Here’s the 2019 Tour de France guide. There’s a profile of every stage with a quick comment on the route. You’ll also find reference material on the race rules like time bonuses, the points scale for the green and polka-dot jersey, time cuts and plenty more.

Note: this is a blog post but there’s a permanent page, just look for the “Tour de France” link on the menu at the top of the page, or on the drop-down menu for mobile users.

Route Summary

Vertical in one word. While the yellow jersey and Eddy Merckx are the retrospective themes to this year’s race, the route offers a lot to look forward too. There’s plenty of climbing across the three weeks with an opening week that includes a hard summit finish at the Planche des Belles Filles and before that there are plenty of climbs to spice up the finish and thwart the sprinters. This is the anti-siesta Tour course, there will surely be some majestic slow moments but there are never more than two consecutive “sprint” stages. There’s only one time trial and it’s mid-race meaning no rider can count on taking back time in the final phase of the race, instead they’ll worry about losing if they crack in the succession of high altitude mountain passes that are the hallmark of the final Alpine stages.

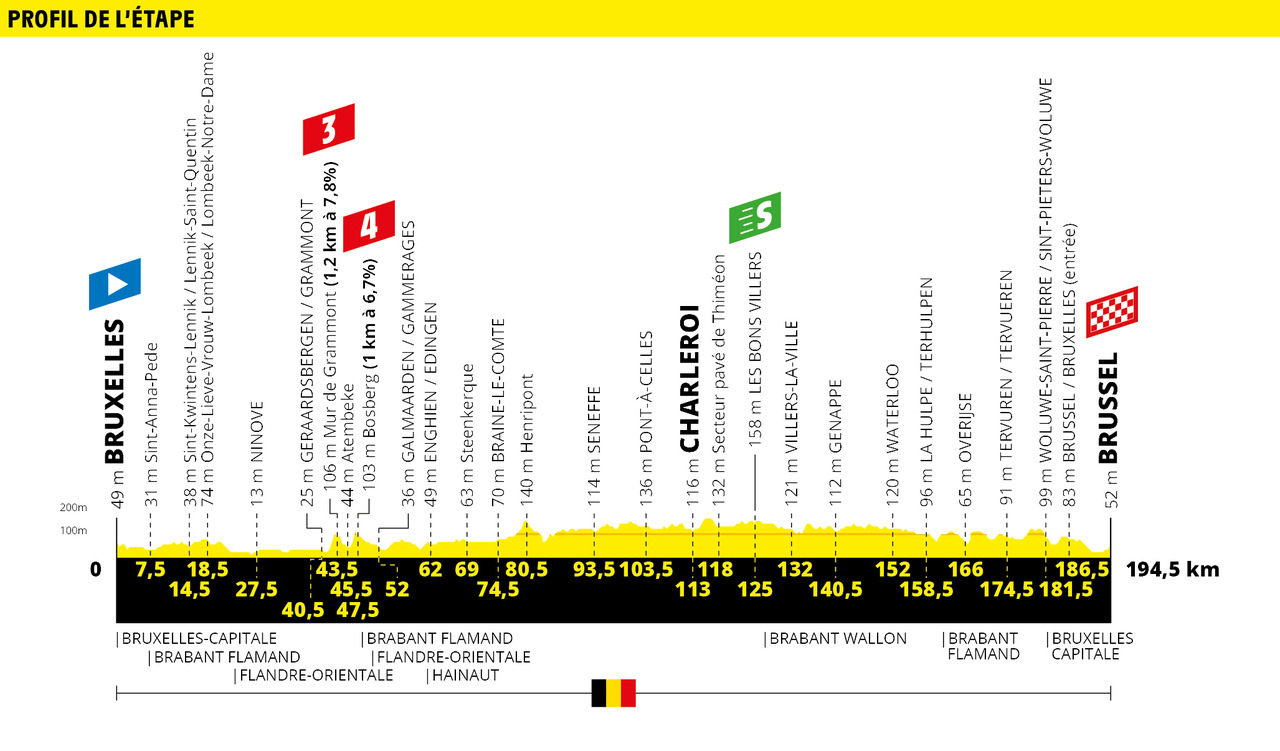

Stage 1 – Saturday 6 July

A celebration of Eddy Merckx including a trip through the suburbs where he grew up and then a passage across both the Flemish and French speaking parts of the country including the Muur in Geraardsbergen and the Bosberg, here counting for the mountains competition rather than shaping the race. Apparently the Tour was interested in a more Flandrien route but police advice on traffic closures meant things have to loop closer to Brussels. A sprint royale awaits among the best sprinters finally reunited in one race with the hallowed yellow jersey waiting for the winner

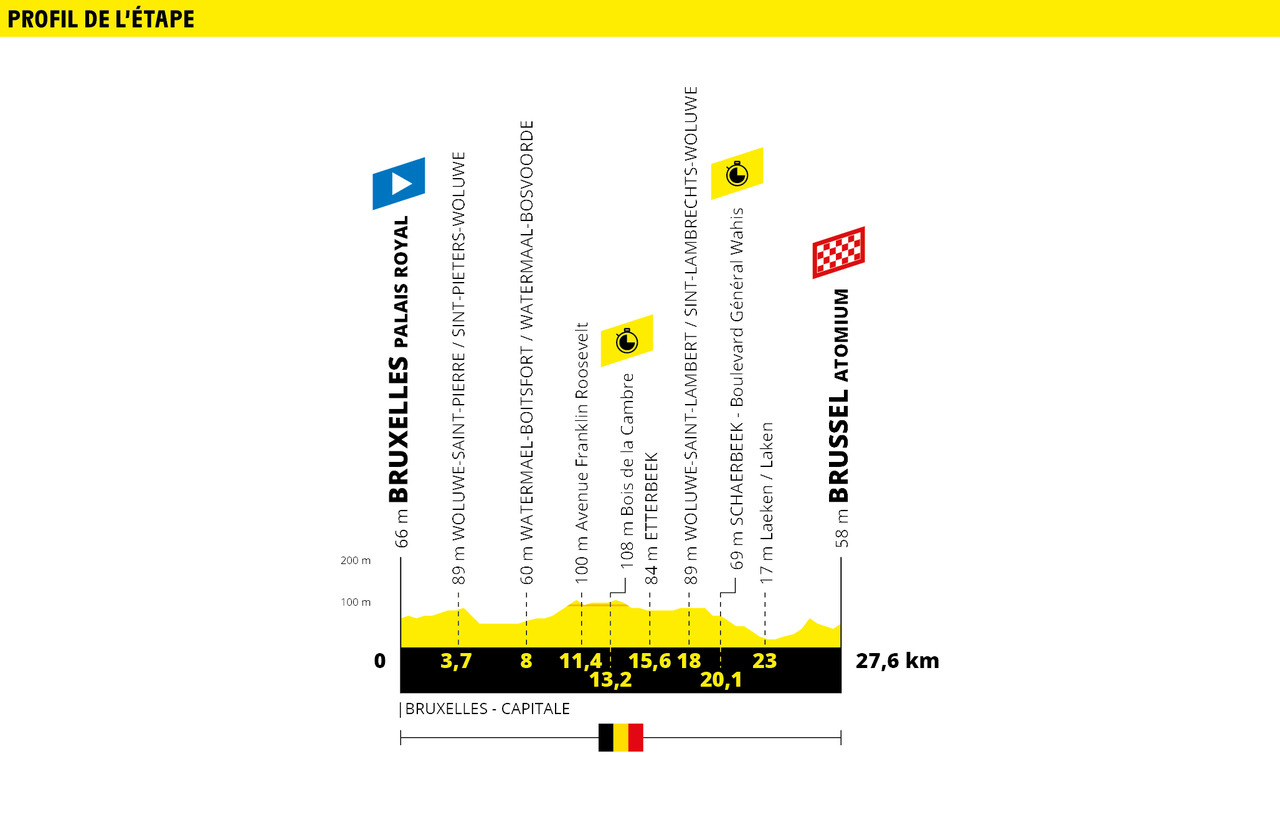

Stage 2 – Sunday 7 July

A team time trial that’s part tourist trail, part Merckxian pilgrimage. At 27.6km it’s a substantial distance to shape the general classification with a finish beside the iconic Atomium.

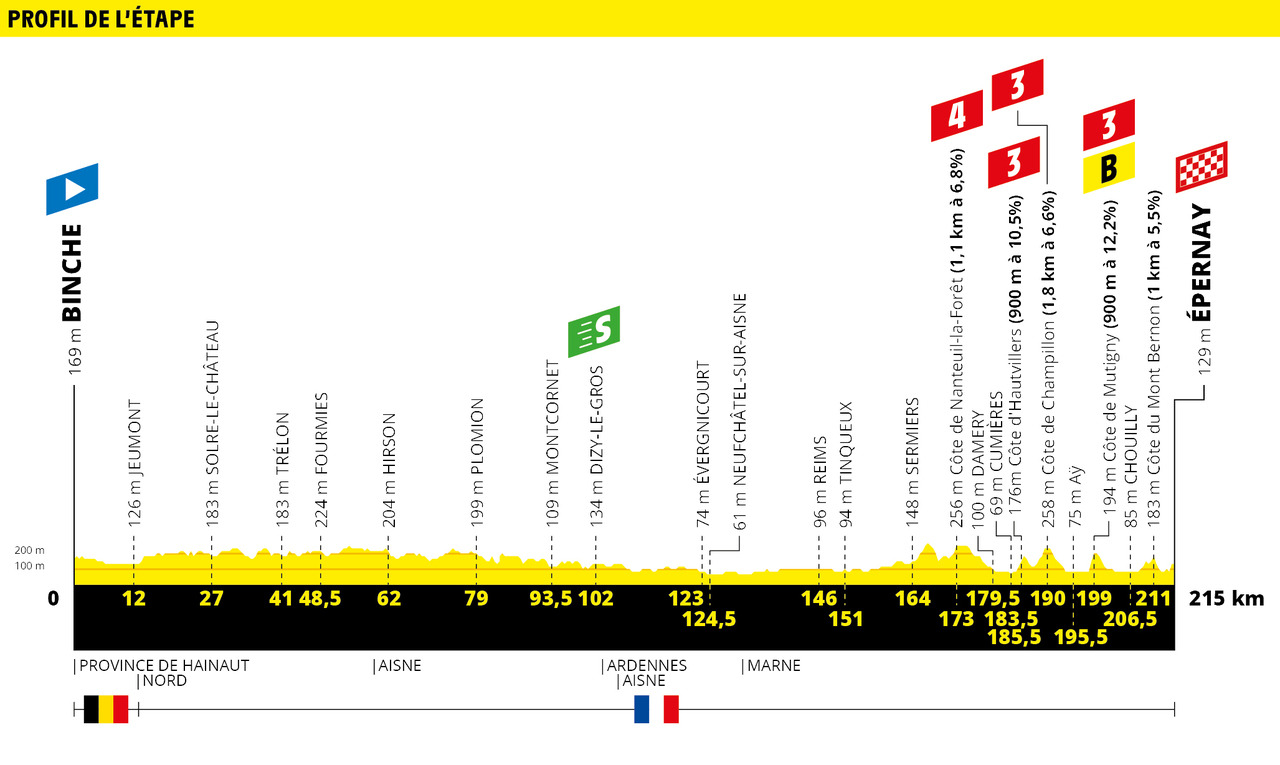

Stage 3 – Monday 8 July

215km from Binche to Epernay, from a town known for its brewery to another billed as the capital of champagne wine. The fizz comes in the finish with a succession of sharp climbs in the vineyards before an uphill finish.

215km from Binche to Epernay, from a town known for its brewery to another billed as the capital of champagne wine. The fizz comes in the finish with a succession of sharp climbs in the vineyards before an uphill finish.

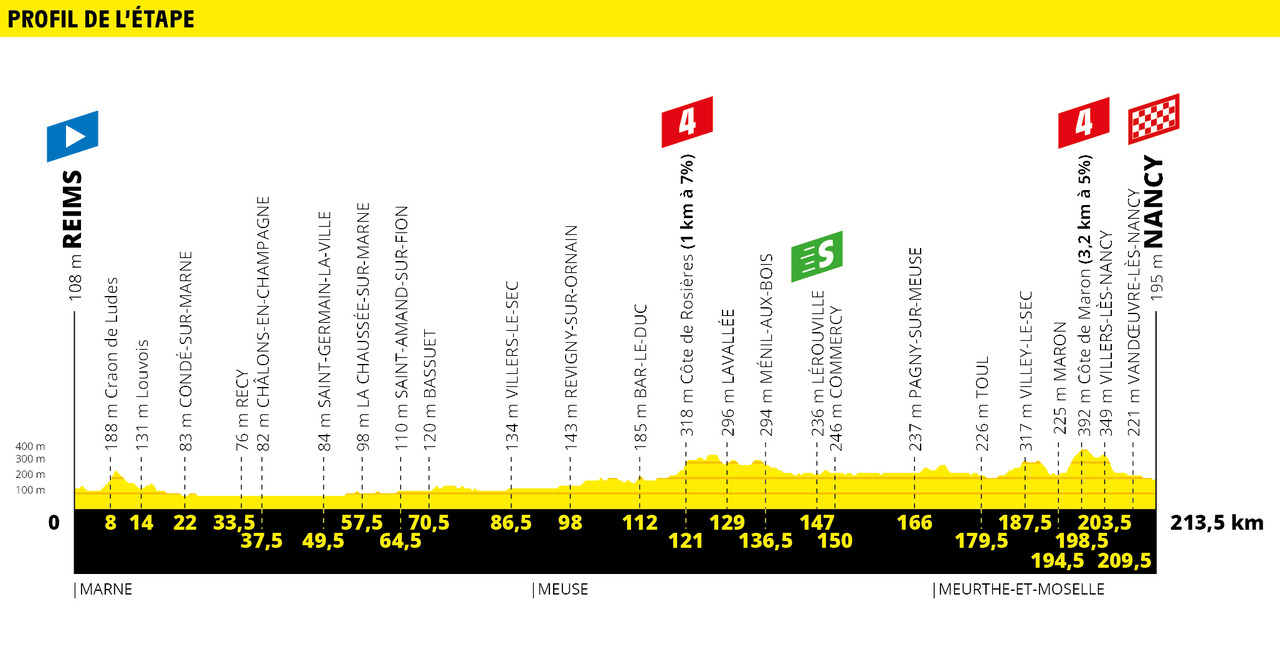

Stage 4 – Tuesday 9 July

A sprint stage but with a three kilometre climb thrown in with 15km to go, it’s a long drag up out the Moselle valley and for powerful riders rather than mountain goats but just the place for some teams to put the hurt on the heavyset sprinters.

