This weekend’s Paris-Roubaix has to be the unique race on the calendar. Its cobbles are enough to make the Oude Kwaremont look new. The velodrome finish is unusual but the exceptions don’t end there, this is a race where reaching the showers has become part of the ritual. Even the name stands out, Roubaix is celebrated as a strong brand by the cycle-trade when in the reality it’s France’s poorest town and rarely something to celebrate.

This is a reworked update from a few years back before the race preview gets done this lunchtime.

The race didn’t start out this way. Like many if not most races, it was launched as a money-making publicity stunt. At the end of the 19th century Roubaix was France’s textile capital, the “Manchester of France” to cite Britain’s bastion of the industrial revolution. Two wealthy cloth entrepreneurs put up money to fund a velodrome in Roubaix. Keen to attract crowds to the track, they hit upon the idea of a race from Paris that finished on the track, the culmination of such a long ride would occur right in front of an attendant crowd of workers who’d paid money to watch the finish.

So far so normal, it wasn’t until after the First World War that things started to change. In an account by the late Jean-Paul Brouchon, passing through the region rider Eugène Christophe proclaimed “here is the real hell of the north”. In this race won by Henri Péllisier, 40 following vehicles started but only five made it to Roubaix. We should use the term “hell” carefully, hell is the legacy of war rather than a bouncy farm track. The race wasn’t alone in riding through the area, Rouleur tells the tale of the Circuit des Champs de Bataille from 1919.

Post-war reconstruction came twice and by the 1960s Paris-Roubaix was a race that reflected modernity as cobbled roads all over Northern France were being sealed with tarmac. With growing income and improved technology it was possible to watch the race live on TV and French television deployed Robert Chapatte, apparently the first in TV sports commentary to work alongside a co-commentator. But as exciting as the novelty might be, live television only exposed the dull landscapes and the often processional aspect of bicycle racing. In the past cycling had been a fine sport to read about, the mere act of riding from Paris to Roubaix was a feat to marvel at. Suddenly TV required action. The organisers responded and in 1968 the start was moved to Compiègne, beginning a conceit that exists to this day: the race starts nowhere near the French capital. While the main roads had been resurfaced many tracks created to haul mining equipment from site to site remained.

The son of Polish immigrants Jean Stablinksi worked below ground as a child and spent his spare time playing the accordion at weddings and parties to earn enough money from which he bought a racing bike and eventually turned pro, winning the world championships in 1962. It was “Stab” and Edouard Delberghe who showed the race organisers the Arenberg Forest section as they hunted for new roads to make the race more exciting. As France modernised, the race regressed to a battle across old roads and it’s this switch that’s given the course its identity. Today the route is preserved and celebrated as part of local heritage but are hidden to most who cross the region by car or train where the brick houses, electricity pylons and mining slag heaps are the only things that break the linear horizon.

The difficulty of the cobbles makes the race a shop window for the cycle trade where the most extreme race of the year is used to sell goods for everyday use. If a bike can stand up to the cobbles then it’s strong enough to be used by weekend warriors. Carbon rims looked fragile until they passed the pavé test. It’s an old idea, the earliest bike races were marketing ploys to suggest if a bike could last a long race then it was good enough to ride to the farm or factory. Today no other race offers the same validation.

Arriving in Roubaix might be the stuff of pro cycling dreams and marketing messages but the reality is somewhat different, Roubaix has an unflattering range of socio-economic statistics and tops the list of France’s poorest towns and cities with 45% of Roubaix’s population living below the French poverty line. The other day when President-candidate Emmanuel Macron wanted to launch his second-round election campaign he came here and for a reason, it’s a bastion of support for his rival Marine Le Pen, more precisely he visited Denain where the women’s race starts. There’s an unemployment rate well above the national average and some of France’s highest obesity rates. The textile industry that indirectly created the race vanished long ago and the town had a sideline in mail order catalogues which have predictably been picked off by the internet. Many cyclists might long to arrive in Roubaix but many locals might dream of an opposite journey, leaving Roubaix to make it in Paris. Still, things are on the up, Roubaix’s got new museums and the wider Lille area has been capitalising on its location a hub in the wider Eurométropole region between France and Belgium thanks to its transport links.

If cyclists long to arrive in Roubaix it’s because they’ve conquered the cobbles in a race that hurts like no other. The appeal is helped by the Roubaix velodrome which offers a victory lap for all who arrive and the strange showers inside. The original velodrome that inspired the race has been demolished and the current finish line’s future isn’t certain to remain as the new Stablinski velodrome with its indoor track and “Le Stab” makes the old track redundant. The showers are a curiosity, Paris-Roubaix is the only race where the post-race facilities are part of the legend, helped by the need to wash all that mud away when in other races a wipe with a damp cloth is enough. This is more than a washroom, it both a museum and Elysium, a resting place for heroes.

