Monte Zoncolan awaits the riders in the Giro. Climbs like the Stelvio, Galibier and others have rich history but Monte Zoncolan’s as new as you get. Although it had been climbed before from Sutrio it was only in 2007 that the road from Ovaro was used with its infamous gradients.

Monte Zoncolan awaits the riders in the Giro. Climbs like the Stelvio, Galibier and others have rich history but Monte Zoncolan’s as new as you get. Although it had been climbed before from Sutrio it was only in 2007 that the road from Ovaro was used with its infamous gradients.

But what makes a climb tough? The steeper the slope the more the contest is reduced to a rider’s power to weight ratio, stripping out tactics, roadcraft and everything else that makes road racing such a subtle contest.

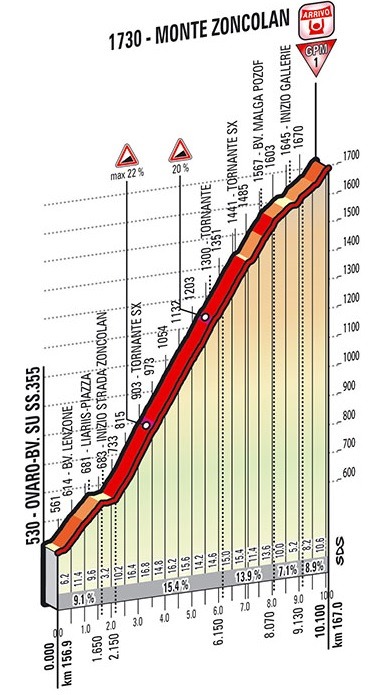

How steep is Zoncolan? In quantitative terms it is 10.1km at an average of 11.9%. Hard enough on these numbers but it includes a few flat portions which means other sections are at 15%,18%, 20% and even 22%.

In qualitative terms, it’s steep enough for mechanics to follow riders on motorbikes for fear a car could stall on the way up. It’s so steep it’s become a benchmark, when a new climb is added to the Giro the reflex is to compare it and a new climb with steep roads might be billed “the new Zoncolan”.

In cycling we talk of climbing but this is not the technical ascension of a cliff face where each foothold must be assured, where falling rocks and crashing ice endanger lives. As tough as the climbs might be, they are merely roads. Gearing solves everything.

Shimano Acera, the entry level mountain bike groupset from the Japanese manufacturer has a triple chainset where the inner chainring has 22 teeth and a cassette for the rear wheel with 34 teeth. For all the hype about the Zoncolan most healthy people could make it up to the top, it’s only a matter of time. It’d be hard on a hot day too.

For the Giro the gear ratios are different but performance is all about a different kind of ratio: power to weight. Aerodynamics barely matter, almost all the power produced by a rider is going to fight gravity rather than air resistance. The power a rider produces is divided by their weight and this ratio is by far the greatest determinant of climbing speed. A fearsome mountain is reduced to the expression of W/Kg.

You can measure a rider’s power output in a lab with on an indoor bike and if you take their bodyweight and the weight of their bike and clothing then you should be able to get the precise power/weight ratio. Put all of the Giro’s riders through this lab test and you could rank their ratios. The result on a very steep slope should be the same. Seen this way even the most fearsome climb is a replica of sterile laboratory.

But luckily it’s not a lab and humans are prone to error. What makes the Zoncolan so important is that a rider has to determine if they can follow their rivals. If they find a rival has a superior W/kg ratio then they risk cracking and consequently losing a lot of time. Each rider will be playing aerobic poker, trying to follow and perhaps set the pace all while bluffing whether they’re in the red or not. This is a much more measured contest. There are few big attacks, just changes in pace.

On such a steep riders rarely need to attack as the strongest will just find the others fade away, unless someone tries to follow another rider and goes into the red, in which case they’ll blow. It’s here that the steep climb can open up big gaps because if a rider gets into trouble there is no moment to recover, they might force themselves to hold a wheel but this risk can backfire if they crack. To avoid this a rider needs only to look at their power meter display on their handlebars and ride to the numbers, using gearing to keep the legs turning like a metronome to a pre-set rhythm.

No lab

The Zoncolan and others can be so reductive that we lose tactics, attacks and the chance for a suffering rider to cling on by bluffing. But thankfully we keep the woodland, the rough roads and the scenery, it’s what makes the race and why nobody would watch a lab test live on TV. One reason the climbs attract such big crowds is because the riders pass by so slowly that spectators can see the pain.

Conclusion

The sport loves to hype up the difficulty of a climb like the Zoncolan and it’s true, it’s unmissable TV because it’s so hard. But the steeper the climb, the more it is reduced to a contest between power and weight, especially with today’s choice of gearing. Tactics, following the right wheel and other matters have a lesser role, for example there’s no point sending a team mate up the road to act as a relay to pace their leader on the slope. It hurts but a steep climb is a simpler test than we might imagine and one we could almost replicate in a lab or gym. The steepest climbs can be better explained by sports scientists than winged angels or mountain gods.

I’ve ridden most of the Grand Tour climbs, but this was the toughest by far, it’s not the steepest, or the longest, just a deadly combination of the two.

Have you tried Col de L’Iseran? It’s never too steep but the plain fact is you’re riding uphill for 30 miles. Plus, at nearly 2,800m, altitude exacts a very real impact on breathing, a factor the article doesn’t take into account.

Yes – climbed the L’Iseran, it’s ‘normal’, the Zoncolan is not normal….to coin a phrase…

Sierra Nevada?

+1. A real beast (even from Sutrio). Haven’t tried the Angliru though.

Same here. My last time up the Mortirolo I swore I would never do it again. I can say the same for this one, though getting up to the 200 meter mark and settling into the “stadium” to await the race was an experience I’ll savor forever. I’ll have my own blog post in a couple of installments once I’ve had a chance to sort through the photos, etc.

