“They stole my Tour, they’re bastards“

That’s 1956 Tour de France winner Roger Walkowiak talking about the Parisian newspapers who criticised him for winning the race. To this day “winning à la Walkowiak” is a term used for an easy or an unexpected win, often in cycling but sometimes beyond, a French politician can triumph à la Walko too. With Paris-Nice passing by the city of Montluçon today, birthplace of Walkowiak, it’s a good day to correct this phrase. What if à la Walko really meant to take an impressive win at the end of a great race?

Find a map of France, put your finger in the middle and you’ll hit Montluçon. It’s here where Roger Walkowiak was born in 1927. He celebrated his 89th birthday last week and now lives in nearby Vichy. The son of a Polish factory worker and a French mother, Roger grew up in Montluçon when it was a busy industrial city and children used to race bikes around the town.

He joined the Dunlop factory club. The rubber company has long been the town’s biggest employer and today its crumbling factories are still visible. Walkowiak enjoyed success in the amateur ranks then did his military service. On his return he struggled to find work and started repairing bikes and racing, doing enough to turn pro for the Riva Sport-Dunlop team.

Walkowiak’s first pro season in 1950 was not an auspicious start, he caught a cold six times in five months. Things improved in 1951 and in a stage of the Circuit des Six Provinces – an event later merged into the Critérium du Dauphiné – he crossed over the Col de l’Epine first before the descent into Aix-les-Bains only to get beaten by Gilbert Bauvin, a name who’d become a thorn in his side later. This and more was enough to get him a ride in the Tour de France. While the sport had its nascent trade teams the Tour picked national teams and regional teams from France. It sounds parochial but it reflected the supply of riders as almost the entire the peloton came from France or countries along its border; plus the Netherlands and minus Germany. The British were seen as exotic and got the media coverage we see applied to Chinese or Japanese pros today; in 1956 the sole British starter Bryan Robinson, invited by a French regional team, was labelled “Phileas Fogg” by the media as if to suggest how far he’d travelled.

Walkowiak’s career progressed with a win here or there and some solid places like second in Paris-Côte d’Azur which we call Paris-Nice today and a top-10 in Milan-Sanremo. His ride in the 1955 Dauphiné impressed many, he was almost the equal of Louison Bobet, then France’s best, on all the main climbs including Mont Ventoux and finished second overall. But he never made the French national team for the Tour de France. Bobet himself said Walkowiak deserved a place in the national team. Yet he wasn’t picked for the French team and rode for regional Nord-Est-Centre team run by Sauveur Ducazeaux and abandoned on Stage 11 with a saddle sore.

