The third and final part of the series looking at the 1964 Tour de France is a look at what made it such a good Tour. If you’re in a hurry: it came down to a contest between two riders and was close right until the end… but there’s more to it than that.

A Tour de France doesn’t happen in isolation and there were long term and short term factors that helped set things up for July. France was booming and this made a difference, more could afford time away from the fields or factories to watch the race go by; rising car ownership allowed many to travel to the race, and plenty could now afford a holiday in July.

For those staying at home, television ownership was soaring (from 20% of households in 1961 to 50% by 1966) enabling a new audience to follow the race. More people were able to enjoy this race in new ways.

Jacques Anquetil and Raymond Poulidor were both having excellent seasons and the public was looking forward to the contest long before it started. Poulidor won the Vuelta, then held between April and May. Anquetil had just won the Giro. The Giro-Tour double is a tough task but more so in 1964 when the Giro ended on 7 June and the Tour started just two weeks later. The fatigue probably contributed to Anquetil’s troubles on the climbs in the Tour, this helped to keep the contest close.

The duel aspect plays a big part, it simplified the contest. Imagine if five riders were in with a chance of winning overall come the final time trial? It would be remarkable, uncertain but probably unsatisfying too, especially for the mass audience, as if the preceding three weeks had not been sufficient.

Better still for the Tour, this was a duel between the two best Frenchman in an age when a quarter of the peloton was French and most of media and audience were French. It mattered too, the riders were national figures and household names. Friends, families and workplaces were divided, France was split between anquetilistes and poulidoristes. Not the whole population, let’s not pretend this was the Dreyfus affair, but plenty took sides to the point where history books about France covering the 1960s with no interest in cycling often mention this. Each became a proxy for two different types of France onto which people projected ideas and were wedged apart. Anquetil was modern, efficient, consumerist; Poulidor was traditional, amateur, a son of the soil… or rather they were stereotyped this way much like Fausto Coppi and Gino Bartali a decade before. Many fans nurtured a vested, visceral interest in the outcome of the race.

If Poulidor and Anquetil were caricatured as opposing figures, then their respective team managers really were. Antonin Magne and Raphaël Géminiani were successful professional riders and both came from the Auvergne region of central France but they were very different in character and method.

Magne was an introvert who used the formal vous with his riders. He tried to study the sport, many of his ideas were ahead of their time, “Tonin la méthode” knew the importance of recovery, diet and training methods. He laid on recon rides of major stages. Some methods were eccentric, for example using a divining pendulum to rate riders, where Magne found Poulidor to be an exceptional athlete but with a “negative energy” in June and July.

Géminiani, “Gem” or “grand fusil” (“big gun”) was – or is, he’s in a retirement home these days aged 94 – the son of Italian immigrants fleeing Mussolini and a charismatic rider and manager, often ready with a quote and a sharp one-liner. It was Magne who planned the hour long warm-up ahead of the Andorra ambush, it was “Gem” who saved Anquetil with an alcoholic tonic at the top of the climb.

The route helped make it a good edition, it was something Christian Prudhomme might deploy today with early incursions into the middle mountains of the Vosges and Jura and more frequent use of short stages, albeit in relative terms, as stages under 200km were viewed as short. This made for complaints among the riders of a nervous race run at high speed because the opening week hadn’t already begun to prove much of a hierarchy among the overall contenders but this tension just made things more exciting. The Alps and the Pyrenees were dramatic but not decisive, huge altitudes but the time gaps stayed small.

Time bonuses were big with one minute to the stage winner each day and 30 seconds for second place, and time trials offered 20 seconds and 10 seconds. But this was an era when time gaps from racing were generally bigger too. In the end they didn’t skew the race: Anquetil earned 120 seconds in time bonuses while Poulidor gained 110 seconds. We can wonder what could have been in Monaco with Poulidor sprinting a lap too soon but overall the time bonuses didn’t distort the race as much as you might think, in part because the likes of Federico Bahamontes and Julio Jimenez were banking them in the mountains.

Away from Poulidor and Anquetil, the mountains competition was excellent with Bahamontes and Jimenez contesting the jersey right until the end, even after the Puy-de-Dôme summit finish on Stage 20 the competition is still open until Bahamontes’ team mate takes the points on an early climb to put it out of reach of Jimenez. Both Spaniards enjoyed two stage wins and featured plenty. There were sprints but breakaways often thwarted and the points competition was tight between Ward Sels and eventual winner Jan Janssen. There were fairy tale stories like German rider Rudi Altig taking the yellow jersey the first time the race visits Germany them. Georges Groussard had a long spell in yellow too, he’s all but forgotten now but held the jersey through the Alps and Pyrenees, a surprise factor like Julian Alaphilippe last summer.

