A quick look at the route ahead while the headline is that this race should see the the first clash between Tadej Pogačar and Jonas Vingegaard.

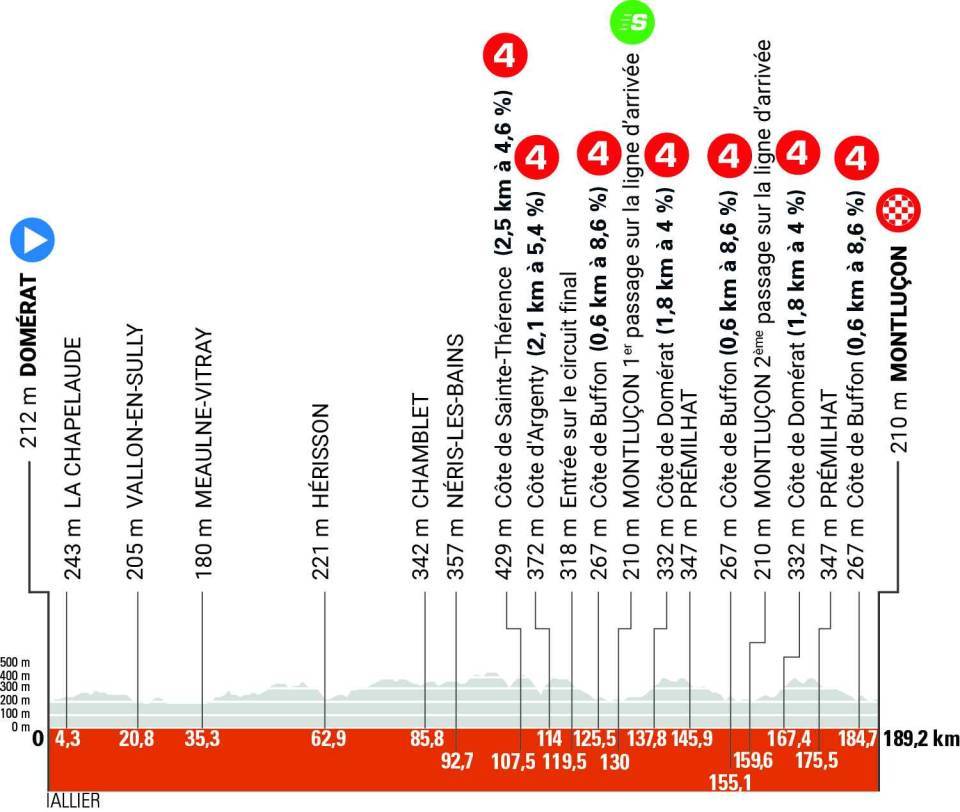

Stage 1

In 2022 Paris-Nice had a time trial stage between Domérat and Montluçon, the same again but with a long loop into the countryside and then finishing laps in Montluçon, birthplace of Roger Walkowiak and where Julian Alaphilippe. The Montluçon circuit is harder than the profile suggests, Domérat is a long climb with some awkward sections, Buffon is in town with an irregular road that pitches up with 12% sections.

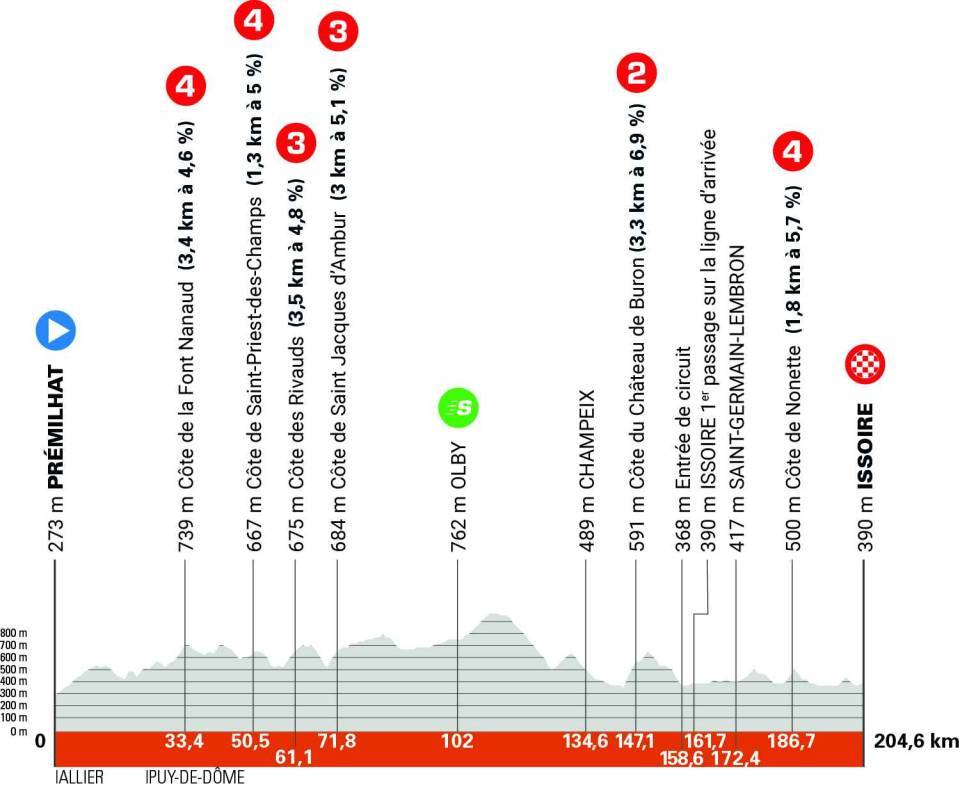

Stage 2

A sprint stage? Sure, but a test of summer form for any sprinters starting the race. The two climbs before the finish rise feature ruined castles. The second to Nonette can eject some sprinters, think of the Namur citadel in the GP Wallonie, minus the cobbles but a dash uphill to a fortified town.

