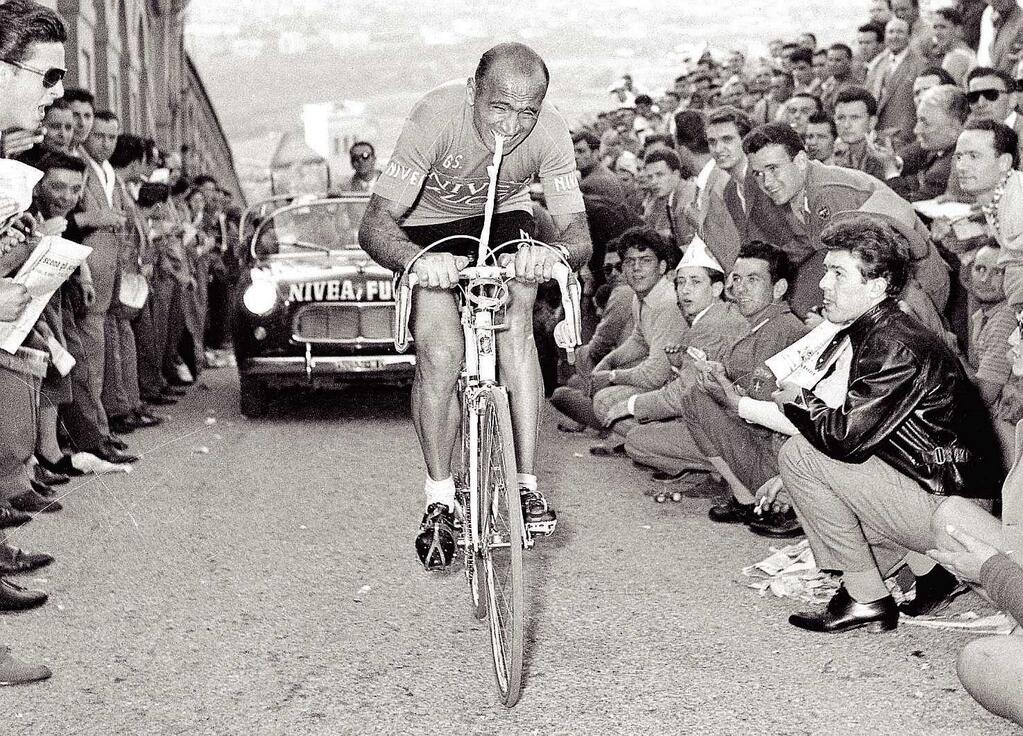

Look at the picture above from 1956 Giro d’Italia and what do you see? Fiorenzo Magni climbing with something strange going on between his mouth and the bike. You see the crowds and we can even identify the place as the climb to the San Luca in Bologna thanks to the arches of the portico, today’s finish of the Giro d’Italia stage. But this blog post is about another detail, that of the Nivea brand featured on Magni’s clothing and the following car because Magni and Nivea gave us the business model for cycling today.

As for the contraption, in case you didn’t know Magni crashed on the previous day’s stage of the Giro and broke either his shoulder or his collarbone, reports vary. He wanted to finish but his injuries meant he struggled to pull on the handlebars, an essential part of cycling in the days when riders only had a few gears on their bike and climbed in a slow cadence, rocking their shoulders left and right in order to use as much muscular force on every pedal stroke. Magni’s mechanic came up with the idea of using tying an inner tube onto the bars which Magni could then bite onto as means to keep him bent over the bike. It worked but whether it helped must be debatable, after all if you’re chomping on an inner tube then breathing must be hard. Somehow Magni went on to finish second overall.

Now onto those Nivea logos. The standard model for cycling teams was to be sponsored by a bicycle manufacturer. Right from the start of the sport, manufacturers have been central to the sport and if many races owe their existence to newspaper publicity stunts, the cycle industry also played a big part in the early 20th century. Bikes were an important mode of transport in Europe for workers looking to commute to the field or factory and what better way to market a machine’s reliability than proving it can be ridden from Paris to Rouen or Milan to Sanremo? Today we see Paris-Roubaix as a big shop window but this is for a very small niche of the market – people who buy suspension road bikes for sport – but in the early 20th century cycling brands were sold to the mass market. In Italy there were teams like Fuchs, Atala, Bianchi, Legnano, Bottechia, Benotto, Torpado, Ursus, Wilier Triestina and more, all bike brands.

Only things were changing in the 1950s. A motor car was still prohibitively expensive for most but it was becoming more and more affordable as wages rose and production costs fell. Italy in particular saw a boom in small motorcycles, notably by Piaggio’s Vespa (“wasp” in Italian). After World War Two Italy had a lot of manufacturing capacity that had been directed at the war effort looking for a new market and Piaggio switched from aircraft to scooters. Sales boomed and presumably many were substituting their bicycles for Vespas.

