The Race Aganst The Stasi by Herbie Sykes

This is the tale of a cyclist called Dieter Wiedemann. His career as an international racing cyclist takes off at the same time as the Berlin Wall gos up. Wiedemann was on the wrong side.

The book starts with an introduction to the race, the politics and the history to give you a quick grounding it what will come. It’s hard to review the book without delving into the story but reading the book is all about the details so any plot spoilers here shouldn’t ruin it.

One thing I won’t spoil is the story of the British team riding the Peace Race. We get the usual impressions of the crowds but best of all, the anecdote that they were paraded in front of Konstantin Rokossovsky, commander of the Soviet forces in Poland, and decided to give him an original greeting.

Dieter Wiedemann makes the East German cycling team and rides the Peace Race, becoming a national hero and enjoying various perks and privileges. He is held up by the state as not just a champion but the embodiment of political success for ideology and propaganda.

“There was an elite class consuming things that ordinary people couldn’t buy in the shops. They had been chosen because they were politicians, sportsmen and suchlike.”

Sport gets used today. Any cyclist winning a big race gets held up as a wonderful example. Politicians pose for photos with Michał Kwiatkowski or Pauline Ferrand-Prévot. But the scale is quite different. Wiedemann becomes a national celebrity, his team mate Gustav-Adolf “Täve” Schur becomes a folk hero.

Even the race itself becomes instrumentalised, the Peace Race is a political project. Today the Tour de France is formidable promotional tool for France, exporting tourism and culture but the Peace Race was created to link East Germany (the GDR), Czechoslovakia and Poland, once enemies in war, years later satellite communist states in Moscow’s sphere. The book’s cover says “the greatest cycling race on earth” which is bold but Sykes puts the case. Its popularity is hard to explain but the video in this Polish TV documentary show huge crowds. How many really wanted to be there? Many were instructed stand outside in the name of politics and civic duty.

“For my parents, there was only the Peace Race. We never spoke about the Tour de France or other races.

Michał Kwiatkowski”

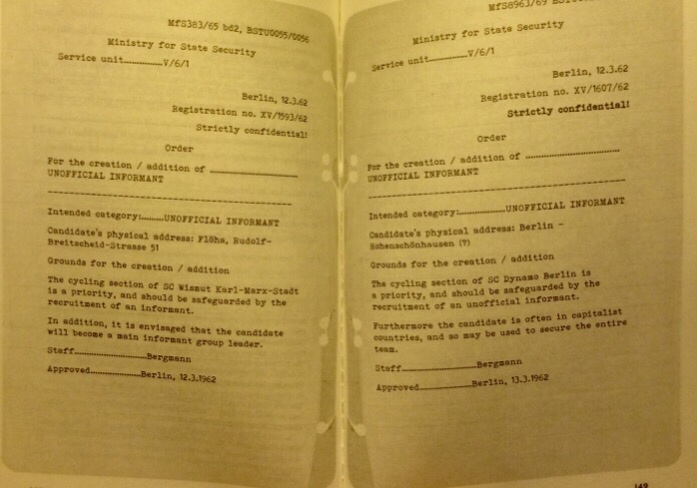

What’s not to like when politicians rush to embrace cycle sport and, even if there’s some compulsion, big crowds for a bike race sounds good. But it quickly turns sinister as the book calmly, coldly sets out the network of informants recruited by the Ministerium für Staatssicherheit, better known as the Stasi, the GDR’s secret police.

The book isn’t a straight narrative or biography, it’s a collation of interviews, letters, newspaper cuttings as well as archives from the Ministerium für Staatssicherheit, better known as the Stasi. Once top secret these have been made available following German reunification. They’re translated and included in the book an ersatz typed-up police report format. It’s chilling and tragic at the same time. Coaches, riders, mechanics all have code names as informants and are expected to swear secrecy to the secret police, reporting on whether their friends and even family are loyal to The Party.

