upside, vs. holding onto relatively expensive veteran riders who are past their prime.

I’d change “started to show his quality” above with “seriously competing at top level” because Valverde started to show his quality before he even was a teenager ^___^

This is just a fun remark but underlines a more serious aspect. Teams often simply decided not to have promising athletes race at top level before they were 23 or so for a series of “cultural” reasons which I won’t delve into right now.

Valverde was an amateur until 21 included – and at 22, even if the team opted for a reduced calendar with soft preparation, he could have easily won a couple of now WT stages, namely at the Volta and the Vuelta, as he beat the best-men-group on the line (but there was a break ahead).

I’d also be very curious to know how you derived the data about riders hitting their prime at “28-29 decades ago”. 29, through the broader peloton, has always been an age of slight physical decline or last light before sunset, in terms of sheer results, with obvious exceptions. But it’s hard to measure that without a method. I proposed similar concepts to what you write above on these same pages, but when speaking of figures I used PCS which offers age datasets only as far back as the ridere active at the end of the 90s (at least for free, dunno if there’s much with any pay access). And you easily notice that in these last 2-3 decades 29 was never a peak of sort, barring perhaps the 2000s when it was part of 27-29 plateau of sort. Which, by the way, denies in a way that the process is steady, given that the previous generation had an earlier peak and decline (albeit with a slowly later growth).

Barring these details, I agree with a good part of what you write above. I think that it’s hard to make comparisons because we’re facing a cultural shift unprecedented in the modern version of the sport. I.e., having champions who start early their career is similar to other eras of cycling, but the rest of the sport (prep, metabolic interventions, “science”, etc.) is more akin to what we’ve been having from 2-3 decades and very different from what happened before. So we’re really into unknown terrain and, as you say, it’s very interesting to wait and look how things will develop.

Ah, I nearly forgot. If you used PCS to set the all-time top 30, I suspect it’s a big mistake because one bias that list has got is very related under some respects to the factors you want to analyse (it’s more quantitative than qualitative and so rewards long, steady careers with many victories or placings irrespective of quality peak levels). That said, maybe 30 are enough to compensate.

The 30s. Bartali hit the road winning at 20, before he only had raced at (then very) amateur level and his career stretched with big wins well into his late thirties.

The 50s. On a different scale, Poblet was winning big among the pros before he was 20 and still was well after he was 30… (’59 and ’60 being among his finest seasons).

The 70s. Baronchelli at 20 didn’t “win” a single race… but was 2nd at the Giro 12 *seconds* behind… Merckx. He won his last Lombardia at 33.

– – – – –

(Generally speaking, I believe that the main factor is probably the role played by pro-amateur ranks where you already could earn money as a strong athlete and which was considered the best growth path to take from junior until you were 22-23 yo for some 50 years. The wars also had a huge impact on the careers which developed through the 40s and well into the 50s, actually).

Valverde is still a pro rider though. Just on gravel. I guess it looks/feels better to “drop” down to gravel, than to go from WT road team to a pro-conti. He’s still a pro racer though.

Any comparisons feel like Merckx in the 1960s, on his way up. It’s one thing getting to the top, another staying there for so long and of course Pogačar has plenty of range but as good as he’s been, Vingegaard has beaten him at the Tour two years in a row. Which is why this summer’s Tour has been enticing for so long, even if our assumptions and expectations keep changing because of events.

Pretty much any professional sport these days has much more consistent athletes. As training has matured virtually any rider can make it to the peak or near that level they are capable of. This has reduced the average differences between riders compared. The tight control on eating means that the riders can across the board get to the lowest weight they can at full strength. All these things matter.

What i really mean is that if you could quantify the riders by strength the standard deviation would be much lower. A rider as many standard deviations from the mean as Merckx would be much closer to the rest.

So even if the Giro this year seemed to be weak compared to Pogacar this almost says more about Pogacar’s strength then the other rider’s weakness. Although yes most teams keep there best leaders and domestiques for the tdf

So Merckx dominated his time but it’s hard to say

The ladies racing is improving but still suffers a little from this lack of depth so a very few riders completely dominate almost all types of racing.

