Raymond Poulidor died in November 2019. With his grandson Mathieu van der Poel in the yellow jersey in the Tour de France, this is a repost of an obituary that appeared here in tribute, in case readers want some background on Poulidor, his time in the sport and what he meant, and perhaps still means, to part of the public in France.

Poulidor was a champion cyclist and made a name for himself as a loveable loser, a moral winner and a dependable emblem of rural France during a period of societal change. His reputation reaches far beyond cycling and there are Poulidors in sport, politics and life.

Born in 1936, the year of the Front Populaire, he was the youngest of four brothers and was raised in rural poverty. “I will never know if my arrival was a happy moment or one of those calamities that happen so often… one more mouth to feed or another pair of arms to work with?” he told a biographer. His parents were métayers, renting farmland paid for with a share of the crop they produced each year. His childhood saw Nazi occupation – aged six he was ferrying grenades to resistance fighters under the cover of fishing trips – and food shortages. But he enjoyed cycling, borrowing his mother’s bike to mimic his brothers who had started racing. He soon bettered them and was winning races across central France as a teenager.

Compulsory military service when he was 20 meant two years in Germany and Algeria he returned 15 kilos heavier and got on the bike again over the winter of 1958-59. He found form by the summer and started a race in Peyrat-le-Château, a short ride from his home. He was up against professionals like Jean Dotto, fourth in the 1954 Tour de France and winner of the 1955 Vuelta a España, and Bernard Gauthier, a former French champion and Bordeaux-Paris winner. Dotto won while Gauthier got lapped several times by Poulidor. Gauthier told his team manager Antoine Magne that he’d discovered a “rare bird”. Magne, a Tour de France winner, had become one of the top team managers and held views on training and recovery that were ahead of his time but he was also enigmatic and superstitious, using a pendulum to dowse the health and talent of his riders (knowingly mocked in a scene of Le Vélo de Ghislain Lambert). Magne and Poulidor shook hands rather than signing a contract and an 18 year career as a professional began. Long by today’s standards, exceptional for that era and it meant he’d race against the likes of Louison Bobet, Jacques Anquetil, Eddy Merckx and Bernard Hinault. No wonder he finished second so often.

Poulidor is famous for being the “Eternal Second”. He still enjoyed victories galore, indeed he won 153 races and finished second 65 times. As a second year pro in 1961 he took Milan-Sanremo with a solo win. He’d go on to win the Vuelta a España, Paris-Nice, the Dauphiné, the French championships, the Flèche Wallonne, the Midi Libre stage race and seven stages in the Tour de France. Yet he didn’t win the Tour de France. It wasn’t for trying, he started 14 times, finished 11 and stood on the podium in Paris eight times, but never the top step. He never wore the yellow jersey either, not even for one a day. He fell short by 0.8 seconds in the 1973 prologue to Joop Zoetemelk, cycling’s other eternal second for his six second places in the Tour.

