Federico Bahamontes has died aged 95. A true king of the mountains, he was the first Spaniard to win the Tour de France, a famous ice-cream eater and a self-styled relic of the good old days.

He was born Alejandro Martín Bahamontes in 1928 in Santo Domingo-Caudilla near Toledo, Spain. Normally he’d have been named Alejandro Martín but got his mother’s surname as there were too many other Martíns in the village, then he took his first name from his uncle “Fede”. This was just the start of his quest to make a name for himself.

If glory and riches were to come, Bahamontes’ childhood was spent in poverty and amid war. Literally dirt poor, his father was a road worker who “crushed stones to make roads, like in those prisoner movies” Bahamontes told ABC and he was born in a caseta, a roadworker’s hut. But worse was to come as Spain’s civil war saw the family destitute in a refugee camp. Alasdair Fotheringham’s biography “The Eagle of Toledo: The Life and Times of Federico Bahamontes” details plenty, like eating “baby goats”, the euphemism they gave to stray cats that Bahamontes would catch and his mother would skin and gut to put meat on the table, along with bits of dried fruit and vegetables scraped off market stalls and truck beds.

Bahamontes started cycling because of necessity. He got a job in a bike workshop and worked as a delivery boy but upped the distance on his father’s bike to smuggle food. He’d do 50-60km a day to pick up supplies from farmers and others which, after dodging any police checks on the ride back, his mother would then sell on the black market for double the price. Being hungry was something he later credited his success as a cyclist to. While rivals chewed on steaks ahead of a big stage, he felt he only needed a handful of dried biscuits washed down by tea. He said this made him lighter for the climbs.

Aged 18 he saw a bicycle in a blacksmith’s workshop and paid 30 duros and started racing, encouraged by fellow black market bicyclists impressed by how he could ride an iron bike. Money was a bigger incentive than sport, his parents agreed as prize money could beat what he could earn elsewhere. He was going to climb out of poverty in more ways than one.

Success on a bike seemed to come easily, at least reading the palmarès where as an amateur he started to win the mountains prizes in professional races. He won Madrid-Toledo in 1952, or at least crossed the line first but as he had independent licence he was not considered a professional and so the win was given to someone with the right paperwork. He had it the hard way, cycling to the start of races in Spain while rivals went by car or train. Another champion of Spanish cycling from the 1950s Miguel Poblet told El Correo about the first time he saw Bahamontes, “suddenly, pedalling next to me, I find this scrawny boy, dressed like a homeless man”, adding “he rode away from us”. Jesús Loroño noticed something similar too, there was no vision of a future rival, instead he saw a bum, “he was stretched out under a tree licking a piece of bacon and looking like a tramp“.

Before he could turn pro he had two years of la mili, military service, then in 1953 joined French team Splendid, backed a frame builder. He was asked to ride the Tour de France that year with the Spanish team but turned it down after consulting with his mother, one of the reasons cited was he didn’t own a suitcase. He’d start in 1954 but if he was a professional, it was far from the status enjoyed today and he was still cycling hundreds of kilometres to the start of races as he couldn’t afford to travel by any other means. That year the Tour organisers supplied riders with two suitcases each but he didn’t have anything to put inside. Still he won the mountains prize in his first attempt and enough prize money to buy all the luggage he’d ever need.

Rivalries and duels were all the rage and while Italy had Coppi e Bartali, for years Jesús Loroño was Bahamontes’ arch rival, at least in Spain because Loroño didn’t often race beyond the Pyrenees even if he did take the mountains prize in the 1953 Tour de France. Trade team mates in 1953, they’d go separate ways but as the Tour de France and Vuelta a España were ridden by national teams they’d be forced to cohabit in these grand tours and the duel reached its apotheosis in the 1957 Vuelta. Later Julio Jimenez took over the rivalry, a personality clash with Jimenez who’d run a brothel in retirement while Bahamontes owned a small bike shop. Such rivalries were the bread and butter of newspaper coverage of the sport.

Bahamontes rode in a time were television started its takeover but his early years belonged to the print era and this includes the myths that went with it, notably him stopping for an ice cream at the top of a climb during the 1954 Tour de France. Several accounts say he stopped at the top of the Col du Galibier, others that it was the Tourmalet and being wary of descending by himself he preferred to wait for the company of others. It’s true he was never a demon descender but this story is less romantic and more pragmatic. On Stage 17 the race went into the Vercors and Bahamontes was instructed to win the day’s first mountains prize and he took off up the spectacular Gorges des Ecouges and was first to the Col de Romèyere for the points but he broke two spokes and it’s here that he waited for the Spanish team car as bemused spectators treated him to an ice cream.