If it came down to a duel this contest took time to emerge. Anquetil and Poulidor went into the race as pre-race picks but the first Alpine stage saw Anquetil look ragged on the Galibier, prompting TV commentator to pronounce Poulidor as the main contender.

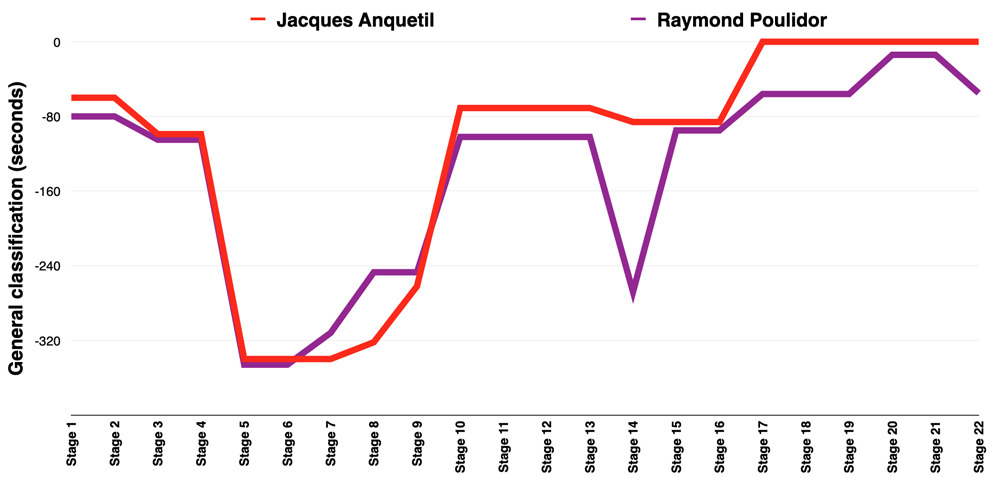

The chart above shows the standings of Anquetil and Poulidor on the overall classification. Poulidor poaches some time after Stage 7 crosses the Jura and a thunderstorm split the race with Anquetil on the receiving end. Stage 9 saw Poulidor bungle the sprint in Monaco so Anquetil collected the time bonus and Anquetil pulls ahead on the Stage 10 TT. Stages 14 and 15 are the big events with Poulidor’s crash on the road to Toulouse and forlorn chase costing him time but the next day he surges clear on the Col du Portillon to win in Luchon and now takes back time. But Anquetil is always ahead on GC and then opens up the gap in Stage 17’s time trial and takes the race lead. Poulidor comes close on the Puy-de-Dôme but can’t seal the deal.

For Poulidor this might have been his best chance to win the Tour de France. The Monaco mix-up saw him gift a one minute time bonus to Anquetil and he lost over two and half minutes on the stage to Toulouse after the bungled bike change and crash. But this was a dynamic race, had Poulidor won the time bonus in Monaco perhaps he would have been marked more closely? If he hadn’t lost so much time to Toulouse, would anyone have left him attack on the Col du Portillon the following day, and would he have attacked as hard if he hadn’t suffered the reversal the day before?

Too many questions and impossible answers but as Anquetil mocked atop the Puy-de-Dôme if he had 14 seconds on Poulidor it was “13 seconds too much”, he was calculating his race on Poulidor. As long as he was ahead he would race all the way to Paris with the final time trial stage like a card up his sleeve. These what-ifs contribute to Poulidor’s popularity, people saw someone who could win if only he could get a lucky break.

What might be more true though is that Poulidor lost this race. He had chances to win it but didn’t take them. Both Julio Jimenez and Federico Bahamontes approached Poulidor and his team before the Puy-de-Dôme showdown according to ex-pro Hubert Fraisseix (translation):

“The evening before Bahamontes and Jimenez asked for 5,000 francs each to let “Poupou” [Poulidor] win. Magne never wanted to pay. In the end they finished ahead of Raymond who, with the one minute time bonus for the stage winner, would have won the Tour de France”

Fraisseix is no gossip merchant looking to stir, he was a friend and near-neighbour of Poulidor and perhaps the payment would have helped. Poulidor also confessed to another mistake in the pages of L’Equipe in 2013, he’d gone to ride a criterium rather than recce the climb (translation):

“I lied to Antonin Magne. He’d asked me to go and check out the Puy de Dôme. I had 42×24, too big. At the stage start in Brive, when he saw Bahamontes had fitted a 25 tooth sprocket, he asked if I’d been to see the climb, yes or no. I didn’t dare tell him the truth. But in those days we had such small salaries and three days before the Tour we rode criteriums.”

