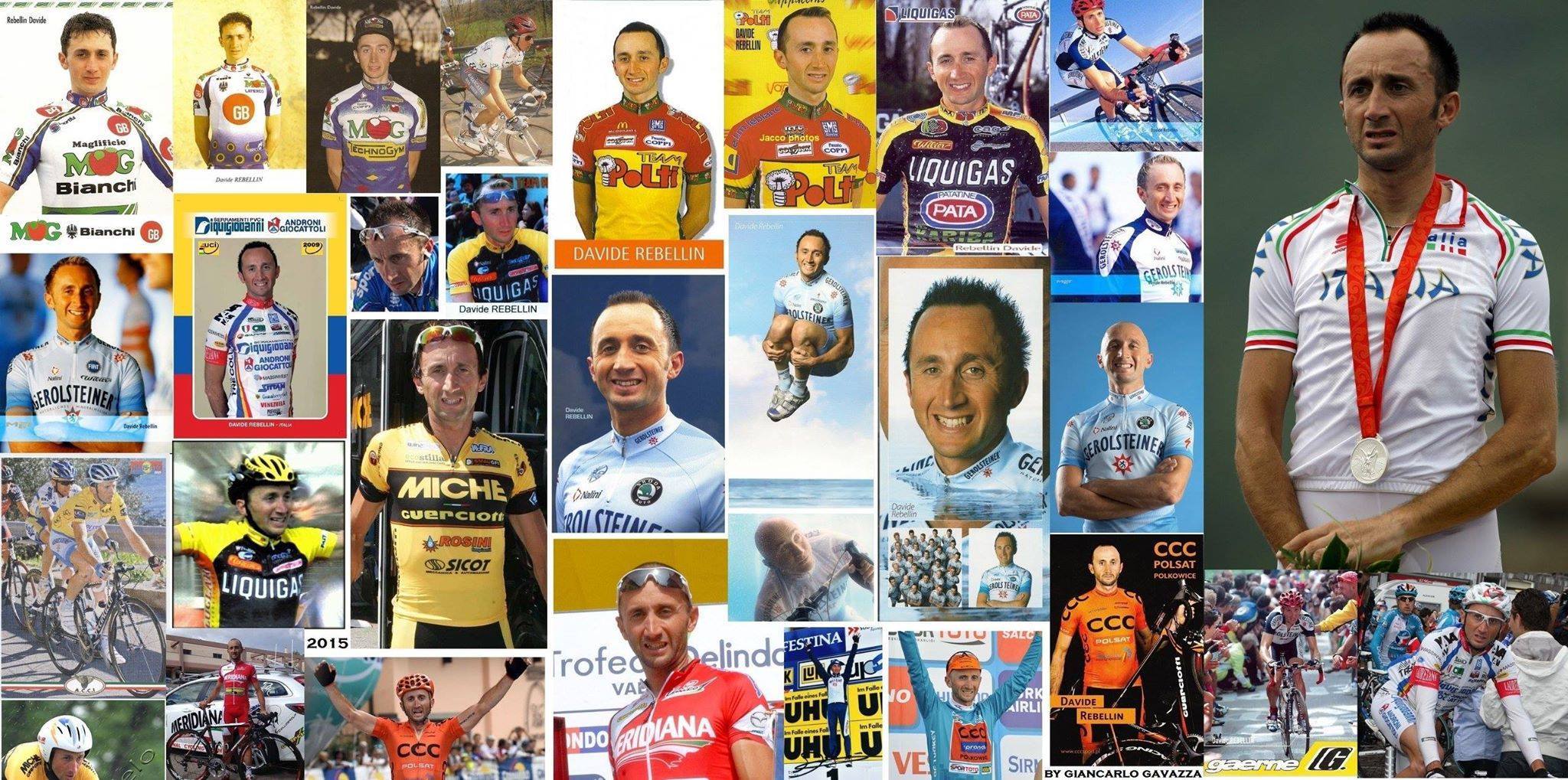

Davide Rebellin died on Wednesday, days after retiring as a professional cyclist at the age of 51. His career was so long it spanned the steel, aluminium and carbon ages of bikes, during which time he won over sixty races. He claimed he must have ridden a million kilometres and once said “the bike taught me how to live“, with both highs and lows along the way.

Born in 1971 in San Bonifacio in the Veneto region in north-east Italy, he grew up in Lonigo, the next town across. In school he’d meet his first wife Selina Martinello and get in cycling early thanks to the influence of classmates at school and an uncle in a local cycling club. His father Gedeone became his first sponsor, backing the Rebellin Market team, sporting the name of the family food shop. There was talk of becoming a priest but his future was on the bike.

