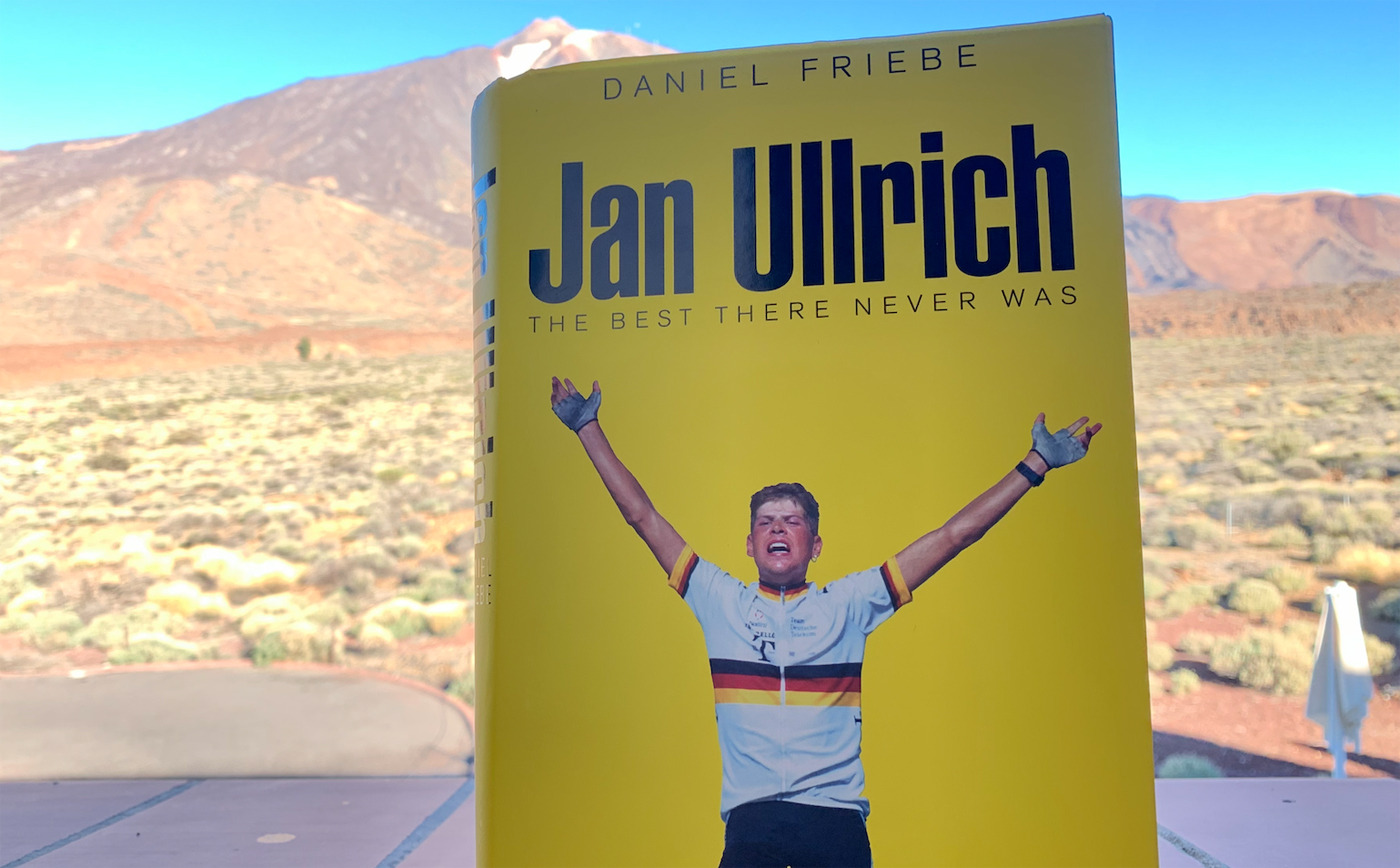

Jan Ullrich, The Best There Never Was by Daniel Friebe

The Tour de France dominates pro cycling, the star around which the sport orbits. Many riders make it the goal of their year, other races struggle for attention. Jan Ullrich’s career was part of this, his first win suggested he’d dominate the Tour, and with it the sport for years to come. Even when he didn’t win, there was always the seasonal targeting of the Tour with his preparation getting more intense the closer the race got.

