Roger Walkowiak has died aged 89. “Winning à la Walkowiak” is a term used today for an easy win or an unexpected triumph. It’s used in cycling and beyond, a French politician can get elected à la Walko too. Walkowiak felt wronged by this label, his triumph in the 1956 Tour de France was mocked and this turned into a sadness that weighed on him for years.

Get a map of France, put your finger in the middle and you find the city of Montluçon where Roger Walkowiak was born in 1927. The son of a Polish factory worker and a French mother, Roger grew up in Montluçon when it was a busy industrial city.

He joined the Dunlop factory cycling club, the rubber company has long been the town’s biggest employer and today its factory is still working, albeit amid crumbling buildings that signal better days. After completing his military service Walkowiak found work in a local bike shop and resumed racing, getting enough results to turn pro for the local Riva Sport-Dunlop team.

Walkowiak’s first year as a pro in 1950 was not an auspicious start, he caught a cold six times in five months. Things improved in 1951 and in a stage of the Circuit des Six Provinces – an event later merged into the Critérium du Dauphiné – he crossed over the Col de l’Epine first only to get beaten for the stage win in Aix-les-Bains by Gilbert Bauvin, a name who’d become a thorn in his side later. This and more was enough to get him a start in that year’s Tour de France. While the sport had its nascent trade teams, the Tour invited national teams, and regional teams from France. It sounds parochial today but reflected the vast supply of riders as almost the entire the peloton came from France and countries along its border; plus the Netherlands and minus Germany. The British were seen as exotic and enjoyed the media coverage we see applied to Chinese or Japanese pros today; in 1956 the sole British starter Brian Robinson, invited by a French regional team, was labelled “Phileas Fogg” by the media as if to imply he’d travelled from afar.

Walkowiak’s career progressed with a win here or there and some solid places like second in Paris-Nice – then labelled Paris-Côte d’Azur – and a top-10 in Milan-Sanremo. His ride in the 1955 Dauphiné impressed many, he was almost the equal of France’s best rider Louison Bobet on all the main climbs including Mont Ventoux and finished second overall. But he never made the French national team for the Tour de France that year. Bobet himself said Walkowiak deserved a place in the national team. Yet he wasn’t picked for the French team and rode for regional Nord-Est-Centre team run by Sauveur Ducazeaux and abandoned on Stage 11 with a saddle sore.

