Many sports are bringing in procedures to deal with concussion. For years a knock to the head has been part of the rough and tumble of sports but medicine has shown that one hit can cause brain trauma and crucially a second or repeat injuries can compound this and cause permanent brain damage.

Pro cycling’s started this process too and it’s very much a learning issue for team medics, race doctors and officials. There are guidelines and procedures which have been borrowed from other sports but they run up against cycling’s very nature of travelling across the landscape. James Knox’s disqualification from the Tour Down Under was instructive as it raised issues but I wanted to wait and take stock of the situation rather than replay one case.

For most sports there are two paths to reduce concussion and brain trauma. First is to reduce head injuries, for example in youth soccer some have adopted the practice of not heading the ball, or are trying to cap the amount of headers a player can make. In cycling helmet use helps mitigate this. The other path is to examine participants who have taken a knock to the head. In field sports like soccer or rugby this is easy with players benched while medics perform health checks to test their cognitive function. Cycling has borrowed from this with shared guidelines from ice hockey, equestrianism, soccer and rugby but it’s here where the problem comes for cycling because you can’t rest a rider for a few minutes to perform checks because the race is riding away.

In a sport where just closing a ten second gap to the peloton can be tough, let alone getting going again after a crash, a bike change, waiting to get a medic on the scene and then doing the checks which can take minutes. Sometimes a rider can be so far behind they have to be disqualified because the broom wagon’s gone by and they’ve had to reopen the road to general traffic.