On a much smaller level the Tour monopolises attention such that when a cycling biography comes out in June, along comes the race with all its distractions. Having bought a copy in late June there was no time to sit back and read it… until now.

If you shouldn’t judge a book by its cover, having bought the hardback you can feel the heft, it runs well beyond 400 pages with notes and an index and the font isn’t big either.

As the title implies Jan Ullrich’s career arc was unlike most others. A Wunderkind who won the amateur worlds in 1993 as a teenager and almost won the time trial against the pros there too, he was second in the 1996 Tour de France, taking the final time trial. Then came 1997 and Stage 10 from Luchon to Arcalis, a ski station in Andorra whose name today still seems to evoke Ullrich’s ascent, the day he rode the field off his wheel, his flat back, a gold earning dangling and the black, red, gold bands of the Bundesflagge on his jersey. For many it was a vision of the future: if he could climb like this, win the time trials, and arrive in Paris with nine minutes on his next rival all at the age of 23 – precocious in those days – then the Tour seemed to belong to him. Of course he’d never win it again.

The book places Ullrich’s life in the wider context, the fall of the Berlin Wall and German reunification are more than a historic and political soundtrack, these events shapes lives. Growing up in East Germany, he’s part of the DDR’s sports system where the most promising athletes, if you can call 12 year olds that, are filtered into sports schools where athletic ability is prized and nurtured more than anything else. When the Wall collapses and Ullrich goes to ride for a team in Hamburg he and his team mates are housed on the notorious Reeperbahn and the contrast must have been astonishing for a 19 year old fresh out of the Berlin sports system.

The 1997 Tour win is symbolic for a country trying to reunite, easterners could see one of their own winning, westerners can celebrate their gain as the first – and only – German Tour winner, it was an act of unification itself. Yet this put him on a pedestal and the move from cheer to adulation, and the risks this brings are well set out in this book. Things fall apart slowly.

At first a series of niggles, hiccups and setbacks, then scandal. There’s injury, drink-driving, a doping ban following an out-of-competition test after a nightclub and the slide begins. Amid all of this Ullrich’s career span took him from the state doping programmes of the DDR, the rise of EPO, the switch to blood bags, and the brief duopoly of Michele Ferrari and Eufemiano Fuentes. It’s obviously intriguing but handled sensitively and well-researched. There’s exploration on when Ullrich might have started using EPO and whether he was a victim of the East German state doping program. The author’s research adds new detail on Operation Puerto and the workings of Fuentes. You won’t look at a chocolate Toblerone bar again but after this anecdote Friebe is quick to add “there were elements of pantomime, like this, but also moments when the sport seemed not so much to have mislaid its moral compass as lost contact with Earth’s magnetic field”.

The contrast in attitudes towards DDR doping days and pro cycling’s leaden years is striking. The book mentions how many doped ex-athletes from the DDR get moral and financial support today. Pro cycling also had endemic doping but once entangled by Operation Puerto – the final verdict would take years – Ullrich never raced again and became a pariah. Now the two systems are different in obvious ways that a book review doesn’t need to cover, readers can reflect on this.

In a podcast episode Friebe mentions that Lance Armstrong looms large in this book and and prior to reading this was a concern, especially if the publishers wanted him to be crowbarred into the story because of his celebrity. It’s handled reassuringly well, it’s not Ullrich via a Texan prism. He’s one of several to talk about his time and there’s plenty from others like Rudy Pevenage, Jörg Jaksche or Rölf Aldag too but given the rivalry for years, featuring Armstrong makes sense. Ullrich himself isn’t interviewed but that might not be any loss, one of the reasons for his troubles with the media over the years stems from him just not being that articulate in set-piece interviews.