1956, the big year that nearly wasn’t

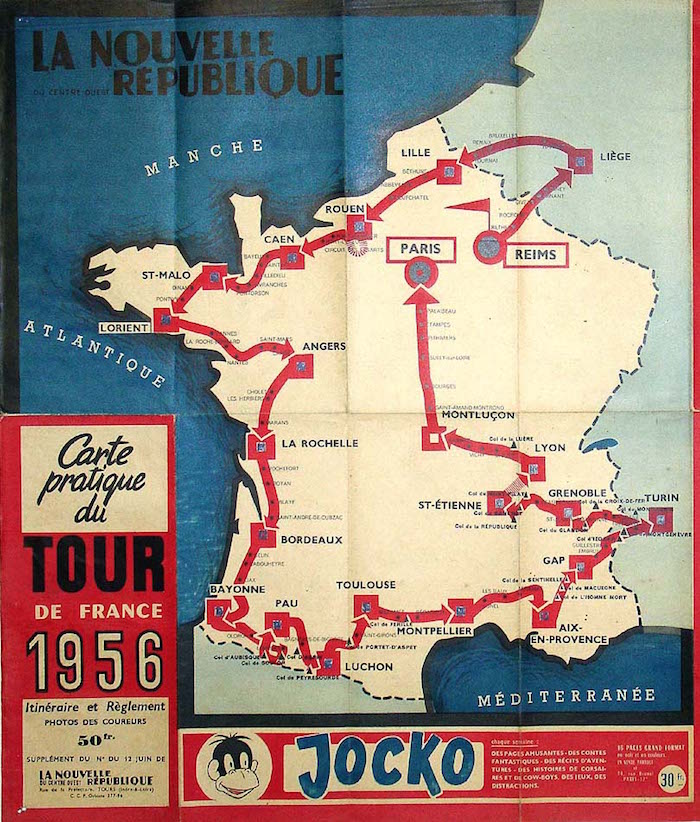

Walkowiak may have won the 1956 Tour de France but starting the race wasn’t a given. Earlier that year Sauveur Ducazeaux was managing the French team in the Vuelta a España, then run in late April, and he picked Walkowiak. Things started well with a team time trial win and then a stage win for “Walko”. But team leader Bobet wasn’t having a good Vuelta and pulled out, other French riders followed and Walkowiak joined the exodus, taking the train home one morning instead of starting the stage. Ducazeaux blew his top and swore he’d never select him again. Come July and Walkowiak again missed out on the French national team and qualified for the the regional Nord-Est-Centre team… managed by Ducazeaux. It took the intervention of Raphaël Géminiani and a handwritten apology by Walkowiak to start the race. He raced but others did not, with Gino Bartali, Fausto Coppi, Ferdi Kubler, Louison Bobet, Hugo Koblet and Jean Robic all absent for varying reasons. Federico Bahamontes and Charly Gaul were tipped to win but the two star climbers had a route ahead of them with few mountains.

The race began as predicted with André Darrigade of the French national team winning the opening stage in Liège and wearing yellow. Bahamontes, the Eagle of Toledo, got plucked alive during the opening days and lost 30 minutes on one flat stage; Gaul surrendered 10 minutes on another flat day. Walko meanwhile was regularly at the front of affairs and Stage 5 placed was part of a group of 20 riders who put ten minutes into Bahamontes and 15 minutes into the field. The next day Walko made another breakaway that put over five minutes into the next group and 11 minutes on the bunch.

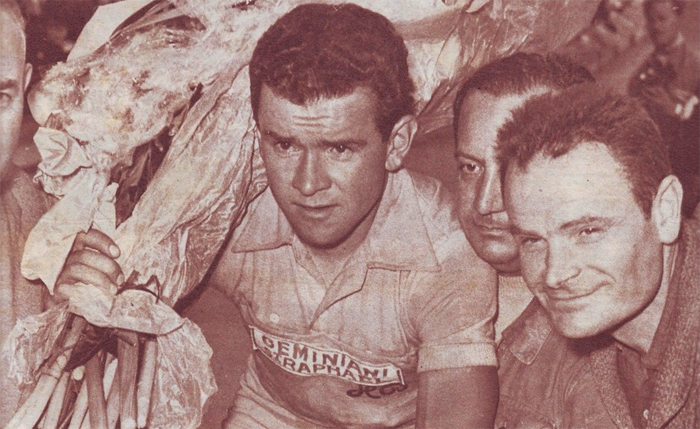

Stage 7 was the decisive day. On the roads from Lorient to Angers Walkowiak infiltrated a breakaway of 35 riders that finished 18 minutes ahead of the bunch led home by a dejected Darrigade. While Italy’s Alessandro Fantini won the stage, Walko took yellow thanks to time gained from the other successful breakaways in prior stages. Walko was the new race leader but the story was the “Waterloo” of the French team, their crushing loss rather than the regional rider’s gain. L’Equipe’s Antoine Blondin, the playwright who chronicled big sports events for them, labels Walkowiak a “poujadiste égaré dans le Bottin mondain” which almost impossible to translate but think of a “petit-bourgeois lost among aristocrats” and either way Blondin mocks this modest rider leading the great race.