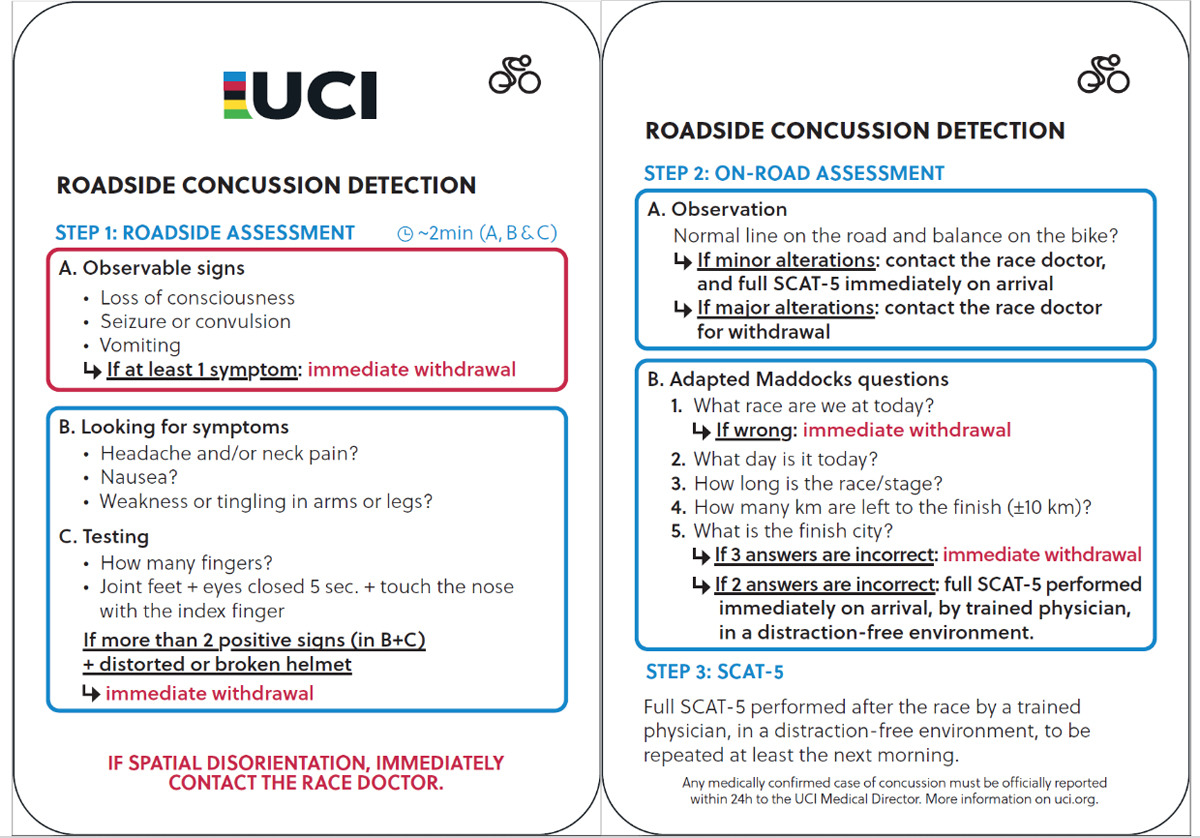

That’s the pocket-sized card for concussion checks, literally a cut-out and keep guide to have in a race vehicle. It’s important to stress this is just a guide and something done in the moment following an incident, there’s a longer checklist to go through after the race and the race doctor is usually tasked with the follow-up, they should ask after the rider involved or get team staff to monitor them.

Stopping to do a concussion assessment is the right thing to do so losing time shouldn’t be a consequent penalty. Easier said than done to correct this. First some races can run to a tight timetable, especially early on the course and a rider could find themselves out of the race by stopping for too long as police or marshals reopen the roads to traffic so even trying to pace a rider back after a check can be out of the question if there are traffic lights or roundabout priorities to respect. The concussion check has to be done at the side of the road rather than when a rider holds onto the doctor’s car and the medic’s car isn’t a specialist taxi or motor-pacing service, and while we’ve all seen how easy it looks in the Tour de France, not every race has convertible cars, nor medics and drivers who are so experienced. Remember we’re dealing with riders who might have sustained a head injury. Pacing back with the help of the medics car is not ideal. Maybe a waiting team car could be better? Yes, but still risky. Maybe a vehicle where the rider can get inside and is transported? But in the time you’ve taken to read that one you’ve probably worked out that the car couldn’t just drop the rider back in the field, they’d have to find a place to stop, get the bike off the roof and it’d be complicated, who regulates this?

Which means even if some sort of compensatory pacing or travel is allowed, the next question is how much? A footballer can sit on a bench and return to the field of play after 10 minutes. Is the rider towed back to the peloton? Not always, imagine a multi-rider crash where other riders are trying to make their way back, anyone who’s stopped for a concussion check should probably be allowed to rejoin these chasers, but not get an advantage beyond this. So it’s almost as if an extra commissaire is needed to work out who could be given some assistance back and they in turn have to know the location of riders and time gaps, much easier said than done.

One issue that doesn’t seemed to have happened yet is a rider being stopped from racing – disqualified for their own good – if they display “red flag” symptoms following a crash, only for subsequent tests to reveal there’s no trauma; take a random example where someone shows outward symptoms like slurred speech because it’s because they their tongue in the fall; or what someone looking at a rider mistakes for a convulsion is just cramp. Now a medic should be able to tell the difference but given there are few medics around, others are given the authority to exclude a rider from the race like commissaires, team staff and race officials. This extended authority to exclude a rider ought to be a good idea given the precautionary aspect but you can imagine the online outrage if a rider is ejected by someone who earnestly believes they’re doing the right thing but turns out to be wrong. Hopefully it doesn’t happen but it’s just something to be aware of, there’s a grey area when non-medics are tasked with diagnosis.

Another issue is whether riders stay in the race. The sport was founded on the myth of resilience and endurance rather than speed or skill. Riders were celebrated for overcoming adversity of the time with ideas like Nietzsche’s Übermensch and it’s a theme that persists today, the Tour de France is special because it is so gruelling. We’ve probably all seen the meme where cyclists mock footballers who dive at the slightest touch while the hardy rider hauls themselves out of a ravine. But the football dive is all about incentives, the chance of getting a free kick from the referee or removing a rival from the field of play. Now road cycling has its own incentives too as a cyclist who suffers a fall may feel compelled to get back on their bike before the gap grows, and downplaying or hiding symptoms becomes part of this. They may feel loyalty to team mates or pressure from management. One aspect here might be to normalise withdrawals so it just becomes one of those things, that riders and team managers alike know it happens to a lot of riders and it happens often.

There could be wider policies such as rider substitutions during a stage race. This is changing the nature of the sport and perhaps a step too far? After all a rider who falls and loses skin or breaks a bone doesn’t get replaced and which teams have riders spare who can travel with a race just in case.

Conclusion

Concussion checks are the right thing to do and there’s an awareness campaign to make everyone in the race convoy aware of the likely symptoms. They’re handy to know for a group ride too.

