Amongst the Spring classics Milan-Sanremo is the odd one out. For a start the name is genuine. Paris-Roubaix no longer starts in Paris and Liège-Basgtogne-Liège finishes in a place called Ans. The Italian race starts right in the heart of Milan, in between the Parco Sempione and the giant Gothic cathedral.

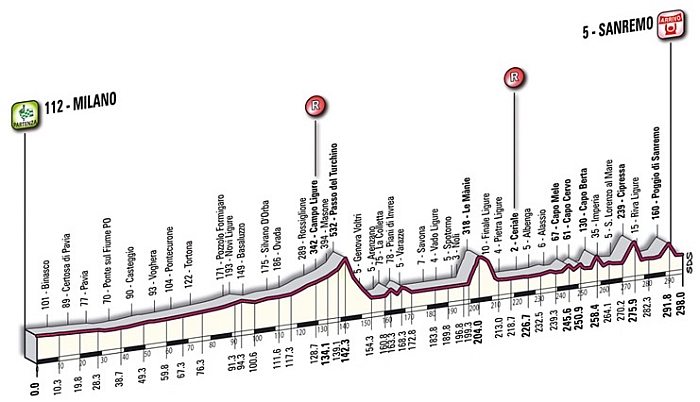

This is also the longest one-day race on the pro calendar. So long that the event has special dispensation to exceed the UCI maximum distance of 250km. Much of the route is flat but it’s fast and every pedal stroke is like a cent or penny borrowed, each one is added up with an interest rate that’s compounded over the seven hours.

Sometimes you can glance at a race profile in five seconds but this route is so long that it’s full of stories, statues, views, food and more. Let’s take a more detailed look at the route via ten photos.

The race rolls out of Milan along large roads and crosses the vast Po valley and the Pianura Padana. Normally you associate rice growing with China or Thailand but these flat plains are engineered with channels and bank, a grid of rice fields that are the start of every risotto dish.

It’s often cold and damp at the start, fog is common in winter and many riders wear thermal gear for this section. In the summer the rice fields are flooded and the evening breeze brings humid and brings mosquitoes. Onwards and the road rises a little as it passes Novi Ligure, the town where a young Fausto Coppi worked as a butcher’s delivery boy and met team manager Biagio Cavanna, changing Italian sport forever. A cycling museum, one of several in Italy, is dedicated to Fausto Coppi.

Onwards and the terrain starts to change, vineyards are spotted on the nearby slopes. Ovada is the town marks the big change in terrain and sits at the start of the long Passo del Turchino. This mountain pass used to be important to the race but it’s a slow and gradual climb, the road is tracked most of the way by the railway line, a clue that the gradient is no worry.

There’s a different feel as the road climbs up this pass. Literally as the March air has a chill when the race gains in altitude but also because there’s an antiquated vibe to this part of the race, of place excluded from the prosperity of Milan and the warmth of the coast. Abandoned mills tell of an industrious past. Traffic roars on the autostrada but the original road, used by the race, is quiet and the sight of riders in their bright kits and shiny bikes must be the most exciting event of the year.

Turchino means blue, a rare word a bit like azur in French and it’s just like the Mediterranean sea that awaits on the other side. The pass is a symbolic moment, lifting riders away from the foggy plains towards the shimmering spectacle of the Mediterranean, from a landscape defined by soil and toil to another lined with beaches and farniente. Right at the top of the pass there’s short tunnel and you almost change season, going from wintry inland terrain to the softer maritime climate in 170 metres.

It’s here that the racing gets even more serious as the riders drop down to skirt Genoa, the port city with its shipyards and heavy industry, escaping along the Via Aurelia, the coastal road that’s at times cut into the cliff. The race passes through Savona, another port which has hosted stages of the Giro over the years. Mark Cavendish won last summer, there was high drama in 1969 Eddy Merckx was thrown off the race after testing positive for a stimulant.

The pace picks up well ahead of Le Manie, the first serious tactical rendez-vous as riders jostle to be near the front. The climb’s a recent addition to the race, added to make life harder for the sprinters. It has a spectacular start with a large archway and a sharp corner. Go through this with the front runners and you have twenty seconds on the riders stuck mid-pack. From this point onwards the race is on to be near the front but never in the wind where ideally each pedal stroke is a calculated effort, just enough to be in the right place but not too much to waste watts.

A fast and technical descent off Le Manie brings the race back to the coast and the race speeds on to the feedzone in Ceriale where the speed is often high and a missed musette can spell trouble. The road now is often diverted away from the sea, hidden behind buildings like a service road that supplies the beach front shops and restaurants.

In time come three small capes, Mele, Cervo and Berta and by now the riders have 250km in the legs. These are small climbs but the distance tells and sometimes the wind is coming in off the sea which makes holding a wheel that bit harder. They’re each part of the race and the Berta is famous as the site of Coppi’s winning attack in 1949 where he rode off for his “appointment with the finish line.” Italy has many cycling memorials and there is one on the Capo Berta to commemorate Italian cycling’s holy trinity of Gino Bartali, Coppi and Girardengo. All past winners of Milan-Sanremo are engraved inthe stone too.