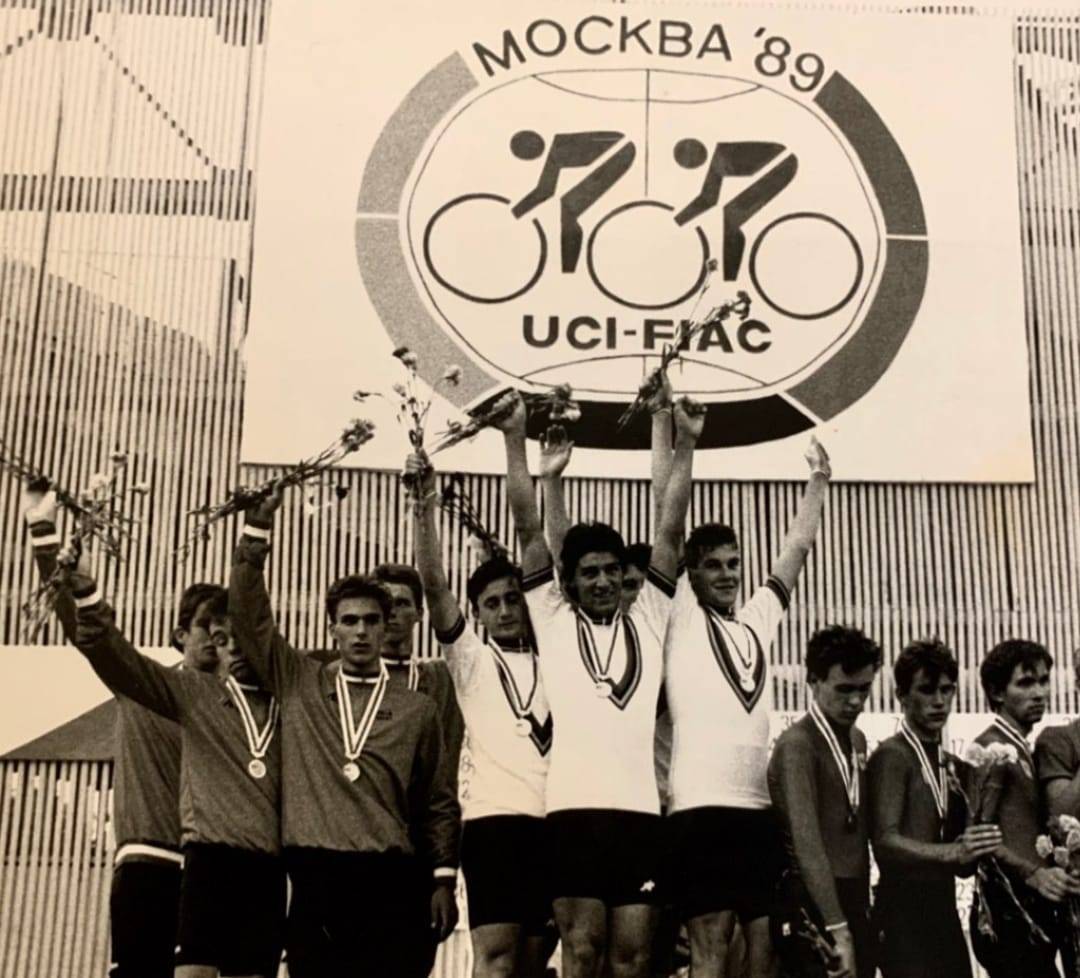

A decade later he was a world champion in the junior team time trial event held in Moscow. More wins followed and he turned pro in August 1992 after the amateur Barcelona Olympics. He signed for MG-Technogym, a team that rode on lugged steel Bianchi bikes managed by the “Iron Sergeant” Giancarlo Ferretti. Rebellin’s shyness and Ferretti’s authoritarian style meant he struggled. A quiet man, his team mates would nickname him chierichetto, “choirboy”, on account of his faith and timidity. He wasn’t shy on the bike though and enjoyed a decent first season, ending the year with a ninth place in the Tour of Lombardy aged 21, outsprinting Laurent Madouas. 27 years later in the GP La Marseillaise Rebellin would finish one place ahead of Madouas’s son Valentin.

He moved to the Polti team for 1996. He told Italian journalist Marco Pastonesi that his most beautiful day came in 1996 during the Giro d’Italia when he won atop Monte Sirino, taking the stage and leader’s jersey in a race where he’d eventually finish sixth overall after a spell in pink. That would be his peak in a grand tour, he was better suited to one day races and the following year, while riding for the nascent FDJ team, took two World Cup races, the Clasica San Sebastian and the GP Suisse in Zurich.