The big issue is the addressing the time cost of stopping riders beside the road. Just pacing a rider back isn’t as easy as it sounds, hanging behind a car at 60km/h or more is risky at the best of times, more so if a rider might still have brain injuries. Finding reliable ways to mitigate the penalty is hard, a solution that works in the Tour de France has to work in the Tour du Poitou-Charentes as well. There are practical challenges like working out how to get a rider back to the race and also cultural ones like overcoming the almost instinctive instinct to jump back on the bike.

The thing to cheer though is that at least riders are being checked, the real problem was when nobody cared or noticed. It’s not an intractable problem but solutions, if the sport can find them, are going to be clumsy and imprecise.

- some of the images are of riders who’ve crashed but without concussion

If WT helmets had accelerometers fitted as standard, could this help remove the guesswork?

You can have the head movement/rotation vector change plus showing or not of various red light symptoms. Pit these against concussion diagnosis, you get a training set data for AI. With enough training data, an AI can get this relatively accurately. At least this might provide some support when a non-medical personal would need to make a decision.

That said, AI might get as good or better at doing a diagnose directly from video feed.

One problem with AI diagnosing from a crash is that different people react differently to a head knock due to genetics. A family member’s experience (albeit in rugby) was that they would suffer badly, long-term brain fog and almost MS/CF-like symptoms for a few weeks/months; whereas others would recieve similar looking knocks and recover much more quickly.

Riders can be out of sight when they land off the side of the road. They might make a soft or hard landing. Video is even less reliable than the finger-count test.

Accelerometers are cheap and reliable. An ANT or pluggable device would weigh under 20g (they put trackers on insects these days..). You could even have one that signals to the medic car and race control, as well as the rider’s head set to say it’s race over for them.

Obviously the parameters would have to be set, but there is already a lot of data from other sports and medical studies. It wouldn’t take long and could be monitored over time to perfect protocols and equipment.

I have some experience with concussions from a crash in 2010 that had effects for about two years after. I have also discussed the matter with a physician who runs an internationally recognized concussion clinic and consulted to me after my crash. A concussion is a form of brain damage. You only get one head and repeated damage or one severe event can have lifetime effects. In my opinion both riders and officials should err on the side of caution.

It’s easier to make decisions at one day than stage races. At one day races, any sign that a rider has hit their head on some sort of impact should lead to exclusion. Someone who’s suffered head trauma in a one day event is unlikely to be a factor as winner or helper so stopping is easier. The UCI rules would only be used if the impact isn’t obvious but the rider shows some effects of head trauma.

Stage races are a tougher call. Racing is the livelihood for these people. They’ll want to continue and their teams will want them for support or stage wins on later days.

Whether one day or stage, the exclusion events in A on the roadside assessment are pretty obvious. The B and C items on the roadside assessment probably don’t take much more time than it will take to get the rider’s bike ready. The question becomes who asks the questions or observes the rider. Ideally, the race doctor. If the race doctor isn’t present, a commissaire. No appeal to whatever decision is made on site. If doctors or commissaires aren’t available and team management makes the immediate call, a race doctor should be summoned to conduct the on road assessment. Again, no appeal to the doctor’s decision. No more than normal pacing back to groups ahead. If the team feels the rider is so valuable that they are prepared to allocate one of their team cars to follow the rider ahead of the broom wagon, they may do so but can’t pace the rider indefinitely.

If the rider is excluded through the roadside or on road assessment, there is no replacement and no second chance. It’s just a racing incident like a crash in which a rider breaks their leg.

Agree 200% with all of this. Having had several concussions over the years of my long ago youth, the repercussions if not properly dealt with can be lifelong.

Probably the closest we can come with stage races is to keep the rider in the car till the end of the stage then allow them to rejoin the next day with no loss of time. This would also allow for a longer observation period. One day races are more difficult but the rider may have much less investment. Being pulled from a race at hour 3 is quite different from being pulled on day 10.

Always though, rider health must come first…

Tricky, but for a stage race, I’d be tempted to get the rider to sit out the stage, allow a restart the next day, but be excluded from GC. So, a top rider in the TDF could pursue stage victories in subsequent stages, but couldn’t win the overall as they clearly haven’t done the whole race. If they need to sit out more than one stage, they’re excluded. The independent doctor would need to be the only party that verifies the “exclusion”.

