The War on Wheels, Inside the Keirin and Japan’s Cycling Subculture, by Justin McCurry

Keirin racing might appear on your radar for the annual track world championships, or even just for the summer Olympics. In Japan it’s a way of life for participants and punters alike, one of only four sports where betting is allowed. This rewarding new book takes look at keirin as a sport, as a business and along the way holds up a mirror to Japanese society.

Travelling in Japan, to ask about keirin tracks was to lose eye contact. Whether it was a friendly desk at Fukuoka railway station, a hotel reception in Hamamatsu… or even visiting a good friend in Ginza, a gaze was averted. Was it something I said? Had I mispronounced keirin and was instead asking for something absurd or even deeply inappropriate? Over a cold glass of koshu my friend explained keirin venues are often seen as dens for down-on-their-luck gamblers rather than sports arenas, the kind of place a visitor really ought to avoid. No tourist professional or concierge tasked with promoting the country or their home town would dare suggest a visit.

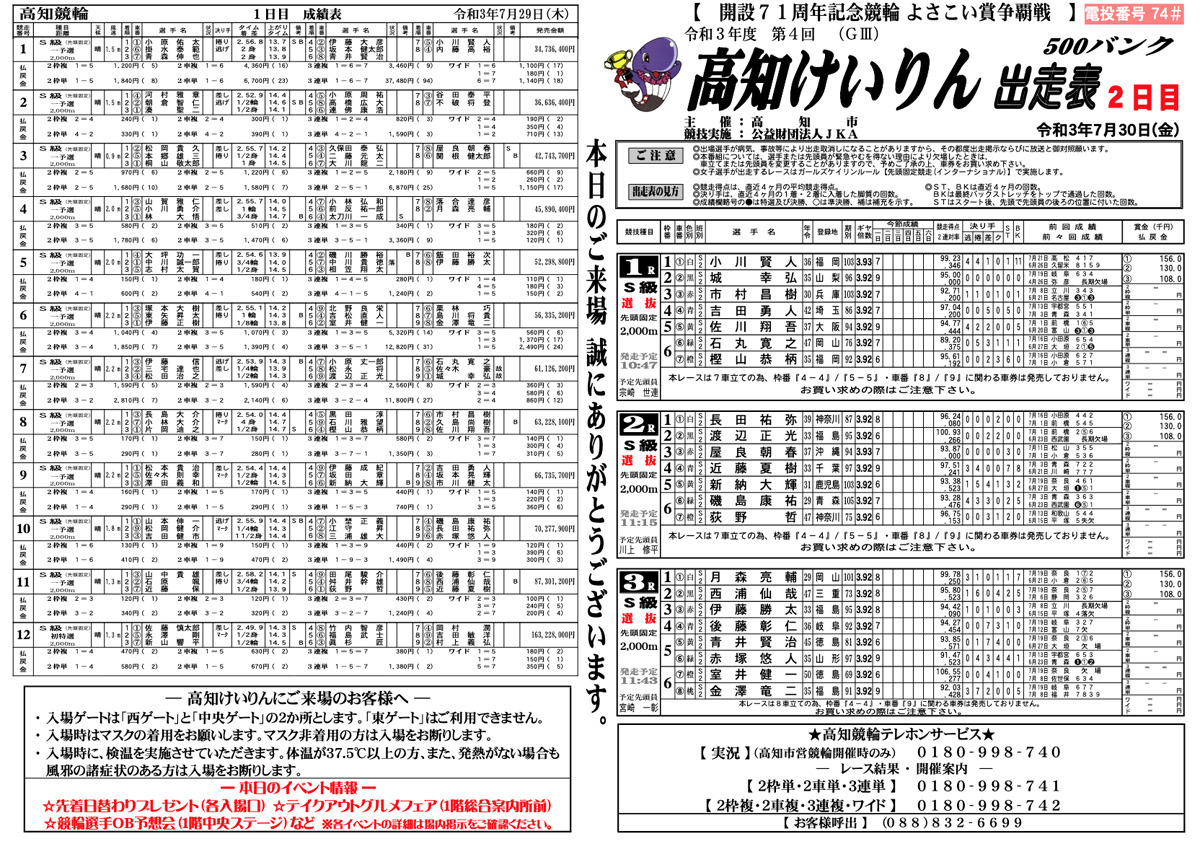

Keirin is a bicycle sprint race with nine riders on a banked track but it’s much more, an institution complete with apprenticeships and a role in society, although an unloved one. Sports betting is highly regulated in Japan and only allowed in horse racing, motor-boat racing, motorcycle speedway and keirin track racing. Keirin’s core audience is old and getting older, poor and because of gambling, poorer but it remains a big deal.

‘My life is on the line here!’ he yelled. He was one of many nuclear plant workers who spent their off days at the velodrome

This book carefully explains the history of keirin, an import from Europe built in the ruins of post-war Japan to generate tax revenues to rebuild cities, albeit with the money often coming from poor workers and unemployed former soldiers.

Is keirin a sport or a means of gambling? It’s both. Superficially it might easy to see it as the latter where, instead of nine cyclists on a track, punters might equally bet on marbles rolling down a tube or donkeys in pursuit of a carrot. There are no superstar cyclists, no household names and certainly for a tourist it’s easier to pick three numbers for a betting slip and hope for the best. 5-3-8, or maybe 2-8-5?