If the myth of a whimsical climber waiting alone atop a pass stuck, it’s in part because Bahamontes helped sketch the image of just what a mountain climber is in cycling: a solitary figure out in front of the pack: leading yet often accompanied by frailty and a loneliness. As LeMonde’s Alex Pedro points out, to write “Spanish climber” is a pleonasm because at times it feels like all Spaniards are climbers. Of course you can go from Miguel Poblet to Oscar Freire via Miguel Indurain and plenty more. Yet Bahamontes leads the line in Zorro-like Spanish cyclists who’d dart up climbs. A genuine icon with his wavy hair and bent elbows, he set the bar against which the likes of Julio Jimenez, Luis Ocaña and José Manuel Fuente were measured, and then Alberto Contador and probably Juan Ayuso.

Often though things were much less romantic. If he won the Tour de France in 1959, his story was also all the ways he lost the race too. He returned in 1960 and fell ill. He’d left in 1957 after an injection of minerals had gone wrong, leaving an arm and hand swollen. Yet many times he wasn’t interested in the maillot jaune, it wasn’t his thing. 1956 was an open edition with Gino Bartali, Fausto Coppi, Ferdi Kubler, Louison Bobet, Hugo Koblet and Jean Robic all absent for varying reasons. This left the climbers Bahamontes and Charly Gaul as pre-race favourites, albeit on a less mountainous route. The Eagle of Toledo had his feathers plucked on the opening stage when he lost minutes on the stage to Liège and would lose more again on the flat, Gaul too and the pair ended up duelling for the mountains competition as a consolation instead with Gaul winning this, while Roger Walkowiak won overall, his triumph berated by some at the time because he didn’t have a direct contest with the likes of Bahamontes.

The 1959 Tour de France saw tables turned. While Bahamontes and Loroño had divided the Spanish team in previous seasons, this time the French team was fractured. Bahamontes started the season on Fausto Coppi’s team, the Italian having retired to the team car and then the Spanish team was run by Dalmácio Langarica, also manager of the KAS team and this guidance counted for plenty. Henri Anglade turned out to be the strongest rider in the race but he was on a French regional team with the main French team keen not to be upstaged by one of the régionaux. This culminated in the stage to the Aosta valley in the Italian Alps where Anglade was away and virtual race leader because Bahamontes was dropped. Only the Spaniard found Jacques Anquetil and Roger Rivière bridge across to him and share the chase, for the sole reason that if they were not going to win they couldn’t be upstaged by Anglade. Yet if all this sounds like Bahamontes triumphed because his rivals were locked in petty squabbles it’s only partially so, he took time on the flat and rode a much more controlled race, it was this method that put him in yellow in the third week.

In 1964 Bahamontes played a key role in the race, his attacks teased out Raymond Poulidor and Jacques Anquetil and he won the mountains competition for the sixth time in a contest that lasted until Stage 21 where Bahamontes sent team mate Joseph Novalès up the road early to take the mountains points at the Côte du Cratère and thus keep Jimenez at bay. Bahamontes finished third overall too.

The Tour de France helped define Bahamontes. He never won the Vuelta, even if he collected stages and the mountains competition twice in his home tour but the triumph abroad was a result for him and also embraced by Spain, both the people and the Franco regime. He was even allowed to pedal on the grass of the Bernabéu, the Real Madrid stadium.

The “Eagle of Toledo” name came from France. This might be the perfect moniker, evoking both a creature that could soar high in the mountains but also a sense of place, and more noble than the “Flea of Torrelavega” name for Vicente Trueba, the first to win the Tour de France mountains prize. It was a label created by Tour de France director Jacques Goddet, as such l’Aigle de Tolède more than the El Águila de Toledo but the name stuck. It helpfully displaced the “Gypsy” label some of his peers had given him because he’d bring back spare parts from France to sell to cyclists in Spain, and “El Lechuga“, on account of him being so thin he was transparent like a lettuce leaf.