It’s difficult as it could be the right thing to do for health but it goes against the sporting aspect/tradition of the race. If a rider sits out a stage but pulls for their leader the next, do they have an advantage? Probably but maybe it’s the price to pay to this?

We already have a range of rules that distort the absolute nature of a bike race such as the 3km rule that corrects for crashes, plus the “unwritten rules” about inopportune crashes or mechanicals etc. I suspect the sport will slowly work its way through to a solution.

I feel it will end up being necessary to have something like the 3km rule for riders who are stopped for examination but subsequently approved to ride. So they end up getting the same time as the group they were in at the time of the incident that gave rise to the need for a check. Otherwise, riders will be reluctant to give up the time for the examination if they see the race riding away from them.

Clearly some wrinkles to work out on, say, mountain stages where a ‘group’ would finish at multiple different times, but not impossible.

A data-informed approach could be handy for deriving the time to be awarded when a rider is delayed by waiting for an assessment but subsequently rides to the finish.

Look at their previous performances on similar stages at 2.1 or higher level, then use that to award a time as good as the median stage time of the rest of the group they were with (if the data shows they perform well in that type of stage) or potentially as bad as the worst stage time of the group (if the data says they were probably going to come in way behind).

For a rider who is medically disqualified but allowed to rejoin the next day after further examinations, I don’t see any option being fair other than exclusion from the GC. When they have saved a whole lot of kilometres there may even be a case for exclusion from participating in the final of the next stage (i.e. no pulling on the front in the last 20km or on the final categorised climb).

For me, we need to minimise (as much as possible) the perception that waiting to be assessed properly is punitive. This is the biggest issue in stage races. Trying to work out ways to ‘transport’ riders back into the race are full of problems (and maybe susceptible to be games). So maybe a fair balance for stage races, is that a rider requiring a full assessment is allowed to sit out the rest of the stage as a precaution, but can rejoin the next day, however they can, but no longer count in classifications. So could play a team role, but that’s it. A crash requiring a full assessment is likely to be substantial, so any nudge towards pulling out might not be bad in the long run, but it would allow some encouragement to engage in the process. Let’s face it, a large majority of the peloton in a stage race are not contesting GC- so for many, being able to continue, be a domestique (maybe be allowed to claim stage wins) would be business as usual.

It is a tricky solution to find, but one that needs to be attempted. Normalising protecting long-term health should be a priority. There’s also a need to think about contract security in this as well re recovery from concussion (and all health problems to be honest).

From my one experience of being knocked out when riding the only observation i can make is that the rider cannot make the decision if they have had a knock to the head. On my crash i had shattered some bones and couldn’t stand up on my own yet i fully expected to get back on the bike and ride (this was not even a race). You may be concussed but to yourself you feel normal.

I like the idea of a rider removed due to a head knock is given the bunch time if he is later found to have been okay.

If you can find a video on youtube of chris horner after he was concussed during a tdf stage it is very scary.

He crashed with 25 km to go and when he gets to the finish on his own he cannot remember he was in a crash. He’s not sure why he’s on his own. After he’s seen the medical staff he keeps asking if he finished as he basically keeps forgetting everything he has been told.

A very enlightening video on cycling concussion.

I remember that with Horner.

Also check video of Toms Skuijins at Tour de Cali.

It’s pitiful, he can’t even get on his bike at first.

In both of those cases you would know immediately that they were impaired.

The only New Year’s resolution I ever kept was when I said I’d always wear my crash hat.

I’ve got a stack of broken helmets to prove that was the right decision.

Horner’s case is interesting as he’s in real distress yet at the same time almost instinctively knows he’s got to get on his bike and aim for the finish line, it’s confronting this impulse that can be hard. There can be crashes that nobody sees or ones where so many riders fall that some get back up as part of the crowd and get going without time to spot that they’ve got problems. There have been cases of this happening where the only clue was that the rider looked alright, got back on their bike… and started riding the opposite way, dodging vehicles in the convoy until they were stopped.

I had a crash last summer that knocked me out for minutes. When I came round, my first thought was why has the chains come off? The second was better put it back on so I can continue riding. The paramedics who attended couldn’t understand this. I eventually spent a long time in the emergency department. The rider really isn’t best placed to decide whether to ride!