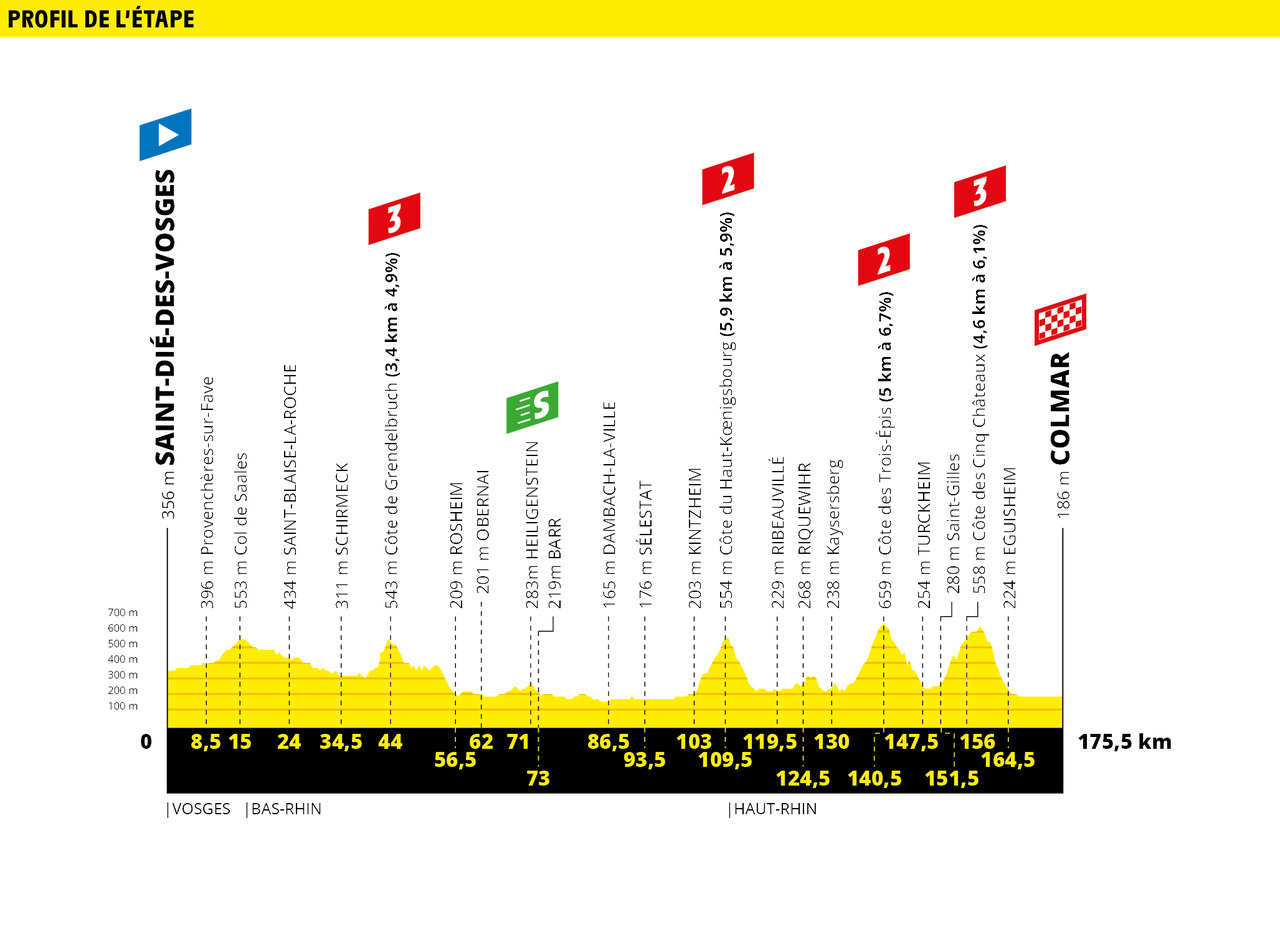

Stage 5 – Wednesday 10 July

A succession of climbs in the final half of the stage including the Trois-Epis, famous in motorsport and then the Cinq Chateaux, a sharp climb last tackled in the 2014 Tour.

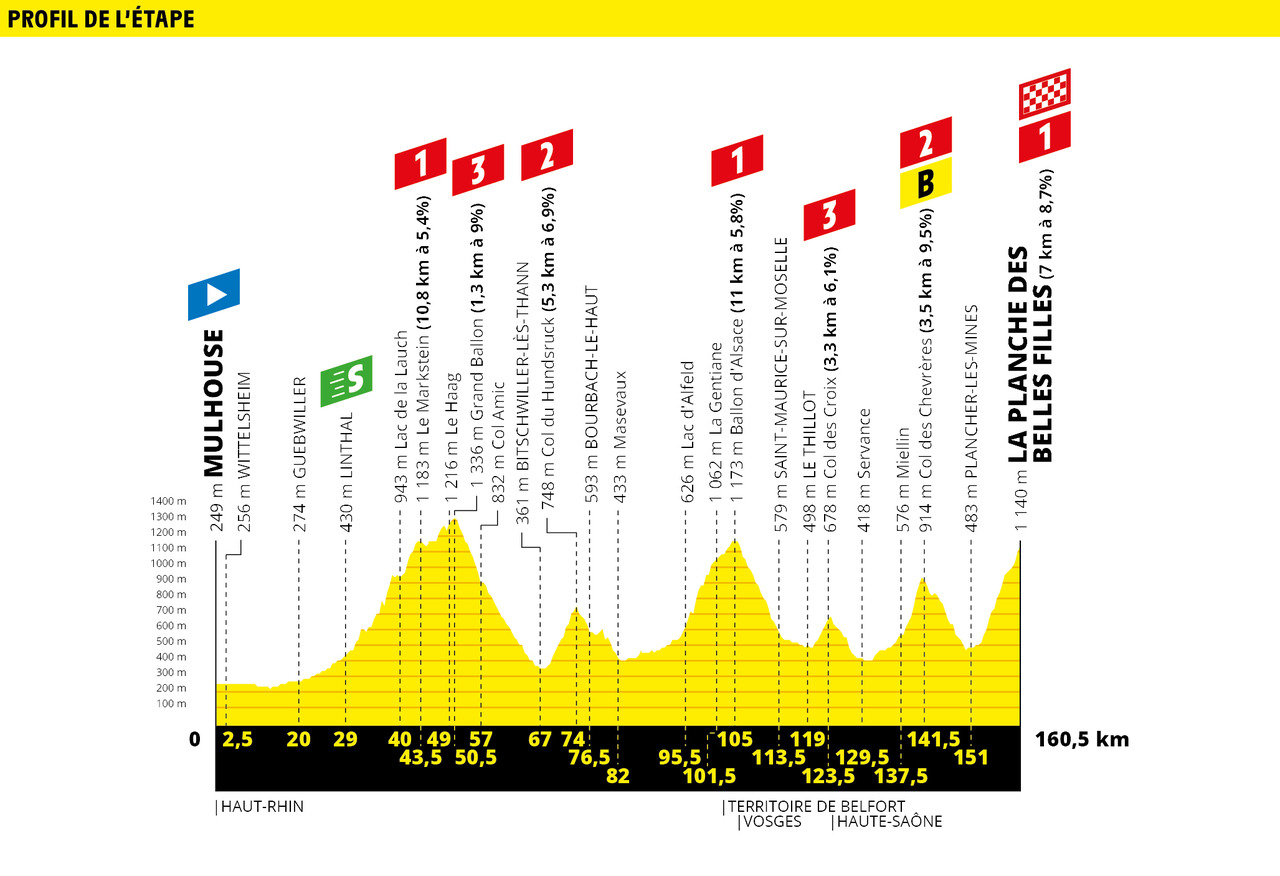

Stage 6 – Thursday 11 July

The first mountain stage and if the race doesn’t reach high altitude, it compensates with steep climbs in the finish, the Col de Chevrères is very hard towards the top and will shrink teams down before the Planche des Belles Filles, a tough summit finish made harder still by an extension to the road that makes the final part even steeper.

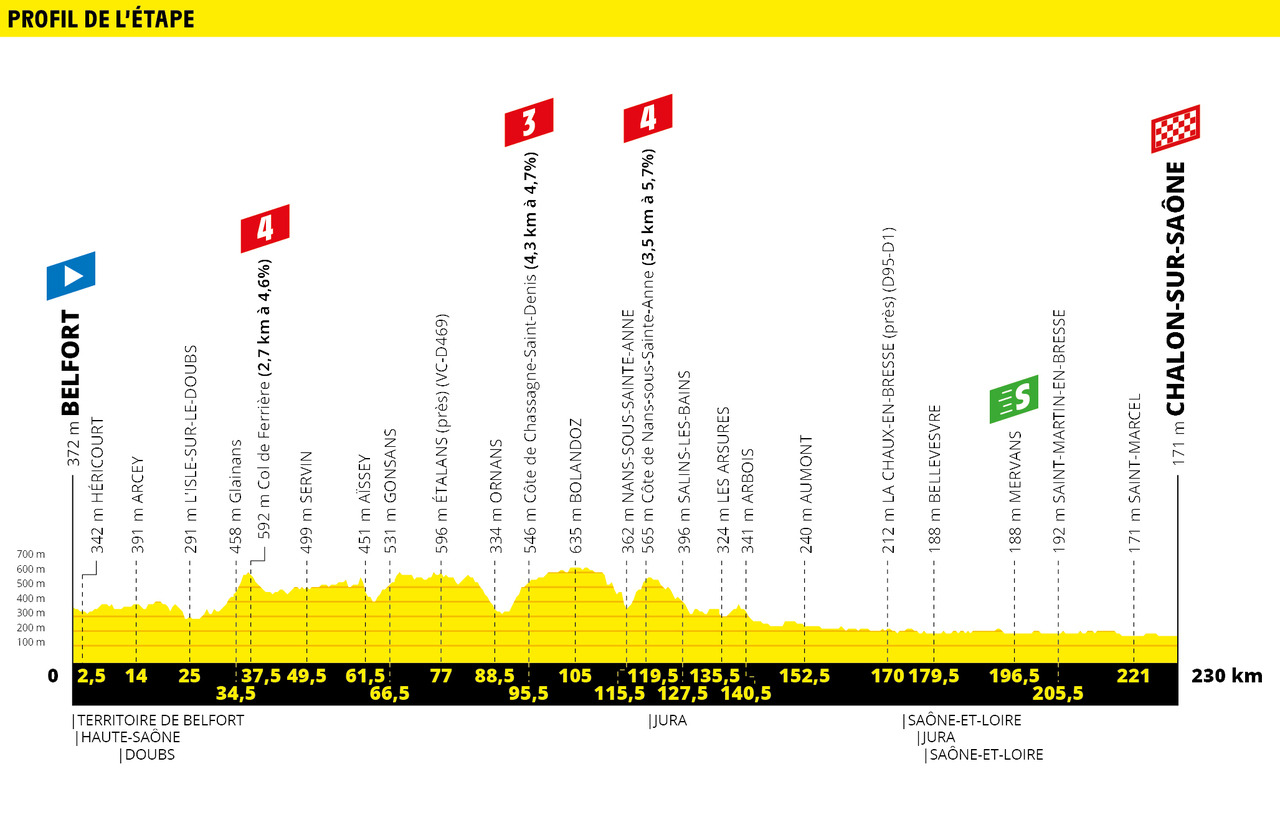

Stage 7 – Friday 12 July

The sprinters get their day with a finish in Chalon-sur-Saône, a regular haunt of Paris-Nice and the Dauphiné.

The sprinters get their day with a finish in Chalon-sur-Saône, a regular haunt of Paris-Nice and the Dauphiné.

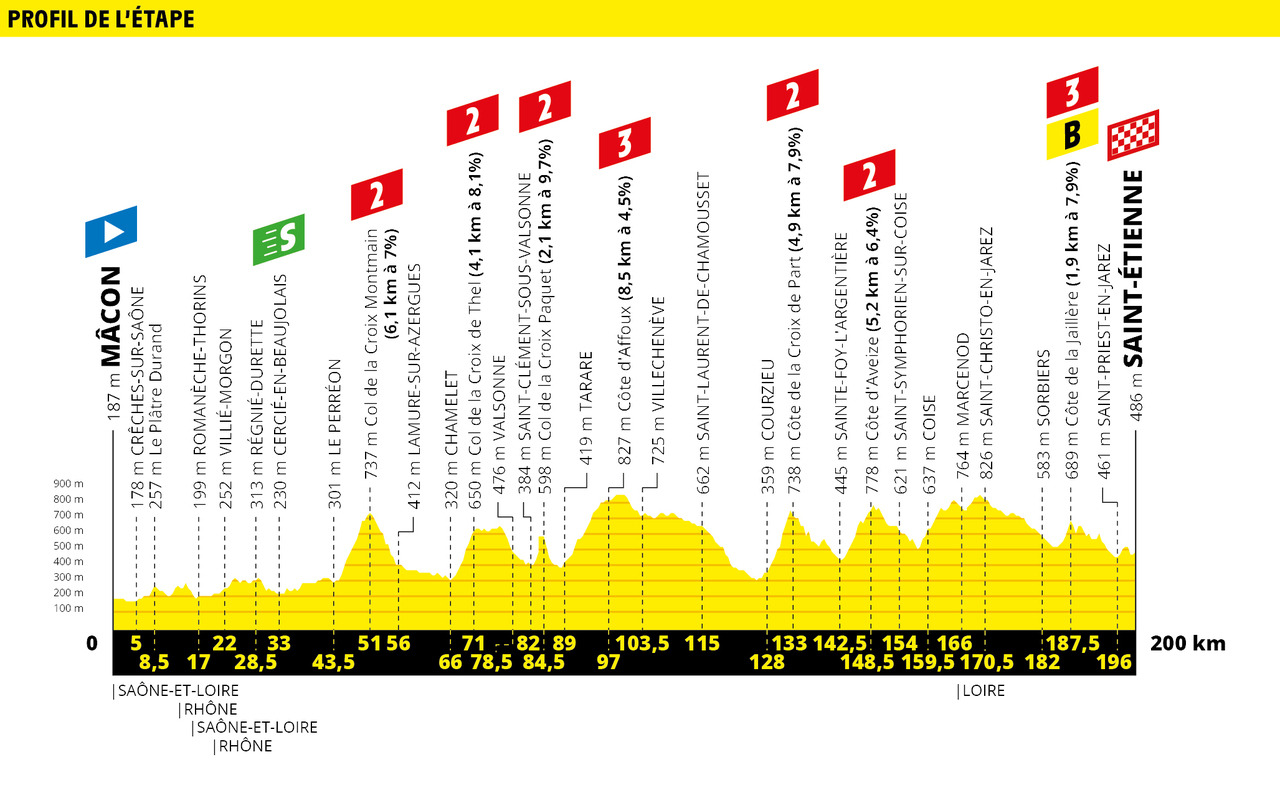

Stage 8 – Saturday 13 July

200km and rugged roads across the massif central. The start of the route reads like a wine menu before a succession of climbs that vary, some roll by in the big ring while others are awkward, all leading to the finish in the post-industrial city of Saint Etienne.