1956, the big year that nearly wasn’t

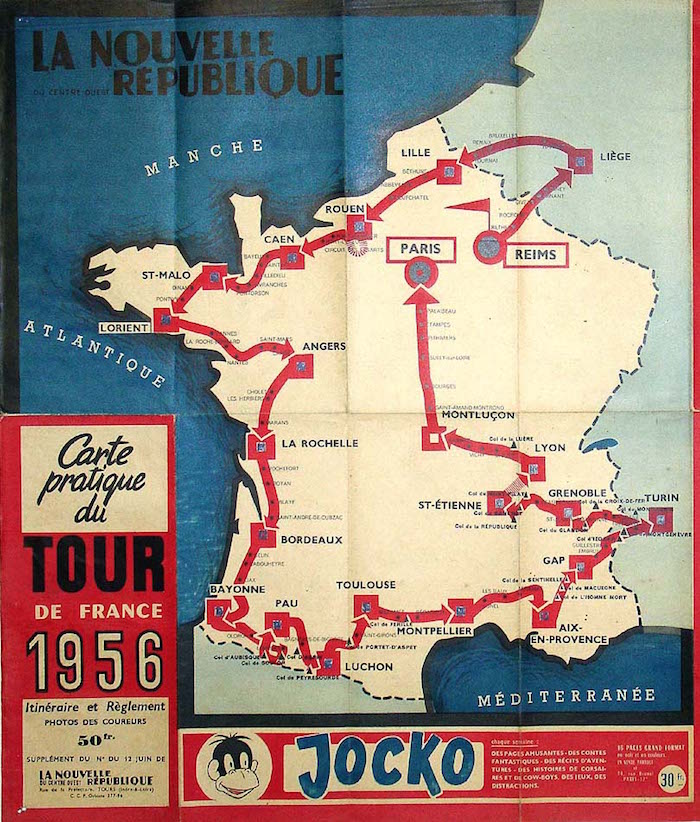

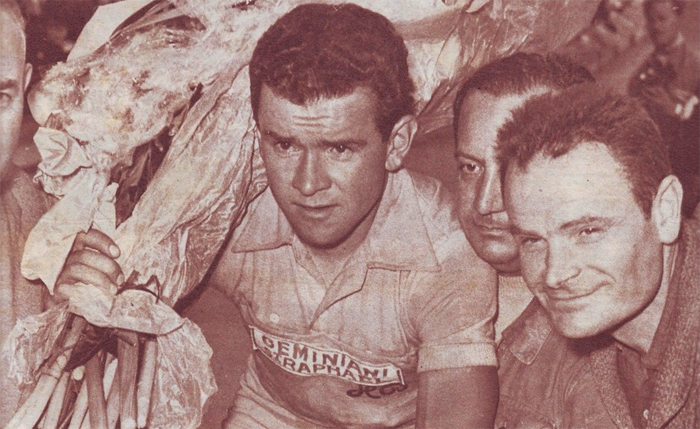

Walkowiak may have won the 1956 Tour de France but merely starting proved awkward. Earlier that year Sauveur Ducazeaux was managing the French team in the Vuelta a España, then run in late April, and he picked Walkowiak. Things started well with a team time trial win and then a stage win for “Walko”. But their leader Bobet wasn’t having a good Vuelta and pulled out. Other French riders quit and Walkowiak joined the exodus, taking the train home one morning instead of starting the stage. Ducazeaux blew his top and swore he’d never select him again. Come July and Walkowiak missed out on the French national team and qualified for the the regional Nord-Est-Centre team… managed by Ducazeaux. It took the intervention of Raphaël Géminiani and a handwritten apology by Walkowiak to start the race. He started but others did not, with Gino Bartali, Fausto Coppi, Ferdi Kubler, Louison Bobet, Hugo Koblet and Jean Robic all absent for varying reasons. Federico Bahamontes and Charly Gaul were tipped to win but the two climbers faced a less mountainous route ahead of them.

The race began as predicted with André Darrigade of the French national team winning the opening stage in Liège, wearing yellow and burying his rivals. Bahamontes, the Eagle of Toledo, got plucked alive and lost 30 minutes on one flat stage; Gaul surrendered 10 minutes on another flat day. Walko meanwhile was regularly at the front of affairs and Stage 5 placed one second ahead of a group of 20 riders who’d all put ten minutes into Bahamontes and 15 minutes into the field. The next day Walko made another breakaway that put over five minutes into the next group and 11 minutes on the bunch.

Stage 7 was the decisive day. On the roads from Lorient to Angers Walkowiak infiltrated a breakaway of 35 riders that finished 18 minutes ahead of the bunch led home by a dejected Darrigade. While Italy’s Alessandro Fantini won the stage, Walko took yellow, not only did he finish far ahead on Stage 7 but he’d built a lead from being in the other successful breakaways in the race already and was the best placed of all the 35 riders in the move. Walko took yellow that day but the story was the “Waterloo” of the French team, their crushing loss rather than the regional rider’s gain. L’Equipe’s Antoine Blondin, the playwright who chronicled big sports events for them, labels Walkowiak a “poujadiste égaré dans le Bottin mondain” which almost impossible to translate but think of a “petit-bourgeois lost among aristocrats” and either way Blondin mocks this modest rider leading the great race.

