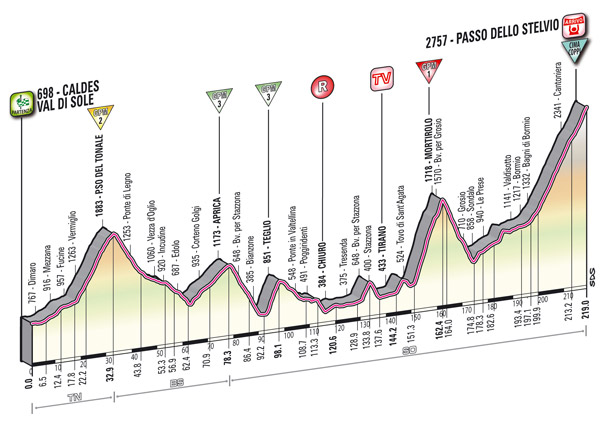

We’ve all seen the cross-section stage profiles used to depict the route of a race. For example here’s the graphic for the Stage 20 of the Giro from Caldes to the finish on the Stelvio, one of the most mountainous days of the season.

These graphics image slices across the countryside to produce a representation of the landscape, to show where the climbs come. But they’re not to scale. If you look at the image above it shows a stage that is 219km long in the horizontal scale but the vertical scale peaks at 2.75km. The Mortirolo looks like a cliff rather than a one-in-ten road. If a stage profile was drawn to scale what would it look like?

![]()

Yes, that is the scale reset to display the 219km length against the actual height of 2.7km. It’s a lot less dramatic but note the Stelvio rising towards the end, it still marks a substantial gain in elevation.

I’m not trying to uncover anything new here. Using different scales for the x and y axes of stage profiles is obvious and useful. These graphics are so universal in cycling that they tell a much better story than the data displayed on to scale. Rather I was just curious to see what the actual profile looked like and the result can be seen above.

Of course the more a stage profile looks impressive, the better the story. The more the stage’s cross section resembles a sawblade, an alligator’s teeth or some other violent or dangerous simile then the more drama for readers to imagine. Data are often be manipulated with graphics to tell a story, to place emphasis. These diagrams emphasise the vertical climbing over the distance travelled.

It can pay to check the actual gradients of the climbs rather than rely on the graphics. This is particularly useful for races away from the major mountains where organisers might want to hype up the climbing involved. But when names like the Mortirolo and Stelvio appear you don’t need graphics as the very names should conjure up images of steep ramps, year round snow and compact chainsets.

Funny, never looked at it this way. Drawn to scale is a lot less impressive to us not pro-riders.

A cousin (an Astronomer by trade) once told me if you scaled the Earth down to the size of a Football (the round ones not the Rugby-ball shaped ones) our atmosphere up to 100 km altitude and all it contains would be represented by a very VERY thin layer of varnish. Makes you realise how insignificant we really are.

Those climbs still seem big though!

If the earth were the size of a marble it would be the smoothest thing you’d ever felt…

Interesting subject. The spectacularity of the profiles is part of the marketing of the race. In this regard, I think the Giro is one step ahead the Tour and Vuelta. I like the perspective they use. But the classic black-and-white Tour profiles (in the 1960’s to 1980’s) were great in their time, and being not as vertical as the ones used nowadays, they set the standard.

I’ve also wondered all my life how climbs could be categorised in a standard, rational way. Swiss races have recently had a tendency to inflate the categories, and Italian races have all their life rated the climbs in an unpredictable, often low-profile fashion, so that inadvertent riders find themselves escalating 3rd category colossus (ask Miguel Induráin if the Valico Santa Cristina, where he lost the 1994 Giro, is really a 3rd category climb). The Teglio, shown in the picture, was actually a bit of a monster, certainly more demanding than the Mende ascent, typically rated 1st category.

The other aspect of the climbs that these profiles don’t show is the number of hairpins involved in the climbs. In the UK it’s not something we really have to deal with but is a major factor in European climbs. I remember Menchov crashing whilst going up around a hairpin during the Sastre Tour and costing some big time.