At times written in the first person where Friebe explains his research and travels to compile this biography, there’s a sensitivity towards Ullrich throughout, the author can be judgemental about the system but not the subject. All these years later Ullrich seems to be a kid from Rostock who wasn’t ready to handle what would follow; at one point he’s at the Sydney Olympics in 2000 with the German team and at ease in this institutional get-up rather than the garish world of pro cycling, the Telekom team and public celebrity. Whether through early problems like weight gain or the deep personal problems of recent years, at times there’s a temptation as a reader to place Ullrich onto an imaginary psychologist’s couch and diagnose his issues through the pages, especially as the intensity of the book seems to grow with recent events where Ullrich goes from trying to win a bicycle race to coping with life. Friebe sensibly avoids this diagnosis, there’s sympathy but no solutions as the book sets out the struggles with addiction and mental health. There was a point towards the end of the book when I could feel the weight of pages on the left of the hardback spine and how I almost didn’t want to turn further, as if to leave some kind of future ahead.

The Verdict

An engaging and gripping read. Sport is about the celebration of victory but the losers can supply more compelling stories. The rise and demise of Armstrong has been told many times over, Jan Ullrich’s story less so, particularly in English and the author with his language skills and Berlin residency is the perfect writer. This book tells a story of Ullrich with themed chapters that are well-researched and written with polish as they blend the micro with the macro, from details on winter weight gain, to new light about blood doping practices all the way to to placing Ullrich’s life with the social context of German reunification and this breadth makes it one of the best cycling biographies of recent years.

- It’s published by Pan MacMillan and available in hardback, ebook and an audio version

More book reviews at inrng.com/books

I guess I’d need to read it but frankly from what inrng reports the focus on DDR doping and so on looks laughable at best, especially when speaking of a prominent Telekom athlete.

Just a name: Keul.

Of course, only Fuentes has been *proven*, but just as Friebe “explores” the DDR leit motiv, why don’t explore this also rather promising subject, given that Ullrich had quite much a stronger relation with the Telekom team than with the DDR, be it only due to mere chronology?

I’d be curious to read if any specific facts are presented in order to especially relate Ullrich to DDR State doping or it’s rather “connecting the dots”.

Because if we’re connecting dots, Keul (& friends) is way more interesting, and pretty much forces any serious analyst to bin for good the stereotype about the DDR as a peculiar case in State doping as opposed to what was happening in, say, West Germany… or in Italy.

Imagine that DDR doping doctors were trying to convince decision-makers to allow specific doping use (and succeeding to do so)… because Keul was promoting it!

As you say, you need to read it. I thoroughly enjoyed it and it certainly isn’t an assassination piece on the DDR, which, if I understand you correctly is what you’re assuming? Obviously doping is a key topic but mainly because of the times not solely because he was born in the DDR. I got the impression that the author went to great lengths to not make this book an “East Vs West” narrative. For me it’s one of the best cycling books I’ve read in a while.

As I also said, it may well depend on the review, but just check the insisted presence of “DDR” above. When the Berlin Wall fell Ullrich was still 15 (!)… Although cases of doping on minors in the DDR were actually reported, the doping angle looks totally misplaced here, especially considering the Keulephant in the Room: Ullrich spent a couple of years in a KJS, at most three, as an early teenager, whereas pretty much his whole pro career happened at Telekom / T-Mobile over more than a decade.

So, what’s really the relevant context to “explore” here?

(as in: “There’s exploration on when Ullrich might have started using EPO and whether he was a victim of the East German state doping program”).

I won’t further comment on “The contrast in attitudes towards DDR doping days and pro cycling’s leaden years is striking” because I went some length on it below.

PS “Not solely” frankly made me laugh. Note the disproportionate relative weight of whatever *supposed* doping Ullrich *might* have experienced when 13 to 15 in the DDR, and… the huge rest of his sporting experience – including lots of proven facts about him himself and his team – but now we’re *even* speaking “doping in the DDR”: that explains better than anything else what I’m trying to communicate about perspective, stereotypes, idées reçues and so on. Barely a mention about the role of “Western” universities, medical national institutions, Olympic committees etc.