Walkowiak was part of this maxi-breakaway but so were Belgian Jan Adriaensens and Dutchman Wout Wagtmans and they’d go on to each enjoy a spell in yellow as Walkowiak lost time on them in the Pyrenees. He got his climbing legs in the Alps and, over the Izoard, matched the best that Bahamontes and world champion Stan Ockers could throw at him and the next day in the Alps he took back the yellow jersey and rode into his home town of Montluçon in yellow. He faced more attacks and Gilbert Bauvin was closing in especially when Walkowiak crashed and had to chase on the stage to Lyon. Even the last day wasn’t easy. These days it’s a victory parade but in 1956 they rode from Montluçon to Paris, today a four hour car journey and back then it meant a stage that lasted over 9 hours. “Bauvin and Adriaenssens attacked me 20 times” said Walkowiak. Whether the count is exact we don’t know but it shows the fight went to the end.

Walkowiak won his Tour and if the win was unexpected the result was settled. L’Equipe praised a powerful Walkowiak who rode better than everyone else in a lively race. Here’s Blondin again in his final column:

“The most athletic Tour de France we’ve ever known… …A moral ending fit to give satisfaction to every reasonable person… His win confirms a fact. Walko was the bravest, the most constant, the most healthy.”

L’Equipe and the Tour came around to Walkowiak but was this an appreciation of his ride or a commercial need to promote the winner? Blondin, no stranger to a bottle or three of wine, was probably the last person to take the corporate line, in fact his piece praising Walkowiak criticised other aspects of the race. Later on the Tour organiser Jacques Goddet even dedicated his memoirs, L’Equipée belle, to Roger Walkowiak so much did he like this edition of the race and its winner. Other newspapers, newsreels, radio and television were less generous and Walkowiak began to lament his win, “I felt as if public opinion thought the Tour was too important for a rider like me“.

From Tour champion to tourneur

Walkowiak’s career continued as it had been before: without further crowning success. He returned to the Tour de France in 1957 only to see Jacques Anquetil emerge as a star, the darling of the public. In a race with a high attrition rate he abandoned on Stage 18 becoming one of only six “defending” champions of the Tour to quit (Froome 2014, Hinault 1980, Thévenet 1978, 1976, Bahamontes 1960, Anquetil 1958). Walko soon quit cycling too. Out of work he returned to factory where he was once an apprentice and resumed his career at the lathe, a tourneur. He later tried his hand at farming. He avoided the media for decades until an interview with L’Equipe in 1985. “They stole my Tour, they’re bastards” he said about the Parisian media who he accused of underestimating his win and the effort involved.

More recently in an interview with French TV he breaks down in tears when asked about his Tour de France win, still hurting at the accusations that he won the Tour de France thanks to one flat stage. He says he never talks about the win with his wife either, the subject is too hard to broach. A more recent interview by Bicycling’s James Startt sees Walkowiak telling the story from his side.

What if Walko had lost?

Historians and sports fans share the love of the counterfactual, the idea of events taking a different turn had someone done something different. What if Gilbert Bauvin had won? He was the leader of the French national team but hardly a great champion either. Maybe the Tour would have made him into something bigger but his palmarès prior to the Tour was only marginally superior to Walko’s thanks to a few wins and two spells in the maillot jaune. He too made the maxi breakaway that gained 31 minutes. So maybe we would have a win “Bauvin style”? That said he was still more of a media darling than the modest Walkowiak.

Conclusion

Did Walkowiak get lucky? Yes because for various reasons several star riders did not start the 1956 Tour de France. Yes because he joined a breakaway that to took 18 minutes on Stage 7. But you make your own luck. He was in the succesful breakaway for two straight days before the 18 minute move which meant he’d already gained time on rivals including those that made the maxi-break while the pre-race favourites were floundering in the cross-winds.

When the Tour went into the Alps he climbed back into the yellow jersey and was matching the best on the big climbs. His lack of style and his self-effacing modesty didn’t endear him to the media but he won a race with a record average speed.

The race had big breakaways staying away. The yellow jersey changed shoulders eight times with Walkowiak losing the lead only to win back the yellow jersey thanks to some valiant riding. If only every Tour could be as exciting.