He was best in races with with short, steep climbs. No more so than the Flèche Wallonne, a race he’d win three times and in his first win in 2004 with the Gerolsteiner team he took the Ardennes “grand slam”, winning the Amstel Gold Race on one weekend, the Flèche on the Wednesday and Liège-Bastogne-Liège the weekend after, a feat nobody had done before, and only Philippe Gilbert and Anna van der Breggen have accomplished since. That thought wasn’t sufficient to get him a ride at the Athens Olympic. Frustrated, he applied for Argentine citizenship and a licence but the paperwork could not be completed in time, outwardly it looked farcical but presumably he just wanted to ride.

Marco Bonnarigo wrote in Il Corriere, a newspaper, that Rebellin’s chierichetto nickname also came from a “terror” of approaching doping, but that after ten years as a pro, “so goes the legend” writes Bonnarigo, he “gave into temptation” which would put this switch this soon after the turn of the century, and if the legend’s true then his Monte Sirino ride is even better. While many swam through the anti-doping nets, Rebellin got entangled in 2008. This time he was selected for the 2008 Olympics, for Italy. 16 years after he’d raced Barcelona, and aged 37, he’d ride to a silver medal in Beijing but this didn’t last. With anti-doping samples being retested for CERA, a new class of the blood-boosting medicine, Rebellin was among those to test positive; his Gerolsteiner team mate Stefan Schumacher was done for CERA too. After an appeal claiming the testing methods were not valid he lost his medal and got a two year ban, the standard tariff of the time, while a tax investigation as to whether he was really resident in Monaco or actually living in Italy hung over him for years, before he was acquitted.

The ban served, he resumed his career and found winning ways but spent two years with third tier Continental teams before spending four seasons with the Polish CCC team. While others were racing the Giro in May, he was at the Azerbaijan Tour; not for him the Tour de France in July but Romania and the Sibiu Tour. Why keep racing into his forties and on the margins of the international calendar? He’d reply how important cycling was for him, for example telling Marco Pastonesi:

The bicycle… … is my life. I feel like I’ve been pedalling since I was born. I grew up on the bike, I saw myself in it, I suffered, but also rejoiced, the bike taught me how to live

Sometimes it seemed as if cycling was the only thing Rebellin really knew. He featured in Il Ultimo Chilometro, a short film from 2012 and the moment he was off the bike or not talking about cycling he seemed lost, even cutting a forlorn figure just queuing for a sandwich in town. Like a bicycle itself, he had to keep pedalling in order not to fall down. He said his second marriage to Françoise “Fanfan” Antonini helped him develop as a person. Speaking to Bidon magazine’s Leonardo Piccone, he opened up:

When I met Françoise I was half a man. She opened her heart to me and pushed me to believe more in myself. I thought I was only good for pedalling, but her love transformed me and allowed me to discover the man I am, and that I didn’t even know. She taught me the importance of following happiness and focusing on beautiful things

While he was never keen on social media, he took to posting images of his organic, vegetarian diet, and also wildlife, such as encounters with a fox during a training ride. He’d stop from time to time just to take in the scenery.

Rebellin became a Peter Pan character, albeit with the signs of ageing, and ech year he became more of an amateur in the original sense, doing his sport for the love of it. But also because he did not feel like doing much else. He knew how to keep riding and racing, typically training alone and being particular with his diet. Film makers La Bordure made the gentle “Il Vecchio Saggio” (the Old Sage) documentary showed Rebellin where he’d bring his own food to races, mixing his own breakfast.

In the same film journalist Philippe Brunel describes Rebellin as “a passing dream” where people could project their thoughts onto him, saying some will adore him for the image he gave as someone raging against the dying of the light; while others might see a pathetic figure seemingly stuck on two wheels. While Rebellin must have been sensitive to what others said and thought, he was just doing what he wanted and that was riding his bike and pinning on a number. In the interview with Bidon he said that he’d been riding an average of 35,000 kilometres a year since turning professional and estimated that by adding his amateur and childhood days he must have ridden a million kilometres.

33 years after winning the worlds in Moscow, Rebellin compete at the 2022 gravel world championships. He officially retired with 30th place in his final UCI race, the Veneto Classic, and on his own training roads. He was not going to stop riding though, he had plans for gravel racing and training camps. Last weekend he rode Matteo Trentin’s BeKing criterium in Monaco. On Wednesday he went out for a ride on the roads of the Veneto where he grew up. On his way back, at a roundabout less than ten kilometres from his mother’s house, he was hit by a truck and killed. Cycling seemed to give everything to Rebellin until a truck driver took it all away in an instant.

(📷 : unmarked images via Davide Rebellin Facebook)

How sad. Rest in peace Davide.

“He had plans for grave racing.”

Interesting typo

RIP Rebellin

Gravel of course and fixed.