Barely a mention, again it’s in the book when it comes to universities etc. The possibility of doping in the DDR days is perhaps more about Ullrich’s upbringing as a child and the person he became, but as suggested above, the danger is ersatz psychology.

As Wayne says, it’s worth reading the book, especially as Keul is there without wanting to spoil the reading for others.

As for the rest above: so I guess it was rather about the review 😉

Let’s leave the Keul and Southern (Federal) Germany universities surprise to the readers of the book, then. Whereas no spoiler alert is needed when associating DDR and doping, indeed.

However, *unless* serious facts are brought forth by Friebe on the subject, I still find that speaking of a couple of seasons as a teenager in a State Sport School as a meaningful doping-related point is just poorly reinforcing commonplace assertions, especially given that the subsequent twenty years or so showed that Ullrich was *actually* being doped in every sort of other system (and the passive voice is also especially relevant here), *plus* that athletes from any sort of background became “that kind of person” without any help from the DDR. So, where’s the correlation?

But that’s enough from me – for now 😉

At the risk of ruining the book for others, the story is more about a young man who was unable to cope with the sudden fame and fortune that was thrust upon him. Doping is more of a background story, as you would expect from a cycling story from the 90s, it certainly isn’t the main issue covered in this book and it certainly doesn’t lay the blame at the feet of the DDR. There’s plenty of stuff about Telekom and Fuentes and you certainly don’t come away thinking “if only he’d been born in the West”. As I said previously the author went to great lengths to not just make the book a lazy finger pointing job at the old East. Read the book it’s great! 🙂

Hey, I *still* ride with one of those gorgeous Team Bianchi jerseys (portraited), and not exactly because I am any fan of Casero 😉

And what about this…?

“The contrast in attitudes towards DDR doping days and pro cycling’s leaden years is striking. The book mentions how many doped ex-athletes from the DDR get moral and financial support today. Pro cycling also had endemic doping but once entangled by Operation Puerto – the final verdict would take years – Ullrich never raced again and became a pariah.”

If you want I could also name several doped ex-athletes in cycling and beyond who get moral and financial support today… without having ever had any relation with DDR, imagine that.

Whereas, as the piece above shows, having been part of the DDR Sport System is enough to start speaking about doping.

I think that if there’s a contrast in attitudes of sort to reflect about is how singling out DDR allows us to “forget” all the time what USADA was doing, or CONI and so on and on.

Contrast of attitudes? Wasn’t Ivan Basso involved in OP? And let me be clear: I consider it fairer to treat people as “we” do with Basso than as it happened with Ullrich.

And what about the consequences of all that surfaced about Sky and British Cycling? (…Consequences? What consequences? A couple of scapegoats?)

Post Scriptum

By the way, as this goes about doping & cheap narratives, and also speaking of Parliamentary Commitees and what can come up through them, perhaps what gets recorded in the recent report of the Italian Antimafia Parliamentary Commitee might prompt a revision of Rendell’s book on Pantani, and its underlying decision to base strongly its perspective on institutional cues by police forces which worked on the case.

Think you’ve got the wrong end of the stick here, but perhaps I should have explained things better, especially as doping is always a topic that provokes reactions.

Germany has Doping Opfer Hilfe, literally “Doping Victim Help” and it’s run almost on similar ways to those who might have been given wrongful medical treatment. This is an institutional level of financial and moral support that I’ve not seen in pro sports whether it’s cycling, tennis, athletics etc, but for many reasons this is not going to happen, because it’s not the state that’s perpetuating it, because some victims because wealthy through it and so on.

The point is that when doping is strongly related to some of the State’s power structures (as it was in the DDR, for sure… and pretty much everywhere else) it becomes harder to tackle for a series of reason. Besides, you can’t always count on institutional sources to achieve a reliable version of facts. However, of course a State is composed by different power structures and groups of interest, and so it’s still possible that the wheel goes on turning and people end up being investigated all the same. It’s “the same USADA” (not exactly *the same* of course), covering up doped Olympic medallists or catching Lance. Just as the CONI covers Conconi and then some years later they themselves do corner Basso.