Walkowiak was part of this maxi-breakaway and so were Belgian Jan Adriaensens and Dutchman Wout Wagtmans and each would earn a brief spell in yellow as Walkowiak lost time in the Pyrenees. He got his climbing legs in the Alps and, over the Izoard, matched the best that Bahamontes and world champion Stan Ockers could throw at him. He took back the yellow jersey but Gilbert Bauvin was closing in, especially when Walkowiak crashed on the stage to Lyon and had to chase. Still Walkowiak rode into his home city of Montluçon in yellow with one stage to go. These days the final stage is a victory parade with a criterium at the end but in 1956 they rode from Montluçon to Paris, today a four hour car journey and a nine hour stage in 1956. “Bauvin and Adriaenssens attacked me 20 times” said Walkowiak. Whether the count is exact we don’t know but it shows the fight went to the end.

Walkowiak won his Tour and if the win was unexpected, the result was beyond dispute. L’Equipe praised a powerful Walkowiak who rode better than everyone else in a lively race. Here’s Blondin again in his final column:

“The most athletic Tour de France we’ve ever known… …A moral ending fit to give satisfaction to every reasonable person… His win confirms a fact. Walko was the bravest, the most constant, the most healthy.”

Quite the volte face? L’Equipe and the Tour came around to Walkowiak but was this an appreciation of his ride or a commercial need to promote the winner in order not to devalue the race itself? Blondin, no stranger to a bottle or three of wine, was probably the last person to take the corporate line, in fact his piece praising Walkowiak criticised other aspects of the race. Later on the Tour organiser Jacques Goddet even dedicated his memoirs L’Equipée Belle to Roger Walkowiak to show appreciation for this edition of the race and its winners. Other newspapers, newsreels, radio and television were less generous and Walkowiak began to lament his win, “I felt as if public opinion thought the Tour was too important for a rider like me“.

From Tour champion to tourneur

Walkowiak’s career continued as it had been before: without further crowning success. He returned to the Tour de France in 1957 as part of the Peugeot team only to see Jacques Anquetil emerge as a star, the darling of the public. In a race with a high attrition rate that year he abandoned on Stage 18 becoming one of only six “defending” champions (Froome 2014, Hinault 1980, Thévenet 1978, 1976, Bahamontes 1960, Anquetil 1958). Walko would soon quit cycling too, his career harmed by a parasitic infection following the Tour of Morocco. Out of work he returned to factory where he was once an apprentice and resumed his career at the lathe as a tourneur. He ran a service station and tried his hand at farming too. He avoided the media for decades until an interview with L’Equipe in 1985. “They stole my Tour, they’re bastards” he said about the Parisian media who he accused of underestimating his win and the effort involved.

More recently in an interview with French TV he broke down in tears when asked about his Tour de France win, still hurting at the accusations that he won the Tour de France thanks to a fluke breakaway on a flat stage. He said he never talks about the win with his wife either, the subject was too hard to broach. A more recent interview by Bicycling’s James Startt saw Walkowiak telling the story from his side.

What if Walko had lost?

Historians and sports fans share the love of the counterfactual, the “what if?” scenarios if something had turned out different. What if Gilbert Bauvin had won? He was the leader of the French national team but hardly a great champion either. Maybe the Tour would have made him into something bigger but his palmarès prior to the Tour was only marginally superior to Walko’s thanks to a few wins and two spells in the maillot jaune. He too made the maxi breakaway that gained 31 minutes. So maybe we would have a win “Bauvin style”? That said he was still more of a media darling than the modest Walkowiak.

Conclusion

Did Walkowiak get lucky? Yes because for various reasons several star riders did not start the 1956 Tour de France. Yes because he joined a breakaway that to took 18 minutes on Stage 7. But you make your own luck. He was in the successful breakaway for two straight days before the 18 minute move which meant he’d already gained time on rivals including those that made the maxi-break while the pre-race favourites were floundering in the cross-winds.

When the Tour went into the Alps he climbed back into the yellow jersey and was matching the best on the big climbs. His lack of style and his self-effacing modesty didn’t endear him to the media but he won a race with a record average speed.

The race had big breakaways staying away. The yellow jersey changed shoulders eight times with Walkowiak losing the lead only to win back the yellow jersey thanks to some valiant riding. If only every Tour could be as exciting.