Then it’s on to the Cipressa. This starts with sharp right hander and quickly climbs above the coastal town of San Lorenzo, the nine percent gradient bites hard after 270km. This is a proper moment of climbing that can prove fatal for the sprinters. Television cameras often follow the back of the peloton to catalogue the dropped riders. After the race passes the coastal autostrada the gradient eases but the pace rarely does. Cipressa’s name is derived from “Cypress Tree” but “Oliva” would be better because olive trees line much of the road and the tarmac is stained black by fallen fruit. If it’s wet then the residual olive oil can be slippery. Talking of names the climb actually goes up to Costarainera, it’s only by a false flat that the races runs along a ridge to the village of Cipressa to start the toboggan-run descent.

The Via Avvocato Michele Fossa seems to be named after a lawyer. I don’t who he was, perhaps he made a living defending people who crashed on the way down? In 1984 Dutchman Jan Raas made a mistake and fell over a barrier. They found him hanging in an olive tree below. Every rider is now desperate to avoid losing positions and those who slipped back on the climb are trying to get back to the front. It pays to know every bend in the road. Off the descent and the back to the coast but for a while but only for a moment. Here the race can speed at 60km/h along the flat. There’s a glimpse of a lighthouse and then comes the final rise of the day, the decisive Poggio climb.

It’s real name is the Via Duca D’Aosta, an aristocratic name but for 364 days of the year the most unremarkable of roads. It’s a twist of tarmac that leads uphill to the village of Poggio and normally used by workers servicing the ramshackle glasshouses that flank the hillside rising up from the sea. Flowers are grown inside these hothouses to be shipped across Europe, perhaps some will end up on the podium as the race winner’s bouquet? The race guide says there’s a section at eight percent but that portion’s so short you need a good theodolite to find it. In fact the Poggio averages less than four percent and it’s a climb that’s so fast and intense you have to brake going uphill and lean crit-style whilst climbing. The descent is not steep but packed with a series of sharp bends, littered with polished metal inspection covers and bordered by deep drains. Imagine a downhill criterium to sprint out of every corner. The further you descend, the more the slope eases and finally the race hits the main road to Sanremo.

Unlike the other classics Sanremo is the kind of place that welcomes the world all year round. Italians know it for its flowers and a televised music festival. It’s an unusual place for a bike race. Roubaix is an economic blackspot, Liège is ringed by rusting steelworks and the Tour of Flanders finishes on a stretch of road so unremarkable it’s not worth describing. By contrast Sanremo is a gentrified place with palm trees, full of shops that sell ice cream or silk ties. A few left and right turns and the seaside finish line awaits.

Conclusion

Milan-Sanremo, you can say it in two seconds. Think more and you’ll probably define the race by the Cipressa, Poggio and finish line. But this is a special race where, because of the distance, every pedal stroke counts. From the start beneath Milan’s cathedral to crossing the Po Valley, climbing the Turchino and then the blue Med sea, this is a journey across Italy where in the space of seven hours you can sometimes change seasons.

Having looked the the route, a full preview of the 2013 Milan Sanremo race will be online for Friday.

Extra Photo Credits

Rice Fields by Flickr’s vagabondiamo

Capo Berta by Flickr’s camallo65

Alassio beach by Flickr’s Martina Rathgens

Sanremo by Flickr’s giokai421

Congrats!! For one more time, great piece!!

Keep up the good work!

Nicely done, thanks. We’ve created a guided tour itinerary for those who would like to follow this storied route. Here are details http://www.cycleitalia.com/la-primavera-milano-san-remo-cycling.htm on 2013, which sadly did not get enough interest to go this year, but we’ll try again in 2014. Note this tour is in MAY when we hope the weather is better than in March. The tunnel at the top of Passo Turchino is truly a special place, we really enjoyed working on the logistics of this route and are excited about bringing some clients with us in 2014. Vai Nibali!!

Great piece, thanks.

Great piece, thanks.

” Italy has many cycling memorials and there is one on the Capo Berto to commemorate Italian cycling’s holy trinity of Bartali Coppi and Girardengo.”

An e and a , and your piece is perfect. Thanks and Vai Inrng!

Ooops. The site was down and I lost a draft when I went over to tidy up a few mistakes from typing to fast.

As ever, happy for corrections and edits to be pointed out, they help the next reader out.

Sure thing. Your blog is superb, and helping ironing out small speeding errors is a nice way of involvement.

You didn’t get the a in yet? Still Capo Berto towards the end of that paragraph.

It is I…

What a lovely review combining history, culture, sporting relevance and tactics. I’ll have this with me when watching the race and as always it will add to my enjoyment. Cheers

Really enjoyed this inrng – but will this be the last time we see this particular course?

Good question. There’s talk of changes and I wondered if the move to Sunday might see the race go back to the old Via Roma finish.

The route’s changed over the years as they keep trying to make it harder for the sprinters but smoother roads, better bikes and improved nutrition mean the course is not as tiring as it once was.