Either way, the short version is that one day Fiorenzo Magni heard from his team’s sponsor, the bicycle company Fuchs, that they couldn’t support the team any more. Magni’s first response was to change teams but if other managers were interested in him, after all he’d won the Giro twice already and the Tour of Flanders, they said they could take Magni but not his colleagues. In 1953 Magni then hit on the idea of getting a sponsor in and helped by a friend who worked in pharmaceuticals, approached Nivea, a Germany company today famous for its cosmetics and so not the obvious partner for Magni and his rough looks but back then they made soap and other products more associated with life on the road. Magni visited their offices in Milan and the manager, a Swiss man called Zimmerman as he recounts in his autobiography (translated):

“I explained our needs to Signor Zimmermann he was very interested and we immediately got onto the subject of money: the team, cut to the bone, would have cost 20 million [lira], of which five was my salary. I was the team leader, sports director and owner of the company, and all at my own risk. My career as an entrepreneur began this way. The other 15 million were used to honor all the commitments, for travel and hotels at races, in addition to the salaries of the seven teammates and staff, reduced to the minimum: a mechanic and a masseur, one following car, all to save money.”

Eight riders is leaner than the format we’re used to today. But having a sponsor from outside the sport fund a team in exchange for their name on the jersey was game-changing and it was all down to Magni and necessity. Within a few years other corporate sponsors came into the sport like Faema (coffee machines), Ignis (refrigerators) and drinks company Saint Raphael, the original “Rapha”.

It wasn’t an overnight change. The Tour de France refused to host these outside sponsors but there was a way around. Saint Raphaël, was, and still is, a a drink that was part tonic, part apéritif. First created in 1830, Saint Raphaël joined Coca Cola and mineral water as something that went from a pharmaceutical product to a booming consumer product. But it was blocked from the Tour de France so they renamed the team “Rapha-Géminiani” to pretend there was no commercial link, that the team was simply named after the team’s directeur sportif, Raphaël Géminiani. But this was a ruse, the directeur sportif‘s first name just coincided with the sponsor, the funding was coming from the beverage company and they rode in kit that matched the branding. Soon the Tour de France relented and ever since we’ve associated cycling teams with corporate sponsorship.

Since then there have been few changes. In the 1980s Laurent Fignon and Cyrille Guimard swapped car manufacturer Renault for supermarket group Système-U but with a difference. Renault, like any other pro team, belonged to its sponsors. Fignon and Guimard created a company that recruited the rider and effectively sold the naming rights to a main sponsor and this is typical of today’s teams. Today the likes of Movistar, Bora-Hansgrohe and others are effectively marketing companies who have inked deals for naming rights but some sponsors do own the team outright, like Ineos and EF Education First.

Conclusion

Magni’s genius was to embrace the consumer changes around him as Italy swapped bicycles for Vespas and consumer brands took off aided by mass communication and advertising. There’s a chorus from some quarters today that cycling’s sponsorship model is broken, although this sits at odds with the record sums of money coming into the sport. World Tour team budgets and rider wages have never been higher, there are more teams in the other tiers and Women’s cycling is growing fastest of all. Still, cycling’s sponsorship model is old, consumer brands rely on more sophisticated marketing than you or I seeing someone sporting a logo on a jersey; and the age of mass television seems at a crossroads although live sport is still valuable to broadcasters and explains why the Tour de France shows every stage live from start to finish, something this year’s Giro is going to with nine stages this year.

But Italy gives us a clue to because while Magni’s example was imitated by countless Italian teams backed by consumer brands, this trend has regressed almost back to the start as today all the big Italian teams are gone and only one Italian brand is left in the World Tour, coffee company Segafredo. Magni opened the door to sponsors but they’re gently walking away out to be replaced by wealthy billionaires and quasi-governmental sponsors in search of legitimacy.

Another fascinating slice of cycling history, with lots of intriguing tangents. Bravo!

I’ve recently been nursing an injured shoulder (apparently capsular inflammation, though I first thought it a separated shoulder), and I can attest to the reality that it doesn’t bother me to ride a road bike except when I stand on the pedals and pull on the bars to surge up over a little Dutch canal bridge or inject a burst of speed into my usually steady rides. Here in Holland it’s not enough of an issue to keep me from riding, but I can only admire Magni’s ability to tolerate pain, given the inclines he was facing.

Parenthetically I’ll note that saying it was either a clavicle or shoulder issue is slightly redundant, since the collarbone is a significant part of the shoulder. I’ll also note that the pain that comes with my injury is excruciating with certain movements (abduction primarily), so I can barely take off my own coat, but doesn’t bother me at all with other movements (I can still do bench presses).

Anyway, I always enjoy these historical perspectives. Too many people look at the short run, in cycling and elsewhere, and imagine that very recent history tells more of a story than it does.