- This piece is a reprise of a post done to coincide with last year’s Paris-Nice’s visit to Montluçon last year but hopefully worth revising and reviewing again in memory of Roger Walkowiak.

Great article! Missed it last year…thanks for re-posting.

I missed it as well first time round but a really interesting read, thanks. It’s a real shame that he could never appreciate such a monumental achievement.

Walkowiak, despite the derision, is one of the most well known legends of the sport. Everything i’ve read about him has always spoken of him as a good person who should have been treated better. The whole ’56 Tour was an outlier from the usual, and as such will always hold a divided place. But any rider who wins a Grand Tour absolutely deserves it.

It was only a short tenure as “oldest living Tour winner”, now passed onto Federico Bahamontes. Roger was a good cyclist, and a good winner. Will be missed as these legends are becoming few and far between.

Don’t worry! As time continues there will always be the new “oldest” TdF winner and as we age, the current and recent past winners will become the new “oldest” TdF winners!

But somehow i don’t see Oscar Peireo going down in history as a legendary winner, or Jan Ullrich. There are Tour winners who will become the “oldest” but when they do there won’t be real fanfare in comparision to people like Walkowiak or Kubler.

In the ever profesionalizing world, legends are harder to make and riders become more cookie-cutter and less interesting characters.

Ullrich quite probably will, besides being for sure a legendary runner-up and a legendary overfeeder (but probably he was forgetting the cortisone diet part).

One of the most naturally gifted cyclists in decades (he was receiving less natural gifts, too, but that doesn’t change the substance – a prototype for the concept “a clean cycling world would have benefited him, actually”).

Ulrich definitely will, but absolutely Pereiro won’t

Very enjoyable read, and in 1956 Le Tour truly was a tour around France.

A pity that he could never overcome his feelings about the what the media said – they never were any more than tomorrow’s chip wrappers.

There will always be those whose TdF victories are seen as lesser in quality because of a supposed paucity of decent opposition – Nibali being the most recent winner who has this thrown at him (which seems harsh considering how brilliant he was in the wet cobbled stage).

Particularly when you look at how many have won using nefarious means, Walkowiak should have considered himself a true winner.

Exactly – it’s total BS to downplay these supposed “easy” TdF wins.

– 2014 Nibble’s win – he rode like a champ in the P-R type stages. That was brilliant and obviously Froome/Contador fell out of the race, but that was because Nibbles’ directly forced them to ride way beyond their comfort level. Absolutely, Nibbles was not gifted that race at all.

– How can you “easily” win a TdF? The winner, even in a year without the top GC rider, still has to beat 200 of the world’s best over 3-weeks, hundreds of climbing kilometres, dangerous descents, sprint stages, etc.

Which is another example of people’s opinions differing from reality – Nibali’s ride on wet cobbles in 2014 didn’t put Froome under pressure, because he never got to the cobbles – he’d already crashed out of the race on the very wet roads.

And the damage had really been done to Froome in his crash at the beginning of the stage the day before, when he, Mollema, and Ion Izagirre went down.

Mike – I think you should remember that Froome was out of place from the start and was caught off guard by the pace set by Astana and other teams who took the cobbles seriously.

Obviously opinions differ, and you believe Froome lost that race, but I believe otherwise that Nibali was on point that entire TdF. That TdF started way before the mountains and Nibali recognised that.

If Nibali hadn’t set such a blistering pace and he, himself played it safe and sat back with the other GC guys, Froome wouldn’t have been forced to chase at such a desperate pace, which inevitably forced him to crash again and abandon. Nibali’s pace also forced Contador to lose time, which forced him to take too many risks in subsequent stages before he too crashed out.

The media and his status mattered though, he should have made fortune on the criterium circuit but seeing him give up he sport so soon and return to the factory, the factory floor even suggests he never had the chance.