Just finished a Beppe C0nti historical piece in Bicisport this morning and now this – MERCI!

I wonder if ‘winning a la Pereiro’ will ever become a thing? Not a dissimilar story in many respects, just with the added Landis drugs bust to spice it up

It’s never stuck but it was an odd Tour and he ended up the accidental winner, because of a giant break but also his clever riding… but above all because of Landis’s declassification as you say. Pereiro’s often seen as the guy who made one big break and got lucky but there was more to his Tour than the one lucky stage.

One could argue his best bit of luck was not getting popped along with the rest of them!!

Great story. Small correction: Wagtmans was Dutch, Adriaensens (one s in the middle) Belgian.

Thanks, got the nationalities crossed. Adriaensens seems to be spelled with two s’s in the newspapers from the time but happy to change it too.

The number of ‘s’s comes from wikipedia so there you are probably correct (unless the papers aren’t in Dutch). My antenna went up when I saw Wagtmans had changed nationality.

Great vindication of the man, INRNG. Like many (in our niche of the sporting world), I was also under the impression that winning a la Walko was equivalent to one lucky break. But the way you tell it – matching Bahamontes in the Mountains, retaking the jersey after losing it – his win seems every bit as hard fought as any other. Fascinating, then, how his name for posteriority is associated with an undeserved win.

Well mythbusted, sir!

“Fascinating, then, how his name for posterity is associated with an undeserved win.”

Except that it isn’t, not really, as the piece makes clear. It’s associated with an unexpected win. The ‘undeserved’ slant seems to me to be both more recent and more Anglophone.

If it’s a win by someone who isn’t thought to be the right sort, the right quality, that comes closer to one nuance of the word ‘undeserving’.

But it’s not quite the sense of ‘undeserving’ as in lucky or a fluke – it’s ‘undeserving’ as in upstart or a parvenu.

Walko was sandwiched between Bobet and Anquetil and has very little else on his palmares. That’s crucial, much more so than any notion of ‘one lucky break’.

I think Walkowiak feels that some of the media felt his win was undeserved and he’s still upset by this. Mainly the phrase is about a surprise or a lucky win though.

Fascinating story!

The enormous time gaps of yesteryear Tours – breakaways gaining 10 or 20 minutes, the yellow jersey winning by hours – were those due to poor communication and incomplete information?. No race radio and so on?

Or was there something about the routes and riders that is different from today’s Tour where stages are won by seconds and the yellow jersey might have a couple minutes in Paris?

Walkowiak won by 1’45” in the end, and the everyone who finished was within 4h10′, so the 50s weren’t quite as you say.

Pretty much everything was different though. Bikes were heavy, had few gears. Clothing was wool, so the riders got hot in the sun and drenched in the rain. Road quality was worse. Average stage length was longer.

Riders were from a much smaller talent pool, as inrng says, and someone aged in their 20s in 1956 had grown up through the war, not a conducive environment to producing athletes so the differences between riders would have been larger.

Very good piece. Really worth noting these days. “Poujadiste égaré dans le Bottin mondain”, could also be translated, more elaborately, “Little provincial conservative bigot, lost among the who’s who of the global, mundane élite”. Very relevant vision even in today’s France, today’s world, and the place of our old-fashioned rural sport in it.

Fine translation 🙂

Were do you find the time?

I suppose that Lemond might have felt a bit “Walkowiaked” after his first TDF win. Given he was on a French team and living in France.

Thanks, as we simmer our way toward the tour.

Not at all. The sport’s Grandfathers knew Lemond would be great and got a ride on what might have been the best team in Pro Cycling at the time.

Also remember he came in third as a helper in his first TdF. It was only a matter of when, not if, Lemond would win. That’s quite unlike Walkowiak.

But you make your own luck.

So much unsaid in that little nugget of truth.

a “petit-bourgeois lost among aristocrats”.

So, he was the underdog?

Enjoyed that one, most educational.

Very.

I did not know about this man, but have done some background reading following this article.