“A week or so after the Peace Race I was out on my bike and a big EMW car came by me as I was climbing a hill. It braked suddenly and five blokes in leather coats jumped out. They told me they needed to talk with me and that they’d follow me home. I was very scared, as you can imagine, because I knew instantly they were Stasi.”

Presenting this variety of information means the book itself resembles a file, a collation of interviews, reports and press cuttings. Sykes has turned presumably long interviews into shorter components. This editorial work means the pages flow as you get a race report in a newspaper followed by comments from a participant, perhaps with a Stasi file note too.

When someone quit the GDR for West Germany the term “defection” was often used to encapsulate the political element, fleeing one regime for another. But Wiedemann primarily moved for love, to marry Sylvia. Only the Stasi and its prodigious network of informants cannot grasp this. In a world built out of politics all they can see is political reasons: frustration with the GDR team, material greed or conspiracy from agents in the West are cited as hypotheses for the defection and the actual version of him falling in love doesn’t compute. His parents are chillingly assessed. His father loses his job just because his son was a “traitor”. It’s said up to one third of the adult GDR population was an informant and these reports depict a bureaucracy sustaining itself with circular goose chases.

After defection he turned pro in West Germany with the Torpedo team, a brand of hubs belonging to Sachs (now a company owned by SRAM). Wiedemann rides the Tour de France with the German team in 1967. When Sykes is researching the book and mentions this to one of Wiedemann’s East German peers, he never knew because the Tour never reached that far east, not even that Wiedemann had ridden and finished. If the Tour didn’t have much meaning to East Germans, it doesn’t to this book either and only a few pages are needed to cover what happened. Wiedemann recalls a wavering Tom Simpson on the slopes of Mont Ventoux but such a major incident in cycling is but a footnote here.

If things had turned out differently?

If the Peace Race was a rival to the Tour de France it lacked one thing: mountains. Imagine a flatter stage race where Michał Kwiatkowski, Peter Sagan and Marcel Kittel compete for stages and the overall win. In a parallel universe where the Berlin Wall and Iron Curtain remain it’s possible to imagine a Pole, a (Czecho-)Slovak and an East German competing in a contemporary Peace Race. Kittel in particular is a product of the GDR Sportschule system’s legacy, dedicated sports schools designed to produce Olympic champions for the glory of country and The Party. The book suggests it could never have happened, the Stasi bureaucracy growing like a cancer, starving the rest of the country of freedom and consuming wealth that could have been invested elsewhere. Collapse seems inevitable.

The irony now is that it’s the West that does all the state-funded sports programmes. Kwiatkowski and Sagan turned pro with little funding nor programmes while cyclists in France, Britain or Australia are trained for Olympic glory.

Conclusion

This is a great book that mixes a variety of source materials to tell the story of a cyclist. Page after page you sense the tension rising as defection gets closer. When Wiedemann makes the switch it starts of a chain of new events rather than relief. The mix of sources, not to mention the translation work mean this has been a huge piece of work by Sykes, a story that deserves to be told.

It’s not for everyone : don’t expect a cycling biography, there is much on life as a cyclist in the GDR but it’s not the usual race reports. It’s a clever assembly of interviews and documents that creates drama and the factual content and mixture of source material make it as much a story for students of German history as cyclists. Is it even a sports book?

Some cycling fans won’t find enough sport because of its scope. If you like cycling and enjoyed the German film Das Leben der Anderen, The Lives of Others then this is a blend of the two. Worth turning a few pages in a bookshop or online via Amazon’s “Look Inside” feature to get a feel for it.

The Race Against The Stasi is published by Aurum Press and sells for £18.99 / $27.99.

Note: a copy of this book was sent free for review

More book reviews at inrng.com/books

@ inrng,

Nice review. However, I don’t understand the example of the Stasi reports in the book as pictured above. It is in English, not in German. Is it a translated copy?

