The mountains have long remained a mysterious place where the truth can be as murky as the fog. Before the railways made France accessible, many believed those who lived in the mountains were freakish figures and imagined strange beasts roamed wild. It’s not all false, today you will find bears in the Pyrenees and wolves in the Alps.

Cycling loves its myths and each July sees the race return to the Pyrenees. Like a child visiting a grandfather, the same stories are told every year. There are the broken forks of Eugène Chistophe, the cry of “assassin” from a Octvave Lapize as he passed the organiser on a steep climb and more. Only many of these tales are exaggerations and even fabrications.

It’s often said the Pyrenees were the first mountains of the Tour de France. False. The Tour climbed the Col de Pin Bouchain and the Col de la République in 1903. Then it visited the Vosges, tackling some long passes in 1905 including the Ballon d’Alsace. The Pyrenees didn’t appear until 1910.

In 1910 the Tour organisers sent a reporter called Alphonse Steinès to review the Pyrenees. To cut a long story short he made his way up the Col du Tourmalet to determine whether a race could be held on the roads. But conditions were so bad that he ended up needing rescuing. Yet far from being wary, soon as the hypothermia subsided, he fired a telegram to Paris saying the road was “perfectly passable”. Like many legends of the Tour de France Steinès’s reconnaissance trip has been told so many times over the years that the fog wasn’t just confined to the mountains. Exaggerations have made the tale ever more colourful, with accounts of blizzards, marauding bears and more.

Forked Tongues

The story goes that Eugène Christophe broke his forks on the descent of the Tourmalet and then made his way downhill to a blacksmith in the village of St Marie de Campan where he repaired the forks. Riders had no mechanical support and the rules stipulated they could not receive outside assistance. Only in the forge the blacksmith’s boy was operating the bellows and a zealous official penalised Christophe and he lost the race.

However, the reality is different. Christophe was docked three minutes for this extra help, a blink of an eyelid in the days when the margin of victory in the Tour was huge; he lost the Tour for other reasons. Instead Christophe was sponsored by a bike manufacturer and having broken his forks, tried to find a small path to descend the Tourmalet where he could hide the mechanical failure from the press pack, in case news of his unreliable bike leaked out. This sneaky detour, to protect a commercial interest, cost him far more than the three minute penalty.

Assassins!

In 1910 the race first visited the Pyrenees and the Aubisque was the first col. It was so hard only three riders managed to ride to the top, the others were forced to push their bikes up on foot. No wonder given the rudimentary bikes without gearing and the gravelly path. But the first rider to the stop was Octave Lapize who reportedly shouted “vous êtes des assassins“, “you are assassins” to race promoter Henri Desgrange at the top of the climb. False.

Desgrange was back in Paris, overseeing the chronicle of the race via the publication of L’Auto newspaper. Instead when Lapize reached the top, he saw Victor Breyer who had the dual role of race reporter and race official. Lapize was unhappy and Breyer asked “well Lapize, what is it” to which Lapize replied “You are like criminels. Tell Desgrange from me that you don’t ask men to make an effort like this. I’m fed up.” Criminals, yes but the tale of “assassins” seems to be an exaggeration added in time.

Conclusion

Stunning countryside, savage slopes and some amazing racing make the Pyrenees a special place. From the early days of the sport a century ago when Christophe said “this is not sport, this is not a race, it is the work of a brute” to post-war tales like Wim Van Est’s fall and Eddy Merckx’s rise on the roads from Pau to Mourenx, these mountains have given the sport plenty to talk about.

But like many accounts from the past, they can be prone to exaggeration, especially given the organisers and media had an interest in promoting the race and a bit of hype was good for business. These tales reappear every year, they’re comforting if you like repeats… but not always accurate.

Good read. There can’t be many other sports with such a rich history.

Mark, London

I dunno, I think most major sports have their mythologies. Part of what really makes cycling at least feel that it has a lot more depth is that the countryside is the playing field, so the actual landscape is part of the legend, as opposed to most other sports, which take place on or in artificially constructed environments of one sort or another (mountaineering excepted, I suppose).

Exactly, being able to borrow the landscapes makes such a difference plus the sport lends itself to drama with crashes and outside factors like the weather.

“Only in the forge the blacksmith’s boy was operating the bellows and a zealous official penalised Christophe and he lost the race.”

Just heard them repeating that old chestnut on the ITV commentary.

Maybe they should read your excellent blog before going on air.

I knew the story would get an outing today, it always does since the race almost always goes through St Marie de Campan.

Thanks for that. I don’t think I’ve read that version of the Christophe anywhere, even in Sweat of the Gods. Where did you get this version (and the Lapize story) from?

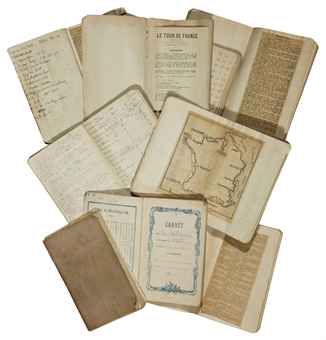

A few sources, including Sweat of Gods. But also “Cols Mythiques du Tour de France” by L’Equipe, my mountain bible.

Ah, monsieur has the advantage of me! I shall have to learn French.

Perhaps the biggest myth of all is that racers in the Tour de France were the first cyclists who rode over these mountains.