That tale of Merckx chasing down Van den Bossche, and the one you shared in the Giro where he picked a fight with someone over a crate of wine won at an unofficial prime (or something similar), makes him sound like a bit of a tit really.

I agree. He comes across as a thoroughly unpleasant person. Maybe he’s mellowed since then, but I much prefer a bit of respect from the top riders. See also: L*nce Armstr*ng.

Well, the guy wasn’t nicknamed “The Cannibal” for nothing! I think if you read the book you might come away with a less nasty opinion?

BigTex OTOH, IMHO is just a punk. I thought so from the first time I saw him, long before he became “Cancer Jesus” though I will admit to feeling a bit of pity for the guy when looking at photos of him laying in a hospital bed without any hair on his head.

Some on that below. I find (from far, and from indirect sources, of course) Hinault more unpleasant than Merckx, in a sense. Armstrong surely even worse, among other things because he didn’t even have the cycling class to “justify” himself.

I didn’t find he comes across so badly but clearly obsessive at times, possessive even with the yellow jersey (“it’s mine”) and the tales in this book benefit from the passage of time, if he stole people’s lunch they’ve since had time to get over it and so are happy to recount the tales, especially the moments when they could turn the tables from time to time.

There is a tendency for professional athletes & sports people to gloss over poor behaviour and downright bullying if the person in question is successful enough. Ultimately winning is what counts and that’s how they’re judged. It’s not the way I roll, but I’m just another middle-aged chap slumped on his sofa.

Highly recommended read!

I think the Merckx/Pogacar comparisons are off-the-mark. IMHO (and a few others) Fausto Coppi is a better one.

As to the rivalry stuff – how much of that was simply ginned-up by the press out of nothing-much?

The difference these daze may be that so many pros have media training and/or a press officer? I remember watching a BigMig interview along with a native Spanish speaker who claimed Mig’s translator was telling the TV guy stuff that Mig was saying that made Mig sound like a swell guy..while what Mig himself was saying was actually quite different!

The impression that I get is that Merckx was a better sprinter than Pogacar so his tally of victories is probably hard to catch.

Also, for how long will Pogacar ride? He will probably be able to get a job as president of Slovenia by the time he is 30!

Longevity is a big thing for many, Peter Sagan perhaps as an example of bursting on to the scene and then retiring in their early 30s.

I suspect a lot of the ‘rivalry’ back in the day was simply side effects from amphetamines and leaded petrol. It’s not something the sport particularly needs to be entertaining IMO (although if Pogacar and Vingegaard were caught sleeping with each other’s partners that would be an absolutely cracking scandal).

I don’t know, a little bit of needle is nice sometimes. I quite like that The Vans don’t share a kiss after every race. As I’ve said before Pogacar’s ‘I’m best mates with the whole world’ act gets wearisome I find, undeniably great rider that he is.

I prefer a no-needling policy.

Did any cyclists actaually get caught doing that in the past or is it just a hypothetical example?

There are still rivalries in other sports today but a lot in the past seemed to be mediated by newspapers where one rider would say one thing and the sizzling quote would be the title, this would be read in the newspaper the next day and the other rider asked for their reaction to this… and the incendiary response often followed. Today there can be more room for context, plus riders are trained (formally or just by experience) in what to say so as not to cause havoc etc.

I think it’s more a combination of toxic masculinity no longer being entirely acceptable socially, whereas back in those days being obnoxious and aggressive was (wrongly) seen as ‘men being men’; and also the huge influence of PR training on the riders: they’re told not to say this, that and the other.

The upside of this is that you can see that WVA and MvdP are rivals but lacking in animosity, without getting to the somewhat ridiculously chummy extent of some riders. The downside is you get someone like Roglic not admitting that he was trying to beat Kuss in last year’s Vuelta and coming out with guff like ‘I really hope he wins’, literally minutes after attacking him. If he’d been honest, I’d have a great deal more respect for him. People also talk about how Evenepoel has matured, etc. and that this shows in his interviews. Much more likely it’s the media training.