Good point – it probably mattered a lot more back then.

Froome seems to be the only Tour winner these days who does crits (even though he can’t need the money). I often wonder if he might have won the Vuelta by now had he trained for it optimally. Maybe this year he’ll decide that winning a different grand tour is more important than extra cash.

That you don’t have to stick to a ridiculously rigorous diet to do crits may also be a factor. Froome has been visibly heavier for the Vuelta than he is at the Tour, and while his Vuelta weight is a bit slower, it’s almost certainly healthier.

RIP Walko. Winning LeTour one time, no matter how you do it, doesn’t make you a great champion. I think Roger expected otherwise, but when you don’t win much else, you don’t get a lot of respect even as a winner of Le Grand Boucle. The modern Walko might be Carlos Sastre?

Oscar Pereiro’s the modern Walko – Sastre was at least a really solid GC rider at his peak and he didn’t benefit from a lucky breakaway.

CA – Agreed. Pereiro certainly fits the mold…so much that I didn’t even think about him 🙂

Well, Pereiro didn’t “win” the race so to speak. Landis “won” the race as he completed the course in the fastest time. At least Walkowiak won his Tour. But i’m aware this won’t be a popular opinion :p

I’d forgotten about that too. Thanks for the reminder. On the Landis subject the “interview” with Floyd in the current ROULEUR is hilarious. Stuff like this is why it’s the only magazine I pay good money for!

Don’t really understand that. Landis wasn’t restrospectively found to have cheated, but caught at the time. Perreiro was the fastest finisher among those who weren’t caught breaking the rules.

Nick – Landis had the podium ceremony and procession on the Champs Elysees, so in many minds he won.

I don’t understand why a doping control sample can’t be tested overnight and the results published the next day. For example, Floyd’s sample was collected one afternoon, then 10 minutes later a testing lab in a travelling motorhome dedicated to the TdF tests the sample, then discusses the results that evening with a WADA commission that also travels with the TdF. This commission can discuss the findings that evening and release their results by midnight. BOOM.

Why not? Can a scientist please please explain this to me? I mean, if you go to the hospital with an unknown disease, you can have blood work done and results back to you within hours so why not for this situation? WADA’s process includes days and weeks when samples, results and reports are sitting in a fridge, desk, hard drive, envelope, etc. and results in massive delays that lead to this confusion.

In my mind, if you crossed the line as the winner, you won. If you subsequently get found guilty of drug testing you’re banned moving forward. Your wins might have an asterisk, but you won on the road.

We’ve spent years blaming the dopers, but I think a lot of blame should be directed at these massive massive delays and the people who oversee this drawn out process.

This is an obituary, please save wider comments and debate for another day or a different forum.

Right, sorry, my mistake.

Pereiro took 29’57” on Stage 13. It’s always seemed to me he out-Walko’d the great man himself.

People tend to forget that there was a time when it wasn’t that usual to win a GT without getting into breakaways. Walkowiak won in a classic manner. Balmamion or De Mulder won in a similar fashion.

EXACTLY! It sounds like Walko won with multiple breakaways. That doesn’t imply a lucky winner, that indicates he was on excellent form and was paying attention. Opportunistic maybe, but a fluke winner? No way.

Walko said in 2006: “Nowadays it’s impossible to win the way I did. Riders have too much information, and cycling is at the sprinter’s service. That’s why breakawys almost never succeed”.

Very true, you read accounts of his race and he was taking 10 minutes here and there, the time margins involved on each stage were huge. It would have made for odd TV, they could hold a musical interlude between the arrival of each of the top riders on a mountain stage sometimes. Or rather TV and other factors have made racing different. The fact that Bauvin did get so close, at 1m25s on GC in Paris, shows how Walkowiak was challenged to the end.