Yet underneath the Mario Toad-style helmets and oversized jerseys is more than a cyclist in body armour. There’s a whole system that began in the bombed ruins of Hiroshima and today starts with an apprenticeship at the legendary keirin school on the Izu peninsula. There’s has a codified system and career path similar to the sumo ranks and the makuuchi rankings. Seniority and regional rivalry shape race tactics. For punters dense form guides supply data like recent results but you can use thigh circumferences or even blood type to inform your wager. The year ends with the Grand Prix and, for once a prize worth of the label: 100 million Yen for the winner, not far off a million US dollars and surely the biggest cash prize in all of cycling?

The book does a good job explaining everything, it’s educational but doesn’t cram; although if you read pay attention to the initial explanation of “the line” as knowing the terms senko, makuri and oikomi helps later on.

Gambling, rules, bikes, rankings and job opportunities make keirin racing very different from the short sprint we see in the Olympics and Worlds. As McCurry explains, keirin in Japan is 競輪 which uses two pictorial kanji: one signifies a match, the other a wheel and so you get a bicycle race. But the Olympic-UCI keirin is spelt in Japan as “ケイリン” using the angular katakana syllabary deployed for imported, foreign concepts, like, say, “テニス” for tennis or “アイスクリーム” for ice cream. This is more than linguistic trivia, it signifies a fundamental difference between the domestic and international versions of keirin that is literally spelled out. The book subtly explains all the differences along the way from rules to kit and avoids any blunt side-by-side comparisons.

The author has been a foreign correspondent writing for a British audience and this is evident a few times, evoking the unflattering reputation of Saitama, a commuter city part of Tokyo’s sprawl, McCurry compares it to Essex in England; also there a few moments where a paragraph feels like it is repeating something you’ve read earlier. Yet overall it is very well written. McCurry has been Japan since 1991 and it shows, this is not a foreigner parleying Wikipedia and Google hits into a “Look! Japan! Keirin!” book in time for the Olympics. It’s written an established Japanese resident with deep knowledge of the country and language. Much of the book places keirin in context and along the way there’s imperial change, economic history, demography, diplomacy and it explores the role of women in Japanese society over the years, whether at the first keirin race or the recent introduction of “Girl’s Keirin”. It runs wide and is all the better for it, especially because McCurry is trained to explain these matters to a readership abroad for his day job, there’s an eye for the telling anecdote or metaphor.