Yes, this is the other key part of the roads that we don’t always see, the birds-eye views of the hairpins and all the twists and turns involved. I use Google Earth for viewing local roads where I live because I can take a “tour” of the road before I set out to ride it.

Not being familiar with European roads at all, does Google Earth cover these rural, mountainous roads, these infamous, epic climbs? Or are the roads too little-traveled by everyday folks for Google Earth to have them in their system in HD?

Where I live, which is a rural county in CA, the canopy of the trees blocks a good view of what the roads looks like underneath. In other cases, I have fantastic views of a climb before I attempt it with highly-detailed elevation gains.

So many ways to look at a road.

Thanks, INRNG, a very interesting representation of how race organizers “manipulate” the roads in their races. For us fans, the marketing strategies work well. My blood pressure rises and adrenaline starts flowing just looking at these graphics which portray many climbs as “walls!”

But as you say, knowing the gradients brings me back down to Earth and puts these climbs into a more realistic perspective.

Well done!

I remember from the last couple of years that the Tour stages were put into Google Earth 3D, here’s an example: http://bicycling.com/blogs/alloverthemap/2011/06/23/mapping-the-2011-tour-de-france-in-3d/

That gives you a nice birds-eye view of the amount of hairpins involved!

Menchov was constantly having trouble trying to stay upright during that tour…hell, the entire year! If he was on a TT bike you could count on him falling over!

So is it only up to the race organizers to determine the category of a climb, there is no standard or objective way of measuring?

Yes. Thing of the categories and associated points as incentives for the riders. The organisers adjust these to suit. The Giro has some climbs that have no points because they are not “recognised” whilst the Tour can do a climb one year and it’s a first category climb, the next it could be a higher or lower ranking depending on what the organisers want.

This concept is called vertical exaggeration, and is something taught in introductory level geography courses at college and university. My students are always surprised to see the ability of the map-maker to exaggerate features. Always look at the vertical scale, it’s amazing what some of the race profiles in Holland or Denmark can be made to look like.

Heh, I suppose so. Anyway every seasoned roadie will look at the total elevation gain and the distance, and get a rough idea of the climbing effort from that.

I also teach analyzing scale to my biology students. In cases like this, the change in scale is entertaining and definitely dramatic. It is also consistent for the entire profile.

It is when the change in scale occurs during a chart that concerns arise. There was a particularly horrific example in National Geographic where they attempted to show the rebounding of the American Bison and changed scale to allow readers to believe the species was doing quite well. In fact they had changed the scale from 10,000 per marker to 100. Shameful.

Image if the opposite was applied in this case and the Stelvio was a mere speed bump….

Elevation profiles are difficult for a lot of folks to understand. We run into this all the time. Our mountain tours are shown on a 3000 meter scale so the Stelvio will fit, making some of the other climbs look rather small in comparison, whole the others use a 1000 meter scale to give more details. We try to make sure the steepness is represented but it’s still difficult for those with no first-hand knowledge to wrap their heads around, especially when the really steep bits are short…looks easy on paper or a computer screen…but RIDING it is far different. Same with photos…they can only convey so much compared to being there!

Interesting post INRNG,

I have a question about elevation data though. I have always wondered how the max gradient is calculated. Is it over a minimum distance, say 10m? Because if you take it to the extreme, a tiny 1 cm bump could have a gradient on several hundred percent, but it of course wouldn’t be perceived as a hill, just a bump. On the other hand, a perfectly flat 100m section of road that stepped up 10m over 30m could be described as averaging 10%, but clearly that could not do the steep section justice.

Again there are no rules here. RCS, the Giro organisers, seem to quote the maximum number for a short distance. For example in Milan-Sanremo there is mention of an 8% gradient on the Poggio. You sort of know where this is but a few pedal strokes and you’re over it, there is a ramp where you go from 6% to 8% and then to 6%.

This could be a complicated mathematical problem if you really want to capture the maximum gradient.

Mandelbrot mentioned on a cycling website? Nice.