“winning Liège-Bastogne-Liège on one weekend, the Flèche on the Wednesday and the Amstel Gold Race the weekend, a feat nobody had done before…”

Amstel Gold Race the weekend “prior?”

Your right. The Amstel and Liège swapped places on the calendar and I thought it was more recent but it was in 2003.

Thank you! That is the obituary I had hoped for, and I knew where I would find it. 🙏

What a horror! And yes, as road cyclists we’re way more often close to the edge than we want to believe.

STS, said what I was thinking too on both accounts.

Thanks for the nice obit – tragic end to a life on two wheels.

Thank you for this obit, I don’t think Rebellin was tragic at all. His final years of racing and “post-racing” plans (of more racing) just shows this was a man who loved to ride a bike, and shares this same passion that we all have.

He was a reflection of the cycling generation he excelled in, from the ups and the downs, but was able to resuscitate his career and prove he just loved to race after serving his ban.

I’m praying that we can all learn from his very sad finale, please ride safe and do everything to enjoy the roads and avoid traffic… it’s so dangerous and unfortunately we will lose in any battle, regardless who is at fault.

Very well said.

A tragedy for Rebellin’s family and a reminder of how fragile and exposed we are on a bike. I have hardly done 20% of his claimed 1 million kms, but have had many a near squeak doing them, and most not my fault. Take care one and all.

Absolutely tragic event. Scarponi, and now Rebellin. Unbelievable how two of Italy’s stars could meet such a sad ending. Speechless.

Absolutely tragic event. Scarponi, and now Rebellin. Unbelievable how two of Italy’s stars could meet such a sad ending. Speechless.

Also ercole baldini, 1958giro

winner and World champion, World hour record holder, died yesterday (1/12) aged 89.

It really seems that only time and age brought him happiness… I remember the triplé in the Ardennaises, it was awful to watch, but his longlasting swansong showed that obstinacy, at the end, can convert into grace.

Tragic and senseless. CN notes two newspapers reporting that the driver has been found and that he has a hit-and-run and a DUI on his record. Be careful out there.

I stopped following the sport in the 90s (July ’96, to be precise) and, while I looked in a few times since then, I didn’t start following it again until a few years ago. I remember Rebellin getting started, getting busted, wrote him off, so when I saw his name again a couple years ago I figured it had to be Davide Jr. What a shock to find that it was the same Davide that started 3 decades earlier. I only remembered him as yet another doper from the Dark Ages of cycling. So thank you Inrng for such a wonderful obit that presents him in a more complete light, with its full measure of grace, as Cascarinho put so well. It is, though, inexpressibly sad that the obit had to come so soon.

after many years of jokes about how he’d be racing until he died, it is absolutely horrible that it came to pass like this. Imperfect as he was, cycling thrives on stories like his as much as it does the young superstars. A big loss, in the worst way

What a cool guy.

Thanks for this. I think I’ve been following the sport since about the time he turned pro, I can remember getting home from school and seeing him battling with Tonkov in the 1996 Giro. Sad to think how his generation have ended up with Casartelli, Pantani, now Rebellin.

Thoughts with his family now.

And thanks for this forum (the blog and forum) where we can reflect on this awful accident without the conversation degrading into the abyss.

As I hit 40 and 99% recovered from a concussion 14 months ago (riding accident, car turned right in front of me, etc) this has hit me in a big way. Cyclists are so exposed. We need to be very careful about which roads we workout on.

Please be safe everyone. Make sure your families have you for a long time. My wife was beside herself the night of my accident (I was in hospital)… and Davide’s friends and family… Ooof… it is very sad.

Maybe someone can explain how the driver can’t be arrested in Germany, that it’s not a crime in that country? Hit and run not criminal in Germany? That doesn’t sound right.

If it doesn’t sound right, it usually isn’t. “Fahrerflucht” is, of course, a crime in Germany, too. “Omicidio stradale” is specific offence for vehicular homicide in Italy, but since there is no such offence in the German criminal code the driver must be charged with an appropriate offense.

The fact that he isn’t arrested is neither here or there, he will be prosecuted in court in Italy in proper time and manner.

PS I’ve understood that the semitrailer truck was exiting a roundabout when it ran over Rebellin. A heavy vehicle like that is a dangerous thing when it makes a right turn, i cannot imagine that Rebellin wouldn’t have recognized it as such or that he wouldn’t have ridden in the middle of the lane in the roundabout and the accident is therefore as much a mystery to me as it is sad and tragic.

Thanks for the explanation

Just to add that reports in Italy say a European arrest warrant is being prepared and the suspect will likely be extradited to Italy soon.