What’s sure is that we’re speaking of a whole different level when compared to that of dopers like, say, Di Luca with his Santuccione…

Doping Opfer Hilfe (essentially focussed on victims of State doping under the DDR) is probably one of the best possible examples of the serious issues which may be fostered by this kind of notable (and declared) ideological biases. The good thing is that at least they apparently have recently started having an internal debate on the subject, although the bad thing is that it quickly escalated to a feud. It’s an irony of sort that they were founded the same year when Keul was elected President of the German Association of Sports Physician.

Well apparently Gabriele is very sensitive about East Germany… As Inrng often says, it gives more informations about you than about the subject when you react so strongly to what is at worst a slightly deflected review of a book you didn’t read.

I understand you’re not wrong, but it seems like it’s a very important subject for you. A small picture of Walter Ulbricht with His Antikapitalist and Antiformalist glasses may calm you down : https://media2.nekropole.info/2015/08/Walter-Ulbricht_55cbba0637df0.jpg

Well, not especially – it tends to be interesting as it’s a classic in ideologically skewed representations and comes up relatively often. Plus, I’m a long-time Ullrich fan, so I’ve followed him as an athlete for well, decades now.

I wouldn’t say that it’s “slightly” deflected, as I explained above. Doping is one among the lead themes of the piece (obviously), and the DDR is being related to that (not as obviously), while other *strongly* related subjects, albeit present in the book (dunno to what extent), hadn’t appeared at all before I named them, despite being by far more relevant both in Ullrich’s history and for their general interest regarding “sport medicine”. But this is frankly becoming meta-boring, i.e., mega-boring.

Being anticapitalist? Sure, and proud, but in case I could choose I’d always pick as a political model Rojava or Chiapas over DDR or the USSR ^__^ (Signora libertà, signorina anarchia).

OTOH, this piece led me to think about what’s the possible relation between inrng and the ex Soviet world he knows or is interested in more than most 😉

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UyYCD3fDMwE

Got the book sat waiting for me to read it, been a fan of Friebe since the start of the podcas, but mainly came here to say

“could feel the weight of pages on the left and how and I almost didn’t want to turn further, as if to leave some kind of future ahead”

Was a wonderful turn of phrase, that the likes of Friebe would be proud of.

Agree with you on Freibe, the book is excellent and I feel like he has really come into his own on the podcast since the sad passing of Richard Moore – the offseason cycling podcasts have been thoroughly enjoyable!

Thanks for the book review – always a useful help for purchases.

It’s a shame that Ullrich himself is not given a chance to talk. Maybe a non-sports journalist would get more about Jan the man, as apposed to Jan the cyclist.

I found it to be engaging, thorough, and surprisingly academic in tone (not a bad thing!). Tricky to get a hold of a copy in North America, but well worth the effort.

In the US, I see it’s always on amazon from 3rd party sellers and there’s a kindle version too.

Definitively looks like an interesting read and a great interview inrng.

Read the quick sample and asked for it for Xmas.

From what I have read it is a very eye-opening book about Jan, the way East German manufactured Olympic athletes, how talented he was/is especially as a neo-pro and other behind-the-scenes info about him.

For all the righteous comments about doping – get real. You’re missing a grand story about a true cycling champ.

I’ve always found Ullrich interesting, and certainly a much easier person to pull for than LA. Looking at his results on Wikipedia, it’s striking how few Classics he did, especially Ardennes classics. Anyone have any insight into that?

I’d could suggest the Tour was just the big focus, things seemed much more separated where other Tour contenders would miss the classics too, and that Telekom had such a strong team that they had others to do the classics. But one specific reason could be the weight factor, he was often uncompetitive until June and the Tour de Suisse as he tried to lose the weight gained over winter, breaking his body down with long rides rather than honing form and he didn’t do much in the early season stage races either; his results in one day races were best in the summer, eg the Olympic road race win.

