Brittany is a region that ranks alongside the Basque Country, Flanders and Tuscany as one of the hotbeds of cycle racing. Many riders in today’s peloton are from the region, several champions from the past hail from here, two teams in the Tour have a Breton identity, another has a Breton sponsor while one of the Tour’s jerseys is sponsored by a Breton firm.

Brittany is the region that juts out into the Atlantic, home to 3.3 million people in France, a country of 67 million. It’s roughly double the size of Flanders, with half the population. Regions in France are administrative creations and can often feel like it. Brittany doesn’t, it’s got an authentic identity. A kingdom from the 9th century on, today there’s a Breton language, a black and white flag and a Celtic background that’s visible in town names and typefaces alike; and audible with the biniou and cornemuse, bagpipes in English.

Most French people are proud of their home region, but polls regularly suggest Bretons top the list when it comes to local pride. This supports the “loud and proud Breton” stereotype. It can confound outsiders, the terrain’s not too exciting, the food and wine isn’t famous – more agribusiness than terroir – and the economy is prosperous but middling. Plus it rains a lot – “the weather is nice several times a day” goes the joke – so it’s not a region that seeks to impress. But that’s sort of the point, it’s not about whether outsiders like it, the locals do. Pride loops back to the Breton identity rather than other features.

How cycling as sport became so popular isn’t obvious. There’s the usual mix of industry and agriculture at the end of the 19th century where many workers are able to afford a bike as a means to get to work, this holds true across other parts of France, Europe and the world beyond. Manufacturers started using races as a means to promote their bikes and tires but the sport didn’t get an immediate start in Brittany, most races were closer to Paris. In 1891 there was Paris-Brest-Paris, the 1,200km race which only underlines how far Brittany is from the capital. Some like to draw a link between the Breton culture of celebrating strong, outdoor work whether farming or fishing, and cycling with its tough image of the cyclist out training and racing in all conditions.

The first Breton champion was… from Argentina. Lucien Mazan was born in Brittany but his parents moved to Argentina in search of a fresh start, not unusual on this Atlantic peninsula. After winning a bike as a prize he took up racing against his father’s wishes and gave the pseudonym “Breton” to avoid being noticed. He thrived and soon moved back to France hoping to become a professional cyclist. Confronted with another pro called Breton he renamed himself Petit-Breton and quickly rose up the ranks, winning the first Milan-Sanremo in 1907 and later that year the Tour de France and a repeat win the following year.

The post-war period saw Jean Robic – born in the Ardennes on the other side of France but a Breton – win the Tour de France in 1947 and then fellow Breton Louison Bobet took three in a row in 1953, 1954 and 1955. There was a steady flow of smaller wins in the following years, think Tour de France stages, spells in the yellow jersey and classics from the likes of the Groussard brothers until Cyrille Guimard came on the scene, a great racer and arguably the greatest team manager, a point he’d probably argue.

Then Bernard Hinault arrived. If you take the Breton stereotype and exaggerate it you get Hinault, the snarling champion who could bend any race to his will and still makes life difficult for French riders today with his sharp quotes. Although a recent feature in L’Equipe suggested it’s not really out of malice but more his way of tough encouragement. It saves bandwidth to cite Milan-Sanremo and the Tour of Flanders as the races he didn’t win. He won the Tour de France five times and is the obvious “best Breton cyclist” given he rates alongside Eddy Merckx and Fausto Coppi as the greats in any measure. In English both William Fotheringham’s biography and Richard Moore’s “Slaying the Badger” are entertaining and informative reads.

Just as not everyone in France likes football, not everyone in Brittany is cycling-mad either. But many are, read local newspapers like Ouest France (“West France”) or Le Télégramme and cycling is up there with le foot for column inches, whether it’s World Tour transfer news or a village race result. Parochial? Maybe but on a giant scale, Ouest France by the way is France’s biggest selling newspaper, its circulation is doubles national dailies like Le Monde and L’Equipe.