The driver reportedly made a strange and sudden change of direction to enter a roadside diner. Nothing sure yet but the bike was apparently thrown tens of metres away, which would suggest something slightly different from the accident which we of course would imagine as standard reading about truck plus cyclist plus roundabout; and which, indeed, would be quite unexpected in the case of a million-kms seasoned pro rider. But we just don’t know much yet,

After the Gravel Worlds, I thought it would be nice to see Davide to come across to the States to take in some of the racing and vibe a la Laurens ten Dam. RIP.

Something which gets often a bit overlooked is really how high a level Rebelling brought on well into his 40s. Not just about hanging around, even if you decide to leave out that Flèche won for Savio when he was already nearly 38. Riding for a weak team isn’t easy, not much support and often it’s also hard to rise your bar against a significant benchmark when your team only gets a poor to mediocre calendar, and yet the man won Tre Valli and Emilia when he was already 40 or over, two HC races which could easily be WT, especially Emilia which he won at 43. And he was already 44 when he got his last top level victory, a Classic like Agostoni, over Nibali, Bonifazio, Nizzolo and Colbrelli. To me, even other later results which surely catch less the eye are also really impressive, like top tenning in the Nats or Volta a Portugal, or being 14th at Brabantse Pijl or 21st at Sanremo, when he was closer to his 50s than to his 40s, like 47 or 48 year old, which is simply brutal from the mere POV of fitness and fast reaction times (good late results at Amstel, too). It wasn’t just an old champ striking the target in minor races, which he also did, it was being able to keep himself incredibly close to the very top level of pro sport, albeit surely in specific occasions which he prepared well. At an age which was well beyond the term of comparison of other exceptional athletes like Valverde.

Now. I’ll try to add something which is probably out of place, yet I feel that this is precisely the time when it must be stated, however complicated – and I’ll probably fail to make sense of it. Cycling as a sport is a part of cycling as a whole. Not many sports share this peculiar nature to the point cycling actually does. We can ride safe, and have to of course. I hate traffic and when riding for pleasure I choose the roads with the least motor vehicles. But. Not every cyclist is having a workout, not everybody can choose his or her roads. Even when riding as a sport, part of it can be sheer mobility, by the way. As in Rebellin and Scarponi’s case. Because they often commute to their “riding office”… by bike. Which is great, by the way. It shows how interconnected cycling as a sport and a way of transport still are. A relation deep rooted in history, but no need to delve into it now. That’s why I feel that reacting as in “let’s ride safe” is not enough. Especially in situations like Italy’s where cycling deaths are well above any theoretical minimum and most meaningful comparative standards (but, hey, even in France they probably need to tackle the whole thing again because figures are on the rise again). It’s not about utopies or target-zero, it’s about a whole system which is quite much ill-working – as I wrote before, this is the tip of the iceberg, and it’s a huge tip for a huge iceberg. The same day Rebellin was killed, a SUV killed a 16 year old and ran also leaving a 17 year old badly injured on the road. The driver “voluntarily” went to police some hours later… this goes so much beyond training and the tragic loss of two top athletes in just 5 years. I’d dare to say that it implies so much for our societies considered as a whole, especially in this time and age, from ecology to inequality. And that’s why I believe that we should perhaps listen to the call which comes with these tragic events. It’s calling us because we know to different degrees what cycling is, what cycling means, even the ones of us who don’t ride a bike. Ride safe, if you ride, for sure, but please consider standing up (not just on your pedals), sharing, associating, lobbying, in short, acting. Spend some precious time and energy in your social contexts, be it the material ones or the internet (not really as much worthy in most cases, but it’s still something, and you also can do both). Right now I don’t feel like tackling the various issues related to the “safety trap” in the case of cyclists on open roads, even less so to write about the subtle forms of victim blaming we tend to fall into (for well-studied psychological reasons, too, like unconsciously hoping we have some sort of control when we deem ourselves as responsible of the damage we suffer or might suffer)… but let’s just say that, for example, all the high-viz stuff by day isn’t much useful when drivers don’t watch, or don’t see, or don’t take into account, or don’t care. Marginal gains, surely good for anybody who feels like it, and they may well save a single life which is priceless (notably so if it’s your very own!), and still all of it barely relevant in the greater picture. Not as effective as one could believe, and sometimes it may even prevent more serious interventions on the matter. However… this really isn’t the point and I’ve written too much indeed. Let me just add that, well, we need no more martyrs, no doubt, we had so many and to so little use, yet if any day you feel especially daring and crazy and decide to face the motorised traffic, well, at least you can think that you’re fighting the good fight and helping a safety in numbers of sort.

Well said, I understand, this is a very complicated topic. Feel powerless on many levels. My cities (in Canada) are car-centric, but we have more bike lanes than ever now. However, these are often beside parked cars and with many side-roads intersecting them – so you still need to keep your head up and slow down when riding them (I was in one of these lanes at a training speed when a driver made a quick left turn in front of me – not realising i was travelling at 35+).