The other effect of the PR is that almost no rider interview is worth hearing – banality after banality. (Geraint Thomas is an exception, but there are few others.)

Oh, but I think that Rogla wasn’t actually unhappy if Kuss was going to win the Vuelta, although of course he’d have preferred to win that himself as the strongest rider in the race. His issue was rather with Vingo…

Seemed to me that Vin was happy for Kuss to win, albeit only after Vin had taken that stage and the time to make sure he came second overall. After that, only Rog attacked, while Vin followed.

It seemed obvious to me that Vin was the strongest rider in the race, and that had Rog got the open race that he wanted, he’d have come second. On the stage where Rog attacked Kuss and Vin just followed, it looked like Vin could have left Rog for dead were he actually attacking.

I think Rog is a spent force when it comes to grand tours. He might have lost the Giro last year had Thomas an ounce of attacking blood in his veins: on the day Thomas dropped Rog, he didn’t fully commit to taking as much time as possible. Had he done so, who knows.

Hopefully, we find out either way in this year’s TdF. (And personally, I hope Pog smashes them.)

My vision of that Vuelta is quite different, according to athletic conditions showed. But admittedly we’ll never know. Of course, Roglic is no match for Vingo both on equal level of respective form, but Roglic was way closer to a potential top than Vingegaard in that occasion. When Vingegaard went and took that huge lot of time it was very manifest that Roglic didn’t go with him obeying team orders and a supposed plan which didn’t prove very consistent at first sight (it was, if you consider that the team had decided to have Kuss as the final winner).

That giro was weird. Rog never looked great the whole race. Hanging on with the other top GC riders, but never looking like he was stronger, Thomas particularly. Then there was the stage where he looked /awful/, like he’d cracked, and got dropped, but – as you say – Thomas didn’t or couldn’t press home the advantage and Roglic didn’t lose much time (IIRC, he was down by more on that stage, but managed to regain a bit of time?).

Then 3 days later Roglic has the most amazing mountain-TT form ever seen. Thomas puts in an incredible performance, and yet Roglic puts at least a minute on him, given the chain drop – 40s on the line.

I struggle to believe that performance I have to say.

Paul J – how do you feel about the Dane’s amazing performance in LeTour 2023? The chrono where he took massive time gains on everyone after being unable to distance his big rival up to that point? Van Aert and Pogacar notch up some cracking performances only to be smoked by the Dane? Is that more credible than Roglic’s ride?

Paul J, I still believe the decision to go with MTB gearing had the biggest impact.

@Paul J

G’s performance wasn’t an “incredible” one. TDF 2023 was an outlier performance over an outlier performance, but Thomas’ time on Lussari at the Giro was extremely close to the rest of the GC top-5 on whom, according to expectations, he should have had a way broader margin. Just watch the second half of that ITT. It’s very manifest from visual clues that G was struggling more and more (probably due to wrong gearing, also) – which rarely brings good results in any ITT, let alone one which gets harder in the second half. He had the 5th time in the penultimate segment, even if it was (relatively) easier than the first part of the climb, and then the 15th one in the last section, where in some 1,500 flattish mts he lost 11″, more than of 25% of his total loss on the day and some 70% of what he’d have needed to keep the maglia rosa. Quite a disaster-ITT, frankly, given the athlete’s profile. Which doesn’t mean that Roglic hadn’t a great one, but your description above isn’t spot on, not at all.

Your interpretation of the final stages is totally misguided, as well. Roglic was clearly feeling better and better, as the results show. On the Zoldo stage he was dropping the rest of the best-men-group barring Thomas and on Tre Cime he already looked stronger than Thomas although barely so.

Ineos lost their occasion when they asked the stage reduction to reduce risks… risks fo their GC plans, I mean! But Roglic wasn’t yet well (probably some lingering illness rather than form) and they’d have put time on him, even if losing to other contenders.