You’ve reminded me of the Stelviogate day, when Quintana won in Martelltal, and we had to to wait what seemed long minutes for Kelderman to arrive, and it made me feel like “yeah, this is real cycling, waiting forever for the next guy to show up while the clock is still going and mentally calculating the new GC”. It felt really good. Like Chiappucci or Ocaña days. I think those crazy breakaway-packed 1950’s and 60’s GTs would make fantastic watching these days. For the same reasons that a chaotic Paris-Roubaix is a terrific show, only on a 3-week scale.

Very interesting article, Inrng. If I knew how Mr. Walkowiak felt about winning the TdF, I’d have liked to explain that sure, some winners are one-offs like Sastre, Pereiro and yourself. All sports have one-offs or ‘outliers.’

But what makes the TdF more unusual is the ‘law of large numbers’- given that there are 21 days in which to fail or succeed on each day, the best will rise to the top by the end (which explains for the many multiple TdF winners compared with other sports).

And for that reason, Walkowiak can hold his head up high in heaven. Not forgotten.

A gifted and dedicated rider who destiny cheated of his true worth. RIP

RIP Roger Walkowiak. To finish first, first you must finish.

Just goes to show that cycling has always been a cynical sport.

Walko would be the kind of opportunist who would have today’s fans lining up to see his escape try and win over the the clutches of a ‘Sky’ TdF race.

A worthy champion who’s exploits will be fondly remembered.

Nice article but I have a lexical precision. Playwright in english means an author who writes only theatre, doesn’t it ? If so Blondin is not a playwright, he wrote mainly novels more or less autobiographical, like L’Europe buissonnière or Monsieur Jadis (Mister Yesterday, where he tells his most memorable drunk nights).

Blondin, in 1956, compares Le Tour to a bride of a vaudeville : at the beginning he thinks that Walko is the lover, the husband being Darrigade ; at the end he reckons he was wrong, and that Walko is the solid countryman husband who takes the young and pretty bride from all the fops, “a moral ending”, like you quote, even if he’s a little bit ironic, I think.

You’re right, Blondin was more than a playwright, he was a novelist too and perhaps this would have been a better description.

He was even not at all a playwright, he never wrote theatre. But anyway congratulations for your knowledge of french culture, I’m really impressed by your references. Blondin must be very difficult to understand to a non-native speaker, because it’s full of jeux de mots and litterary references.

A playwright can write other things too, not solely for the theatre. Shakespeare for instance, is known for his sonnets as well as his plays, but nobody would seriously dispute whether he was a playwright.

There’s a certain tragic ending of sorts waiting at the end of the career for some professional cyclists. Given the ratio of hundreds of “faceless” riders for every one superstar rider, it’s no surprise that most have a hard time transitioning back to becoming a normal (non-competitive cycling) citizen of society, having suddenly to find a means to make a living to support the family. And for Walko, after the high point of having won a Tour de France, becoming a tourneur must have been a debilitating blow to the ego. And such rise and fall syndromes are common in other professional sports as well. I’ve said it here on this blog before, the UCI or some other sporting union should have in place some support and services for riders–young and old–who are about to leave the profession, such as temporary unemployment funds, career planning and job placement services, retirement funds, health care assistance and insurance, at the least, just like other normal jobs provide their employees–as mandated by most labour laws around the world.

Such support immediately after his retirement might have made all the difference for Walko, and others as well.

There is actually a large fund for retired pros, funded by a 5% levy on all prize money (more at http://inrng.com/2015/12/riders-need-a-stronger-union/) but it’s not something that’s obvious and I suspect a lot of riders who pay in don’t know much, if anything about it.

Yesterday’s L’Equipe had a long piece on Walkowiak, he was never able to cash in on his Tour fame, riding post-Tour criteriums for the flat fee of 1000 francs, about €20 a go in today’s money.

More sad news from the (retired) peloton: Serge Baguet lost his battle with cancer ar 47: http://sporza.be/cm/sporza/wielrennen/1.2885382

He was a rider with stories too, breaking off his pro-carreer for a couple years only to come back and snatch a tour-stage and the Belgium road-title.