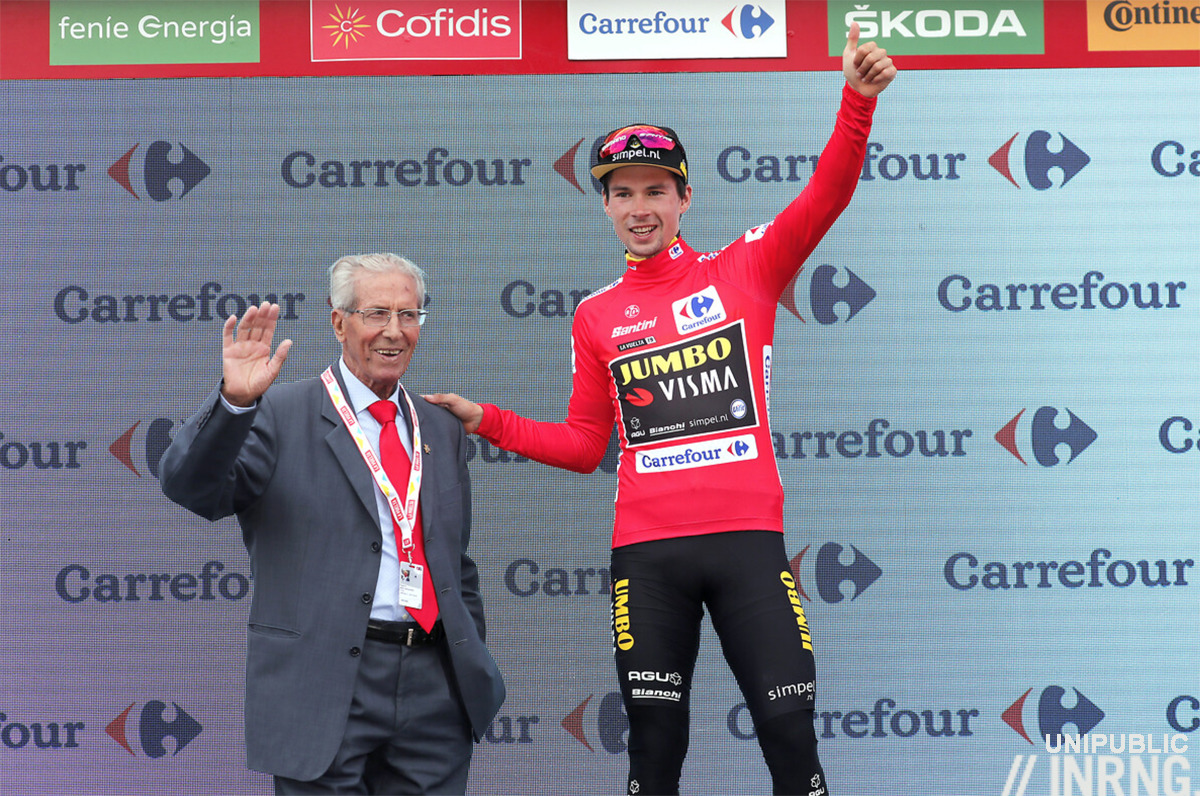

In 1956 he married Fermina and they stayed together until her death in 2018. At first he was running a bicycle shop in Toledo, then also a farm nearby with almond and olive trees. He was also busy promoting Bahamontes, he didn’t walk away from the sport but stayed as a race organiser and a regular visitor to the Vuelta a España and other races, an Iberian Poulidor for the way he remained visible and cherished the limelight. Aged 91 he was shaking hands with Primož Roglič on the Vuelta podium.

In retirement Bahamontes could still launch stinging attacks. He branded today’s riders soft because they got showers and massages. As the six time winner of the Tour de France mountains competition, he was asked by the L’Equipe what he thought of Richard Virenque’s seven polka-dot jerseys:

“He doesn’t even come up to my ankle. I hope he doesn’t mind, but if he’s a climber then I’m Napoléon“

He became the oldest living Tour de France winner after Roger Walkowiak died in 2017, a statistic, an anecdote but a burden too given the implication as if a bell was ringing out his final lap (something that now tolls for Jan Jannsen). Bahamontes though seemed to be made from stainless steel, he was a lively presence in old age, something he put down to avoiding doping, telling Max Leonard in “Higher Calling” that “all the people who raced with me are now dead because of what they were taking“. Luck and genetics helped too but it was vintage Bahamontes: any writer visiting the Eagle’s nest in Toledo would leave with a zinger in their notepad or dictaphone. To retell a golden age story in his office above the shop – complete with portraits of himself on the walls and a stuffed eagle – was to burnish the tale, strict historians might spot the polish applied but he was said to deliver stories with a wink and a nod, it was fun for him. He enjoyed the good old days and liked nothing more than to watch retro newsreels of his triumphs and recount his best days. He was delighted by a restaurant dinner with five-time Tour de France winner Miguel Indurain where at the end of the meal a waiter came over and looked at the two champions and asked for an autograph where upon Indurain smiled and nodded, only for the waiter to say “no, him” looking at Bahamontes.