Thanks INRNG: wonderful lead up to a Classic. If Taylor Phinney is providing inspiring reasons to follow pro cyclists, you’re providing inspiring reasons to follow pro races, regardless of who is riding. Chapeau.

Great read.

“The Via Avvocato Michele Fossa seems to be named after a lawyer. I don’t who he was, perhaps he made a living defending people who crashed on the way down? In 1984 Dutchman Jan Raas made a mistake and fell over a barrier. They found him hanging in an olive tree below.”

That’s like something from The Rider

Very good article!!! Will be there be one on the contenders???

Thanks. I’m doing a full preview on Friday with riders, weather and the other info specific to the race this year.

Thanks again for the great article!

I’ve just read about Costante Girardengo the other day. Won MSR 6 times! He was also from Novi Ligure.

Good article as per usual. But how about a ‘pronostic’ as the French call it?

Yes, this is just a look at the route and geography.

A full race preview with riders, weather, TV schedules and more will appear soon.

I’m flying over to San Remo for the weekend to watch the finish – can’t wait. I’ll be with my heavily pregnant wife so can’t decide whether we should try and watch the action from the Poggio (but away from shelter and restaurants, loos etc) or try and get a decent spot near the finishing straight. Any recommendations?

The Poggio has some cafés but not much. So with your wife Sanremo is the best bet. It’ll be crowded but you can find a big TV screen. Also once the race is over you can see all the riders milling around.

http://cycleitalia.blogspot.it/2010/03/miano-san-remo-wrap-up.html

There’s a nice place to eat atop the Poggio, “Il Rustichiello” where we enjoyed lunch and watched their TV until it was time to run out and see the race pass by. I wouldn’t trade seeing this for the finish unless perhaps I could score seats in the grandstands. Enjoy La Primavera!!!

BTW, great preview once again INRNG – superb stuff as usual.

And go Cav!

Good piece. The finish really should be at Via Roma again. Everything else can stay, Le Manie did enough to make the race interesting again.

Hoping for rain on Sunday (forecast looking good) and Nibali. I’ll probably tune in on Saturday though and wonder why there is no race going on. 😉

Great piece, thanks. I hesitate to ask since the blog is already so good, but other pieces like this on other classics courses which track the landscape and the towns that are passed through would make a fantastic addition. I understand that MSR is unique in that it is so long plus, unlike (say) LBL it’s not a loop, but it’s a great way to learn about the landscape and the country.

Feedback and suggestions are always welcome. I’m always interested in the location of a race, the local factors affect the sport whether it’s the terrain or the weather and more. So there will be more like this or related pieces explaining the area.

How fun to find out that olive trees can play a pivotal role in the race. Thanks for the great details.

You see these black and brown dots on the road but they’re not too slippery.

Since the olives were harvested back in the fall I doubt the roads will be too slick this time of year..the trees have been bare for quite awhile now. If they ran this race in the fall like Lombardia I’d be concerned about wet roads being extra slippery…but we ride around quite a bit in Liguria through olive groves and have yet to notice any real difference in grip….though not sure I’d want to risk it near the olive harvest time!

That was a good piece of writing! I could almost feel my pulse increasing as I got closer to the finish.

really well done!

Best review to date, outstanding! It made me feel like I was there, without the 12 hrs on the saddle. My heartbeat was actually rising as I kept reading, can’t wait for Sunday.

Great review.

Recommend title change. The title is a bit misleading. M-SR is the World’s longest “One Day Pro Road Race.”

Was just thinking the same thing, down under we have the Melbourne-Warrnambool, the second oldest race in the world after LBL that used to run for 299.1 km. I wonder what the longest is?

The title is explained by the “pro calendar” mention soon after in the text. The “Warnie” is shorter now, no?

Yep, ‘only’ 262km last year.

Thanks, man!

Felt like a homage to my favourite race!

Now gonna go to youtube to watch previous yr vids!

At least I will be racing saturday afternoon, which will keep me

a little preoccupied as I wait for sunday afternoon, especially since

they have moved the race a day further up the calender!

And again I’ll be a smart ass amongst my peers just because I read this. Priceless 🙂

Why do they have races so long? I can understand why some riders feel pressure to take drugs when you have to race this far so early in the season.

Why the long race? Tradition mainly, in that the races started 100 years were sold as huge tests of endurance to generate interest and bike manufacturers wanted to prove their machines were durable and could do 300km in a day.

Not sure about the doping, remember the 100m sprint in athletics is less than 10 seconds long and there’s not a single col on the route. But the list of people caught by doping is very long.

+1 And don’t forget there are guys who’ll dope to win a salami or “win” a Gran Fondo in New York.

Thanks, Inring you paint a picture worthy of being judged with the fresco’s in the Sistine Chapel.

Really enjoyed the article! Why do they call it “La Primavera?”

It means spring and the race often finishes in sunshine, the peloton enjoys warm weather. Not this year though, forecast looks like winter will steal the show.

great description , i’ll never think of it as along drag with a couple of hills and a sprint again!

this is why I love this blog