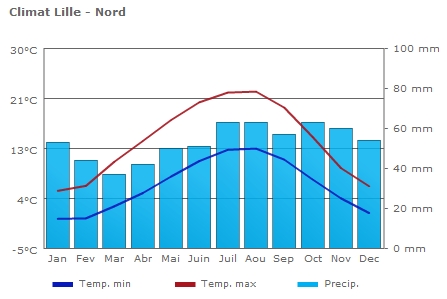

The showers are plumbed because rain showers are a rarity, curiously the race takes place at the height of the region’s dry season. It hasn’t rained since 2002 despite the surrounding Lille agglomeration being France’s 13th out of 118 for annual rainfall. The chart above is from climatedata.eu and the vertical bars are precipitation. The driest time of the year? March and April while July is the wettest which explains why it’s more likely to rain when the Tour de France visits in the summer.

The Tour de France’s use of these roads is also a big celebration of Paris-Roubaix. Too often Le Tour obscures the rest of the sport, it is the reference point by which so many other races are judged. Yet it “borrows” the roads of Paris-Roubaix. We don’t talk about the Tour “borrowing” the roads of the Critérium du Dauphiné or the Route du Sud, in fact the Tour is so big it has made makes Alpe d’Huez, Mont Ventoux and the Col du Tourmalet famous. This July though the Tour de France will be on another race’s turf, Roubaix’s legend heightens the the Tour.

Summary

There’s no other race like it. The cobbles are special with rougher, larger stones than are typically found in a Flemish race, some competitors will arrive in Roubaix with lacerated hands and this is used to demonstrate the toughness of bicycles. It’s a race that’s unique for other reasons too, arguably one of the first bike races to bend to the TV era and seek out spectacle and today the last major race to finish on a velodrome. The sport visits for a weekend but for the rest of the year Roubaix can be a bleak place.

Brilliant article as always.

I have always found thing race a bit of a curiosity (especially as it is now normally dry) but this background defines its readon for being. Probably won’t ever be my favourite but at least now I understand it.

For a race that owes so much to modernity and television, it does provide a real link to the sport’s working class roots too.

And in an age when racing bicycles are ever more expensive to purchase and almost the domain of the more wealthy and, when so many races seek out the glamour and tourist honey pots as destinations, I feel that this race is needed more than ever.

I’m also glad that Inr Rng has pointed out the real reason for the use of the term’Hell of the North’.

Far too many cycling articles use it with reference to the rough terrain.

The sight, as I looked into the far distance following the rough unmade “track” across the green fields, hearing the helicopters approaching, the lead motorbikes manhandling past and then spotting the first riders was an experience I will never ever forget.

The most Roubaix moment that always comes to mind is when George Hincapie suddenly sat up, with his handlebars flapping round his front axle. Bang, the bike had said, ‘Thanks, but no more’.

The classic Kelly photo (1984?) at the top of the article shows the cobbles as worse than they probably are now – and the race thus slightly less dependent on good fortune. Most of the worst sections have been relayed since Kelly rode then, and since I completed P-R as a cyclotourist in 88. I well recall that the crown was the place to be, but that getting back up there from the sunken ruts over wet cobbles required nerves of steel. I still have the stamped record card as a proud suvenir.

I presume that you were riding on a steel or aluminium frame DJW?

I don’t think I’d fancy that 😀

Still less using my own bike either, definitely hire one.

Hi Ecky, Ellis-Briggs Reynolds 531DB Campag Record/Cinelli (just like Eddy!) top to bottom – and I was stupid enough to give it away a few years ago! Lighting was Ever-Ready providing a feeble and unreliable (a thump required from time to time) light. Surely modern lighting is a bigger improvement than almost any other aspect of cycling. Ever-Ready: maybe they were joking.

Haha, Ever Ready, another of the engineering demonic hierarchy, along with Joe Lucas, Prince of Darkness

As you say the conditions have improved, but only just, the pavé are rideable in some sections but monstrous in others, you just don’t want to ride race bike down there at speed because you fear you’d trash the wheels and possibly the frame and forks as well. Nicer to have them free from the team.

We should note the Tour has sometimes used the Paris-Roubaix pavé but often the gentler ones, relying on the association and hype to terrify riders and thrill spectators. This summer they really do use some of the hardest sections.

Worth riding the route or the cyclo event but it’s like the saying the Japanese have about climbing Mount Fuji, “it is wise to do it once, foolish to do it twice”.

This is becoming my favourite mistake made in Slavic names:

Stablinski -> Stablinksi

Slafkovský -> Slafkovksy (https://sportnet.sme.sk/spravy/hokej-juraj-slafkovsky-menovka-slovensko-finsko-zoh-peking-2022/)

Anyway, very good reading, as usual, thank you.