So instead of a reconnaissance for the climb as Magne wanted, Poulidor rode a criterium to earn some cash. It sounds greedy and foolhardy today but should be judged in the context of the time when criteriums formed the staple earnings provider for pros, but it’s still another mistake and makes Poulidor look at least the co-author of some of his misfortunes.

Conclusion

A vintage edition with the winner unknown until about 1,500m to go and the closest winning margin. Like other celebrated editions, the reduction to two riders helped make it a famous contest and a slim margin kept the suspense to the end.

There was plenty of sporting drama along the way with both Anquetil and Poulidor suffering setbacks and then reversing the situation and in the end the inevitable result of Anquetil winning again and Poulidor losing despite his best efforts, each conforming to the stereotype but only at the conclusion.

More than this, it happened an era when the Tour de France was reaching new audiences and involved two protagonists whose popularity reached well beyond cycling.

- Finally that photo of Anquetil and Poulidor going shoulder to shoulder on the Puy-de-Dôme has its own short story. It was taken by Roger Krieger of L’Equipe. “Krikri” was a regular on the Tour in the 1960s and would shoot from the back of a motorbike. As Poulidor and Anquetil rode side by side, the photographers were desperate to shot the moment but on the 10% slopes the racing was slow and the motorbikes clumsy. Two touch, one veers sideways towards Poulidor and its exhaust pipe sears his leg and he flicks right, bumps into Anquetil and in the split second Krieger takes the photo that encapsulated up the race… even if an exhaust pipe was really to blame. Oddly the negative has gone missing, copies today are reproductions of the photograph.

1964 Tour de France – Part I to set the scene

1964 Tour de France – Part II a stage-by-stage account of the race

1964 Tour de France – Part III a review of what made it so good

Great stuff (as usual)! Thanks for posting this. Another good account can be found here: https://bikeraceinfo.com/tdf/tdf1964.html

Vive Le France!

Thanks, I’ve really enjoyed this series, and the comments, too. One minor typo, I think you mean “…seal the deal” at the end of the tenth paragraph.

Fixed that, thanks.

“Poulidor won the Vuelta, the held between April and May”. Even more minor I think you mean then held.

Cheers and thanks for the piece. Interesting and well written.

And was it still (just) a two-week race in those days?

It can’t be any less than a three week race with 22 stages. Dates are on the graphic above though.

Yes, the Vuelta was typically two and a half weeks in the 1960s, in 1964 it ran from 30 April-16 May.

Such a good series and as a bonus the story behind that picture on the Puy de Dome.Fine writing and I’m hoping you may dig up a few more epics .Thankyou.

Thanks very much: a superb series and a great read.

Ha, Race motors are a nuisance even back then.

Thanks for the great series

I love history in general and your stories of cycling history are absolutely fantastic. Thank you so much.

The picture in a fuller frame is here:

https://www.yellowkorner.com/gb-en/p/jacques-anquetil-raymond-poulidor-1964/467.html

It looks like a RTF and press motorcycles may have been the ones that touched?

And if the photographer was in front of the cyclists, that’s an incredibly close box-like surround almost. The noise and pollution from the motorcycles must have been something.

I’ve often thought that ‘vintage’ cycling photographs commonly show the cyclists with filthy faces after a stage, even on a sunny day. Whether this was from the exhaust emissions of the cars and motorcycles, I’m not sure?

I guess the hidden benefit is that there is no room at all for idiot runners in fancy dress to get in the way…

It could also be the cylinder head from the motorbike than touched Poulidor?

As you say, a lot of bikes. There’s a good quote from L’Equipe in the 1970s that “le parfum de gloire et d’abord celui des pots d’échappement”, bluntly “glory smells of exhaust pipes”.

When you blow the fuller picture up, each motorcycle has a sort of skirt cover around the engine block but it doesn’t appear to give total protection.

That’s a great quote also. No unleaded petrol back then.