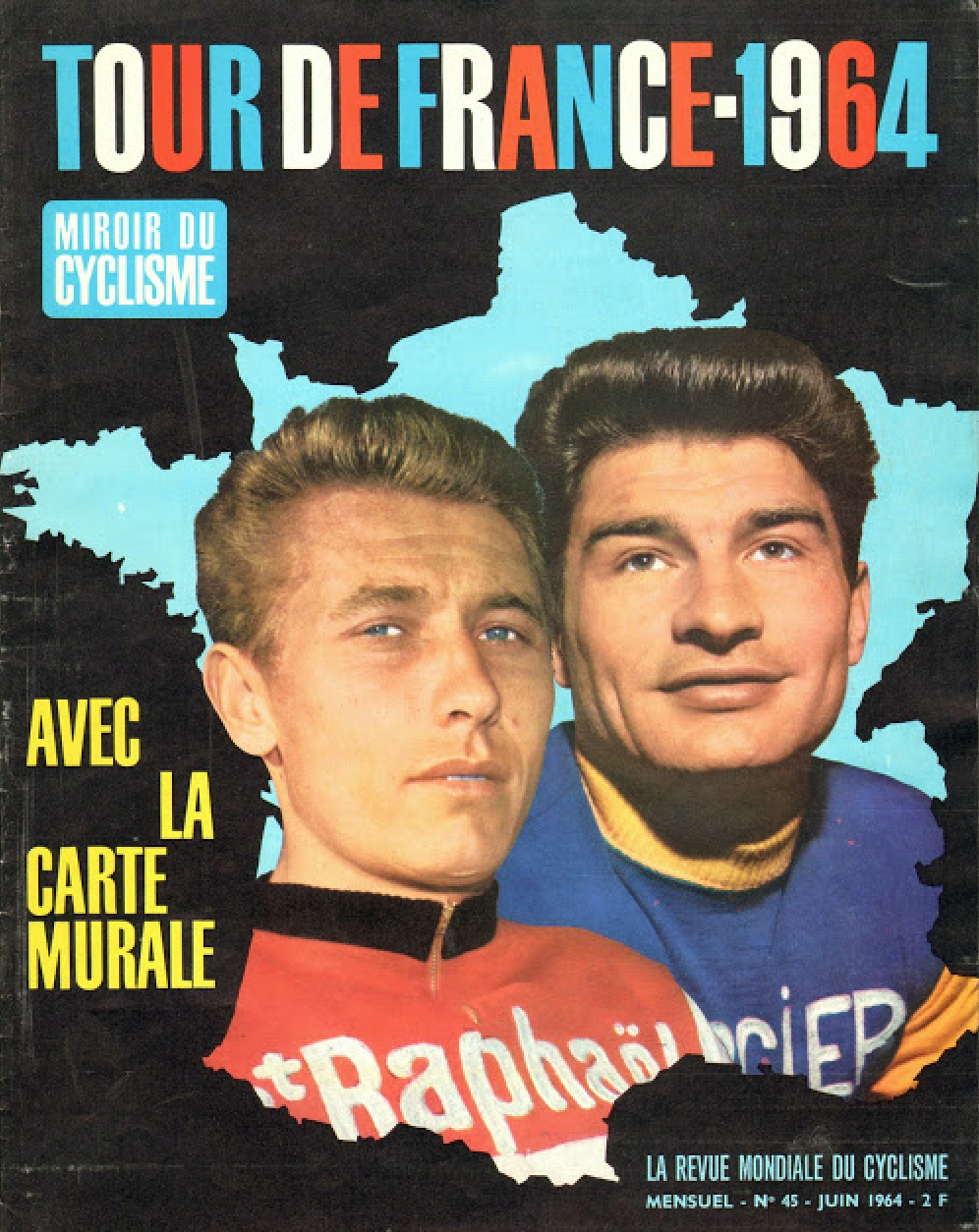

Poulidor turned up for his first Tour de France in 1962 with his hand in plaster and lost eight minutes on the opening stage but still managed to finish third overall which saw him celebrated for his courage, what playwright and sports columnist Antoine Blondin labelled Poupou-larité in a nod to his affectionate nickname. Often unlucky, he sometimes brought misfortune on himself. The 1964 Tour de France makes a good case study. Stage 9 finished on the athletics track in Monaco and Poulidor blundered, sprinting for the line after one lap when they were supposed to complete two, leaving arch rival Jacques Anquetil to pip him and collect the one minute time bonus. Later, on the stage to Toulouse, a puncture and crash caused by his mechanic would cost him more time.

With two stages to Poulidor had made a triumphant comeback in the Pyrenees and Anquetil was leading by only 56 seconds and faltering as he’d done the Giro d’Italia and the final week of the Tour was close to cracking him. The upcoming summit finish on the Puy de Dôme should have been the moment for Poulidor to strike back. But the mountain would be too much.

“I lied to Antonin Magne. He’d asked me to go and check out the Puy de Dôme. I had 42×24, too big. At the stage start in Brive, when he saw Bahamontes had fitted a 25 tooth sprocket, he asked if I’d been to see the climb, yes or no. I didn’t dare tell him the truth. But in those days we had such small salaries and three days before the Tour we rode criteriums.”