Be safe everyone. Save the training pace for the safest roads.

Today in my good ol’ home province back in Italy a 18 year-old was run over by a car when she was riding her bike to school on a “protected” crossing of the bicycle path she had taken. Luckily, she survived – had to be helicoptered in hospital.

In Italy cycle lanes are supposedly *mandatory* for cyclists to use, if available, but most expert riders actually avoid them (I mean, the cycle ways which aren’t fully separated from motorised traffic, given that, if they really are, they’re pretty much appreciated, of course) because they’re simply too dangerous, partly because of poor maintenance but mainly because of terrible, terrible design, so they end up being even more dangerous than riding your own way through also dangerous roads.

The law isn’t normally enforced (we had a conversation with Larry on the subject), but I guess that if you have an accident and the insurance company can find an excuse not to pay what’s due… well… here they have a big one.

Gabriele,

like you I’ve thought about this matter A LOT. Forty years and roughly half a million kilometer of riding kind of urge you to do that if it’s only to process all the shit you experience out there.

I don’t want to elaborate here and now as it’s not the right place and I know this would become a very long text.

So I’ll just jump to the conclusion I’ve come to. If we really want to improve the situation we need a “system” like in the Netherlands. Their drivers don’t like cyclists more than drivers elsewhere in the world. It’s quite the contrary according to my experience. Car drivers from the Netherlands who are not also cyclists actually often outright hate cyclists (like the majorities in many societies do). And they’ll let you feel that when they think that you on your bike are doing something which is against the law. Like riding on the road when there is a cycleway running next to the road. That is definitely not advisable, especially in the Netherlands. They even behave towards cyclists like the very worst of the domestic motorists when they are not driving in the Netherlands but in Germany, France or Italy. I’ve experienced that many, many times while being strikingly conspicuous on my road bike with bright clothing and day-time running flashing lights.

The big difference is: If as a car driver in the Netherlands you have an accident with a cyclist you’re in SERIOUS trouble. Things like “I didn’t see the cyclist” won’t work there. You have to prove – which is next to impossible – that you did everything right and could not avoid hitting the cyclist. Otherwise the penalty you’re facing will be rigorous.

It’s often said that threats of rigorous punishment don’t work to deter crimes. That might be true for many situations. In the Netherlands when it comes to motorized traffic and cyclists it works.

Everything else won’t work as the case study of the behavior of motorists from the Netherlands driving outside of their home country clearly shows. They drive like wolves in sheep’s clothing at home not because they’re inherently considerate or respectful. But because they fear the rigorous punishment which is very hard to avoid when you are involved in an accident with a cyclist.

I agree with much of what has been said above.

Italy, however, is impressive also in terms of people’s attitude towards the problem. On the Cicloweb forum, which I’ve often quoted as a well-informed source, several contributors resisted the idea that changing at least a couple of basic norms as it happened, say, in Spain might have an effect of sort, and one commenter even went as far as writing that he remembered something along the lines of Spain having the most cycling deaths in relation to population. To defend such an idea he himself posted this RTVE piece:

https://www.rtve.es/noticias/20220828/atropellos-ciclistas-sabados-medio-dia/2398627.shtml

I guess the guy didn’t notice that the 345 reported cycling deaths because of accidents with cars were calculated over a 5 years span (2016-2020).

Let’s check Italy’s figures over the same years:

2016 = 275 / 2017 = 254 / 2018 = 219 / 2019 = 253 / 2020 = 169

Isn’t it a total of 1.170? A little over *three times* the victims in Spain (I’ll later give some figures adjusted to population)?

What’s shocking is that this person, a long-time and quite expert cycling fan simply had no idea about the magnitude of the phenomenon in Italy. Despite Scarponi’s death, several recurring press reports and so on. It’s also quite much interesting to observe, in RTVE’s article, that Spain’s situation hasn’t always been the same as today through the years. It’s also worth noting that in Spain cycling among the general population has been growing steadily for the last 15 years at the very least (as confirmed by different sets of data, like polls, bike sales, public bike-sharing systems and so on). Italy had a boom from 2020 on, but before that the situation was rather stable.

As a term of comparison, France sadly had over 200 cycling deaths in 2021 (227), but it was the first time in over two decades. The 2019 (187) and 2020 (178) figures already showed a worrying trend, especially if we consider that France usually averaged some 150 cycling victims per year (e.g., a total of 757 in the five years from 2010 to 2014).