I would extend this to say that no interview with an active sportsperson is worth any of anyones time.

Maybe, but Cecile Uttrep Ludwig is the exception that proves the rule. I still regularly watch her ‘Happy Dead Fish’ interview whenever I need cheering up….the changing expression of the bored podium functionary in the background is priceless…….PUT THE HAMMER DOWN !

https://www.bbc.com/sport/av/cycling/47868621

Evie Richards can give her a run for her money. Not very enlightening but a pure delight.

Different sport, but I remember coming across English lessons with Aitana Bonmati, one of those get-to-know-the-players fluff jobs. Funny and winsome off the pitch, lethal on it.

Then there’s Keira Walsh. Trying to figure out what she’s saying is half the fun.

Rémi Cavagna in this morning’s L’Equipe is a good read, his move to Movistar has been a disaster so far and he explains a lot.

It often depends on the format, a microphone at the finish line often doesn’t tell us much (“the team did a great job” etc) but other formats can work well.

Wow! And I’M the cranky cynic?!?!?! 🙂

To stay recent and within cycling, Mohoric’s (paradoxical, from the muting gesture to being so vocal). And I remember reading great interviews to Annemiek van Vleuten when she moved to Movistar (in this case, admittedly long form). And I’d surely find more examples if it was worth more of time to think about ’em ^___^

An active sportsperson must dedicated a lot of their time to, well, training, which maybe doesn’t help. And, feel assured, it’s not the only “famous” category which struggles with providing meaningful verbal content, including many usually associated with culture like musicians, some visual artists… writers, even! Plus, a huge responsibility for a mediocre interview is always on the questions asked, so… imagine that journos should be pros when words and questions are concerned, and yet!

“Plus, a huge responsibility for a mediocre interview is always on the questions asked, so… imagine that journos should be pros when words and questions are concerned, and yet!”

And yet….one might ask if there have ever been WORSE interviewers than what we get on English-language TV/streaming these days? IMHO in general they’re terrible: They rarely ASK a question, instead they make a statement of their own half-baked opinion on what happened and then try to get the athlete to confirm it. They almost never listen to whatever the response actually is in favor of the next “question” on their list.

I feel for the athletes and am amazed that they don’t say “Well I just explained that, you moron!” instead of patiently sitting there while the so-called interviewer blathers on.

As I noted recently, Merckx suffered early on from strong oppositions by different clans within the Belgian movement, at first it was more generalised than in later years but surely that contributed to forge his attitude – besides being the undoing of many a great rider, Maertens first and foremost. Curiously, this part of the story is rarely highlighted in the most common media versions, at least in Italy.

In contrast, the rivalry with Gimondi was real and bitter but still very respectful.

Others again became obsessed to beat Merckx and modelled their careers to go into that direction, De Vlaeminck being the best example. Eventually, that was probably good for him… and a strong impulse for the developing of a strong idea of “specialisation” between Classics and GTs (something which wasn’t new at all, of course, and wouldn’t become instantly general, either, but it was a landmark all the same because it was very “programmed”).

Ocaña was totally obsessed on a personal level, too, probably deeper than anybody else ever, and in fact that was the factor which made him able to physically overcome the Belgian… although…

Pure climbing talents often could have the better of Merckx, think Baronchelli or Tarangu, but they probably lacked the sheer, steady willpower and had other technical limits which made it hard for them to be a constant GC threat of sort.

These rivalries are quite well covered in the book, the difficulty of Van Looy accepting Merckx coming up; of how Fuente (Tarangu) probably could have won a lot more if he’d managed his efforts better and attacked on the final climb of the day rather than the first etc.

“The Stars and their Water Carriers” – film about the 1973 giro, is fascinating to watch. Fuente attacking the mountains and taking a good few minutes out of Merckx. In a modern context, a performance would like that would seal a GT victory, but Fuente couldn’t do it against Merckx. Indeed, Fuente couldn’t even crack the top-5 in the end.