In 2018 he took part in the unveiling of a statue in Toledo of himself. Usually memorials are commissioned posthumously but Bahamontes enjoyed a motorcade procession through Toledo recreating his triumphant 1959 Tour parade and then delivered a long speech under a scorching sun that had people half his age wilting. In 2013 L’Equipe called him the greatest ever climber. You could debate this but Don Federico used to boast “I won all the mountain classifications of all the races that I finished” and that’s hard to argue against.

Thanks for the obit – a sad passing of a champion from a distant era. Condolences to family and friends.

So childhood hardship, a long and happy marriage, bacon, biscuits, cat meat, ice cream & no substance abuse are the secrets to a long and fulfilled life, apparently. Feel like his generation could give mine a much-needed reality check.

What a touching obituary and a nice look back at a distant era. One of many reasons I follow IR.

Bahamontes Jimenez, Ocaña and Fuente seem the classic Spanish climbers too, brilliant but fragile, and far cry from the more reliable and stronger Contador. Fuente was my first monochrome sight of the classic KAS jersey.

Thanks for a lovely obituary, teleporting us back to another world.

Great story.

“No him” – outstanding!

An incredible tribute to an incredible racer who ultimately lived a great life.

Many thanks as always for your great writing, especially about the history of the sport.

It’s nice to explore these characters and their racing, with Bahamontes this piece almost writes itself, there are so many great anecdotes to share.