If we adjust numbers to general population (far from a perfect reference, but in recent years the three countries share a broad similarity in bicycle use), we can say that France *used to* have some 57% cycling victims when compared to Italy, or if you prefer that Italy had +75% cycling victims if compared to France, while Spain, in the very same years as Italy, had 37% of Italy’s victims (or rather in Italy some +170% cyclists have been killed by cars when compared to Spain).

That said, it’s true that heavy punishment doesn’t deter crime, but consistent and systematic prosecution does. And OTOH impunity quite surely fosters crime, too.

In my two countries, a good half of cyclists killed in collisions with a motor vehicle are old-aged people who in the vast majority of cases had neglected their obligation to give way. Fortunately most common accidents involve a car that turns right in front of a cyclist or crosses a cycle way without stopping and looking doesn’t result in deaths.

That said, every accident that could have avoided is one accident too many – and every starting road cyclist learns quite fast that all too often the only thing that can prevent an accident is being wise and being alert and, first and foremost, slowing down and giving way where you shouldn’t have to.

I’ve ridden in a thousand-strong demo after a notorious case when a driver intentionally hit a cyclist who in the driver’s opinion rode where it wasn’t allowed. I’m a member in a cyclist organisation that pushes for, among other things, the 1.5 m rule to be adopted here, too. (I disagree vehemently with its support for the use of salt to fight winter slipperiness, but that is peanuts in the big picture.) It’s not much, but I, too, have felt and I continue to believe that doing something is better than doing nothing.

I’m glad to be able to say that I generally feel safe on the roads. There are roads I like to avoid an roads that I won’t venture on during rush hours, but the only reason I need to fear is because fear keeps you alert – and that kind of fear doesn’t feel any different to the fear I feel when I ride a (for me) technical gravel road or single path descent.

Yet, between Scarponi and Rebellin two road cyclists whom I had done group rides with have been killed by drivers who blatantly broke the traffic lawa or, probably more likely, just didn’t bother to look where they should have looked. In both cases the cyclist was riding downhill in a separate cycle way that – due to idiotic design – ran on the left side of the road and the driver turned right because they had a green light that was simultanous – again due to idiotic design – with the green light in the cycle way.

Thus, when Rebellin is killed in Italy it feels just like when a cycing buddy of mine is killed or when someone’s grandpa on his way to the local store is killed it has exactly the same significance. When it comes to road safety and traffic deaths we are all cyclists, we share the same risks and we have a common cause.

And the one thing that doesn’t stop amazing me is how fast and easily it happens that when you put someone in a car that he or she can apparently forget that that those cyclists really are people, too. People just like their own wives, husbands, mothers, fathers, sons and daughters.

Bon journée Davide

“a good half of cyclists killed in collisions with a motor vehicle are old-aged people who in the vast majority of cases had neglected their obligation to give way.”

Tuesday, do you mean that the cyclists were elderly and neglectful, or the vehicle drivers?

The cyclists. That is the opinion of the traffic safety institute that conducted a study of all registered accidents involving a cyclist and a motorist.

The result didn’t surpise me. The combination of bad old habits /that perhaps have served them well and certainly haven’t landed them in hospital), slightly weakened powers of concentration and observation and a false sense of safety can be dangerous, As a cyclist I have learned that it is not only young children and teenage girls with their gaze on their phones that can make totally unexpected and crazy moves.

That said, in many of these cases the accident could have been prevented by better road design or if the driver had recognized the situation and chosen to drive accordingly.

As you didn’t name the countries involved I suppose that you just prefer not to do so, which would make it pointless to ask you for a link to the source of the data, given that doing so would disclose the country in case, of course.

However, I’m quite surprised by the huge difference with the situation in Spain (2017-2018 figures), where although most bike users belong to the 40-50 age range, still serious accidents in the samples which were studied in detail come up as concentrated mainly on 20 to 40 years old victims. Most deaths happen outside cities on relatively large roads and in close to 100% the fault is on the drivers: nearly 30% depend on the driver hitting the cyclist while turning, 25% are lateral hits pushing the rider by his or her side, 25% are hitting the cyclist straight from the back (plus a mix of minor causes at 3-5% each, most still drivers’ fault).

Cycling deaths on urban roads were some 15/year. Too much but, in a sense, «not so many».

This doesn’t mean that the above mirrors any general rule, given that in Italy, for exemple most cycling deaths happen on urban roads, instead.

It’s just interesting to know in order to compare and understand.

I am a little sceptical of attributions of fault where only 1 witness survived.

Who isn’t and who shouldn’t be in cases where there is nothing else to go by, but such cases are not too many.

Countries can indeed be different and the population of cyclists does differ from country to country. My two countries are Sweden and Finland. The study I referred to is Finnish and unfortunately only available in Finnish.

(If you’d like to run in through Google Translate and look at the numbers you can search for “pyöräilyraportti 2022”).