Stage 9 – Sunday 14 July

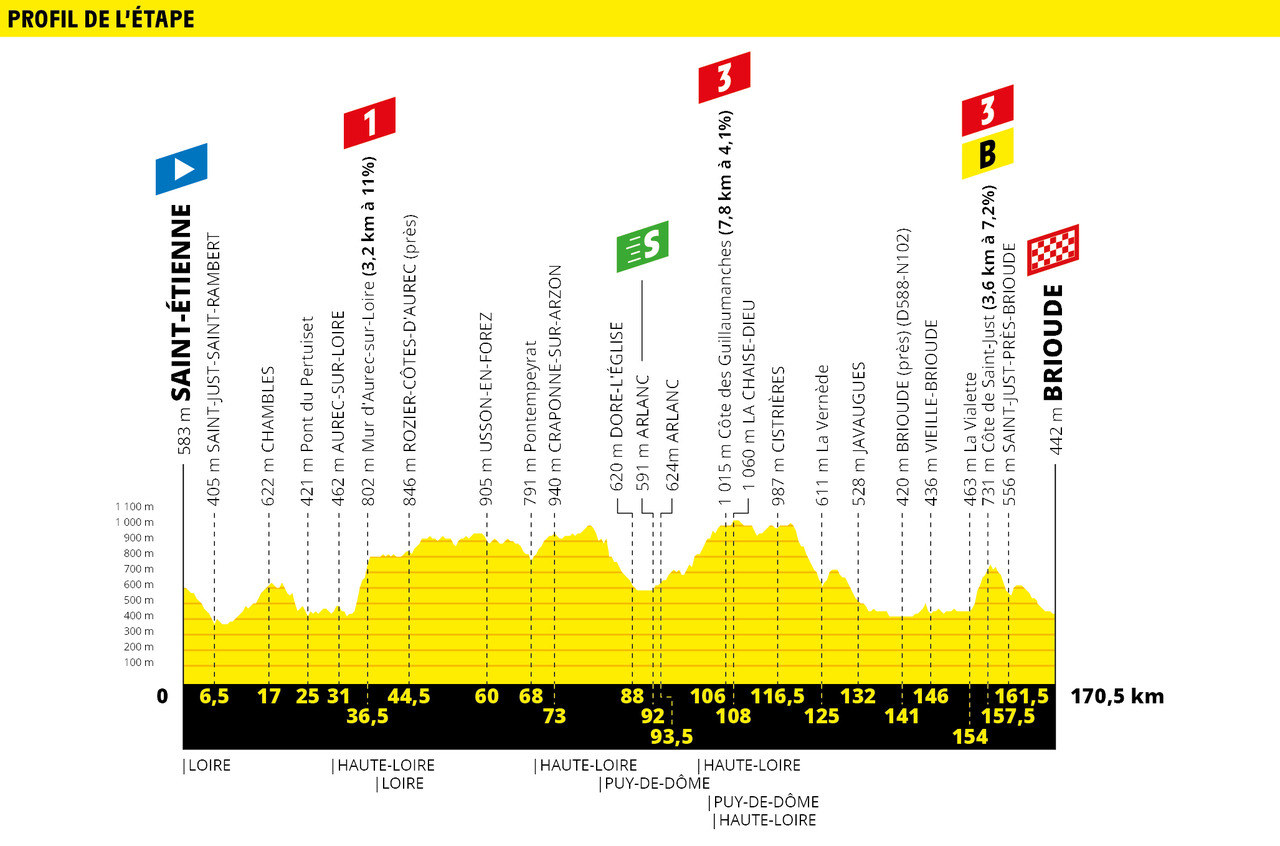

Bastille Day means a festive atmosphere and a hard stage awaits with the Mur d’Aurec ready to make the peloton taste breakfast again before a ride to Brioude, the town where Romain Bardet grew up and a surprisingly difficult climb in the finale before a quick descent to the finish.

Stage 10 – Monday 15 July

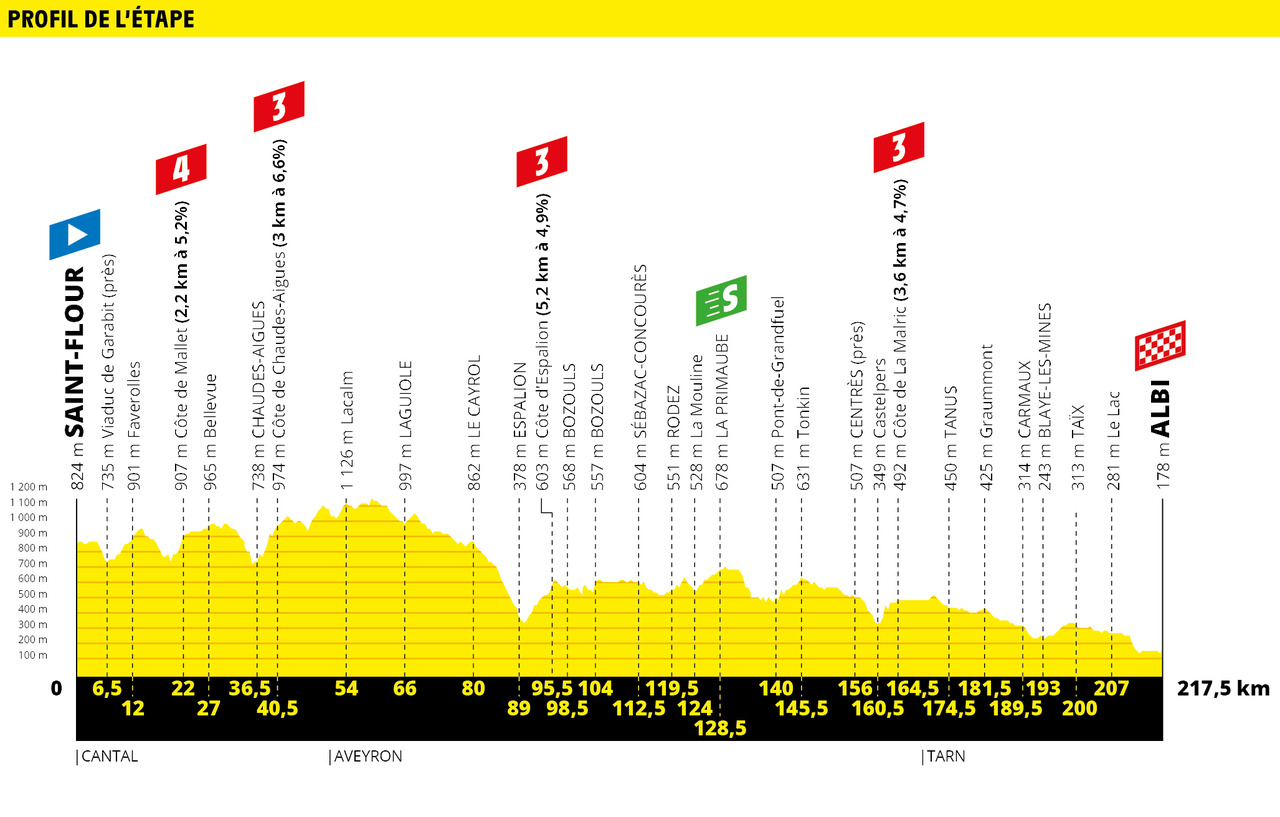

A scenic stage and a probable bunch sprint but with lumpy roads to blunt the legs before arriving in the red-brick city of Albi.

Stage 11 – Wednesday 17 July

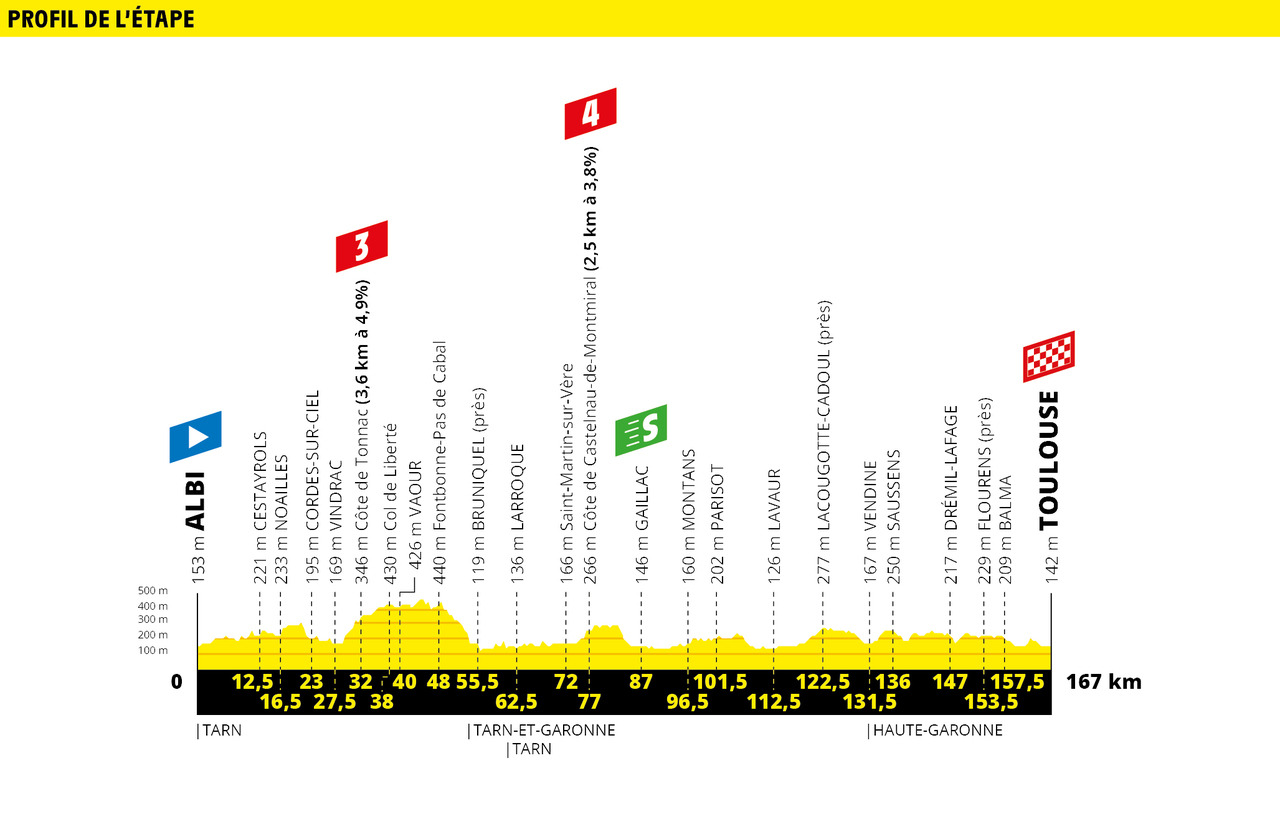

The stage for photos of the peloton passing fields of sunflowers, this is a ride across the Pays de Cocagne, a land of plenty, full of postcard scenes of French rural life before we find out which sprinter wins in Toulouse, as long as they can cope with the unannounced climb with 3km to go.

The stage for photos of the peloton passing fields of sunflowers, this is a ride across the Pays de Cocagne, a land of plenty, full of postcard scenes of French rural life before we find out which sprinter wins in Toulouse, as long as they can cope with the unannounced climb with 3km to go.

Stage 12 – Thursday 18 July

A start in Toulouse but from Le Mirail, a housing project built with utopian ideals only to end up as an urban ghetto, it’s a move by the Tour de France to show it can visit all of France. There’s a long procession south to the Pyrenees, and the Peyresourde comes first, a long highway of a climb, before a fast descent and then the sharp Hourquette d’Ancizan. There’s 40km to the finish which sounds a long way to go but it won’t take long.

Stage 13 – Friday 19 July

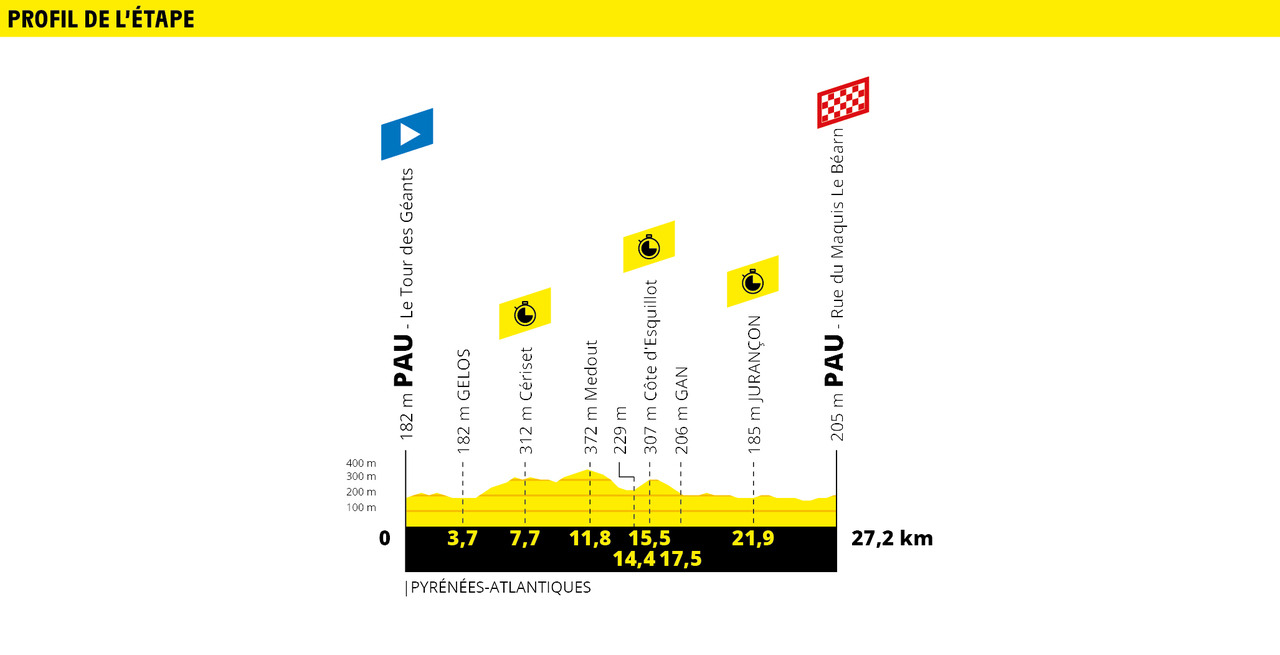

The only individual time trial of the race, a 27.2km course across lumpy roads with several short climbs.