It’s probably not such a complicated thing. Taken to extreme the max gradient will be vertical, a 100% slope. But this is for academia… and the tubs will flex to cope with this gradient.

minor nit: 100% grade is a 45 degree slope (where rise/run = 1)

The shortest meaningful distance would be one bicycle length, or more precisely the distance between the contact patches of the wheels, since those two contact points create the angle of the bicycle itself w.r.t. the horizontal and therefore define the instantaneous effort required for a given ascent rate.

Note that the inside of some hairpins is far steeper than the outside. It’s quite possible for the inside of a curve on a 6% grade to hit 10% or more.

There are no rules, race organisers just quote from lore or by what the riders will perceive.

Would be interesting to review some old Vuelta “preview” profiles with no scale at all! i mean you could have a 200Km stage with the middle of the X axis at 150Km (meaning the last 50 km takes the other 50%:)

think it’s not anymore the case since ASO is involved somewhere in the organization (not sure they’re producing the profile for this race)

I’m interested to know if Grand Tour organisers actually measure the gradient of a climb. If so, do they use differential GPS that can measure elevation to within a few centimetres at closely spaced intervals, or do they use cruder methods that may only give accuracy to within a few metres? I would imagine, in this day and age, the organisers of a Grand Tour would use the most accurate method available. (i.e. differential GPS), to ensure the stage profiles are correct.

That sounds dangerously like innovation, which is banned by the UCI. The race organisers will be consulting a handbook from 1958 which was prepared using only a wine bottle, string, and a mammoth tusk as tradition demands.

Most of these climbs have been surveyed to death, the data is there, it’s all in how it’s presented and classified. The race organizers are running a bike race so they can award points based on whatever qualities they like, it’s the bike fan who gets confused with trying to rate a TdF “beyond category” when compared to a 1st category climb in the Giro. It’s apples and oranges and always will be, even if you ride them yourself. A tough climb on a day you happen to feel strong is often easier than a much lower-rated one if you do it on a day when you don’t feel so strong. The mental factor plays into this far more than most will admit. We learned this years ago, a climb described as brutal causes a certain mental preparation and response, while one that’s merely tough but goes mostly unmentioned often gets the “that was the toughest climb I’ve ever done, why isn’t IT rated as such on the Giro/Tour route?” response.

I think they keep the profiles indicative. Riders get roadbooks that often detail each separate climb but nothing replaces the work done by visiting a climb several times, whether racing over the years or going for a reconnaissance / training camp.

It would be interesting to see all the mountain stages compared with the Y-axis at the same scale, and starting at zero. Even among mountain stages, the scales and amount of the scale truncated is frequently different.

Interesting to see things to scale. Might be a bit cluttered for the marketing man but I’d love to see a basic bit of gradient info on a stage profile next to each climb as it can sometimes take some digging to find the actual figures. Also I assume specific, detailed climb profiles are only produced for the biggest climbs of a race – seems to be a bit hit and miss but I’m assuming the organisers just produce a detailed climb breakdown for what they see as significant rather than putting every climb in detail into the road book?

The profile doesn’t look very daunting when drawn to scale, but looking at this photo of the Stelvio makes it look a bit more fearsome – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Stelvio.jpg

Well, that picture is really nice, and I also already seen and climb that by myself, still it is the “other side” coming from Prad, which they did not ride up at the Giro this year.

Sure but that is nothing compared to next year’s Cima Coppi climb up the Passo dell’Oroduin. http://i.imgur.com/gTAZ2.jpg

Bring it on!!

Very interesting, I’ve been thinking about maps and mapping a bit recently and how different people use them to represent different things and these stage profiles are excellent examples of this.

This post actually sent me in the opposite direction. Thinking about the way the distance on the x-axis doesn’t match the perception we have of events in the mountains. Which, with some fiddling, led me to generate this, with the x-axis adjusted for time. It is a bit rough – it assumes a single cyclist with constant power and no brakes – but it gives a sense of the significance of the major climbs in a big mountain stage.