The section on the flat stage where the bunch are just cruising along, joking with each other. One of the riders takes the microphone from the camera bike – Frankie Bitossi I think – and starts interviewing fellow racers in the bunch. Riders jokingly begging Eddy to let them win a stage.

Good watch.

And that’s a wired mic – the lead trailing over the bikes/riders back to the motorbike. 😉

Wasn’t the point about merckx victory at mourenx was that by then he was so far ahead on GC there was little point in attempting to chase him down once he’d got away?

I know he won a lot of local criteriums and, of course, it was a different era, but Merckx won over 500 races!!! Pogačar – much as I am a fan – will do exceptionally well to have half that many on his palmares when he retires.

I think Merckx is in a very very small group of outliers in sport who are incomparable – the only other one I can think of with similarly alien numbers is the cricketer Sir Don Bradman who averaged 99 runs an innings in test cricket, when the benchmark of being exceptional for a test batsman was, and still is, an average of around 50.

Marianne Vos

Genuine question – not being snidey, I have no idea: was Vos’ competition up to much back when she was winning everything?

Up to much, I’d say. The lack of depth affected the broader field but not the top quality athletes, which situation mainly changed race dynamics rather than absolute competitivity. The change in race dynamics can on turn favour this or that athlete, but this wasn’t generally the case given the lack of specialisation. We can check the above looking at those top athletes who rivalled with Vos and who, like her herself, didn’t lose winning manners even as the field gained depth while at the same time they were growing older. Longo Borghini is a good touchstone in that sense, but there are more like Ferrand-Prévot, Bronzini, Ashleigh Moolman, Spratt, Niewiadioma et al. Then you have the athletes whose career ended before they could be faced by the next generation but whose absolute athletic performances can be used as a test of sort, think Abbott, Pooley or Cooke.

All the above is a bit simplist but is an example more than anything.

You can only beat those who show up and pin-on a number.

Recently some clown claimed Merckx’ record wasn’t so special because his competition was a bunch of “cigar farmers”…as if Gimondi, DeVlaeminck, Maertens, etc. were just amateurs who showed up on a Sunday morning as pack fodder. Really?

Greg Louganis in diving, Eric Heiden in speed skating, Maureen Conoly in tennis, Babe Diderickson in golf are a few more .

I can never warm to the GOAT thing as athletes can only ever beat their contemporaries using the equipment of the time. On the other hand I have a soft spot for the trail blazers such as Walter Hagen in golf … which leads me back to Arthur Zimmerman.

Marshall “Major” Taylor

Usain Bolt is probably the only athlete this millennium to bear a similar comparison.

7 MSR. Just look at how Pogi the Almighty is struggling to win it even once.

Yeah, if anything that is his most impressive stat. To dominate the big race that is open to the widest variety of riders, and famous for being easy to finish but hard to win, in such a way is pretty staggering really. When you think De Vlaeminck won it 3 times as well. Nobody else got a look in for a decade!

So Oscar Freire is criminally underrated? Probably right?

Underrated by whom? Yesterday or so CN put him in their (quite absurd) top-10-sprinters-ever list. That list borders nonsense, yet it shows that Freire’s got his place in cycling history even for those who have a pretty much vague idea of history itself (besides being notoriously biased and not exactly in favour of Spanish athletes).

In Spain, he’s one of the more beloved ex pros, often interviewed by media.

In terms of results, Freire’s place in history is clearly below Sagan, but not dramatically so.

I believe that Pogi won’t ever come close to Merckx in quantitative terms, but the point above is quite silly, as it’s been put down…

“Look how the GOAT Merckx always struggled with Lombardia which he could only win twice out of nine participations, whereas Pogačar got three in a row with a 100% success rate despite racing often in mediocre form”. Pfffff… yeah yeah.

However, cycling was quite different, and one big change is very recent: racing *way* less (albeit nearly always with a very strong competitive angle in physical terms). I’m with Larry in assessing that it’s hard to define this a progress from *any* POV

(just like athletes tackling easier courses in stage racing

-____-)

If you race less, it’s easier to get high winning rates but harder to sum up total numbers. Lapalisse dixit.

