As the latest in the series to explore the famous roads of cycling, here is the Col du Tourmalet in the French Pyrenees. The idea is to discover the road and its place in the world, whether as part of cycling’s history or to look at the route on a day without racing and it is open to all.

The Col du Tourmalet is a legendary place for cycling, steeped in history and steep in slope. The first climb above 2,000 metres ever used for a race and with 75 appearances in the race, the most used climb of the Tour de France.

The Route

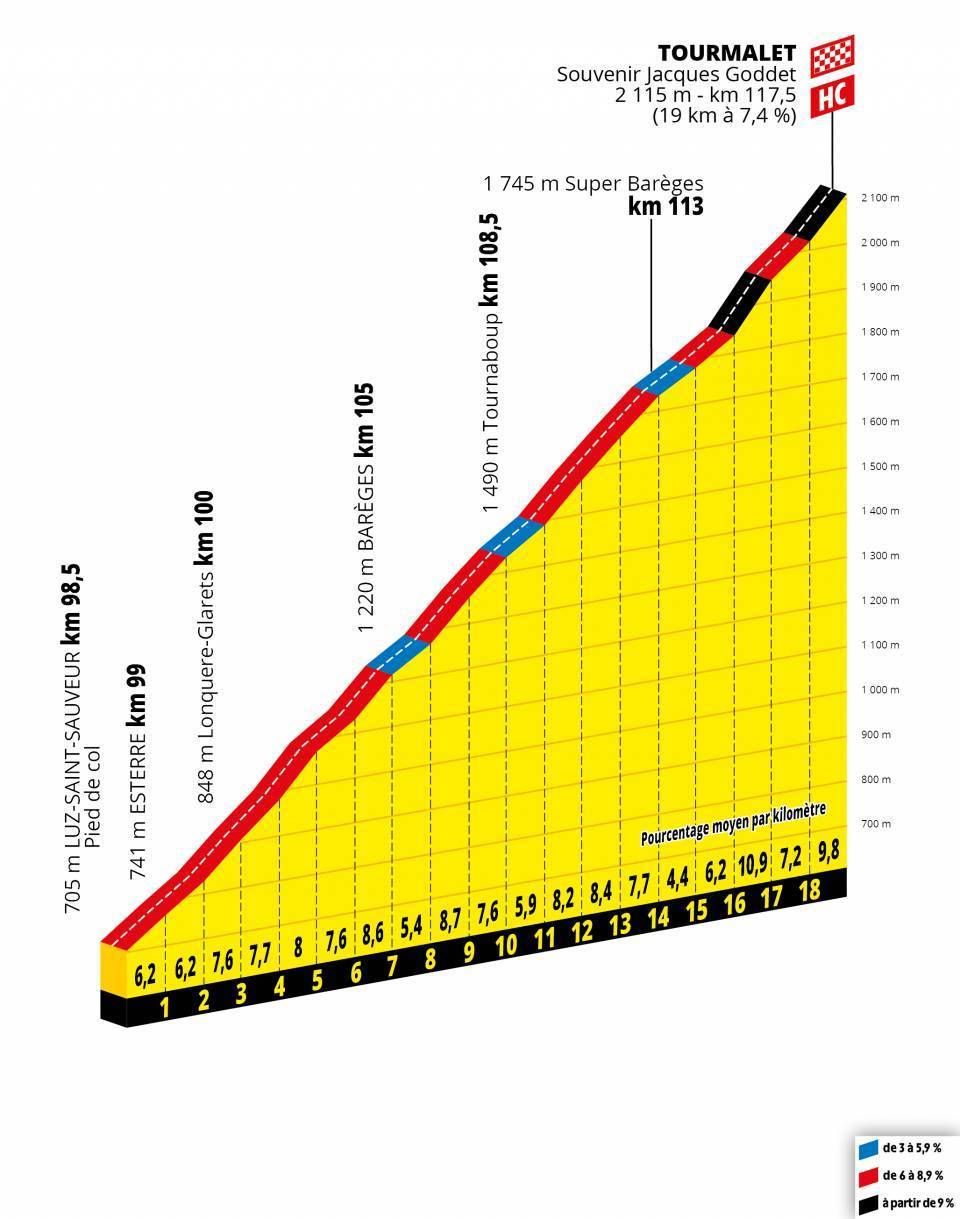

This piece will cover the west side. The D918 climbs out of Luz Saint Sauveur and it is 19.4km at an average gradient of 7.4% to the pass. Whilst many mountain climbs are famous for their hairpin bends, this climb is characterised by long ramps only interrupted by a few bends along the way.

The road climbs to the village of Barèges which has mutated into a ski station and after a short respite in the gradient the road rises again all the way to the top at 2115m.

The Feel

Unless you drive to Luz you will approach by the one road that leaves the town of Argelès-Gazost and rises up the valley of the Gave de Pau. This 18km road climbs via a series of tunnels, it is scenic in places but full of traffic and saps some energy.

Victor Hugo described the town of Luz as “lit by sunlight and lively.” The weather is not guaranteed but it is a busy place. It’s tempting to start fast, who wants to be seen struggling by the locals? But the slope will quickly tame any ambitions. The road is long and rather than winching your way up the face of a cliff like Alpe d’Huez here you are climbing up the Bastan valley. Helpful signs countdown the kilometres and advise on the gradient but they take their time and for those grinding up or on a bad day can pass slowly and bring nothing but bad news.

There’s traffic going up to the village of Barèges but the road is wide, two cars can pass without worry. In summer cyclists stream down in the opposite direction, the whir of freewheels and flapping jackets distracting from your regulated efforts. Barèges is ugly and lined with shops for tourists, seemingly dominated by a Polish family called Locationski whose bright signs are everywhere