The only individual time trial of the race, a 27.2km course across lumpy roads with several short climbs.

Stage 14 – Saturday 20 July

A Tour de France classic, the Soulor and Tourmalet but this time served up as a reduction with just 117.5km.

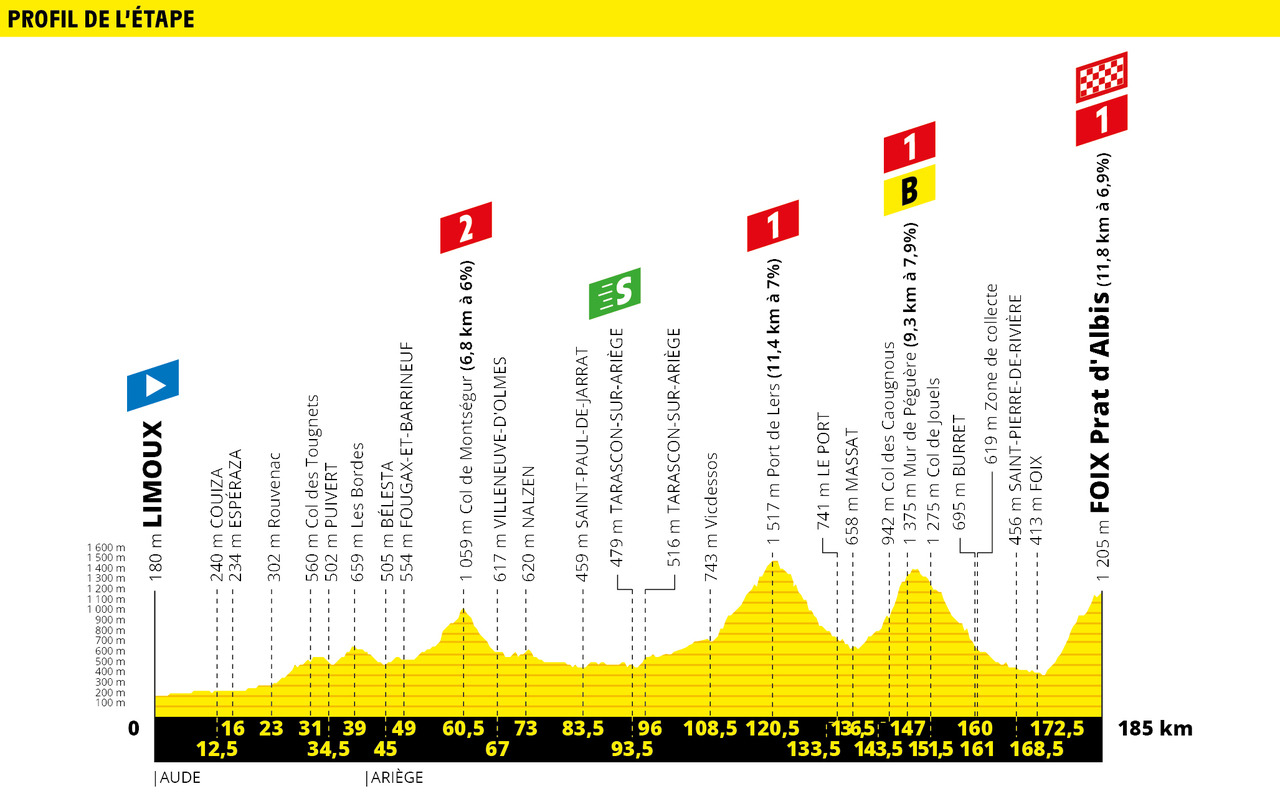

Stage 15 – Sunday 21 July

A scenic ride through quiet countryside and the final two hours are packed with hard climbs including the Mur de Péguère before a “new” summit finish, the Prat d’Albis sits above Foix and includes some double-digit gradients. In case you’re wondering a prat is a large field or a plateau high up.

Stage 16 – Tuesday 23 July

A reward for the sprinters with a loop around the Roman city of Nîmes but tricky if the mistral wind is blowing.

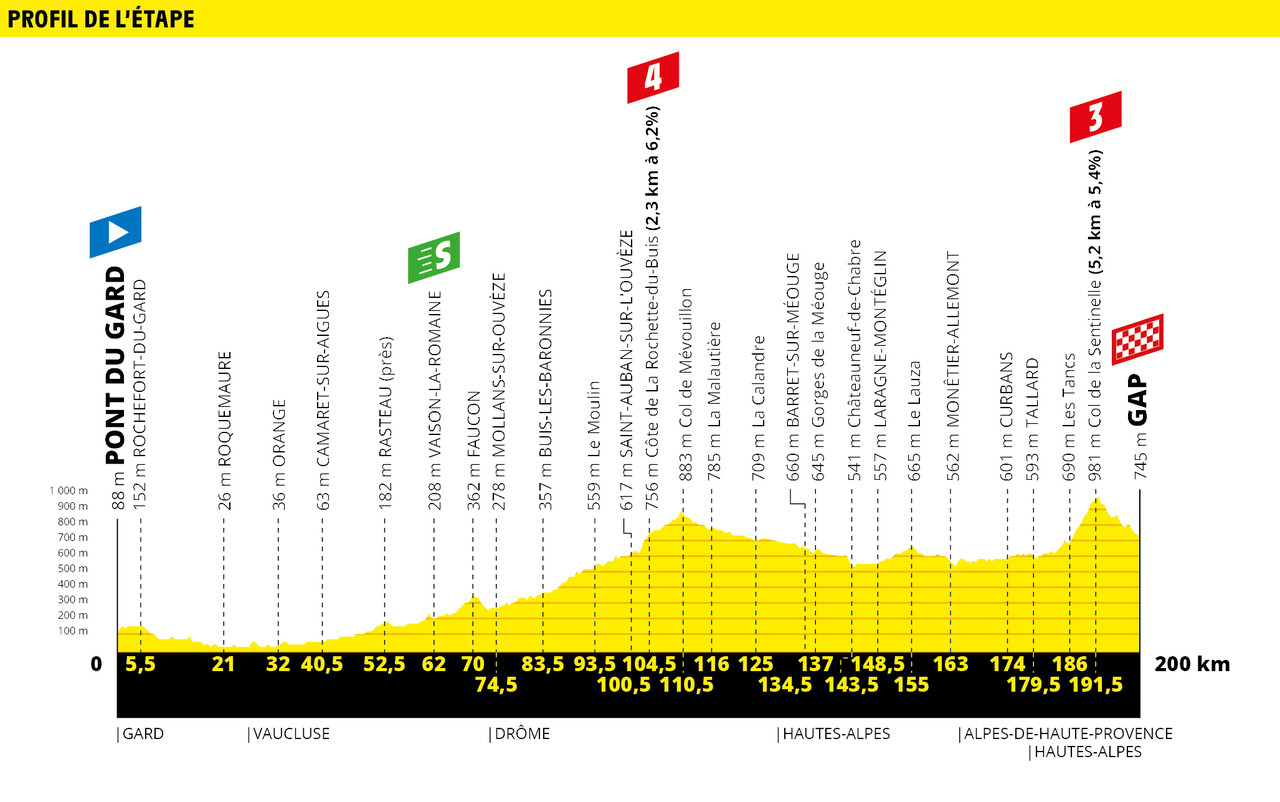

Stage 17 – Wednesday 24 July

The race rides into the Alps and tackles the Col de la Sentinelle which is 5km at 5% but with a 10% section to scale before a fast descent into Gap (but not “that” fast descent, this isn’t the road from La Rochette). It’s a big day for a breakaway and half the peloton will have their eyes on getting in the move here.

The race rides into the Alps and tackles the Col de la Sentinelle which is 5km at 5% but with a 10% section to scale before a fast descent into Gap (but not “that” fast descent, this isn’t the road from La Rochette). It’s a big day for a breakaway and half the peloton will have their eyes on getting in the move here.

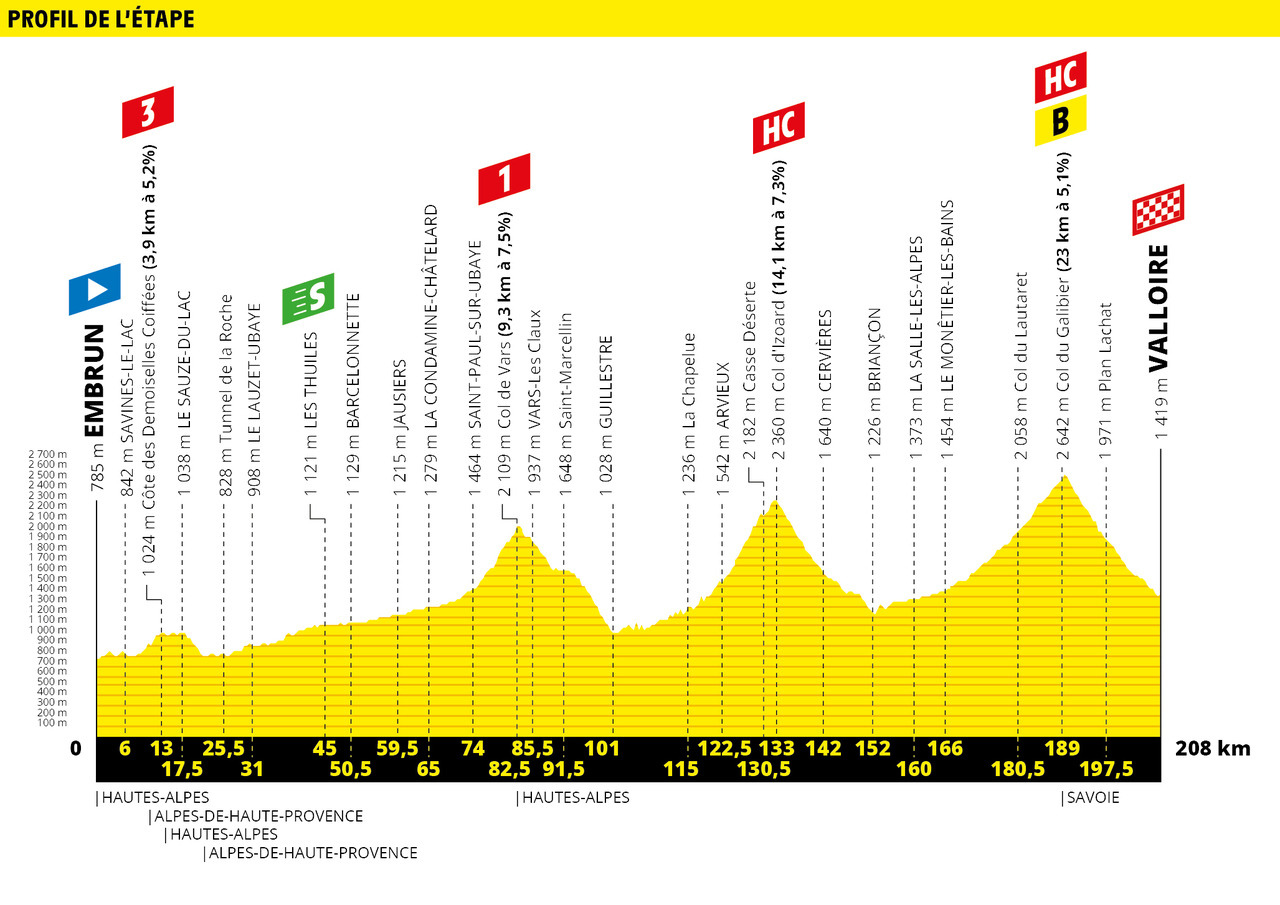

Stage 18 – Thursday 25 July

A mountain marathon, 208km with the Vars-Izoard and Galibier with such a fast descent that the Galibier is a virtual summit finish.

A mountain marathon, 208km with the Vars-Izoard and Galibier with such a fast descent that the Galibier is a virtual summit finish.

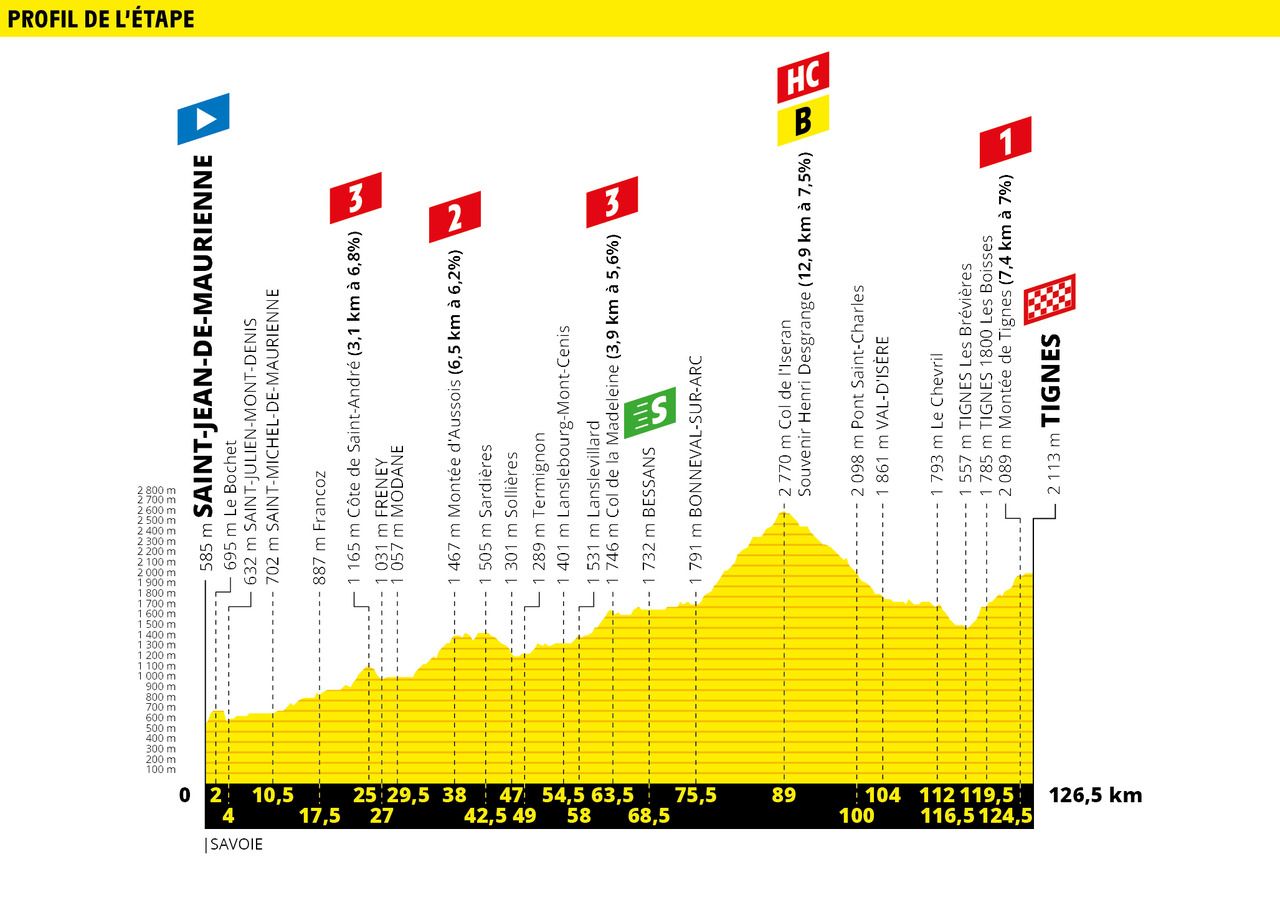

Stage 19 – Friday 26 July

A short stage with the giant Col de l’Iseran, Europe’s highest mountain pass but tackled from its shorter side before a more gentle climb into the ski resort of Tignes.