There’s a lot more to be said of course. Just as a sample, you might notice that at the end of the day Merckx won most of his Sanremo when he wasn’t still/anymore as competitive in GTs. He still won 3 during his absolute prime, yet it’s telling that his whole career was shaped differently from Pogačar’s as at the end of the 1970 season he had “only” 4 wins in major week-long stage races plus 2 Giri and 1 TDF, but he already got 7 Monuments of the 19 he’d finally get… (4 of them once he’d stopped winning GTs for good).

It’s also notable that most of his Monument wins during his top GT years came from Liège and Lombardia.

And all the above in an era when systematic specialisation was at its very beginning and for an athlete who’s the most perfect symbol of all-around skills.

It’s sheer nonsense to compare. Pogi’s career could end abruptly (“facciamo le corna”) or he could race until, dunno, his 38. Quantitative comparisons really make very little sense, especially between a 25 yo and a full career…

Fair points, but I wasn’t meaning to compare, just to highlight the feat of winning the one monument where being an obvious favourite is so penalizing (ok, Flanders was, too, back then), 7 frigging times. Granted, the first time he did he benefitted, like Cancellara and many others, from his relatively unknown rider status. But not the other 6. He wasn’t as effective in Lombardia, sure. If you compare, it’s true that, like 150 Watts said, Pogi doesn’t have the killer super-long sprint Merckx had, whereas Pogi has probably more of a climbing differential over his rivals (Vingegaard excluded), than Merckx had in his day. Anyway, seven Sanremos, won in very different ways (and even passing on racing it in two of his best years) is a a really mean achievement by any standard.

Copied across from the previous incorrect posting.

Well, for the doubters Merckx will take some beating with his truly well rounded record:

5 Tour de France, 5 Giro d’Italia, 1 Vuelta, 7 SanRemo, 5 Liège–Bastogne–Liège, 3 World Championships, 3 Roubaix, 2 Lombardy, 2 Flanders, 3 Flèche Wallonne, 3 Ghent-Wevelgem and more than 200 other races.

Pog is going to have to up his game!

Meanwhile, Fausto Coppi has “only” 87 wins according to PCS. But a) look at the list as far as quality vs quantity b) remember there’s a 4-year gap in his 17 year career for WWII.

OTOH I doubt whether Pogacar gives a rat’s a__ about any sort of records. Seems he’d like to do the double + win the World’s in the same year and maybe add the Olympic road race title while he’s at it. I’m guessing that would make him unique, but it’s certain there will never be another Merckx.

W Il Cannibale!

Completely off topic, but I’ve just read Remi Cavagna’s complaints that he has problems after moving to Movistar because “they all speak Spanish”. I think this is hilarious, did he not foresee this?

Ya wonder. What did they tell him during the negotiations before he signed? Reminds me a bit of the Netflix mock-u-series with their bits on Ben O’Connor on the French team – couldn’t help but think back to “26 Days in July” with Phil Anderson’s trials and tribulations as an Aussie on a French team.

There’s always gonna be that team dynamic, no? If they don’t much like the guy they’re gonna speak in slang/dialect so he never really knows WTF is going on. And even if he learns it all, he’ll then just KNOW when they’re f__king with him instead of just thinking they are?

But if you understand the language you may gain the upper hand by continuing to pretend that you don’t. Judicious application of knowledge gained from overheard gossip is the best way to burn your

enemiesteammates.If the NetFlix mock-u-mentary is to be relied on, Ben’s mostly looked after at AG2R by a native english-speaker – Ass. DS Stephen Barratt, an Irishman.

And Aussie and Irishman should be reasonably close culture wise too. 😉

For whatever reason it didn’t seem to be working in the scenes I watched so…

I remember driving some Irish guys to the airport in France once…gotta say we were two groups of people divided by a common language…could barely understand a word they said! Aussies OTOH I don’t have too much problem with.