“One aspect here might be to normalise withdrawals so it just becomes one of those things, that riders and team managers alike know it happens to a lot of riders and it happens often.”

Yes. There is no foolproof way to diagnose a concussion immediately after an impact, and mild concussions are extremely difficult to diagnose even with a neurologist present. We still don’t know how much of a hit can lead to long-term damage, and it’s not even clear cut exactly when someone has recovered enough from a concussion that they can handle minor head trauma again. The attitude needs to be that NO concussed riders stay in a race, even if that means having a threshold so low that a significant portion of those riders forced out of the race turn out to not have definite concussions.

A crucial aspect is to decrease the number of crashes, especially at high speed. That should be the top priority. Which would require to shape races in a way that riders don’t have to fight for scarce space at the front of a big peloton. Courses encouraging sprint train tactics should certainly be ruled out but most importantly: safety measure number 1 is to reduce drastically the number of participants at all kinds of races. Yes, I know, it would surely mean less jobs for pro cyclists, but we’re only concerned with health and safety, aren’t we?

Have you ever seen a track race? Compared to a 170 riders road race there are only a few of them, a pretty well known course, and still they crash.

Maybe curling is more for the over cautious and frightened.

This is one area where UCI could do a lot of good at very little cost by commissioning research using the pro peloton as subjects in a wide study of real world head impacts where it’s possible to record full data of each impact. Minimal individual follow up with simple cognitive and conductive testing ( which you’d hope team doctors would be doing anyway ) could lead to a rich set of concussion data and a refined approach to in-race actions when a rider has gone down.

And to make it fair, riders with a red light on possible concussion should be allowed back into a race somehow. – only until such time as the studies work out what counts as a race-ending head injury.

A small point of order…

“A footballer can sit on a bench and return to the field of play after 10 minutes.” Yes, but only if his team plays a man (or woman) short in the meantime, which is disadvantageous. Several leading leagues have urged IFAB – the organisation that makes the rules – to allow temporary substitutions in order that a proper assessment can take place, but so far the only permitted option is permanent replacement.

Rugby is ahead, with head injury assessments built into the game now, although far behind in terms of the risk to players, cf the ongoing legal cases and distressing stories that accompany them.

On a more general theme, the ideas suggested here are all worth exploring.

Aside from motorsport which has a large industry backing it and an active pro-safety culture, the leading sport with regards to concussion is undoubtedly cricket.

In the last decade and a half they have reduced the exposure to head high bowling, completely replaced the old helmet standards, introduced concussion substitutes (going against a fundamental rule that was older than road cycling – the same 11 players complete the whole match) and normalised their use such that nobody blinked when a substitute was called on in the World Cup Final a couple of years back.

The likelihood of being concussed during a typical cricket match must be miniscule. All the more credit to the authorities for taking action rather than brushing aside concerns. Maybe one high-profile tragedy made all the difference?

Contact and high-speed sports (cycling, skiing) have a much higher risk and by their nature are harder to change both rules and behaviour.

> The likelihood of being concussed during a typical cricket match must be miniscule.

It’s actually quite high, which is why players batting or fielding close to the batter wear helmets.

Depending on the format, fast bowlers may bowl either 1 or 2 ‘bouncers’ which reach the batter at head height in every six ball Over. There’s also the risk of a player incorrectly reading a ball bowled at below shoulder height and ducking into it.

The substitution in a World Cup Final that I referred to was a player who mis-hit a fairly slow ball (i.e. 70-80 km/h) from a spin bowler (not a head high bouncer from a fast bowler) such that the ball deflected off the edge of her bat and straight at her face.

Players have also been substituted for non-batting incidents, including one player last summer who was attempting to catch a ball low to the ground when his head hit the ground.

> Maybe one high-profile tragedy made all the difference?

The death of Phil Hughes in 2014 made all the difference to the helmet standards (he was hit below the helmet on the side of the head) but it was still more than four years after that before concussion substitutes were introduced to international matches. At the time of his death they were already in place at lower levels in Australia.

Great topic (I crashed and suffered a concussion 18 months ago now, I’m still not 100%, but consider myself lucky).

I think the solution might take some trial and error… including the doctors need to keep an eye out in race for those who crashed mid stage, determine if symptoms present on a delay OR if the rider was hiding them.

Will take those concussion guidelines to share with my club, ideal for cyclists to know when out on a ride together 👍