A short stage with the giant Col de l’Iseran, Europe’s highest mountain pass but tackled from its shorter side before a more gentle climb into the ski resort of Tignes.

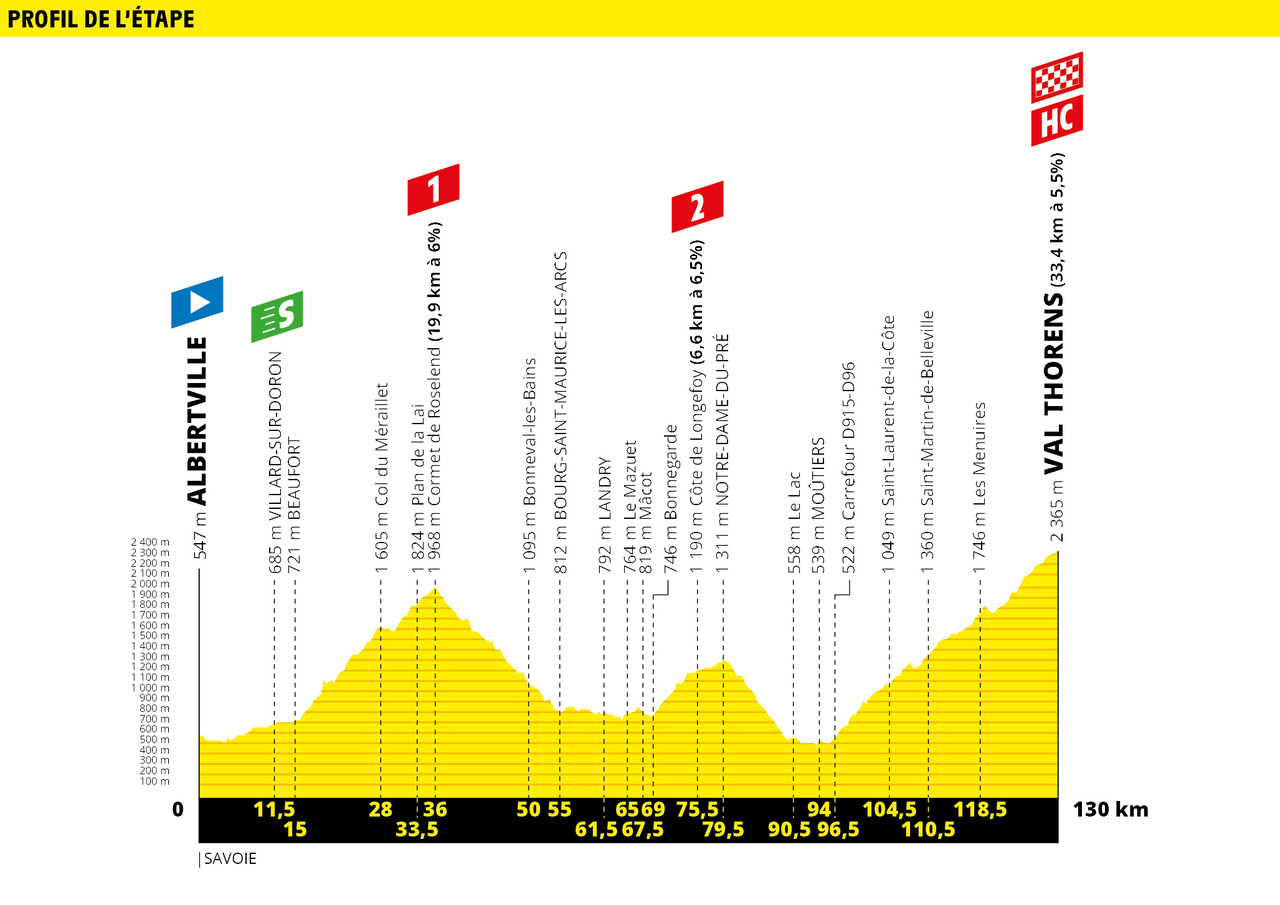

Stage 20 – Saturday 27 July

The final mountain stage and a hard day with 4,500m of vertical gain in just 130km.

The final mountain stage and a hard day with 4,500m of vertical gain in just 130km.

Stage 21 – Sunday 28 July

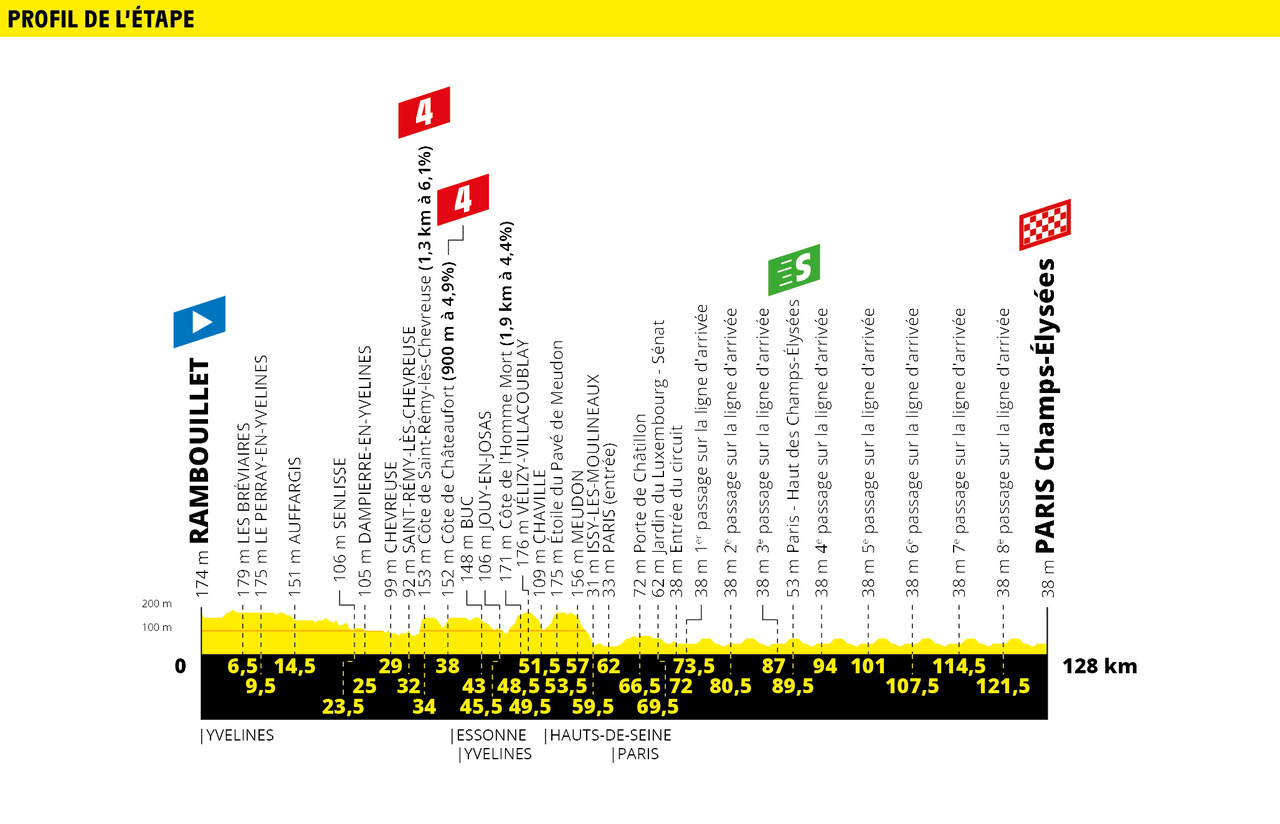

A 60km parade that mutates into a 60km criterium and the evening finish on the Champs Elysées.

The Jerseys

Yellow: the most famous one, the maillot jaune, it is awarded to the rider with the shortest overall time for all the stages added together, the rider who has covered the course faster than anyone else. First awarded in 1919, it is yellow because the race was organised by the newspaper L’Auto which was printed on yellow paper. Today it is sponsored by LCL, a bank. There are time bonuses of 10-6-4 seconds for the finish of each stage except the time trials.

There are also 8-5-2 seconds at the bonus sprints marked “B” on the profiles above on Stages 3,6,8,9,12,15,18 and 19s, typically atop various mountain passes.

Green: the points jersey, which tends to reward the sprinters. Points are awarded at the finish line and at one intermediate point in the stage and the rider with the most points wears the jersey. It is sponsored by Skoda, a car manufacturer

- Flat stages (Stages 1,4,7,11, 16, 17, 21) 50-30-20-18-16-14-12-10-8-7-6-5-4-3 and 2 points for the first 15 riders

- Hilly finish / Medium mountain stages (Stages 3,5,8,9,10,12): 30-25-22-19-17-15-13-11-9-7-6- 5-4-3-2 points

- Mountain Stages + individual TT (Stages 6,13,14,15,18,19,20) : 20-17-15-13-11- 10-9-8-7-6-5-4-3-2-1 points

- Intermediate sprints: 20-17-15-13-11-10-9-8-7-6-5-4-3-2-1 points

Polka dot: also known as the “King of the Mountains” jersey, points are awarded at the top of categorised climbs and mountain passes, with these graded from the easier 4th category to the hors catégorie climbs which are so hard they are off the scale. In reality these gradings are subjective. Again the rider with the most points wears the jersey. It is sponsored by Leclerc, a supermarket.

- Hors Catégorie above 2,000m passes (5 in total, namely the Tourmalet, Izoard, Galibier, Iseran and Val Thorens): 40-30-24-20-16-12-8-4 points respectively for first eight riders

- Category 1 climbs (13 in total): 10-8-6-4-2-1 points

- Category 2 (12): 5-3-2-1 points

- Category 3 (21): 2-1 points

- Category 4 (14): 1 point

Normally it’s 20-15-12-10-8-6-4-2 points for HC climbs but this year all HC climbs above 2,000m, ie all of them in the race, get double points.

White: for the best young rider, this is awarded on the same basis as the yellow jersey, except the rider must be born after 1 January 1994, ie aged 25 or under. It is sponsored by Krys, a retail chain of opticians.

Obviously a rider can’t wear two jerseys at once, they’d get too hot. So if a rider leads several classifications, they take the most prestigious jersey for themselves and the number two ranked rider in the other competition gets to wear the other jersey. For example if a rider has both the yellow jersey and the mountains jersey they’ll wear yellow while whoever is second in the mountains jersey will sport the polka dot jersey. If a rider has all the jerseys the priority yellow, green, polka dot then white.

There’s also a daily “most combative” prize awarded every day to the rider who has attacked the most or tried the hardest. It is a subjective prize and awarded by a jury. The rider gets to stand on the podium after the stage and wear a red race number the next day. There will be a final Supercombatif prize with involvement from the jury and social media. It is sponsored by Antargaz, a bottled gas company.

Time Cuts

The time cut depends on the stage in question and the scale is the same as last year, sprinters beware. Look up the stage and its coefficient on the table above and then match it to the listings below.

Timekeeping

Normally a one second gap on the finish line is needed to separate groups in a finish but for Stages 1,4,7,10,11,16 and 21, expected sprint stages, three seconds is needed for a split in the field. The three kilometre rule doesn’t apply on Stages 2,6,13,14,15,19 and 20.

The unmissable stages

This is the Tour de France and there’s always something to watch but there are some stages that matter more than others. If you need to plan ahead, here are some suggestions for the stages to watch.

- Stage 1: the sprint finish is the interest, a sprint royale among the top names

- Stage 3: the hilly finish

- Stage 5: the even more hilly finish

- Stage 6: the Col de Chevrères and Planche des Belles Filles, the first summit finish

- Stage 12: the first day in the Pyrenees

- Stage 14: 117km ending atop the the Tourmalet

- Stage 16: the Prat d’Albis summit finish

- Stages 18, 19 and 20: three consecutive days of high mountains

TV Guide

Every stage will be shown live from start to finish. Think of it like the radio, something to have in the background or in a more modern way you can tune in from time to time via your phone in case there’s early action. The daily finish time varies between 5.00pm-5.55pm CEST each day.

The race will be broadcast on a variety of channels around the world. There is no free stream on the internet but you will find a feast of legitimate feeds from local broadcasters and international sources like Eurosport.

The Prizes

- Each day on a normal stage there’s €11,000 for the winner, €5,500 for second place and a decreasing scale down to a modest €300 for 20th place

- For the final overall classification in Paris, first place brings in €500,000 and the Sèvres porcelain “omnisports trophy”, awarded “in the name of the Presidency of the French Republic”. The full breakdown is €500,000 for first place, €200,000 for second place, €100,000 for third place and then €70,000, €50,000, €23,000, €11,500, €7,600, €4,500, €3,800, €3,000, €2,700, €2,500, €2,100, €2,000 €1,500, €1,300, €1,200 and €1,100 for 19th place. €1000 for 20th-160th overall

There are other pots of money available in the race:

- €500 a day to whoever wears the yellow jersey, €300 for the other jersey holders

- €25,000 for the final winner of the green and polka dot jerseys

- €20,000 for the final winner of the white jersey

- There’s also money for the first three in the intermediate sprint each day: €1,500, €1000 and €500

- The climbs have cash too with the first three over an HC climb earning €800, €450 and €300 and lesser sums for lesser climbs

- The highest point in the race sees a prize when on Stage 19 the Henri Desgrange prize is awarded at the top of the Col d’Iseran and is worth €5,000

- The Souvenir Jacques Goddet is awarded to the first across the Tourmalet and is worth €5,000

- The “most combative” prize is awarded and worth €2,000 each day, the “Super combative” prize is awarded in Paris and the winner collects €20,000.