For all the explanation of keirin and track racing technicalities this is also ode to Japan. Others may celebrate, say, the cuisine or manga, this is one for the people, especially the būrū-kara blue collar workers and pensioners trackside with their pencils and cigarettes hoping for a windfall, and the artisans in backstreet workshops staying up late into the night to craft steel frames. There’s a wistful tone at times, just as keirin grew during the post-war boom culminating in 27.4 million attendees at the end of the bubble, today it’s down to 4.2 million and dwindling, just as other parts of Japan are also dwindling after the boom years. Still that could be four million more than the combined attendance for track racing across the USA and Europe where six day racing and other meets have gone from mass popularity to a marginal activity that pricks public consciousness every four years with the Olympics, and where terms like madison, pursuit and, yes, keirin, must bamboozle audiences expectant of a medal yet often unable to explain how it is won. Keirin though is much more anchored into Japanese society and here’s the rub: if it shrinks then many velodromes are in trouble, cities even lose a revenue source for social programs. A specialist training academy and even a way of life for many could be lost. This is a story of institutional decline rather than a mere change in leisure tastes and here keirin overlaps with other parts of Japan struggling with huge change, where rural villages to corporate giants like Sony.

The Verdict

An excellent book that goes beyond the velodrome to look at keirin’s place in Japanese society. It’s well researched and an easy read. Cycling fans will learn plenty about this big area of track cycling which deserves a book in English, there’s too much to cover for any glossy magazine spread; or blog post. Japanophiles keen for niche coverage will get their rewards too.

The War on Wheels is a story of modern Japan and that blends sport, culture and history into a subtly convincing mix. Start the book as a track racing neutral today, read briskly you’ll finish it certain to watch the keirin finals in the Olympics next week and promising yourself to watch the Grand Prix at the end of the year. And should you visit Japan one day and visit a keirin track be sure to report back to your hosts that you enjoyed the evening’s sport and see what they say.

- It is published by Pursuit Books in the UK and Pegasus Books in the US and available in hardback and e-book.

More book reviews at inrng.com/books

Thank you kindly! Japanese keirin has fascinated me for years. Nice to find this book at a nerdy Norwegian web shop. Ordered.

Sounds promising. There are good documentaries online about keirin racing, I liked the one with Chris Hoy.

The Hoy one is good, also one from Eurosport with one of the French sprinters, François Pervis I think, and in several languages, plus the rabbit hole of Japanese documentaries from the 1980s on Youtube which anyone can enjoy because of the scenes of the dreaded uphill training, the roller drills etc. But they skim the surface, this book goes much further in explaining things… for example the famous slope is also used downhill where riders must master wild cadence on the way back down.

I simultaneously added a comment about the Hoy doc! Thought he was going to break that static bike when he was doing a max effort. Oooof.

Shane Perkins did one too.

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLhx501eEyTnEICY-XZtqq43PNm5YlBary

Many thanks for the link, really enjoyed that.

Thanks, added to the reading list. For any UK-based readers there’s a keirin documentary with Chris Hoy on the iPlayer which is worth a watch.

The main thing that struck me is how similar the feel and clientele is to a UK dog track (greyhound racing). They aren’t there for the sporting element.

That also dictates equipment with rules dictating everyone rides the same steel frameset and box-profile rims. Presumably to maintain a level playing field for gamblers and keep costs down for the organisers.

The bikes are old – although they have “evolution” races that allow modern kit – so that everything is equal, a rider can’t suddenly get better because they bought a new helmet or frame and those gambling won’t feel they lost out because someone secretly, say, used a new chain wax or something else that can’t be spotted. So it’s retro but for a reason, the level and especially consistent playing field.

There’s life in the old quill stem yet…

My wife went to Japan for academic reasons awhile back and had the same experience. Asking to be taken to a velodrome to see Keirin racing seemed like she wanted to be taken to a brothel. When she finally got someone to take her the atmosphere was just as described. She was able to yell encouragement at one of the competitors who meekly waved back….as noted the atmosphere is all-business…or really all-gambling. Not the Kentucky Derby but more like a dingy dog-track somewhere.