It is striking, yes. I only can assume that Ullrich first of all had no socialization with those classics races as a kid when those races did not appear on any sort of media in the GDR. When the wall fell he became famous and part of a mass media team/ phenomenon aka Team Telekom which jumped a train and sadly to mass media in Germany such things as the classics do barely have any relevance. Maybe just if Zabel wins san Remo for the umpteenths time.

Good point too, Ullrich and others at the Berlin sports school were forbidden from watching the Tour de France because it was on West German TV… so of course they watched it and the book explains the antics they got up to with the TV and aerial etc. But the spring classics would have been harder to get.

Thanks!

In the end I think he was just one of a very motley crew. But having said that he seems to be faring better than Boris Becker … even if only marginally!

Hello. I’m about 100 pages in. It really is a good read. I’ve read almost all the cycling biographies and autobiographies and this is right up there.

Friebe has done a great job. I wasn’t going to buy this book but after hearing him on a podcast talking about the process and background, and then seeing Jan on Armstrong’s podcast I got inspired. I’m glad I did. Thus far a great read.

Personal anecdote with Jan a few months before he won in Oslo: I was DS for at Danish team at the 1993 Tour of Bohemia. We had some really good riders or so we thought…

On stage 2, I had left the convoy for the feeding zone. Standing by the road side, one rider passes; Mr. Ullrich, and the feeding zone starts buzzing; “When are my riders gonna pass?” – Well, eventually they did show up and were handed their bags – 19 minutes later!!!

He rode the full peloton 19 minutes off his wheel – at 18 years old. And the rest is history, as the saing goes.

Thanks INRNG for the review and to Gabriele for reviewing the review.

I enjoyed the book (although, be warned, if audiobooks are your medium of choice, it’s not the author reading). I’m not sure whether it’s a feature of biogs for people still in their middle years, but the book has an air of a story that ended when the publisher lost patience rather than one with a specific conclusion. Maybe it lends itself to a later update.

A recommended read.

I couldn’t put the book down, not only because of depth of emotion in Ullrich’s story, but also because I knew (via the Cycling Podcast) how what it had taken for Daniel to get it done. For anyone that wants to listen, Daniel’s prelude to publication was posted on June 6th 2022 (S10, Ep 64).

Interesting to see Ullrich’s current rehabilitation path. The book details at length the opportunities that he had to acknowledge his own story and move on (like Armstrong and others) but he never took them. It’s nice to see him out on his bike and seemingly enjoying life but I wonder at what point he will put his own side of things down on paper (or more likely on streaming video).

That 1997 Tour was the first one I watched in full and in many ways it’s still my favourite. One of the things that I can remember about it was the commentators constantly banging on about how surely Ullrich would dominate the Tour for years to come and was the new Indurain. I always liked his style and to this day on group rides if anyone is going up a climb in the big ring I call them ‘Jan Ullrich’. The book sounds like a good read, if lengthy. Maybe one to take on holiday.

Excellent read, handled with sensitivity and rigour.

I kind of thought I was done with the decent cycling biographies as all the celebrated winners and interesting characters had been done but it turned out, as an English speaker, I knew very little about Ullrich and, indeed, about Germany and German sport.

This book was well overdue and very much appreciated and enjoyed.

Very happy you reviewed this.

I listened to the podcast interview on it and enjoyed, but as I rarely read biographies and almost never read factual cycling books (I’m a fiction person at heart, despite having read Slaying the Badger) I wasn’t going to read this and may well do so now…

Coincidentally I happened to see this post on the same day I noticed that generations times up many of the most famous climbs – Ventoux, Alpe d’Huez – still stand, I was genuinely suprised that Froome’s 2013 Ventoux as well as Vingegaard and Pogacar in 2021 was so far down this list. Obviously heat, wind and competition mean you can’t compare like for like but still fascinating how the EPO/Blood doping generation cast such a long shadow across cycling in so many ways.