- There’s also a team prize with €2,800 awarded each day to the leading team on the overall, calculated based on each team’s best three riders per day, €50,000 for the final winners in Paris. Note the team prize is calculated by adding the time of the best three riders each day rather than the best three on GC. For example if a team has riders A, B and C make the winning break one day then their times for the stage are taken and added together. If riders X, Y and Z on the same team go up the road the next day, their times are taken. So it’s the times of a team’s best three riders each day as opposed to the best three riders overall.

The total prize pot is €2,291,700, meagre for an event of this scale but remember that unlike, say tennis or golf, pro cyclists are salaried and prize money instead is incidental and the money is shared around the team (as well as levied and taxed) rather than pocketed by the winner, it’s quite possible the actual prize winner actually collects 5-10% of the headline sum. In addition, every team that starts gets paid €51,243 to cover expenses. And should a squad make it to Paris with six or more riders they stand to collect an additional €1,600 bonus for each rider.

Thanks, as always a great summary, looking forward to your in-depth previews, seems like the short stage becomes even more popular? I think it’s Ineos’s tour to lose, definitely the strongest team, two cards to play (Bernal) and the defending champ (Thomas).

Small typo – stage one ‘group’ should be grew

Awesome summary.

This year is going to be a great edition.

This route looks great!

It feels like in most recent years the TdF has designed a route to entice ‘set piece’ action, especially with lots of flat sprint stages in the first 7-10 days. But this route looks like it could create lots of unpredictable racing, or at least some battles between classics-style riders…Can’t wait!

I strongly suspect that even with Froome out this TdF like so many others this decade will be dominated by Ineos’ vastly superior domestiques with Thomas/Bernal pinging off the end of the train in the last few km of mountain stages.

One cannot blame Ineos for following this highly successful strategy, but it does make for very dull racing.

Furthermore, we now hear that Ineos plan to do this for all grand tours, buying up yet more talented GT contenders.

Some might say that this post isn’t relevant to a TdF guide, but it doesn’t matter what you do to the route the racing will remain dominated by Ineos’ train as long as they have a team that is so much better than all the others.

The only possible solution to this is a budget cap. Unlike, say, football, there is a very limited amount of money in cycling: in football, you can have many very wealthy teams. You can’t have that in cycling. That is why it is so easy for one team to dominate GTs (they’re much more easy to control than one-day races – yes, DQS have won an awful lot of one-day races, but their dominance over the last decade is nowhere near what Ineos has achieved in GTs).

People will say that other teams should ‘step up’ and equal Ineos’ funds, but this simply isn’t possible – the money isn’t, and never will be, there. Such an economic arms race would also be unsustainable and would crush the smaller teams. And yes there have always been dominant teams, but not to this extent – and certainly not to the extent of Ineos’ plans – and not to such a detriment to entertainment when it comes to GTs

Some will also say that having a salary cap is punishing excellence, but it does not punish individual excellence – it would actually mean riders who are currently domestiques could be team leaders. If you move away from the idea that money always improves things you can see that in sporting terms, money being the over-arching factor is not good for GT racing.

Many claim that teams such as Katusha-Alpecin spend almost as much as Ineos do, but this does not stand up to the slightest scrutiny: you only have to look at these two teams’ respective rosters… unless you believe that Katusha-Alpecin are paying riders of the calibre of their domestiques as much or almost as much as Ineos are paying theirs (or K-A are gifting Zakarin about 10 million Euros per annum).

It’s been said that a salary cap cannot work, but it does in other sports and if the will is there it would be relatively easy to do. For example, people have said that this might flout some international laws, but you could make all teams register in Switzerland (I’m sure their accountants would be delighted) and all teams would have to adhere to the same laws. And yes teams would look for ways around it, but it would certainly work to an extent: Ineos, for instance, could not possibly continue with their current roster without everyone knowing that they were not adhering to the rules.

Finally, some might suggest that this is all just anti-Ineos bias. This is, however, a ludicrously facile claim. Do they honestly believe that if FDJ or Jumbo-Visma were dominating GTs to this extent the neutral fan would be happy with the tedious state of GT racing? (Also, from my own perspective, look at Froome’s Giro victory: there can’t have been a more exciting day of GC racing for years.)

This is purely about how to make GTs interesting again – I don’t care who wins. I haven’t seen an interesting GC contest at the TdF since Cadel Evans won. And the style of racing – watching a team process through an entire stage until the final few kilometres – cannot be exciting for anyone bar the most fervent fan of the team involved.

Sport is about entertainment and if Ineos’ GT plan comes to fruition, we face many years of dull GTs.

I definitely understand your reasons and also that there’s an issue at a with the TdF and some might say in the spring too with Deceuninck. Outside of that though it’s hardly a problem and Ineos’s inability to pick up the sort of results Bora have all season long shows that part of it is their decision to concentrate so much on the TdF. So how much your solution would impact is up for discussion. It might just mean Ineos worry even less about other races. Also, the problem is Salary Caps have their own issues. There’s not a season that goes by where there isn’t someone somewhere flouting the rules. Often not found out about till years later and this is in sports and leagues where everyone is being rewarded and paying taxes in the one country.

How do you propose the UCI will police issues like partners/wives/and in David Rebellin’s case, grandkids, receiving an income from a sponsor, for doing very little, in their home country? There are so many ways outside of the straightforward salary and bonuses to remunerate athletes. How do you stop a rider receiving a large sum for doing some commentary work for example. A sum that is in reality paid by a sponsor who both supports the team and advertises with the television company?

Let’s face it, if you believe that there are riders and/or coaches and/or teams that are involved in illegal drug use, expecting the same people to play by some type of fair play financial rules is the stuff of fairy tales. Especially when the ability to police it would be haphazard and piecemeal at the very best.

“and in David Rebellin’s case, grandkids”

Funny

“I strongly suspect that even with Froome out this TdF like so many others this decade will be dominated by Ineos’ vastly superior domestiques with Thomas/Bernal pinging off the end of the train in the last few km of mountain stages.”

Yawn

Have you not watched any racing this year?

Astana employing similar tactics and being succesful!

Movistar, since the introduction of Max Sciandri, have changed tactics and been far more aggressive!

It will be good to watch other teams taking the fight to Ineos…..

Excitement is in the eye of the Beholder…Thank goodness we all have different opinions on what makes a good race…..!!!

My comment was specifically about grand tours and what has happened in the last few years at the TdF. It wasn’t about other races.

Movistar were relatively dominant in this year’s Giro, but as in other years I expect this won’t happen once Ineos’ A team of superior domestiques turn up at the Tour. That’s why I think even though Ineos don’t necessarily have the best rider – this must be Porte’s and Quintana’s best chance of winning the Tour – they will still dominate how the race is ridden.

We’ll see….

“…I think even though Ineos don’t necessarily have the best rider…”

I think this is what makes this year a little different – Sky/Ineos have never won the Tour without Froome in the team. He’s always been the best or next best rider in the race, plus frighteningly consistent, and an experienced leader. That leaves potential for cracks that can be exploited by other teams.

Have to say that Bernal looked supreme at TdS, but we never saw him under pressure and I’m looking forward to seeing just how good the kid is.

In short, I think this year is far from an Ineos done deal and there are narratives and sub-narratives aplenty to keep things interesting along the way.

Good arguments against salary caps. In my opinion the only way to break the dominance of a money fueled powerhouse team like Ineos is to reduce the number of riders per team in the race and allow more teams in the Tdf. But I wouldn’t be surprised when a team like that would simply buy in an extra team.

Anonymous, you point out a lot of flaws with a budget cap: you’re right and I’m sure there are many more. It wouldn’t be perfect, but I think it would be better than what we have now – and particularly if Ineos do follow through with this apparent plan to do the same in all grand tours.

A budget cap would work to an extent. Plus, I can’t see anything else that would have such an equalising effect. Like someone else on here, I suspect that if you had teams with significantly lower numbers of riders you would end up with teams ‘mysteriously’ working together – and unlike financial shenanigans you’d never be able to prove that.

The tour hasn’t even started and you’re already complaining about it being boring!!?!

Sky hasn’t dominated GTs, only the TDF, and they’ve generally been pretty poor in one day races. They’ve chosen to put most of their eggs in the TDF basket and have reaped the rewards. I agree that they’re the favourites again this year, but it’s entirely possible that Thomas can’t find last year’s form and then Bernal crashes or runs out of steam. So I’m not sure there’s such a problem as you seem to think.

I get your point George, but 1 team having the 3 clear favorites before the race starts isn’t really parity. Especially as Poels could easily podium on a course like this too.

Whilst it has mainly been the TdF (I say ‘mainly’ as there have been quite a few P-N, Romandie, Dauphine and Suisse too that they scooped up in bland controlled fashion).

8 F1 races this year – Hamilton won 6, Bottas won 2 (both Mercedes). Mercedes on the way to doubling the points of the next best team already. Is anyone interested? Do we want TdF like this?

@Dan, as a comparison, take the Spring Classics campaign when DQS would regularly put out a team of 3 or more riders. There was one race (forget which) where Inrng gave their entire team 5 chainrings!

No one complains?

I think the difference is in the style of racing?

In the classics, by having such a strong team, Quickstep help to ‘open up’ the racing (making moves & counters, attacking from distance). Whereas, by the nature of Grand Tour racing, Ineos’ approach is to ‘close down’ the racing.

There’s also the fact that Quickstep take more of a ‘throw spaghetti at the wall’ approach, and some of the interest is in seeing which Quickstep rider will manage to get away for a chance at victory. Whereas Ineos have almost an entire team dedicated to domestique duties – there’s not even a tiniest of chances that Castroviejo slips away and takes an unexpected 2nd place (ala Asgreen in Flanders this year)…

I only said that Ineos (or Sky) have dominated the Tdf (my first paragraph).

I then pointed out: ‘Furthermore, we now hear that Ineos plan to do this for all grand tours, buying up yet more talented GT contenders.’

That doesn’t necessarily mean that Ineos will win this race.

This is not an issue that only affects this race, it affects grand tours going forward.

Sky/Ineos have had some obvious poor shows at the Giro but if the 2011 edition does get handed to Froome then they’ve won the Vuelta twice and have three podiums since 2010. That’s the same record as Movistar over that period. And while they’re not a one-day focused team they do still have a couple Monument wins and were getting top 10’s even in the 2010 season. I’m not particularly having a pop at you (so apologies if it reads that way) but I do think the degree to which they’re a TDF team can sometimes be overplayed.

It’s a noble proposal; but even if there was a Cap in force, who’s to say riders with GC ambition wouldn’t go to INEOS anyway?

Quick-Step don’t pay as much but classics stars head there if they have the ambition to win a classic and feel as though they could force their way into contention within a tightly-packed roster (and let’s face it, those two aspects often go hand-in-hand).

INEOS are dull, yes, but it’s clear they know what they’re doing when it comes to seriously targeting a Grand Tour – with the caveat that it’s only been with certain lead riders. They may have dominated Le Tour, but they’ve only won a single Giro and (for now, just about) Vuelta and the squads sent to those two tours have usually not been to quite the same standard or, at least, haven’t aided a winner.

Sky/Ineos have lost more Grand Tours than they’ve dominated. They certainly didn’t dominate Froome’s Giro win. And as dull as Le Tour has been in terms of eventual results, there’s more to Grand Tour racing (and bike racing in general) than the Tour.

I’m not a fan of the team by any stretch, by the way.

but even if there was a Cap in force, who’s to say riders with GC ambition wouldn’t go to INEOS anyway?

They may well do, but would the riders like Poels, Kwiatkowski, Moscan be there to work for them at a much lower wage? If Froome/Thomas/Bernal accounted for half the budget then smaller teams could offer Poels more money to be leader.

do we really think Poels is a potential leader? he strikes me as a classic ‘Porte’ ie a quality rider who is very happy in a secondary role with the pressure off… he has a 6th in the Vuelta and a 12th in the Tour and a bunch of stage wins but not much else to suggest he’d suddenly step up in a GT…

A team like dimension data would take Poels for a stage win and top ten I’m sure.

And its a crime we don’t get to see Kwiatkowski battling Sagan and Alaphilippe for stage wins in July.

In response to Graham’s post about Kwiatkowski battling Sagan and Alaphilippe in the Tour ( I couldn’t reply to that post).

I’d love to see Mathieu van der Poel in the Tour, either as a stage contender against the likes of Sagan and Alaphilippe or perhaps even as a GT contender in a few years from now. He is planning to lose quite a few kilo’s for the XCO Olympics in Tokio next year and will then be around the max weight (70 kilo or so) you need to be these days to compete for the podium.

I do agree with the INEOS analysis… but can’t help but feel it plays into the hands of some of the other riders too, a neutral may want a fully open race with a different dominant rider each day, based on recovery strategies and form.. but the route is quite balanced this year… without Froome or Dumoulin there will be less large gaps opened up by the Time Trials. Granted, G and Bernal should benefit from being part of INEOS, but recent TTT performances have put Jumbo-Visma, Michelton-Scott quite close. Yates or Bennett or Kruiswijk could therefore also benefit from a little advantage over say, Dan Martin who is likely to lose time with U.A.E.

While Thomas was incredible last year, there are doubts surrounding this year’s form. Similarly Bernal is inexperienced, he may get the order to ride for G and then he may need to really light it up in the Alps to secure victory (if it’s not guaranteed by then).

A rider like Nibali could benefit from the train. He won’t appreciate every day being long range attacks and do or die racing.. with the Giro in his legs.. but he may be looking at the lack of strong TT riders as a chance to mount a podium challenge again, utilizing his tactical nous and descending skills – the Galibier stage looks particularly tasty, for some who can get a small gap over the top.

Aside INEOS riders, there are 15-20 riders who on their day could out-climb the other.. i think that sets it up rather nicely. That number will be greatly reduced on Planche des Belles Filles – but time gaps should be more controlled.. that could lead to exciting racing right up to the final weekend, what would be a huge improvement on recent editions.

Some interesting ideas, as ever.

Not convinced that requiring teams to register in Switzerland would be sufficient to make a salary cap lawful (and it may not even be lawful itself – imagine arguing to a French court that a team could only compete in the TdF it it was registered outside France!) The teams would still have to follow the laws of the countries that they competed in, so the salary cap rules would have to comply with the legal requirements of all those places, most notably the EU.

There are many flaws (and the Swi idea was only a vague notion), but I’m sure it can be done.

Doesn’t rugby have some sort of cap? (And that’s in the EU – although that law might only apply to teams in the EU, I think.) And I seem to remember that football has or had various restrictions – not on money (obviously), but on transfer fees, number of players from certain countries, etc.

One thing I’ve learned from having a partner who is a lecturer in international law: laws can always be got around (although cycling may not be powerful enough to do that – it can’t be as easy as committing to an illegal war).

JE, all the examples of salary caps in sports that I can think of are in individual leagues in a single country eg English Rugby Union Premiership.