For some quick numbers there were 83 deaths in 2016-2020, 65 thereof involving a motor vehicle. The party at fault (according to the traffic law) was the cyclist in 47% and the driver in 53% of the accidents.

There were 15 single vehicle accidents and in 7 the cyclist was legally “aggravated drunk”, above 1.2 per mille or 0.53 mg.

(Only one driver was under the influence, but three failed a drug test.)

Two accidents were collisions between two cyclists, one between a cyclist and a pedestrian.

The type of accident that we all fear and loathe the most, the one where a driver hits a cyclist from the back on a straight road is mercifully rare, 1-2 a year.

Thanks, useful indeed.

The discussion above made me focus on a what is surely an “advantage” of sort for Spain: an advantage, of course, only in terms of road accident stats, but quite the other way around in general terms. Although Spain’s got a high and steadily growing number of cyclists (people riding a bike for whatever purpose), there’s a neat generational divide and the country hasn’t got the same number of 65+ aged cyclists as Italy- not even by far. And in Italy, too, just as in Finland, about half of the cyclists killed on the road are over 65. Probably such a situation factors in hugely in Spain’s impressively good figures (to normalise to population, Finland’s figures should go 8,5x in order to compare to Spain, which would mean some, so to say, theoretical _705_ against 345 for the 2016-2020 period; without making the maths, more or less akin to France and obviously still well below Italy). Older cyclists are very few, which also brings the toll away from the cities.

As for the alcohol factor, it comes as no surprise, either. In Spain, too, 30 to 50% (depending on the different years) of the road deaths are related to alcohol – the difference, according to the fact that the driver’s normally at fault in Spain, is that it was the person on the car who had one drink too much (or several). If other mind-altering drugs are included, the percentage is steadily above 50%. Generally speaking, 2% to 5% of total accidents are alcohol related, but the role played in fatal accidents is impressive. In Italy the percentage is 30-35% of alcohol-related road crashes with casualties.

As for who’s the party at fault, there’s a lot of different studies, too, with percentages varying from 55-45 (driver-cyclist) to 90-10. In Spain, Canada, the USA, Italy (Lombardia) results tended to show an extremely reduced number of accidents caused by cyclists, whereas Switzerland and Australia tended to get the stats closer to 55-45, as Finland above. Of course there’s a lot of different bias which make the subject difficult to tackle, stating with what Nick noted above, then country-specific laws etc.

It should also be taken into account that through the different above mentioned studies the figures are put together in different ways, like including in the total all sort of “road accidents”, that is, including the cyclist who just crashes alone down a descent; separating or not fatal ones from less serious ones (whose characteristics may vary hugely as in the case of DUI’s role); including pedestrian-cyclist crashes among road accidents when less serious accidents are included (which raises brutally the percentage of “cycling are at fault in road accidents”) and so on. Quick example: the figures first published in Italy, which then get referred to and quoted again in most historical series, do *not* include cyclists who don’t die immediately in the crash itself but later in the hospital, whereas Spain always includes victims who died in the hospital up to 30 days after the crash as a consequence of the accident. Which makes the difference between the two countries even more shocking.

All that said, let me conclude that casualties, shocking and terrible as they are, end up being the tip of the iceberg also in a different sense, not only because “famous deaths” represent many more killed cyclists, and the latter, in turn, also correspond to hundreds and hundreds more of seriously injured often permanently maimed. The worst aspect under a general, social, cultural point of view, and both in terms of health and economics, is the fact that extreme events as the above do mirror, surely enough in Italy, a whole system which keeps away people from cycling on public roads, an effective practice whose positive impacts would be broad and huge. Instead, the “conflict for the road” has become, as Tuesday wrote on Tuesday, just another sad example of easy dehumanisation, I’d add, to make it worst if possible, in a context of asymmetrical power distribution. One more, once more.

(Not to speak of the reason which mostly though not exclusively prompted the whole s**t, i.e. capitalism, but that’s a long and different story).

Ps The “driver just running over you from the back on a straight road” Finnish figures could be similar to Spain if translated in 9 to 17 per year, normalising to general population. In Spain they’re typically 12 to 20 per year. It makes indeed sense that these specific numbers aren’t much sensitive to the age factor. In the USA between 2011 and 2013 such a shocking circumstance represented some 40% of the 628 total crashes which killed cyclists, while cycling failing to yield accounted only for 2-3% of the sample.

Very interesting analysis Gabriele – proof that the solution, unfortunately, is not 100% straightforward. It is a very complicated situation and each nation/region has differences. Even amongst nations I suspect there are provincial/state/etc. differences.

Please be safe everyone. Find places you can ride safely, especially around the year-end (Christmas, Hannukah, New Year, etc.) celebrations.