The slope eases as you leave the town and when there’s a race on this is a common spot for attacks but just because the gradient feels easier doesn’t mean you’re going to soar for the last nine kilometres. After a large car park the gradient picks up and the slope gets harder and harder.

By now traffic is rare and the place has a wilder feel with rocks and little vegetation of consequence beyond grass but the road is wide. This is not the ribbon-like series of hairpin bends found on Luz Ardiden nor the woodland intimacy of the Soulor, it’s an open cathedral. This brings a relentless feel, you can always see where you are going. There is not a bend ahead to aim and you can often see what is coming for the next ten minutes.

Finally the end of the valley is reached and you can see the road picking its way up to the pass. Either this is a welcome sight or it prompts panic because the steep gradient is visible in profile. The last ramps are steep and the sombre rock leaves the impression of a hard place.

The Descent

If you’ve climbed up then it’s time to expend the accumulated potential energy. The wide road lends itself to a fast descent on both sides. This video clip shows the return to Luz.

Tour de France History

No other climb is so closely associated with the Tour de France. Alpe d’Huez might come close but as explained in this series it was only added in 1952.

The Col du Tourmalet was first used in the Tour de France in 1910. The story goes that the organisers of the Tour de France, the newspaper L’Auto, sent one of their men, Alphonse Steinès, to investigate whether the race could cross the Pyrenees. To cut a long story short, Steinès made his way up the Tourmalet but conditions were so bad that he ended up needing rescuing. Yet far from being wary, as soon as the hypothermia subsided Steinès fired off a telegram to Paris saying the road was “perfectly passable”.

Like many legends of the Tour de France Steinès’s reconnaissance trip has been told so many times over the years that the fog wasn’t just confined to the mountains. Exaggerations have made the tale ever more colourful, with accounts of blizzards, marauding bears and more. Regardless it’s a great example of how the early editions of the race were not so much sporting competitions but extreme tests of endurance and character.