In fact, ordinary cyclotourists had been riding ‘the circle of death’ for years. Here’s an entertaining account from 1879 of a group of members of the London Bicycle Club who rode (or more likely, pushed) their high wheelers over the Aubisque, Tourmalet, Aspin etc.

Graeme Robb’s excellent book The Discovery of France tells of a teacher from Chartres on a cycle touring holiday crossing the Tourmalet in 1895 and hundreds of men and women doing the same before the Tour first went there in 1910.

It is interesting to know the truth behind these myths..

..but I choose to put them aside in favour of the ’embellishments’ that time and enthusiasm have layered over the Pyrenees..!

You’ll be taking the Tooth Fairy away from me next..

Yeah, I’m happier with the colourful versions of these tales.

It reminds me of a documentary about cricket umpire, Dickie Bird. In it, he tells this story where play is halted because of light reflecting off a glass door or something. In his version, he made all these great witticisms when trying to get the situation sorted. The documentary then cuts to some footage of Dickie yelling: “Shut the door! Oi! Shut the bloody door!”

I’ve just realised that I’ve probably embellished a bit when telling you that.

They can have the Tooth Fairy, just don’t touch my Norse Gods.

“Mountains of Myth” make for typical examples of story-telling that stand the test of time, even if they are exaggerations. Your ongoing accomplishments of presenting these stories with great local detail are much appreciated 🙂

The desire of the mind to embellish upon “facts” often make the actual facts fall by the wayside, but we fans soak it up and carry the story through the decades; each “edition” that’s told is a bit more removed from the last, making the story legendary in the press and in the minds of followers.

Contrasting with what we have today, Stage 16 and the infamous Tourmalet, I must say that the “fireworks” I hoped for were only in one man’s legs — Thomas Voeckler. The man never says die, and though he’s not the fav in the peloton, he has no fear or lack of heroics up his sleeve, launching attacks which stick and winning stages with huge gaps! Chapeau Voeckler!

This Tour has felt like the “SKY Tour,” which has been carefully calculated and “trained for” and that’s impressive, but the attempted attacks by Wiggins’ challengers have all fallen short, diminishing the excitement factor. But, in the spirit of legend, this Tour will likely be talked about decades from now as an epic edition. Unless Nibali pulls off a miracle tomorrow, Wiggins has this one in the bag.

It ain’t over until it’s over. We saw today the Pyrenees can crack even a top-flight rider like Cadel Evans, and cost him 5 minutes. Odds favor Wiggins, but a bad day would make for an interesting time trial on Saturday.

so where was the united effort to attack Sky that VdB was going on about? Nibali goes off and no one steps up and follows? Nibali and Vdb (with a little help from LiquiGas and Lotto) had the chance to do some real damage …

one more chance tomorrow … and i think TeeJay will climb one more step up after the ITT?

Great stuff. For those interested in the history of the Tour in the Pyrenees, there’s an excellent French-language work on the first high-mountain étape of 1910, called “L’étape assassine” by Jean-Paul Rey. It’s written as a historical novel, mixing well-researched fact with some imagination to add depth and character to the events. A very recommended read for all francophones, that was published as a limited edition to celebrate the centenary in 2010. I picked one up from amazon.fr.

Nice piece. Still, the story of the broken and re-welded fork, and the albeit small penality he suffered from it, says tons about a certai spirit of the race, consisting of putting men to confront endless adversities with the only help of their own forces. It’s the same spirit of Paris-Roubaix in the wind, Tour of Flanders in the rain, a mountain stage on the Dolomites in the snow, a marathon to Avila at 40º, or a 90km TT. After all these years, I still haven’t heard a single valid reason why riders shouldn’t fix their own punctures, having to travel with spares as in the old days: changing a tubular is cycling too.

The word “sissies” comes to mind at this point, but the last time I used this word here I got told off for “gender” issues. I wish I knew another word to convey the same sense of spite.

I’d say it’s just the inevitability of change. Times change, and so do the way we do things, pretty much all things.

I wouldn’t call modern pro cyclists wimps. I’m sure Octave Lapize would be soundly beaten in the modern tour as he obviously wouldn’t have the levels of aerobic fitness of the modern rider. Similarly, Contador would have been soundly beaten in an early tour as he stood at the side if the road forlornly trying to mend a puncture and work out how to change gear.

Different times, different conventions, different strengths required from riders. Why suggest any one skill set is superior to any other?

The book I mentioned above covered the topic of chcling conservatism quite nicely with a (fictitious) diatribe from Desgrange raging about how gears on bikes were turning cyclists into wimps. Even in 1910 there were people who thought the cyclists were wimps (I’m presuming that Rey based his imaginings on a certain amount of fact).

Boonen breaking away from the field and capturing his 4th Paris-Roubaix was pedestrian?

Andy Schleck rampaging away from everyone else on the Galibier last year was average?

Contador destroying the entire field in the Giro, Tour and Vuelta was cycle-tourist fare?

are you watching Bass Masters by mistake?

by that logic, almost anything we do, by comparison to a more poetic (and quite fictional) by-gone ‘romantic’ era would categorize us as wimps … why use locking pedals? more than 3 gears? less than 40 spokes? why did we ever give up handlebar mustaches, dirigibles and penny farthings?

does anyone have any more facts for our geography homework *yawn*