It’s good to hear the personal stories though, even if I wish one day non-cycling fans wouldn’t respond to every cycling conversation with ‘yeah but they all doped right?’!! (Admittedly Ulrich’s suffering caused by that era far exceeds my own discomft of being a cycling fan.) I’m interested to see whether the current doping investigations in Spain which seem to have caught up with Superman will drag in wider sporting stars from Barca’s golden era and tennis.

Total aside – the above Ventoux/Alpe D’H results also took me down a W/Kg rabbit hole after being suprised Froome was slower on Ventoux in ’13 than Contador in ’09 but faster than V/Pog in 2021.

Even if W/Kg are a magical art I know little about and probably misunderstand, from general Froome articles he seems around 5.9/6w/kg over at 30-45min period of climbing and Pog seems only slightly higher, I had expected him and Vinny to be more significantly above, similar to what Lefevre thinks Remco is at, having said he hit 6.5w/kg in Denmark this year over 30mins. I’m fascinated to see Pog vs Remco vs Vin, so just having fun looking at numbers I do not really understand.

Devoured the book as soon as it came out. I think it’s exceptional. So well researched with wide and deep social context throughout.

Honestly, the chats with Armstrong are where it really comes alive. Friebe transcribes LA’s manner of speech and you can really hear that brash Texan know-it-all tone jumping off the page; in a good way!

Friebe knows the burden of dealing with this famous, flawed, controversial figure and handles it so well. It’s why it took him so long to write! It’s spot on.

The book is very good, brilliantly researched and excellently written. It is definitely worth reading, if only to learn more about German sport and the perils of fame. You’re right, the Armstrong sections elevate it further.

I know it will rile people up on here but LA comes across well in the book at least with respect to his relationship with Ulrich and his efforts to help and support him in his struggles. It may be an element of LA’s sociopathy expressed through a mafioso-style loyalty to those that were loyal to him. I’d prefer to think of it as it being possible for people to be more than one thing at once. Of course LA was a cheat and a bully, a hugely flawed human being. But he also shows compassion and a willingness to help a former rival that speaks well of him.

100% agree, really looking forward to reading this.

There’s the risk of trying to diagnose Armstrong’s motivation as much as Ullrich via the pages as well but whatever the reasons, he’s been helping Ullrich and from the sounds of it while he’s put some of it social media and in his podcast so people are aware of this support, some parts haven’t been shared as much.

Thanks for bringing this to our attention. Doping aside, Ullrich is an interesting person. LA is vilified, Pantani praised and Ullrich’s treatment seems to be somewhere in between. I’ve never quite figured that out. They all doped heavily, as did many other cyclists at that time. Their personal characteristics are a lot more interesting than the doping. Ullrich burst onto the scene at the 96 Tour and triumphed in 1997. We had limited coverage of races here in North America in those days and I’ll never forget Riis throwing his TT bike when something went wrong with it in the 1997 final TT. That and the Telecom team dominance with Ullrich, Zabel in green, etc. I’m going to put the book on my Kindle so I can read it on my plane trip to get back on the bike when I go somewhere warm in late February.

There’s a variation in how people get treated after doping scandals and many factors, one big part is how the individuals cope, deal and explain it but the book also explores some national angles here and why it’s been awkward for many Germans/Germany; in part because they bought in so much but also a legacy of history. You’ll need a long flight to read it, or rather it’ll be a good post-ride read.

And situations change through time, Pantani was literally destroyed by the press and TVs in Italy (he was “il dopato d’Italia”) in the aftermath of Madonna di Campiglio, and his institutional canonisation – always partial, disingenuous and ambiguous to sat the least – happened essentially after his death, several years later, and grew through time. Different angles on what happened also surfaced and forced some shifts of narrative, although – sadly enough – not for everybody.

Armstrong, on the contrary, was well treated when he had embarassing issues during his most successful career span, and, anyway, it’s hard to say that even at the end he was treated worse than he deserved.

Wow – where is that desert in the main pic?

Teide, the volcano in Tenerife, Spain.