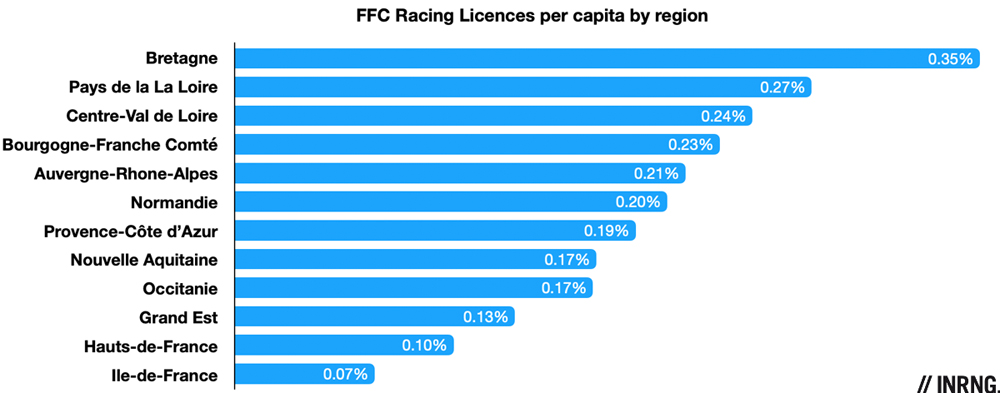

A share of the audience are cyclists, Brittany has the most FFC racing licences per capita, and by some margin:

There are other federations and many just ride with friends rather than seeking out a club and then a federation, but still the chart is a proxy for cycle sport activity in France. Look elsewhere and the region has got the the World Tour race the Bretagne Classic (ex GP Ouest France Plouay) plus the Tro-Bro Leon race, the Grand Prix du Morbihan and these are the races at the top of a pyramid, what impresses more is the vast number of U23 and amateur races for all categories. Locals complain about vanishing races and for all those racing licences, the count is falling, a point also made in this morning’s Le Monde. Although it’s relative, Brittany is holding up better than many other regions.

Today Riders like Warren Barguil, Audrey Cordon-Ragot, David Gaudu and Valentin Maduouas are from the region and over a quarter of the French riders on the Tour startlist today are Breton. The UCI President David Lappartient is a Breton. Junior Eddy Le Huitouze is a name to watch for the future. The Arkéa-Samsic team used to be the Bretagne Team, sponsored by the region and its two title sponsors today are Breton companies. The B&B Hotels team also has its HQ in the region. Meanwhile the Intermarché-Wanty team is backed by the Belgian arm of Intermarché, a French supermarket chain from Brittany. The polka dot jersey in the Tour de France is sponsored by Leclerc, another supermarket that began in Landerneau… coincidentally or not it’s today’s stage finish town.

It helps explain why the Tour is here because the 2021 grand départ was going to be in Copenhagen but this had to be moved to 2022 and Brittany was only too willing to step in, if Christian Prudhomme needed to find a region ready to host the Tour at the drop of a hat (and a drop of the hosting fee) then Brittany was the obvious choice. Several newly-elected green mayors have spoken out against the Tour de France for its commercialism and carbon footprint but the Breton ones seem to have backpedalled more… they know where their votes come from.

Kids are still in schools and it’s June which means few holidaymakers but as this is Brittany expect plenty of people by the road today. The Tour can’t visit every year but it tries. If you visit you’ll find races galore every weekend and while the roads lack the drama of the Alps or Pyrenees you’ll never wait long to meet a local out on the roads.

What a great read! I have been an avid reader of INRNG since the beginning and this is one of my favourites. The insight you bring is unparalleled.

Very interesting, yes +1.

Just as a thought, since Breton riders are so well represented amongst their country’s riders, does this partly account for the long wait France has had for a TdF winner?

Brittany perhaps strikes you as natural Classics-type rider terrain, though past GC winners belies this, yet that was another age.

But, on first reflection, you’d think a French GC winner would come from / near the mountainous regions?

Remember plenty of Tour winners have come from the Netherlands, Filippo Ganna grew up with very few flat roads around. Local terrain can play a part but French riders tend to move around for the U23 ranks, if they can climb they might end up in a squad that has a more mountainous race programme, much more so than many Dutch or Belgian riders get.