It seems the man is a fighter, fought all his life, and deserves huge credit.

A Tour win is still a Tour win regardless of how it’s earned. You’ve still got to ride every meter over mountains and through the valleys. There are no undeserved winners, only petty losers. Walko is a real past favorite of mine for his abilities and manner which earned him some good respect from those who rode with him.

All that said i’m never hugely into races where the GC winner doesn’t win a stage, but then none of the Top3 did. Was also a bit of an odd route no Summit Finishes in the high mountains. Imagine the outrage if that happened now!

Unrelated Fun Fact: 1956 was the first year riders could change a flat tyre and not have to repair it!

I think some of the contemporary criticism of Walko derived from the fact that he hadn’t won a stage. His win was thus seen as lacking panache, particularly at a time that had seen a series of great champions winning in the previous decade since the war. Had he won a stage – either over the Izoard, or one of the maxi-breakaways, it would have seemed much more that he had seized the initiative in order to win the race.

Tom

A good point, he’s the only Tour winner never to have won a stage of the Tour de France during his career. Some have taken stages earlier or later in their career, for example Pereiro.

Well none of the Top3 won a stage that year, so i’m not sure who “should” have won the ’56 race. 5th place Defilippis took 3 stages. 8th Place Ockers took one win. Other than that no Top10 finisher won a stage. Bit of a strange race in that aspect, but as a result it shouldn’t diminish Walkowiak’s win seeing as his rivals couldn’t win either

A great story and a classic example of the media distorting the truth. Competing in stages of 9 hours and having a win reported as “undeserved” goes to show how easy it is for those who have never ridden professionally to deride another’s efforts. How many of the “gentlemen” of the press could ride a tour stage, let alone be competitive in the whole race? Maybe it happens a little less today, though I would love to see an Etape for journalists so they could get a real insight into what’s involved in pro racing.

This story reminded me of the year that Nibali won the Tour–was it 2014? That year Froome, the previous year’s winner was knocked out early on, and so was the other major contender, Contador. With the major competition gone, Nibali was the leading candidate for the win. This didn’t mean it was a cake walk for him, but it did improve his chances for the win drastically. But clearly, Nibali is different from Walkowiak thanks to his illustrious grand tour wins and prestigious palmares.

It’s similar in the sense that a lot of people, especially in Italy, went on diminishing the meaning of that victory, but truth is that Froome wouldn’t have had a chance, in that Tour, and Contador winning options weren’t that high, either, at least at the point of the race when he had to retire (even if with Contador you never know and he had great form, that year).

Besides, there’s a difference between not starting and falling off your bike and retiring, even more so if you’re falling because of a silly mistake you end up making because of nerves – which applies more to Contador (or to Nibali 2015…) than to Froome, since the latter could blame mainly a lack of protection by the team and a certain lack of skills, but in all the cases it was far from being sheer bad luck.

Great piece, thanks. You put in the picture of the old Dunlop site and only referenced it in the body text, one of several nice touches.

Thanks. Dunlop’s factory dominates the town or rather it used to, it seems to be crumbling now but they still make high end motorbike tires there. Walkowiak rode for the Dunlop factory team as an amateur and turned pro with a team sponsored by Dunlop too.

Even crumbling it’s a lot nicer than the tumour Travelodge stuck on the lovely former Fort Dunlop here in the UK.

Lovely piece of history and beautifully told. Well done!

Interesting how so often the “Media” can decide on who is a deserving or lucky winner based on some random criteria but not on the facts of the race. It seems that a single piece of journalism can sometimes sully a great sporting feat.

Walko seemed like the perfect underdog that the French public and press have so often championed over the years. I wonder why it didn’t happen for Walko?

I couldn’t hold back my tears watching his interview with FranceTV. As you said, his modesty didn’t allow him to become a media darling. The story also serves a reminder to people (including myself) who belittled Wiggins’ 2012 win that winning a Tour is a mighty achievement in any condition.

Thank you again for this beautiful piece.

Thanks, very nice article!