In the 1920s it was not just a test of rider but motorcar and L’Equipe duly reported how varies following cars coped with the climb, the Peugeot “valiantly led” whilst the Buick “marvellously held strong.” The same paper reported the prizes offered by spectators, including “95 francs offered by a group of alcoholics in the Bar Gambetta of Rochefort.”

In 1947 a plane crashed into the slopes after Jean Robic led the race over the top. Carrying journalists it got too close to the race and the mountain where the wind caught the machine and it smashed into the road. Luckily the pilot and passengers were pulled out alive by spectators and had only minor injuries, whilst riders were able to pick there way around the wreckage.

Perhaps the most famous ride was in 1969. Eddy Merckx was already in the yellow jersey and in charge of the race. But on Stage 17 he took off on the Tourmalet’s final hairpin bend to leave an already select group. He pressed on solo during the descent, romped over the Aubisque and rode into Mourenx some eight minutes clear. In reality he was already leading the race so the others didn’t see fit to chase hard, they were going to come second anyway but nevertheless this was a crushing victory. It was so impressive that L’Equipe’s Pierre Chany instructed his colleagues to save on their superlatives, “economise, economise” he ordered. Perhaps it was the hot weather for as the day ended with a vivid sunset next day’s L’Equipe said the sky that evening “had something of the Olympic flame, as Merckx slept beneath that purple crib where living gods are born, ” the kind of prose you don’t read today. Merckx won the race outright, taking all three jersey competitions, the only time this has ever been done in the Tour.

In 2010 the 100th anniversary was celebrated with a summit finish, something that happened only once before in 1974 and the record ascension was set by Andy Schleck. It’s the col that has been used most often by the Tour. It’s early inclusion in the race helps the count but the main argument is the Tourmalet’s central location in the Pyrenees, it is easy to include and can be combined with other cols and a variety of start and finish towns.

Pic du Midi

Cyclists known mountain passes as the high point of a race but they are often the lowest point to cross a ridge or mountain in order to reach the other side. However the mountain pass is marked by the Etape Café and a large statue of a cyclist as well as a memorial to Jacques Goddet, the former Tour de France directeur.

But from here it is possible to onwards and upwards to the Pic du Midi observatory. It means “peak of the south”, or literally “peak of midday” at sits at 2877m but the road is not well surfaced and only for the intrepid with sturdy tyres.

Say It

There’s a small dispute over the meaning of the name. Tour and mal imply a journey and something bad but these words are modern French and the older gascon language of the past did not use such things. Regardless, the “bad detour” label has stuck. For many in France Tourmalet rhymes with Tour de France, it is so closely associated.

Travel and Access

The Pyrenees are a remote part of France and far from Paris and its international airport. Toulouse is the region’s main city but still hours away in the car and further by rail. It pays to visit the region for a few days as you can explore many of the famous climbs and also some of the lesser known routes which can be more rewarding for their scenery.

Argelès-Gazost is a fine place to stay, there are other small towns. Of the larger cities, avoid Tarbes in preference for Pau.

Main photo with persmission of Flickr’s shht

More roads to ride at inrng.com/roads

“seemingly dominated by a Polish family called Locationski ”

Love it!

Tom

+1

Rode up the other side from Lourdes just before the Tour last year! Amazing place! Didnt fancy the pass and descent as climbing back fulled on the previous nights red wine could of proved all too much!

Lourdes are nearer the west part (something a little over 10Kms to the north of Argeles-Gazost. Are you sure you did the eastern slope? (the main town from this side is Bagneres-de-Bigorre)

Agree, this is definitely the superior side of Tourmalet – “open cathedral” is a great description.

Recently on this side they have blocked off a 3.5 km detour stretch above Barèges to bikes only and labeled it the “Voie Laurent Fignon” (cars take a more direct route). Photo of Fignon sign here: http://www.flickr.com/photos/willj/7951638704/

It’s worth taking this quieter option. I think the Fignon cycling center is at the bottom of the other side of Tourmalet?