I’m currently reading the book having read about it in the Guardian newspaper, and I am very much enjoying it and highly recommend it.

Thanks Inrng for adding more context around Keirin and how it is viewed in Japan, as it would certainly be on my list of just things to see should I visit Japan.

I also echo the above from he other posters that the Chris Hoy documentary is worth a watch, though I was hoping for something a little longer in length.

Fascinating. Straight to youtube – ‘keirin grand prix’. I’ve watched a few before, and read rumours of race-fixing. Anything in the book about that, or any truth to such rumours?

The whole thing is designed to avoid this, confidence in the sport would collapse the moment the punters suspected anything. The book explores riots in the 1950s when this happened and the creation of the riders’ school, the isolation pre-races and more.

Interesting, thanks.

They should move with the times and upgrade the whole thing to BMX!

In the UK media, Essex is the standard unit of measurement for slightly rough and ready areas near to a big city that are home to large amounts of commuters, some heavy industry, and a bit of countryside the further you move away from the city. (i.e. it also regularly compared to New Jersey). Being Essex born-and-bred and having spent some time in Saitama I can confirm that Saitama wins the comparison hands down.

Similarly, Wales (or sometimes Belgium) is used as a standard unit of area (e.g. In the Amazon, an area half the size of Wales is burnt each year).

Read it, enjoyed it.

There’s that sense everyone knows they have a problem with the ageing and shrinking audiences, they can’t work out what to do, audiences keep shrinking.

Enjoying it while it lasts.

It strikes me that the aging and shrinking audience for keiren, and the waning interest in its traditions, is part of much larger trends in Japan: a rapidly aging population, low birth rate, “lost decades” in the business world, etc. It evokes a sense of melancholy, but such is the way the world moves.

An excellent photo essay here from Tim Bowditch, https://www.timbowditch.com/big-dream/

It does convey the atmosphere there, thanks for sharing this.

There’s only one photo of the athletes in the whole photo essay, perhaps very be fittingly.

Loving forward to reading this, thank you for the review.

The Cycling Podcast’s “Service Course” has Tom Whalley talking to the Author this month and it’s a great listen. McCurry himself differentiates between the Japanese and the UCI sports via pronunciation – ”Kay Rin” for the domestic, and a more westernised “Kie Rin” for the UCI which I found useful.

Keirin should be kei (rhymes with day) and rin (with bin)… kierin / kirin in Japan is a popular beer named after a mythical chinese unicorn… but also means a giraffe 😉

Bit late to this but thanks for the review and highlighting this book. I guess I could read it myself, but I’ll ask a question… does it cover why Japan seems to have relatively little success on a global level for track cycling? I’d naively assume that it provides financial support and training for a big talent pool, which would then self-select the some great riders. Hoy said that he never won a race during his stay at keirin school, which suggests a decent level of competition. Is a different skillset needed to win domestic keirin?

Yes it does cover this, the short version is the two versions are so different and there’s little incentive for Japanese riders to cross over, to give up their day job. The level is good, foreign riders can and often do win in Japan but they don’t get to race the very highest level events. The book explains alot of this and one solution to keirin’s decline could be opening it up, to have audiences in Australia, the US, Britain, Germany etc… and betting income?

I’d had the same question. I would have guessed that the relative popularity of the sport in Japan would lead at least some young men to be excited about track riding, with the result that there’d be some spill over into other forms of cycling. Kind of the same way some road riders started with an interest in mountain biking, and then generalized a little. But I guess the shady reputation of keirin means it’s something that young people aren’t much exposed to, and I imagine there are no amateur Japanese-style keirin races. Is the desire to be a keirin rider in Japan somewhat like the desire to become a jockey in the horse racing world (i.e., not something anyone does for fun, or because they love it)?