The English RU teams compete against their French counterparts who do not operate under a salary cap, and the Irish whose top players are centrally contracted to their Union.

So a variety of methods exist and not a ‘one size fits all’ model.

Cycling has teams scattered across the globe and riders living in different countries.

Inrng’s articles on Team Sky’s finances, for example, shows that their accounts do not even record the riders’ salaries.

This issue of the salary cap always seems to get raised come TdF time, and the rest of the season is fine?

Various Rugby Union leagues do have caps but they aren’t the same across the nations. In England there is a definite belief that several clubs regularly cheat the cap and this isn’t just whinging fan talk, although there is plenty of that too. Premiership Rugby reached ‘confidential agreements’ with a couple of clubs in 2015 (rumoured to be Sarries and Bath) and the former owner of Gloucester has claimed that other owners directly offered to show him the ropes on how to dodge the cap.

Another crucial factor in the rugby salary cap example is that it was something that the clubs affected agreed on and signed up to.

It was more of a negotiation rather than an imposition or penalty.

And introducing a salary cap in the WT would seem more like the latter at present.

Great summary as ever, much clearer and easier to digest that other websites.

Proofing duties – slight typo “Stage 14 – Saturday 21 July” should be “Stage 14 – Saturday 20 July”. Feel free to delete this comment once fixed!

And following established internet law I managed a typo in my comment while pointing out yours…

Great preview – looking at the route (for the first time… it’s been a busy year) it appears to have a very good mix of climbs… maybe one too many of the ‘short sharp’ on trend stages.

Plays very much into Ineos’ hands with the ITT and TTT, but with no froome/dumoulain and potential question marks over both Thomas (injury/form) and Bernal (too Green?) it means there are a lot of riders in the peleton who will surely never have a better chance on winning the big one.

Any idea how the bonus seconds will affect the racing. Is this to try and make the GC teams pull the break(s) back before the finishes, or reward the opportunist riders?

The idea seems to spice up some moments in a stage but the rewards are small, a sharp sprint here and you could lose double or more later on.

I still don’t really get the short mountain stages. If you want a seemingly impregnable Ineos leader to have a bad day and lose beaucoup time then surely a long mountain day makes this much more possible. That 110km Tourmalet stage will be the climbers equivalent of a bunch sprint.

The fashion for short stages is as nonsensical as most fashions: they’re not more interesting, a variety is more interesting. Three is at least one too many.

And the long stage – 18 (it’s not actually long, but it’s all relative: stage 15 is ‘medium length’ relative to the others; stage 12 is long, but not very challenging) – has a final climb that averages 5.1%; plus stage 20’s last climb is 5.5%. Hard to see how these will encourage individual attacks.

I know it’s not all about averages when it comes to climbing. A 5% climb can have some 10% sections, but if it does then it will also have much flatter bits where a strong team can pull back any individual attacker (not that there usually are many: as Wiggins said at the Giro, teams know that if they ride at a certain wattage – and they have the riders to consistently do this – an attack simply cannot escape: all the riders know this and we’ve all seen it).

Some of the best stages have been the short ones because riders can attack early on. But “can”, not will. Last year for example we saw the short stage in the Pyrenees without big attacks until the final climb but it was the longer stage that we saw the best racing. But in terms of Sky/Ineos, Froome cracked on the short stage.

Other than that Vuelta stage to Formigal where Sky got caught behind a split has there been another short stage that has shaped a Grand Tour (i.e not the final stage of Paris-Nice or the Dauphine) and led to significant time differences or a leader change?

Stage 19 of the 2011 Tour when Contador attacked early and the whole stage was total action on the way to Alpe d’Huez was only 109.5 km. That one is the obvious one that comes to mind.

Pre Sky dominance so doesn’t count….

The Agnello stage in 2016 was quite short, some 130 kms, but as I said elsewhere maybe it’s not a proper example, since the stage lasted anyay some four and half a hour. And in that same edition we had had a highly spectacular Dolomiti marathonian stage, 210 km long, over 6 hours, which was brutally exciting and great to watch. But the Andalo stage was great, too, and it lasted less than 3 hrs (not even a decent Sunday ride)…

The Stelvio 2014 stage was less than 140 kms (again, it lasted nearly 5 hours).

In 2015 we had a great stage to La Spezia, not exactly short (150 km) but less than 4 hrs of racing, then some great long stages later in the race.

On a short stage rider can attack “early on”?

But what really matters is that attacks come “far from the line”. And that’s not necessarily easier on a short stage, where all the gregari are still there and quite fresh, too. It’s way better to have a first part of the stage long and selective enough to lay out strategies, sending teammates on the front and/or wearing out rival teams, and *then* attacking *from far* in order to create more significative difference and long-lasting action. All the above requires a long-enough stage, even if it isn’t necessarily a marathon, let’s say some 170-180 kms (or some impressive mountains early on: in fact, riding time would be a more accurate reference than length, but the latter is more obvious).

However, that’s just theory: you’ve got a good deal of examples of great or boring stages in both the long and short stage categories. As in the “normal length” ones.

I’m not against short stages in general terms, they’re traditional, too, for those who like that aspect.

Yet, and I’m not referring to inrng, I believe we shouldn’t spread false – or directly silly – concepts about this sort of stages (“they produce more action”, “they’re more successful in audience terms”, “they allow people not to dope”…). Lots of what you read fostering short stages is plain nonsense and I’m starting to think it’s more about organisers wanting to go that way for different reasons (reduce road closure and TV recording, for example heli hours, costs, among others), then defending the abuse of this practice in course design with feeble marketing claims.

More than a couple of very short decisive stages in a GT will tilt the balance away from the sport’s core and ultimately reduce interest.

If what you say is true about organisers’ reasons to go for short mountain stages, I am happy with that, because I really enjoyed the ones I saw on TV. It would be win-win for me. Reduce interest? Maybe the interest of some 70’s-80’s cycling romanticizing dinosaurs I suspect some of you are, but not with me.

Some short mountain stages did not prove decisive for the GC, but they almost always provide action from the gun and there is TV broadcast to show it, because the entire stage is shown. There’s multiple narratives too, like the time cut suspense of sprinters or ill that get dropped right away. Or the GC riders that got out of bed a bit crooked and do not have a long stage to ‘ride into it’, having their teammates close gaps really early.

You can make stages longer, but I doubt it will make things harder. It’s more selective for GC riders to repeat doing threshold watts on longer climbs with little rest in between than having a lot of valley road soft pedaling at 100 watts one hard effort on a final climb.

I think that if you read thoroughly rather than roughly the text you’re answering to,especially the conclusive sentence, it would be of greater benefit both for yourself and for the conversation.

By the way, I could offer you an abundant list of short stages which didn’t provide at all relevant action from the gun, and not more than any normal stage, anyway (sometimes even less because the break isn’t allowed to form), but I’m short on time and I suspect it wouldn’t be especially useful.

JeroenK, a long stage with multiple climbs and only short valley sections provides a different test. It requires greater endurance, allows an increased possibility of long-range attacks and, generally speaking, provides a greater variety of tactical possibilities.

Like short stages, they’re often interesting – or, just like short stages, not.

I prefer balance and variety, with all aspects of a GC rider being tested.

Sure! Don’t get me wrong: I am all for more variety. I just don’t get the scepticism regarding short stages. I think we can agree that all stages that offer very little room for rest and team organisation are often interesting. Oh and please only include flat stages in area’s that are often very windy :-D.

I’ll say it again, because the most important idea is still overlooked: the crucial advantage of long stages (in distance or riding time) is that they are ridden at a slower speed. (As a general rule: the longer, the slower). When riders go slower, the importance of slipstreaming is diminished. The less advantageous drafting is, the less the attacking rider is penalised by riding in the wind. The increased speeds in contemporary times are a big problem: nowadays considerable pelotons draft themselves to the top of even the Tourmalet. Hence, very long stages, that can only be ridden at procession speed, will penalise defensive group tactics and be more rewarding for the individual attacker. It’s very important to find a way to reduce especially climbing speeds.

Ferdi, sorry, I call BS on that theory, because it’s much too simplistic. The benefit of drafting dependant on a lot more than distance. For instance, the gradient of the climbs in the stage and the amount of flat road. To that, average speed is often decided by the applied tactics, not on distance. Sometimes the first 2 hours of a loooong mountain stage are one big war to establish the final break, with very high speeds as a result. Also, in the top 10 GC riders, sometimes even in the top 20, teams will start to protect the position of their riders by chasing early and keeping the break on a short leash. This is also quite detrimental on attackers, regardless of how long the stage is.

All those factors apply, which doesn’t change the fact that arriving at Luz-St.

Sauveur after 350kms through 7 HC climbs will, caeteris paribus (all other factors being the same), will generally cause the bunch to climb the Tourmalet more slowly, and will generally cause attacks from the bottom of the climb to be more successful, than if it is climbed after only 100kms through just one col.

I find it a little tiring that when discussing cycling, and analysing the influence of one single factor, people fail to consider it caeteris paribus, and evade the factor by drowning it in a «multifactorial complexity» that makes understanding each factor in its own right quite impossible. It’s the same when I defend banning cyclo-computers in TTs and somebody answers that the problem is TTs are poorly televised, failing to consider the initial point.

You go tell a sports director to only focus on one factor.

It’s not about focussing on one factor. It’s a about considering each factor «all other factors being equal», so we can see the effect, positive or negative, of each one of them. Not so hard to understand.

I like how you posted a picture of Froome on the podium above–probably as a tribute to him and reminder to wish him well in his speedy and full recovery. Chapeau!

Hope he’s on the mend but I wanted the photo of the podium and the Coupe Omnisports porcelain trophy. Years ago someone one came up for sale in an auction house, still kicking myself for not getting the ultimate fruit bowl.

Interesting how stages 1 and 2 start in Bruxelles and finish in Brussel on the profiles. Is that meaningful from a language or cultural perspective?

Both, the country has two languages (they speak German too in a small corner) so this covers both the Flemish and French speaking parts. It’s too strong to say the country is “split” but each part is relatively autonomous from the other with devolved politics, separate TV channels, newspapers etc and the extent of this separation is itself a political question with separatists in Flanders.

I read somewhere that the letter ‘x’ is barely used in the Dutch language (0.04% occurrence) and apparently the Italians do not use it at all.

Xilofono

(and a decent deal of others)

That’s really an Italian mimicry word though isn’t it?

However I shan’t argue as I don’t speak either Dutch or Italian.

Rather than a mimicry word, it’s a composite word from the Ancient Greek roots, from which most of the Italian words with “x” (not just starting with “x”) come. You’ve also got quite common words – especially nowadays – like “xenofobia” (same pattern). Note that although the root is Ancient Greek it’s not an ancient word!

Curiously the jota of jérez (the wine which gave “sherry” in English) also became an “x”: xeres. Though, curiously enough, in Italy we’d rather call it… sherry!… instead of using the proper Italian word (and generally avoid drinking it 🙂 ).

They don’t have ‘x’ in welsh either

If you get 8 seconds for being first over a bonus summit and then finish in 2nd place at the line for another 6 seconds that’s a total of 14 seconds. The winner for the day only gets 10. This seems unusual to me.

Not to the riders who are going for polka dots.

Thank you Inrng for the uncounted hours of under (un-?) compensated work that makes the TDF exponentially more enjoyable year after year.

I think these bonuses should help who, as the saying goes “packs a good sprint”. Valverde could go for the polka-dot, and look at the GC from that angle. But those seconds are meant for Alaphilippe, obviously.

Hi – just want to say a HUGE THANK YOU for the previews and write ups you. It adds so much to I think so many people’s enjoyment of the sport. Happy to be punting about in INRNG jersey and cap to spread the word!

I really want to support the site through the kit as well. I have one of the original caps but have been looking to buy a jersey. It has been unavailable for a while but Prendas says new kit coming in 2019. Looking forward to it and thank you for my favourite cycling website – both the posts and the comments.

I think the Polka Dot Jersey is sponsored by Carrefour and not Leclerc, judging by the picture – they won’t be so happy that you advertise their rivals, hope you don’t get sued !

Old Picture 🙂

https://www.letour.fr/en/news/2018/e-leclerc-to-take-polka-dot-jersey-to-new-heights/1275980

My bad.

Ah don’t worry, I’d missed the news too. It was this article and a subsequent google that alerted me to it!

I was unaware of this too ( even though I have loyalty cards for both supermarkets). I had noticed that Carrefour virtually ignored the TDF last year, no instore promotions or publicity. Lucky that LeClerc has the same colours in its logo, I don’t suppose most people will notice the difference.

I used to like it when Banette sponsored , the local branch bakery had a bike draped in yellow mounted above the door for the duration….

It is often suggested that INEOS, with thier budget, dominate GTs by relentless pacemaking in the mountains and on the flat. Could thier strategy also assist other teams with one decent GC candidate (Trek-Segafredo with Porte, Bahrein Merida with Nibali, Mitchelton with Yates, AG2R with Bardet…) but without the same support to manage gaps on flat stages and close gaps to GC rivals in the mountains. In effect INEOS manage gaps both for themselves and for the weaker teams.

This is true in that instance.

But INEOS put time in to them in the TTT and TT, so then they need to attack in the mountains. INEOS domestiques bring them back, they are in the red, they get dropped in the final couple of KMs.

It can assist to an extent, in as much as it largely ensures a steady pace, and discourages attacks that otherwise may need to be followed…

But there are two large benefits to the Ineos leader whose domestiques are doing the pace setting, which aren’t available to other riders:

1) The Ineos leader can tell the domestiques exactly what pace to ride at – slow it down a little if they’re suffering, or speed it up if they’re feeling good and think they can drop some rivals. A rival team leader obviously doesn’t get that benefit – he has to ride at the pace of the domestiques whether it’s too slow, too fast or just right.

2) The other obvious benefit is simply having some friends with you in case of emergency (puncture, mechanical, crash) and simply for a bit of a morale boost.

The Ineos train may help some contenders achieve a higher finishing position than they would do otherwise, but it’s still a very hard machine to defeat.

INEOS is a hard machine to defeat in le Tour but so is Mercedes in F1, so are the New England Patriots, so are the Golden State Warriors, so a Juventus and Barca.

Is it not up to other teams to come up with strategies to defeat INEOS? To me it feels that most teams are content to settle for top 5 on GC rather than risk a worse outcome in order to win.

There isn’t really much to compare those to “Have the money to have the best domestiques in the peloton”. It’s not exactly some kind of mystery strategy, and unlike top football clubs, it’s generally boring to watch. Some domination can be good to watch just for the amount of talent on display (I think people will remember the Warriors for decades), and some is just boring, like the rugby team that wins by brute force instead of creativity. I don’t like Manchester City but they’re at least good to watch, but there’s nothing good about watching a Grand Tour be strangled by brute force.