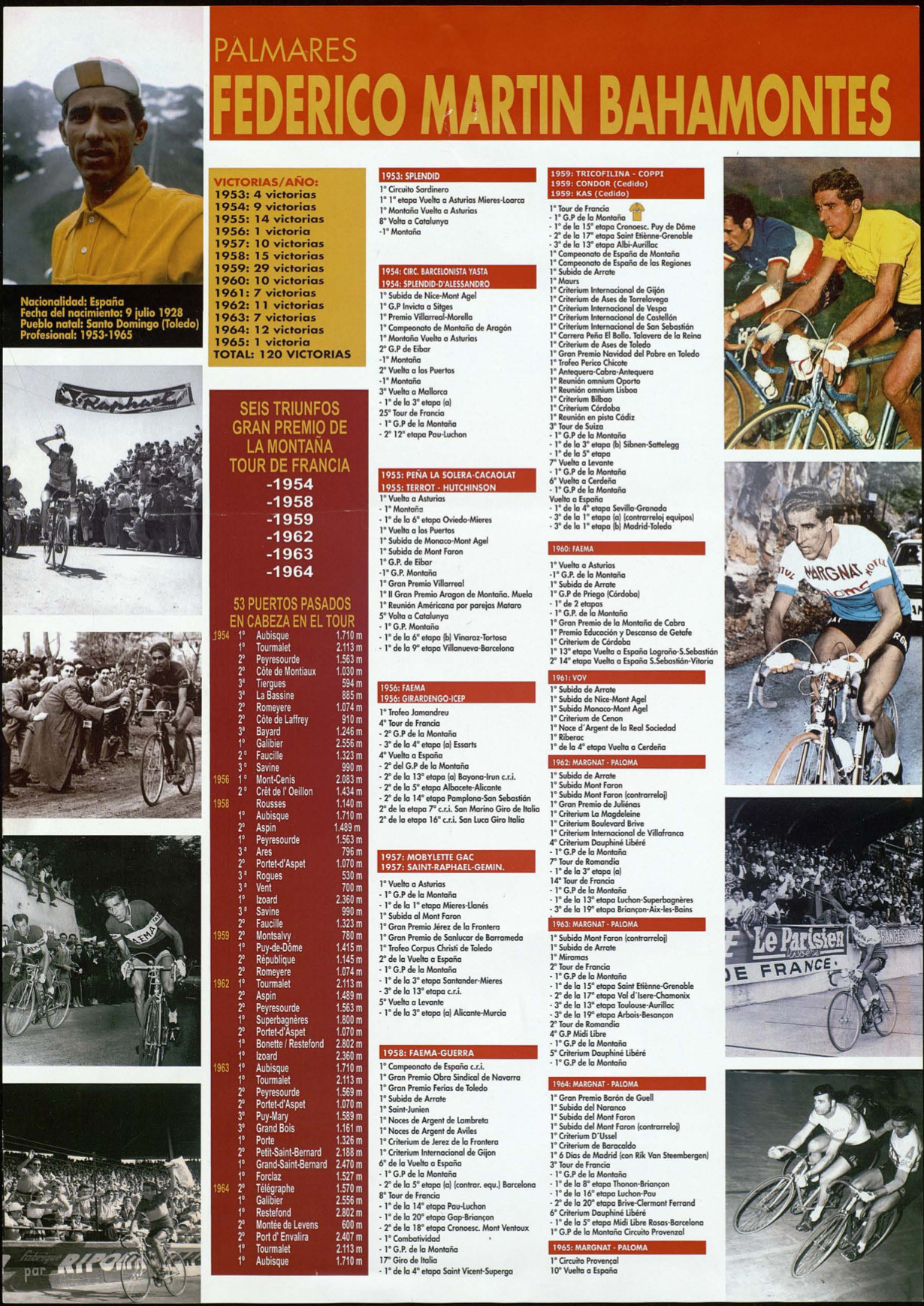

By the way the palmarès graphic is from Toledo’s town hall website, the piece was long without going into all the triumphs but he won the mountains competition in the Vuelta, Giro and Tour and so much more.

Gtreat potted obit. I feel I don’t need to read Alasdair Fotheringham’s book now!

It details plenty more of course, it covers so much, is well-researched and is a good read.

Thanks for this and your other moving obits of the greats. My knowledge of cycling history is deeper and richer from reading them.

That was a fantastic read, thanks so much.

Masterful, moving piece. Thank you. 10+ years of reading your blog and you still shock me sometimes with the quality of your writing.

Yep, i always have to check in for these gems.

Thanks for the many years of cycling elegies.

I read somewhere that his Puy de Dome climbing time was pretty close to what the good pros were doing in the TDF on the same climb this year… Amazing considering the advances in equipment, nutrition etc.

I found it here: https://twitter.com/faustocoppi60/status/1684656265882914816

🌋 Puy de Dome (12,5 km@7,7%):

2023: 32:56 Pogacar – RECORD

1959: 36:15 Bahamontes

2023: 38:00 Woods

Puy de Dome was not ridden in the EPO years.

Pogacar beats Bahamontes by 3min – not much when you think about the equipment differences.

That’s just incredible, regardless of whether Bahamontes did it as a mountain TT, given he would probably have had something like a 40×24 as his lowest gear!

That stuck out for me as well, but IIRC the Eagle’s time was for a mountain time-trial, rather than at the end of a stage.

It’s a fascinating ‘what if?’ though, to consider how he would do with modern kit and training.

The piece was long enough already but in retirement one of the things he loved was to see today’s races revisit the places he raced as it would remind him of his experiences on these climbs.

I think he might also have loved Strava as he really liked to climb as fast as he could and to prove it to his peers.

Impressive time indeed, mostly taking the material into account, and the gearing too.

What impressed me the most on Baha’s archive videos, is his style of climbing. He still looks very « souple » despite of the gearing of that time. He is quite relaxed on the bike.

Pure climber style.

thanks for that excellent obit. Some wonderful anecdotes and a feel for how tough he had it in his younger years . Alasdair Fotheringham’s book is definitely worth a read if you can get hold of it.

@inrng Thanks for marking the moment

Eagle indeed.

Great piece and tribute. Thanks for pulling that together, it was really enjoyable and informative, like the rest of your posts.

Thanks, this is why I love this blog so much!

I guess you meant *canyon* des Écouges and col de Romeyère?

Or the Gorges des Ecouges. I did think there was a col on the way to to the Romèyre where the cliff top section ends by waterfall but stand correct. It’s a fantastic bit of road either way.

The tunnel at the top of the Ecouges (mainly unlit) is pretty scary.

It’s a very unusual experience as it’s completely dark, go in 50m, 100m and then you can’t see anything, dark doesn’t do it justice, you can’t hear or smell your way out either. But it seems they’re doing works to put lighting in. I imagine Bahamontes and the Tour took the narrow cliff edge road in the daylight rather than the tunnel.

Scary dark even with half a dozen bike lights. Especially where the walls retreat at the couple of “passing spaces”. The Vercors is great for these roads carved into the limestone cliffs – some as balcony roads.

Each time I go back you hear talk of re-opening the Grands Goulets as a cycle track. But you can understand why some of them were closed because the maintenance bills must be horrendous.

One part I’ve never made it to is the Mortier tunnel, built for the Olympics, but abandoned because of perpetual landslides.

Bahamontes’ always been one of my favourite characters out of cycling history. The romantic climber.

If now the oldest living tour winner is Jan Janssens (1st dutch to have it), then the second oldest is Eddy Merckx.

Very nice obituary, lot of this was new to me. I espcially like his Napoleon quote, and the fact the he won every KOM jersey in the races he finished.

The good old days..