Have you watched the thing? O’Connor seems to have a tough time understanding the French the DS is speaking while that Irish guy seems kind of a sidekick to the real management. AG2R seemed pretty French in the mock-u-series that I watched last week. The Irish guy did such a great job O’Connor’s moving to Jayco.

Sure, my point is I don’t think Ben (or anyone) can totally blame it on language issues – a lot of his contact with sports management was via a native english speaker! Also, it seemed Julien Jurdie was happy to speak English with Ben.

I’m just saying it wasn’t really language issues. 😉

Where did I claim it was purely language issues? I relayed my memories of “26 Days in July” which wasn’t solely about language issues. But the mock-u-series made it seem that a lot of O’Connor’s issues on that team came from his failure to understand the language well enough…which goes back to the Cavagna bit that started this whole diversion from the Merckx book. OK?

A little silly on my part to comment not having read the interview, but couldn’t he ask Aude Biannic as a French rider with a long and successful stint on the women team? I also know they actually use English sometimes on the male team (Spanish speakers are a vast majority but they long had native English speakers as athletes and staff).

Ah the ol’ good times when the international peloton was speaking… Italian 😛

Cavagna could do a masters degree in Spanish language but once he gets to a race and has a crackling radio full of “repechos”, “rompepiernas”, and instructions with idioms like “go with the hook because we might see fans on the exposed section ahead” to use the literal English translation, well things get more complicated. A tip for anyone racing in a new country is to learn these phrases almost first alongside hello and thanks.

His L’Equipe interview was a good read because he’s so candid about all the issues he’s had with his position, his bike, his saddle and team management, a real “cagada”… when others would be more discreet.

But that’s also what makes it easier, really 😉 You don’t need to master the whole language, probably not even knowing the meaning of the words, just what… they aren’t meant for! It’s like when as a fan you watch Sporza without knowing Flemish.

I find it a bit poor when people go to the media complaining about *a team*, especially when you can have comparative success stories under different angles. At best, it’s a mismatch, a mutual mistake rather than the sort of blame fest some athletes indulge in. Looks more like excuses (maybe well-intentioned, like the athletes really believes in it… maybe…) to account for poor performances – or a sudden jump to high performance when you eventually shift teams – that are really down to other more complicated factors.

Ya wonder what all the whining is gonna do to improve the situation? Ben O’Connor’s changing teams for what seems like a much better fit while Cavagna seems to have gone the other way? Trying to think of non-Spaniards who have done well/been happy at Movistar…and drawing a blank.

Athletes from South America tend not to be very happy, but they usually do well there, think Quintana or Carapaz as the most obvious and recent ones. One can conjecture that they’d have won even more if they had received more respect, but all the same they won big there. Amador also had a very good career there. Italians tend to be happy there although not perfoming great, mainly because they take it as a career ending transition before retiring, but things are usually clear both for them and the team with mutual satisfaction (spending several seasons together). Think Bruseghin or Bennati. Good feelings and good performances for Malori until he suffered that freak accidents, when the team showed one of his strong points compared to most of the rest, i.e., the human factor. Visconti also had decent years there from several POVs, albeit with his usual up and down. Same for Portuguese like Rui Costa or Nelson Oliveira.

But maybe you meant not-native-speaker-of-any-Romance-language. In that case, well, Kiryenka performed well enough to be bought by Sky for their super team, Alex Dowsett had most of his victories (and by a long way) whike racing there, Sütterlin was built into a very consistent gregario by them. More recently, Mühlberger and Barta look like they’re very happy there and very solid in doing their thing.

Obviously, they don’t have a huge budget and they are like a family, or directly “a family” (as in Unzué Dad & Son), for good or ill. “Families” have their downsides, too.

Good points. After I posted that I thought more about it and came up with a couple of names that you mentioned, but in-general it seems a team for Spaniards….whether they can deliver the wins or not – Enric Mas being example #1

@Larry, yes, for sure strongly a national team, although Telefónica was privatised, as a strategic once public national company, it still keeps lots of contacts with State powers and abroad the Spanish State considers that Telefónica’s interests are its own (same as Monsanto for the USA and many other examples).