Yes, they’re translated and included in the book an ersatz typed-up police report format, you get to read what the Stasi are thinking/doing while Wiedemann is racing or writing to his girlfriend. I’ll update it above to mention the translation.

Ah ok, now I understand;-)

You can see the original here:

I noticed this book on the amazon cycling book shelves some time back. Upon reading this review, I shall hesitate no longer in buying it!

And Kittel was born in 1988, so to say he is “a product of the GDR Sportschule system, dedicated sports schools designed to produce Olympic champions for the glory of country and The Party” seems a bit far off not? Ullrich, Heppner and Ludwig are better examples.

There’s missing word there, “legacy”. I think he went to the Erfurter Sportschule, today a college for those with sporting inclinations and the system he know. But once upon a time a factory/laboratory for the GDR’s sporting talents. Luckily for him and everyone else he’s racing free.

Everyone’s current favorite rider Jens Voigt is also a product of this system

Just one of many in all ways of life. Another in cycling is Wolfgang Lötzsch, so feared by his own country and the stasi that he was at one time locked away from cycling and life. Today he is in the german Hall of fame in sports. At least something, anything-although nothing can bring back the life he could have lived.

Lötzsch was Widemann cousin. His “defection” to the west was one of the reasons for Lötzsch’s misery (The other one his unwillingness to join the party), is that mentioned somewhere in the book? There is an interesting documentary about Lötzsch’s life: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1183157/ and a book I haven’t read (ISBN 3-936973-12-1)

Because of this Lötzsch could never ride the peace race, but still won quite a few very prestigious domestic races against they riders of the GDR riders, despite being on his own without the financial, technical and medical help of the system.

I have the book by P. Köster about Lötzsch, but have only read a part of it till now. One question which in this book turns up is of course the question what Wiedemann’s action meant for him. This is another dimension of such systems-in making decisions for your own life, you could decide it for others, too. A horrible responsiblity.

“If the Peace Race was a rival to the Tour de France it lacked one thing: mountains.” It is true, but it deserves a comment. It was a decision of the organizers (or of the communist goverments behind) not to include harder mountains. Maybe because the Carpathian stages could not beat the Alpine ones. Or because the Soviet riders would have complications in climb training. But potentially, quite hard mountain top finishes (true 1st category or even lower HC) could be found along the border of Czech Rep. and Slovakia to Poland, see e. g. here: http://www.challenge-big.eu/en/bigs/zone/10 or here in Polish: http://www.podjazdy.ovh.org/szosa.html and they are not (yet?) really included even in Tour of Poland. But now having Rafal Majka, we’ll see 🙂

Good point, it seems the stages were typically from one city to another so they could have the big crowds. I suppose today with the importance of TV these mountains could be explored.

I think the main issue here was the fact that it took place in Central Europe in the first week of May. Many, many Peace Race stages were run off in apocalyptic weather.

I remember following Peace Race as a kid many times. Once one of the stages or time trial had finish on top of very steep service road to ski jumping ramp in ski resort Harrachov and think Uwe Ampler smashed it, but weaker riders who were under geared were force to push their bikes on the foot.

Anyone interested in the role sport played in East Germany should track down the excellent documentary, Einzelkämpfer. While it does not focus on cycling, it does interview former DDR sporting superstars today and has some amazing file footage from the old days, highly recommended.

Trailer here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9HCXPPYYzNE

Any mention of DDR doping practices, they were known to go all out, with state support.

It’s mentioned in the book, yes. But it got more prolific after Wiedemann’s career was over.

To me it is hard to believe that doping is the thing that anybody even thinks about after reading the review. To me it is about a life, about history, about people and the sad things they do, the difficult or easy decisions life forces us to make. It is about telling stories, so they don’t get forgotten and because they need to be told. It is about telling stories so we may learn something about others and ourselves. And quite frankly, in Wiedemann’s or anybody else’s place I’d be hurt and find it disrespectful that instead of being interesting in his story and life, doping is the interesting subject.

+1

Thank you.