– Raymond Poulidor, L’Equipe 8 July 2013

Instead of a recce Poulidor rode a criterium for cash. In today’s context it sounds unforgivably greedy but then riders earned income from criteriums rather than team salaries and his decision was understandable. Locked in combat, the moment was immortalised in that image but Poulidor managed to put 42 seconds into Anquetil but days later lost time in the final stage of the race, a time trial from Versailles to Paris. Did the Monaco mishap, the Tolouse crash and the gearing cost Poulidor the race? To tot up a ledger of gains and losses would be to miss the point: Poulidor looked stronger but lost and became a public hero for it.

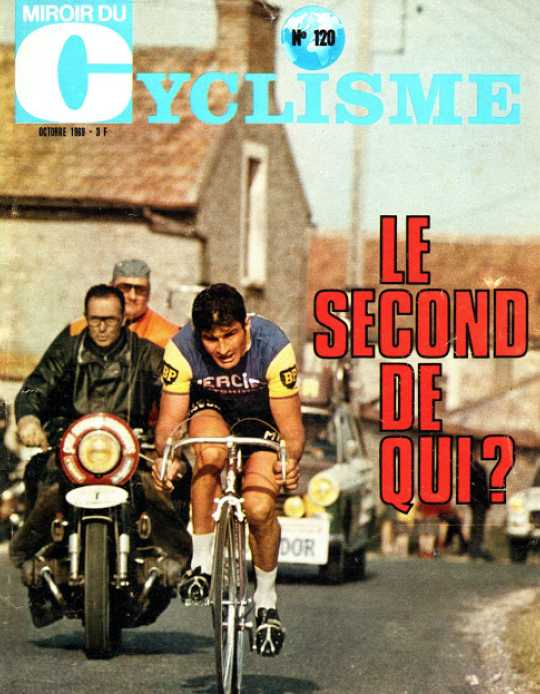

Finishing second was his trademark, Miroir du Cyclisme’s 1969 end of season cover asks who he’d finish second to next year (answer: Eddy Merckx). Poulidor wasn’t a loser, he was often proclaimed the “moral victor” of many races, wildly popular with the crowds who found Jacques Anquetil’s winning ways cold and economical, “like a diner who rushes out of a restaurant without leaving a tip” quipped Blondin. A decade on from Coppi and Bartali, France had Anquetil and Poulidor: a sporting rivalry with an undertone of social change during the Trente Glorieuses. One part of a rapidly modernising France could see themselves in bourgeois Anquetil as he posed in sharp suits and sports cars to a soundtrack of Johnny Hallyday singing America’s Rockin’ Hits. Another part of France preferred the accordion and cherished Poulidor as the valiant and reliable peasant, a product of terroir with his rural accent.

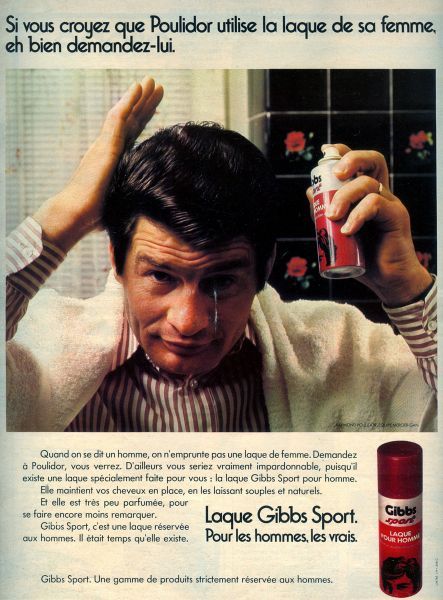

These labels were caricatures. Poulidor might have grown up on a farm but lived in a modern concrete villa rather and drove a Mercedes, not a tractor. He would front ad campaigns for male grooming products. Cyrille Guimard tells in his autobiography that Poulidor was a shrewd investor. Pre-season training camps saw riders pay for their board and in the evenings Poulidor would challenge team mates to a card game and invariably won, accumulating enough cash to pay the hotel bill by the end of the week. Money seemed to motivate Poulidor, for example Eddy Merckx was the full cannibal in the 1972 Paris-Nice, dominating, going for intermediate sprints, tussling for bunch sprints and with one stage to go, in the overall lead too. The prize that year was a motor boat and Merckx was so confident he posed for a photo session with “his” prize on the morning of the final stage. But race organiser Leuillot needed some drama and offered Poulidor 10,000 francs if he won. Poulidor stormed up the Col d’Eze to win the race and deny Merckx.