There’s a perfectly reasonable theory that puts the centre of Celtic Europe at Lands End in Cornwall, as the centre of a giant compass tracing a circle through Ireland, Wales and Bretagne, and my own homeland, all linked by sea in pre-road times. But mainly it’s intense boredom that drives rural wannabes. Some of them are cyclists. Still, a Yorkshire sized Cornwall- that’s hell or heaven or both… (and I know both)

Paris-Brest-Paris still exists of course as one of the flagship events of Audax – something many amateur cyclotourists hope to be able to ride one day. Some of us know how far out of reach it is!

Brilliant article as ever. July is a great month as Inrng is the way to start every day 🙂

A few years ago I went to a post tour criterium in Brittany. It was a wonderful night. Huge crowds on a hilly rural circuit, the racers put on a show, there was plenty of beer, a retro bike and jersey exhibition. About as good as it gets as a cycling spectator.

Wonderful read during the less intense middle section of stage one, thank you.

Interestingly, the historical capital of the Duchy of Brittany was Nantes, which is in the modern Pays de la Loire region, presumably because including all of historic Brittany would have made for uneven regions economically and politically? Either way, what I’m getting at is what we think of as Brittany is still a bit of a modern construct. I’d be interested to know whether Nantes feels particularly Breton at all, if above knows the place.

Quite a can of worms you just opened there! 🙂

On the topic of the historical capital, it’s a bit tricky. Brittany never had an established capital the way most states had in the Middle-Ages, the court moved around a lot, mostly to Vannes, Rennes and Nantes, but to many other towns as well. Still now, Brittany has many middle-sized towns and is one of the most decentralized regions in France.

On the topic of Nantes, it’s been a debate, pretty much since inception (1958 for administrative regions) – numerous polls, not always using decent methodology, and of course a few demonstrations (this is France, after all). Most people in Loire-Atlantique (the departement that includes Nantes and the Pays de Retz) seem to be mostly in favor of joining Brittany. Most Bretons want it too, but less so in Finistere (Western Brittany) as they are afraid that the region would be too centered around the Eastern part, along the Rennes-Nantes axis. Regions get a big say in economic development projects, infrastructure, etc. so it’s an important topic.

That said, administrative regions aren’t really correlated to historical regions/provinces in France, at least not anymore. In 2015, there was a push for regions to merge, and France moved from 22 regions to 13. That move had some small impact on pro cycling, think of the Criterium du Dauphine (sponsored by the Rhone-Alpes region) visiting Auvergne more and more – because Auvergne merged with Rhone-Alpes. A few races were renamed, too (the ‘Route d’Occitanie’ or ‘A travers les Hauts-de-France’ are named after the new administrative regions). Many people expected Brittany to merge with the Pays-de-la-Loire, it was seen as a natural move, the leaders even were from the same political party – but it didn’t happen. Go figure.

That’s an interesting turn of events – thanks for adding colour!

Brittany is not a modern construct, even if the boarders were a little bit floating sometimes. But they always had a strong identity of the faraway land of fishermen and wreckers where you could hardly find someone speaking french until the beginning of the 20th century. As for Nantes, it was really Brittany until French revolution, who wanted to break the old french provinces. There has been a region reform not so long ago, and some people wanted Nantes back in Brittany ; it hasn’t been done, mainly for economic reasons.

Linguistically, too , Brittany has a second regional language, Gallo, which exists in the east of the region. Not being distinct from standard French and, possibly because it doesn’t fit neatly within regional borders, it doesn’t seem to have the same cultural importance.

Just to clarify my own post above, I meant that the language of Gallo is not distinct from standard French in the same way that Breton is. Breton, obviously, has different linguistic roots, while Gallo has it’s roots in the Romance languages, in the same way that standard French does.

Wonderful region, I remember the leg breaking roads with fondness.

I take the liberty to use a little bandwidth to compliment our host and the commentators. Brilliant, brilliant and informative!

+1

(Saving bandwidth too)

Outstanding post. Cycling historian Jean-Paul Ollivier has written several good books on Brittany, including most recently Les Champions Bretons du Tour de France.