Ok-

when do they take this mountain on???

As you describe, a climb such as this is a bit like a time trial or lab test, but with two crucial differences. First, we get see who is strongest in real time, with the riders lined up side by side and nowhere to hide. Second, whereas time trialists are hidden beneath ridiculous helmets, hunched over and whiz past at 50+ kph, on a mountain you can see up close the strangely mesmerizing sight of athletes pushing themselves right to the very limit of their abilities.

” spectators can see the pain”

That is why I’ll be watching

if i’m not wrong, contador said the zoncolan was the hardest mountain he had ever climbed back in 2011.

You talk of cars stalling, one of your pictures show the time in 2010(?) a TV moto gave up the ghost. To maintain that low speed you need sustained high revs and a constant feathered clutch. Not good for a bike.

True, but a broken motorbike won’t block the entire road.

BMC’s VW Transporter croaked right in front of us. The stench of smoked clutches was pretty thick all day. Eventually the BMC van was pushed back to a switchback turn where it no longer blocked the road, where it continued to smolder and stink pretty much the rest of the afternoon.

Ban power meters to make to make it more of a test, riders will have to make more decisions rather than just look at the numbers

Riders get good at pacing, the power meter is useful but once riders have been used to pacing they can probably do it without looking at the screen too often. Besides if you know your W/kg you can predict the speed and so a simple bike computer could be used, eg to aim for 15.5km/h on one section, 13.0km/h on another etc.

But they can make mistakes. Especially under competitive stress, the less information they have (and the less precise), the more probability of mistakes, and the more psychology will matter. And who says ban power meters also says ban simple bike computers.

Would anybody else like to see a Grand Tour built forcing differentials to be made on stages like we saw in this year’s Paris-Nice? Nothing reduced to the W/kg formula.

Would riders hate it? There would be no control, no order established.

Yes… or if not a whole race reliant on it we could see more use of the medium mountains, for example the Appenines or the Massif Central in France. But these are often deserted places and it’s hard to get a crowd and the funding for the stage finish compared to a classic ski resort.

Interesting point. This kind of courses should be tried. But in the end, it shouldn’t be one or the other: the idea should be that those who lose time in uphill finishes are compelled to gain it on other terrains. But it just seem to happen. I love medium-mountain stages, but dominant teams seem able to control them and to force a bunch finish if they need to (saw last L-B-L?). This year’s TdF has quite a bit of it, let’s see what happens there. It also used to be the Vuelta’s trademark (before it moved to the Angliru concept), but many consider it a dated concept.

“It just doesn0t seem to happen” (EDIT)

One element of unpredictability: nutso and drunk cycling fans, with no security presence I could discern. At climbing speeds, they can get much too intrusive. Bongiorno got a little more “help” than he wanted today.

Really sad thing happens today. When good intention turns to a bad action.

To be honest Bongiorno seems to me is near to crack any time on the 4 last kms. But it is just speculation of mine.

It depends of nature of each one but standing for bikers on the road to me is shouting some words of encouragement on safe distance, writing names on the ground and so on. But jumping off in front of the rider, wraping up on big flags, running to close of rider or motos is tremendous recipe for eventual disaster.

Maybe the “security” presence was inadequate, but did you notice the army (really, the Alpini) and the Civil Protection workers further up? At some point the organizers have to trust that not too many nutjobs will affect the race, there’s simply no way to keep everyone back. But that’s what makes cycling special compared to so many sports where you might as well watch on TV since you as a fan are kept so far away.

We rode it just yesterday and it’s VERY, VERY hard indeed. Pure suffering and pain, no matter how you do it or what gear you use you’ll suffer all the way from “la porta dell’ inferno” to the top.

I can call a couple more climbs that are as hard as Zoncolan, one is near home (Serra do Paiol 7.3km with 17% avg and many 24-26% stretches). And the other is the climb to Portillo in Chile, not too steep for the most parts but it’s over 50km long at 3000m abobe sea level. And it tilts up at the “caracoles” near the end.

A few remarks:

1 W/kg is not the same for the same rider every day. I would say the standard deviation is not far from the difference between the means of the top riders.

2 W/kg is not the same for the same rider in a lab test as it is at the end of a grand tour.

3 Legends are made on days that a rider manages to push his body beyond the effort he could ever produce in a lab. I’ve read a couple of scientific papers on cycling and often you find the phrase ‘to exhaustion’ to describe for how long a certain effort has to be sustained in the protocol. The definition of exhaustion is very different if a stage or even tour win is on the line.

3 Psychology matters. Even if you know you are supposed to be able to keep up some wattage it will feel different when you’re dropping your rivals than when they are dropping you.

4 If they would (could? didn’t bother to look up the map) put the Zoncolan as penultimate climb in a stage with another climb just after suddenly the tactics aspect is back. A climber can gain more time per m of elevation on a steep hill than an 8%ish affair but will have to balance this against missing out on drafting on the descent and part of the final hill. Team tactics then come into play again as well.

+1.

On point 4: they can, and I wonder why it hasn’t been tried yet.

And W/kg is also not the same after 170km than after 270km.

+1 on points 3 and the other point 3 :).

I know a sports scientist who thinks the head, along with other “governor” functions, make a significant difference to performance. E.g., lab performance tests need to control for the presence of women when testing male athletes, as males tend to perform a little better if women are there than not. 🙂

Oh yeah, and even 22-36 is available. It’s not exotic or anything, standard on some entry (and advanced!) level mountain bikes as well.

this one is near impossible to climb even with 22-34:

http://zigak.wordpress.com/2008/12/11/scanuppia-from-bessenello/