Which is why their attitude towards Latin Americans can also become so ambiguous sometimes.

National athletes always have a protected status in any team, but this is on the upper range along with Lotto for Belgian, Sky, the French teams in general etc., (probably even above Astana!).

Similarly, sometimes you end up suspecting that some talented cyclist would perform better out of that “national” confort zone, although it’s generally an advantage for the athlete.

In Italy something solid along those lines is sorely missed. You don’t need 2-3 projects like that as in France, but perhaps just one…

Of course after Liquigas and Lampre “we” still had half Astana, now some Lidl-Trek and half UAE, but it’s not the same. Not that it would solve Italian’s movement structural issues, anyway.

As I noted, Phil Anderson on the Peugeot squad came to mind watching O’Connor seem out-of-the-loop with the DS’ at AG2R.

Gotta wonder what Cavagna thought he was signing up for? Hard to believe there’s not enough word-of-mouth about environments on various teams for him to sign up blind and end up whining about everything if the reports on this piece are true….as if that’s gonna fix it.

“I know first hand they have great personalised follow up by one of the biggest specialised saddle brands on the market (leveraging on revenues which are closer to those of bike manufacturers rather than components industry), so I wonder what the “issue” might have been, given the number of anecdotes I’ve known about them going huge length to make any single sponsored athlete happy with this subject.”

Few things are more subjective/personal than saddles though I’ll admit some can just sit on anything and be OK (I hate them!) so matter what whiz-bang, 3D printed, bespoke thing their sponsor might have come up with, perhaps the guy just wasn’t comfortable and upset they wouldn’t just let him use what he was used-to and throw their logo on it? It’s not like that’s never been done before and my guess is still being done a lot more than Joe/Jill Crankarm would believe when they’re down at the shop to buy whatever they think their hero uses/endorses?

What season are we racing in the “mock-u-series”? 2023? If so, then it is a bit puzzling why O´Connor should be unhappy with a Fizik saddle – after riding the two previous seasons on Fizik saddles?

My impression is that he started the 2023 as the team´s main GC hope, but found himself playing a minor role compared with Felix Gall. It could be the main motivation behind the move to an Australian-speaking team is to be found in that general direction?

PS I´ve never met a fellow rider, youthful or middle-aged, competitive or wannabe, who had bought a saddle of a certain brand because the team of his or her “hero” was sponsored by that manufacturer…

Not sure about your use of “cagada” here, in context it would be here understood as “a serious blunder”, which was maybe what you wanted to say, but I’m not sure as it feels strange, like you really referred to letting the cat out of the bag or overstepping the mark, or a mix of those. In Italian it would be perfect “farla fuori dal vaso” which might remind indeed “cagada”, only in Spanish it works a bit differently.

Besides that, may I ask what did Cavagna say about the saddle?

I know first hand they have great personalised follow up by one of the biggest specialised saddle brands on the market (leveraging on revenues which are closer to those of bike manufacturers rather than components industry), so I wonder what the “issue” might have been, given the number of anecdotes I’ve known about them going huge length to make any single sponsored athlete happy with this subject.

(And, no, I don’t work for that brand ROTFL)

C’mon Monday – keep up! The saddle thing was part of the Cavagna whining in L’Equipe. Nothing to do with O’Connor other than I brought him up after watching the mock-u-series and noting it was similar to “26 Days in July” in that a guy seemed out-of-place on that team, same as it is with Cavagna and his team.

All this is far away from the Merckx biography guys. Will close the comments soon.

Bit quiet here but work behind the scenes for what’s to come soon…

I stand corrected. My mistake, no denying it, even if it was a mistake that I might not have made if your reply to gabriele had been where it should´ve 🙂

PS Here´s hoping the discussions in the (real soon now) coming three weeks will not be too much about the GC riders people (for any reason) dislike and more about the (GC and non-GC) riders (and other things) they like.

Apologies, M. Inrng, I never intended to derail the discussion. Mea Culpa…