Great stuff! As to: “… but they’re gently walking away out to be replaced by wealthy billionaires and quasi-governmental sponsors in search of legitimacy.” most here well know my opinion about how and why this has come-to-be, so I won’t write anymore than this reminder.

Some might not know Fiorenzo Magni was the force behind the Museo Ghisallo https://www.colnago.com/en/news-en/ghisallo-the-bust-of-fiorenzo-magni-unveiled/

Don’t miss this if you are ever anywhere near Como!

Fascinating stuff, thanks.

Great story.

But one minor correction

” approached Nivea, a Germany company ”

Nivea is just a brand name, the company was and is the Beiersdorf AG, famous also for other household brand names like Tesa and Hansaplast

I think you could be right but wasn’t sure, the history of WW2 means the company was broken up and various international versions of Nivea appeared around the world which Beiersdorf eventually acquired again. The war affected other things in this story, Magni’s record during this time wasn’t covered but it’s covered elsewhere. John Foot’s Pedalare! Pedalare! is a good read on Italy’s cycling history.

Now that I read the English Wikipedia page, which is far more detailed than the German one (which seems odd), I see the situation was complicated. But I’m sure Nivea was never a own company.

Nevertheless, though I know some cycling history, I never thought that Nivea was the first outside sponsor.

I can only remember the first brand name on German soccer jerseys, Jägermeister.

+1 on the Pedalare! Pedalare! suggestion. While I’m at it I’ll plug my friend Bill McGann’s Giro history as a good historical account and Herbie Sykes’ Maglia Rosa as perhaps my favorite of them all?

Didn’t Magni fight for the fascists in the war? I vaguely remember hearing something about a “third Italian great” but history had forgotten them due to being on the wrong side.

Fascinating article!

Love this article.

I’m an ex-rider and still an enthusiast of Italian vintage motor scooters.

The model pictured is a 1958 Vespa 125cc vna12, I think.

The launch price of a 1956 Vespa 150 was 148,000 lira – around $240 at the time, or about two – three weeks’ wages for a skilled male maintenance worker in the US.

I’m sure the average weekly wage in Italy was considerably less than this but, nevertheless, the scooter was still an affordable means of travel, especially for the younger generation.

Around the time that professional cycling was allying to commercial partners, the Italian motor scooter manufacturers were promoting a more glamorous and upwardly-mobile lifestyle with film and pop stars associated with their machines. The 1963 release of the Lambretta Li150 Special in the UK was sold as “the Pacemaker “ after the beat group Gerry and the Pacemakers –

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=q5C2xV8nhJs

I like these old things too….right up to the point the local Vespa/Lambretta club passes on a Sunday while I’m out there cycling. Then, cough…cough…..not so much. It’ll be a great day when 2-stroke engines are museum pieces only. The old Fiat 500’s don’t pump out nearly as much choking exhaust, so my enthusiasm for them is unconditional 🙂

I love the smell of racing oil in the morning 😀

You’re right though, the two stroke engine is no longer being produced (India still has the old Lambretta works) and many cities restrict them, including Genoa, the birthplace of Enrico Piaggio, the founder of Vespa.

Thanks, Inrng, for another entertaining, cycling history lesson. If you will, though, let me split a hair: as for the purpose and arrangement of the “contraption,” rather than having anything to do with keeping Magni bent over the bike, my hunch is the inner tube was tied onto the bars simply to place it within easy reach whenever Magni’s natural, pain-managing instinct to bite down/stringere i denti arose (and surely it did with a broken whatever). I doubt Magni chomped on the inner tube for the duration of the 3 km time trial and fumbling around in a back pocket for an orthotic device of any kind with his one good arm wouldn’t have been practical.

By the way, “Nivea Soft,” a product I first came across several years ago not far from Bologna, has become my g0-to chamois cream. Good stuff and available worldwide.

I seriously doubt Magni had a broken bone (esp. clavicle), since the risk of dramatically worsening the injury, and the pain with virtually any arm movement, would have been too great. The should joint is incredibly complex, and there are dozens of ways it can be injured. The pain related to each of these injuries can be very specific, as I’m personally experiencing, and having the inner tube the way he seems to be using it in the photo (note how short it is, and how taut it’s pulled) would be like using a cane to take some weight off an injured, painful foot.

Thanks inrng, great article. How does pro cycling compare to F1 in terms of division of monies. I’m struck by the parallels of early motor racing and cycling where manufacturers were looking to showcase the strength and durability of their brands. They both then took on wider sponsorship. Is the key difference that f1 teams share the tv rights revenue?

Formula 1 has big TV rights, cycling doesn’t with many races having to pay broadcasters to film their events rather than naming their price. If they shared the money in cycling it wouldn’t make a difference, see http://inrng.com/2019/01/revenue-sharing-revisited/ where even using wild assumptions to inflate the amounts teams could get the sums involved per team look small.

Excellent story.

Nice! A full slice of cycling history served up with double cream and coffee. Thanks Inrng.