Note Stablinski came from Stablewski. Jean’s father is named as Martin Stablewski, presumably Marcin since we’re on name changes. He moved from Poland to France in the 1920s.

Care to expand on this? I find this sort of stuff fascinating 🙂

I like your statement on the mid/late 1960s: “as France modernised, the race regressed to a battle across old roads”. That period when the race shifted from industrial cobbled roads to primitive farm tracks really is intriguing in the development of the race’s identity. I find it curious that, for so many of us, the image of Paris-Roubaix as an ancient, primitive spectacle is defined by ‘A Sunday in Hell’, and yet that 1976 film is really depicting an event whose specific character had only been established a decade before. Perhaps like giving the gravel roads of Paris-Tours a similar treatment today (maybe that’s a bit of a stretch).

The early editions were still defined by a lot of cobbles but this was the paving method of the time, and to this day many streets in Paris and northern France are cobbled for charm and heritage and Paris-Roubaix was long known for its cobbles. Some sections were hard because the roads weren’t in a great state but yes, it’s with Stablinski sharing the Arenberg section and more that the race really took on the character we know today. The race may be well over a century old but the race’s identity is really shaped by the second half of this as it remained old and tough while so many other races changed. It’s not alone, the Ronde of course seeks out cobbles rather than touring Flanders and climbs like the Paterberg and the Koppenberg are “new”, coming in 1986 and 1975.

You’re right, of course. I listened to an interview with Barry Hoban once, where he made the point that the northern classics didn’t really have cobbled sections, whole races were cobbled. Quite a thought. Although it appears from old clips of Coppi etc, that riders understandably sought the refuge of the pavements as much as possible.

As already said, it’s probably the only race that follows the old motorsport adage of “Win on Sunday, sell on Monday”. That’s why most of my bicycle purchases have been of this type of bicycle. The tech is far more relevant to me than some lightweight climbing or aero race bike…..If you ride on rough, pot holed, gravel strewn roads, then every ride is like you’re riding P-R.

Interesting idea – that consumers buy this stuff based on P-R. IMHO it’s more gimmicks than anything when you think that Duclos-Lassalle’s Rockshox gizmo was supposedly locked-out the entire race while Sagan had to borrow a wrench to fiddle with the suspension stem gimmick on his Big-S bike that year while yesterday’s women’s victor used a bike with a single front chainring (because SRAM’s front changer works so poorly?) and without Big-T’s marketing gimmick in the front and a non-adjustable version in back. Meanwhile, the tire pressure gizmo that DSM was supposed to debut seemed to be a non-starter? Add in the past disasters of Hincapie and Museeuw and Paris-Roubaix might be known as a marketing-maven-driven gimmick showcase as much as anything?

The Rouleur article about the Circuit des Champs de Bataille has gone now but there’s a shortened version of the article here: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/bike-blog/2014/apr/08/circuit-champs-bataille-tale-toughest-cycle-race-ever

Tom Isitt wrote a full length book on the subject too. I’ve read it. It’s interesting.

Watching the clip of Stablinski being interviewed, it struck me that his escape from the mines via bike-riding was a really deep-rooted background in the history of the sport. So many of the early riders escaped an equally hard or even harder life by racing. So Stab in the early 60s was tapping into a tradition that still just about existed amongst his peers.

Have there been any comparable stories since the early 60s, in our ‘modern, post-industrial’ society?

Surely lots.

Despite a general economic boom across Europe in the 1960s, there were still many towns and cities that were one-track ponies to the heavy industries that remained until the early 80s.

In Britain, think ship building around Glasgow and Belfast and steel and coal in the north of England and south Wales.

Although, oddly, the strict amateur stance of the dominant sport of Rugby Union in Wales forced its players to remain in their jobs as unpaid sportsmen. The tale of Llanelli beating the All Blacks is memorable, most were employed in the local industry of the area and returned to work on the next shift despite making history.

Nice to read this again for a refresh before the race. For the next update you may consider changing the last sentence to note the race now visits for two days given the Femmes race on Saturday has turned it into more of a weekend carnival.

Thanks for the updated version of this post, appreciated reading it. The Jean-Paul Brouchon Look was fascinating, and beautifully captures the profound contrast between the original “enfer du nord” and the celebration of cycling that Paris-Roubaix now is.

Sadly, the Rouleur link didn’t work for me – went to a 404 on their site. Does it need a subscription to work? For those with the same issue as me, the Wikipedia article, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Circuit_des_Champs_de_Bataille , And a longer article (which really captures the feel of this remarkable race) is at https://www.westernfrontassociation.com/world-war-i-articles/riding-through-the-ruins-of-war-on-the-circuit-des-champs-de-bataille/