I suppose the blessing is that they only care about the TdF, which has never been my favorite race. I respect the race a lot, but it’s a bit like Wimbledon, or the Masters in Augusta- sometimes too consumed with it’s own importance in history.

Also the way to beat them is to “get more money into the sport” which sounds well and good but risks turning cycling into even more of a club football situation where either you have a rich sugar daddy e.g. Murdoch/Ratcliffe/Some sovereign wealth fund by a country with a non-existent human rights record, or you don’t. I don’t like that in football and I don’t want that in cycling.

Who are the Warriors?!

How quickly we forget.

(I’m guessing Rugby, Richard – it sounds Rugby-ish. Then again, it sounds ice hockey-ish too. I think SYH is spot on, though.)

I’m guessing that’s Golden State Warriors, the pre-eminent NBA team for the past few years.

if we assume it’s the Wigan Warriors… pedants corner here, as most of their glory days (Hanley, Gregory, Edwards etc) pre-dated when they added the Warriors moniker in 1997

Aye rugby league another sport diminished by the murdoch millions.

Happy days at Central Park when you could watch the best team in the world for six quid and have a pint in the Griffin

Thanks for a fab summary!

Hoping to be there for the Nimes and Pont-du-gard stage work-be-willing.

Served with a reduction ….. just sublime as usual – Thanks INRNG

Really enjoyed that line too, along with of course the whole post. Thanks very much, inrng, I feel knowledgeable about this year’s TdF now 🙂

That stage on Saturday the 8th (Macon to St Etienne) looks a monster. It’ll be one for the break you’d think, but it’ll be all about the right consistency of break. No GC threats, otherwise you can see it being a tough one for stragglers if they’re racing.

Given that the Sunday appears to be better for a GC battle it might end up being detante leadig up to it.

Otherwise a Battle Royale awaits on the Tourmalet. I’m sure there will be plenty of twists and turns before and after, but that is probably the first one where the gloves are off. The Planche de Belle Filles comes to early for it to have too much meaning in the grand scheme of the GC unless you have a Skytrain.

I was thinking that Sunday (stage 9) looks more like a Bastille celebration of French pride courtesy of J.Alaphilippe

Thanks for the summary!

Any merch in stock to say thank you in advance for the coverage?

Use the contact button at Prendas and I imagine those splendid chaps will be happy to let you know when stocks become available 😀

Thank you INRNG!

exceptional work . thank you.

So do the short and hard stages play into strong team’s hands, or play against them? I’m curious what you all think.

I can see both sides have potential: on one hand, it does not allow a team enough time to set a high pace to burn off teams like they would on a ‘set piece’ long stage with a large final climb, and on the other hand, if the team has major depth, they can really dominate potentially.

Note: this is not specific to Ineos, Astana & Movistar would also be considered strong teams (and maybe Jumbo and Michelin).

When short stages were a novelty they caught out the big teams a couple of times and it was super exciting, so organisers thought we should have more of them. But I think the big teams have adapted now and know how to control them.

Like in F1 there was that amazing Canada GP where all the tyres fell apart, so organisers decided fall apart tyres for every race was great idea. Teams adapted and the drivers adapted and made it boring again by, as Hamilton put it “Driving like a granny”.

If something is exciting by being a surprise its hard to repeat.

somehow I had completely missed that there were two shorts stages at the end!

that’s great… I’m am always positive and no TDF has been better poised in the last 7years than this one… very hyped….

but admittedly it could all be sewn up by final few stages… Bernal could destroy the field.

” …the best sprinters finally reunited in one race…”.

Kristoff and Groenewegen are in, indeed – Sagan isn’t quite much a sprinter, although he can sprint, of course.

Matthews and Degenkolb, assuming they’re riding, aren’t among the top sprinters anymore – if they ever were: they tended to be something different, and better.

Kittel and Cavendish who surely were, haven’t been riders from some time now, albeit Cav might be quick to come back and make a Petacchi taking advantage of a middle-level field.

This season Greipel’s been brilliant only at La Tropicale Amissa Bongo, and at 36 he might well be excused.

OTOH, having a look at the sprint stage winners in recent GTs, Gaviria is out, Ackermann should be there… in 2020, Démare shouldn’t be in, either (but the articles on the subject are from some time ago and maybe his recent good form might change things?). No Sam Bennett, either, FWIW.

I wouldn’t say it’s an exceptional sprinters field. Rather good, no doubt, but pretty similar to any recent Giro. I hope this might allow some new talent to emerge, the rest of them is essentially known value, that is, very good athletes but none giving an impression of pure speed primacy.

Degenkolb isnt riding

The Tour has sent mixed messages to sprinters in recent times. The issue has always been about them making it through the mountains, but there has to be something for them to put themselves through the mill to get to Paris. In the last few iterations of the Tour it has felt as if the support for sprint finishes has dwindled, and with it the number of teams dedicating themselves to this pursuit. I have no data for this, but teams set up as sprint trains have not been abundance that is for sure. Maybe, also, it is that there is not the same sprint talent. I’m sure some fine analysis by Mr Inrng would show if this ‘feeling’ is true or not.

Agreed with you that there seem to be fewer trains about, but I wonder if this is a result tactics evolved in response to the sprint train? I also have no data, but it seems that instead of coming off the wheel of a lead out man/men to take the win, sprinters maybe now seem at least as likely to follow a rival’s wheel before a final kick? As one example, perhaps in response to the dominance of QS era Kittel, Cavendish didn’t rely on his own DD train (I don’t think) but became a surf the wheels sort of finisher, more like the often lead-out-less Sagan?

p.s. Huge thanks to our Host for this preview and the rest of the coverage throughout the year, the evident hours and hours put in are very much appreciated.

You didn’t mention Ewan and Viviani, both of whom have had mixed 2019 early seasons, but both of whom need to be mentioned among the top sprinters in the peloton.

I didn’t, obviously, because they were at the Giro, that is, it didn’t make much sense to highlight their presence here… too. The stress was on the guys who will do the Tour (or I thought so) while not being at the Giro, and those who were at the Giro but won’t be there for the Tour. My point is that the two fields are comparable and neither is especially notable in terms of concentration of top sprinters, hence my lack of agreement with inrng’s sentence I quoted above.

Ewan and Viviani are either among “the best sprinters” or they’re not. I took Inring’s statement to mean the best sprinters currently riding are gathered for the TdF. Viviani’s form in the Giro was lacking, but he seems strong and confident now. Ewan also appears to be in pretty good form. Gaviria, OTOH, has had a spotty year, doing well in early, lesser races, and looking not-so-great at the Giro.

And I don’t know why you mentioned Kittel, who hasn’t had results, and isn’t going to be at the TdF in any event. Cavendish is also irrelevant, though I don’t think if it’s been announced if he’ll be at the Tour or not.

Uhmm… not that hard to understand I thought, but apparently it was.

Gaviria, and Démare are surely among current top sprinters (winning several stages at the Giro and the TdF in the last couple of editions) and *won’t* be at the Tour – they were at the Giro. You may add Ackermann, because of his more recent results.

At the TdF, you’ll essentially get Groenewegen. And let’s count Kristoff, too, albeit he’s not as shiny as before.

The rest being more or less equal. In short, the field of top sprinters is as *reunited* as at the Giro, that is, poorly so.

The general lack of racing for Sam Bennett (due to well-known reasons), Matthews’ concerns about his prep, Degenkolb’s complicated career, Kittel’s woes, and old age being harder and harder on Cav or Greipel all add up to a lacklustre situation when sprinting is concerned.

Uhmm, your sarcasm and condescension are unnecessary. No one who has watched the races this year would say that the Gaviria of 2019 is remotely close to the Gaviria of 2018. His start to the year was less impressive than expected, and the last couple of months have been strikingly weak. He won a stage in the Giro only due to a DQ, and aside from that he’s barely made a noise unless you go back to the UAE tour in Feb. I think his team did him a favor by not sending him, and in any event Kristoff has had the stronger year.

I share the opinion of many commentators when it comes to Demare – he seems to have all the potential in the world, but it’s usually a surprise when he wins a top race against top competition. I’d go so far as to say that Bora has three sprinters who are better. And speaking of BH, it’s no surprise they’re only sending one of those three. Yes, Bennett and Ackermann are among the top sprinters, but who on the Bora team is the most likely to win multiple stages in the TdF? Of course it’s Sagan, the most exciting rider in the peloton. It’s hard to call any race he’s contending for lackluster.

I agree that overall the sprinting field is somewhat lackluster right now. This was certainly the case at the Giro, where a young and still largely unproven Ackermann unexpectedly dominated. It remains to be seen how lackluster the Tour sprints will be. I’m personally looking forward to finding out.

As always, thank you for this and all your race previews. Excellent work.

A minor comment on timing: During the Giro your posts went live at around 10 or 11pm for those of us in California. So I (and most in the Americas) didn’t see them until the morning of the stage. Of course when I get up in the morning the stage usually has only 1-2 hours remaining, so at that point a preview is largely moot. I assume you were publishing in the early morning, European time. If it is possible to move the timing up to push these out late the night before, that would be nice.

Of course our author can correct me, but I believe in the past they have said posts are written in the morning over an early breakfast (though, not necessarily applying to the GT preview posts).

Even when the stage is half done, I have found the previews helpful to give a deep dive into the parcours and how the finish might shape up, if its not a day for the breakaway.

We’ll see with the timing, it’s always going to be hard to suit each timezone. They tend to get finished the evening before but timing varies and cueing them up to go online in the morning of the stage on Euro time means there’s enough time to make a midnight or breakfast edit if needed etc

The mountain jersey is sponsored by Carrefour, not Leclerc.

No longer: see BenW’s post above.

Wondering why the first rest day is on a Tuesday. I only recall the rest days moving off a Monday when there is a foreign start. That doesn’t apply here as the race rides from Belgium into France. Any reason for the Tuesday rest day in 2019? Perhaps a long transfer?

Since bastille day falls on a Sunday, the French will have Monday off of work.

Correct for Bastille Day on the Sunday but there’s no holiday on the Monday. I think it’s just down to having the rest day in Albi rather than Saint Flour.

In France national holidays falling on a weekend do not transfer to a weekday. If the holiday occurs on a Saturday or Sunday it is effectively lost – at least for those working Monday – Friday.

Funny how the two race days start in Bruxelles and end in Brussel. Got to love Belgium…

I like it that all the HC climbs have double points for the polka dots – as it’s a King of the ‘Mountains’ jersey rather than King of the Hills. I think Alaphilippe will struggle to keep it off Landa’s back this time around.

Julian Alaphilipe, winner of KOM, rode into the history books as he became the first rider to win four HC climbs in one edition of the TdF since the inception of this category in 1979. The 26 year-old Frenchman was the first on top of Glieres (stage 10), the Bisanne (stage 11), the Madeleine (stage 12) and the Tourmalet (stage 19)

I see the ‘Sky/Ineos have killed the TdF’ comments are back in full seasonal bloom. But it’s confusing because Brailsford I think implied that he was spoilt for choice with possible sponsors… if true, cycling must be quite healthy? After so many years of this discussion going nowhere, perhaps it’s time to instead ask hard questions about what are the rest doing wrong?

As for the ‘buying the best riders’, I’m always impressed by how Sky/Ineos keep the team unified when so much talent and so many egos are on one bus… is it really just the high wages? I’m not convinced that money can buy obedience like that.

Anyway, Ineos critics needn’t worry: all empires crumble eventually, irrespective of wealth.

You know it’s always possible that Brailsford wasn’t telling the truth. He could be talking up his own business, which would be a very normal thing to do. The discussion is going nowhere because nothing is being done about it. That doesn’t make a discussion not worth having. You’re not convinced money can buy obedience? Really? You can’t think of many, many instances where money does buy loyalty? You haven’t offered any arguments against anything that anyone has said above.

I think part of it is high salary and immense team infrastructure (rider support), then part of it is good selection by management — identifying riders who fit the mold and are happy in the role, and lastly, they reward teamwork by giving these other riders who might have winning ambitions opportunities for 1 week, 1 day or stage glory, since their main riders tend to solely focus on the GTs that leaves a lot of other races and stages to scoop up.

On paper this looks to be a very exciting route. The only thing I don’t like, and I mentioned this before during one of the Dauphine previews, are the short mountain stages. One would have been ok, but three is definitely too much. They could have left the penultimate stage as it is, but I don’t like the Tourmalet and Iseran stages at all. I can’t see much happen there with such a short run in to the final climbs. These stages needed at least one more climb and more kilometres to tire the legs.

I always wonder about criticism like this; is there a calculation of fatigue that can be applied to route choice?

And what of external factors like the weather, how much more fatigue can wind, rain, heat etc add to riders’ workloads?

I sort of have a feeling that Ineos can make a go at estimating wattage / energy use for an individual stage and perhaps this is part of the reason that they ride at the front much of the time – it allows for control of their estimates?

I might be talking absolute bumph of course but I think that time of such in-depth calculations is not far off, if it hasn’t already arrived.

Lots of teams measure the effort like this, you can measure the watts and calories and the work done for the day. Sunweb I think have a special software package for this which allows them to put in a route and then get data based on the vertical gain etc about the likely effort, others use things like Training Peaks to review etc.

Is there going to be an ics file for seeing the 2019 tour in calendar apps?

http://inrng.com/2018/06/tour-de-france-2018-ical/

One thing I’m thinking is the difference between this Tour and the Tour where Wiggins won when Froom held back to support Froom… -remember that?

This Tour I don’t see Bernal holding back to support Thomas. Between Bernal’s rising form and Thomas’ lesser form, this is a different situation.

& the way things have been going, one of them may crash in an event leading up to the Big Top.

We gotta just be patient and wait another week to continue speculating for 3 more weeks so We can look back and ponder what We witnessed.

“where Wiggins won when Froom held back to support Froom… -remember that?”

You know I meant when Froom supported Wiggins when Froom seemed stronger…

-Oh the red Burgundy.

Not one stage in the west or northwest of France, unless you count the Pyrenees. Tour of East France?

Are the lesser sums for various prizes on each stage also shared amongst the team? I could see being a low-paid rider sprinting to come in 10th to be able to buy his kid a new bike…

Thanks for the entertaining and useful guide.

The east of France has more exciting geography for the Tour de France, the more the race ventures west the more it’ll have repeat bunch sprints and the race wants to avoid that.

As for the prizes, yes all are put into a collective pot and shared. The same for fines which tend to be netted off as well against prize money. 50 years ago these prizes were a big deal for riders but today they’re not. The race publishes the prize money totals for each team every week and they’re a good proxy for how active and visible a team has been, eg stage wins and yellow jerseys and they score big, get in a some breakaways to take intermediate sprints and small KoMs and this adds up, do nothing and a team’s prize pot is small.