Later in retirement Poulidor wondered aloud if winning the Tour de France would have ruined things. There’s a book to be written about French attitudes to sport and how a valiant loss is often celebrated more than a calculated win. Arguably a victorious Poulidor would still have been popular because of his humility and rural charm: the model grandfather. Still, to be the perpetual runner-up turned Poulidor from a surname into a noun: Michel Rocard’s failed bids to become President saw him labelled as “the Poulidor of politics” and the term is regularly applied to any runner-up.

When Laurent Fignon climbed in a taxi to be asked “are you the guy who lost the Tour by eight seconds”, he rapidly replied “Non monsieur, I’m the one who won it twice”. Poulidor by contrast would go on TV chat shows to endure gentle mockery from urbane Parisian hosts without the need to bring up Sanremo or the Vuelta. Equally he avoided saying anything controversial or polemic, which helped keep him popular. He enjoyed his status, he even seemed to crave it and spent many years on the Tour de France caravan where the crowd, especially the senior element, loved him and he was an ambassador for the yellow jersey sponsor,and the joke was he was in a yellow shirt. He was like a hit record or a vintage car, people enjoyed the comforting nostalgia he offered. He adored the public too, telling Jean-Paul Ollivier on France-Info radio in 2015 that he couldn’t bear the thought of the day when he walked down the street and people didn’t come up to him. He was feted by the Tour de France with a stage start in his home town of Saint-Léonard-de-Noblat in 2004, and in 2013 the town unveiled a statue of him. If he liked recognition this must have been a joy because it was placed halfway between Poulidor’s house and the town square, the daily trip for a newspaper or baguette meant passing the monument.

Recently he enjoyed a new label. His daughter Corinne married Dutch professional Adri van der Poel and so the Eternal Second became The Grandfather of Mathieu van der Poel to a new generation. He was very proud of this too. Poulidor kept a close eye on the sport and as a guest on Europe 1’s Club Tour radio show in July 2019 proved a sharp pundit with views on Egan Bernal and Julian Alaphilippe that were quickly proved right in the Alps.

Cycling changed everything for Poulidor, “without a bicycle my horizon wouldn’t have been much further than the hedge at the end of the field”. Poulidor’s secret was that he knew this and never lost sight of the fields where he grew up.

an amazing stage to watch and likewise the background and perspective from IR, thanks to the riders and the writer.

Great stuff Mr IR and a splendid epoch. Poulidor came from a generation where to be naturally stocky did not seem incompatible with climbing and winning GTs. Thévenet was a slightly later version from a similar background, looking rugged but expressing himself lucidly and with perception as consultant for France Télévisons. If either had been around today team trainers and doctors would no doubt have had them pared down, but would that have brought better results?

They both have similarities, coming from central France and areas famous for cattle (Limousines for Poulidor, Charolais for Thévenet) and both very nice guys. The build is interesting as you seemed to need a lot of strength back in the days to climb, they didn’t have low gears like today so had to force the pedals over which required huge muscle strength and also back muscles. Poulidor said he used to chop logs in winter as a means to work on his core.

Great write up. Enjoyed the ‘eternal second’ pun in the stage 2 write up too. Very clever.

153 wins and a palmares that would be the envy of any racer. Immortalised in a photo that could define bike racing and the TdF and ‘second’ to the biggest names in cycling who won the TdF 5 times. Amazing story that could be the template of how sport can lift someone from nothing to fame

Raymond Poulidor was an amazing champion who inspired cyclist and cycling fans world wide because of his toughness and never -give- up attitude which was always demonstrated in every race that he participated. He is a legend!!!