The link you posted to Pic du Midi was the just about the most fun I have ever had on a bike. The route is stunningly beautiful – gravel surface and closed to cars since quite a few years ago. The surface gets worse nearing the top. Even the strongest cyclist will have to carry the mountain bike on the last stretch up a walking trail after the road ends at the old auberge. But it’s magical at the observatory. Highly recommended.

The Voie Laurent Fignon is the original D918 route over the Tourmalet – the ‘new’ route through Super Barèges was originally just an access track to the chair lift station there. It is nice to take the quieter route, but my only complaint with it is due to the lack of cars, the surface doesn’t get ‘swept’ so there’s a lot stones and small rocks (I definitely wouldn’t descend down down that way!).

The ‘Cetntre Laurent Fignon’ was in Bagnères de Bigorre but sadly has now closed down.

The Voie Laurent Fignon is one way, you’re not allowed to descend on it.

The new road on the other side of the valley gets more sun in spring and has less risk of avalanche, it can be opened 2 weeks earlier than the old road.

The Fignon centre was never profitable, it was subsidized by Le conseil général des Hautes-Pyrénées. When Fignon died his son wanted to continue running it but the conseil général pulled the plug.

“It’s tempting to start fast, who wants to be seen struggling by the locals? But the slope will quickly tame any ambitions.” So very true, all decked out in your top kit on display to the locals it begs you to give a little gas early on, but you will suffer quickly – no worries though, you still have plenty of km left to regret the mistake.

I saw grown men crying on the tourmalet attempting to get to the top at the end of the 2010 Etape du Tour.

Oh yes, that 35 degree heat was one to remember. And I agree about the good feeling in Luz, but how quickly the pain sets in! My recollection is that actually it is steep after Bareges for a short distance – around 10%, and then it levels a bit after the giant car park and also you can get some shade under a cliff at that point.

A giant and a pleasure to ride. I like the version from St. Marie de Campan too. It feels more intimate and it usually comes after having passed the Aspin or the Hourquette D’Anzizan. In my experience it is always cold in the last few kilometers of the Tourmalet (once you pass La Mongie ski station) so have yourself for a wonderful onion soup at the restaurant at the top and then put your wind gear and long gloves for the descent all the way back to the town of Bagneres de Bigorre.

According to one of my neighbors who is a native Gascon speaker, a direct translation into English would be “distance mountain” or “long mountain”. The “bad detour” is simply wrong.

“Finally the end of the valley is reached and you can see the road picking its way up to the pass. Either this is a welcome sight or it prompts panic because the steep gradient is visible in profile. ”

One my first time up, it prompted a full blown panic attack 🙂

It should also be said that the shop at the top sells a nice range of commerative jerseys at reasonable prices. I made my wife drive up with me the next day so that I could buy one. I felt the need to tell the shopkeeper that I had cycled up the previous day and had thus earned the right to wear it.

Notice the unmistakeable vertical slats and round headlight of the American Willys Jeep in the background of the plane crash picture. Being a cycling fan and a vintage Jeep nut, this has got to be one of my favorite pictures of all time!

Great read, great pic.

This has probably already been said, but you should collect these articles in a book. At least an e-book 🙂

Interesting, I might sweep them all up and use a link at the top of the page, similar to the collective page for book reviews, eg http://inrng.com/books/

“dominated by a Polish family….”

!!

it took me a while

that’s smart!

🙂

I’m a 58 year old female cycle tourist and I plan to climb the Col du T this summer on the grounds that if I don’t do it now I never will. I’m going to spend a night at Bareges on the ascent and I’m happy to push my bike up to the top if that’s what it takes to get there, but I’m still a bit scared by its reputation, and the fact that all the photos show young fit men in Lycra. Are there any other middle aged women out there who’ve done it?

All ages go up. It’s tough work but if you can ride hard for two hours you’ll make it, just be sure you have the low gearing to suit. Also take some warm clothes for going back down.