Stage 3

A start in Romain Bardet’s birthplace in order to give him a send-off into retirement and then up into the Forez, the wooded mountains of Auvergne and across to the Rhone valley. The late climb of Château Jaune is new today but we’ll see it before as it’s one of the “wall” climbs that features in Paris-Nice’s Stage 4 this March.

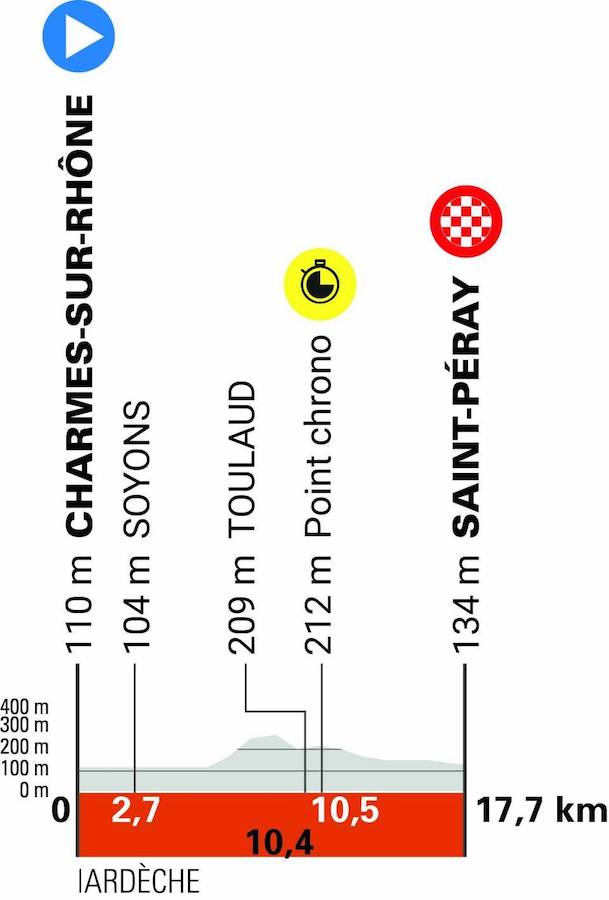

Stage 4

A time trial stage and short too. It’s by the Rhone valley and scenic. The hairpin bends on the climb to Toulaud look good for spectators.

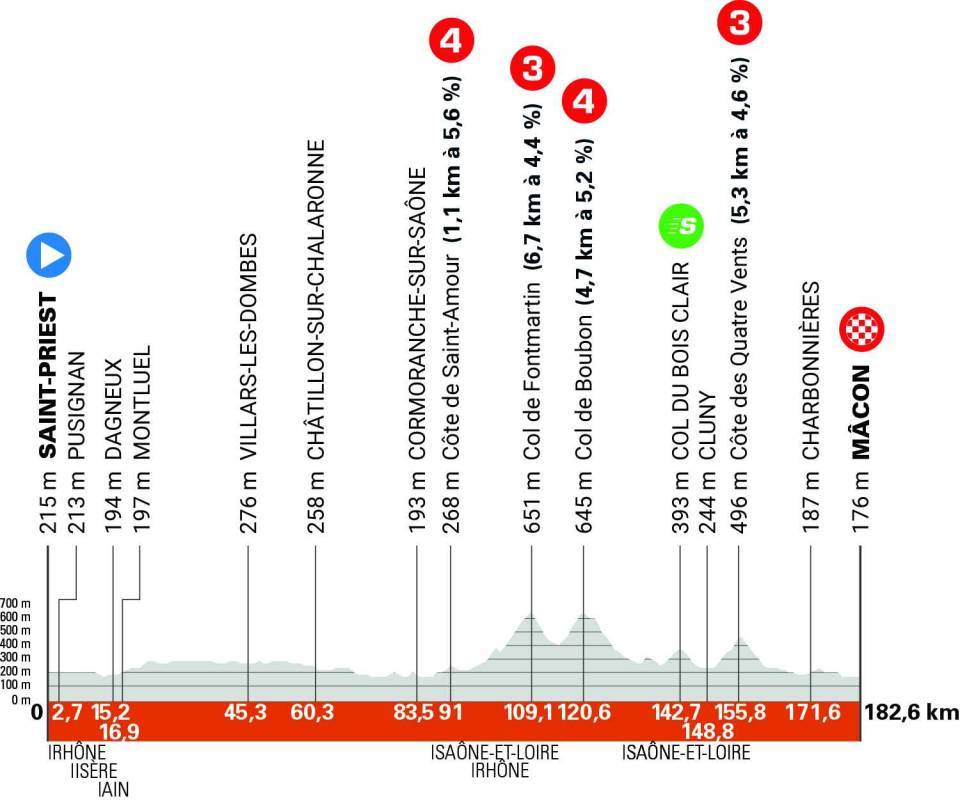

Stage 5

Remember last year’s race? Saint Priest was due to be the finish of Stage 5 but racing was halted after a mass crash downhill so the race dutifully returns for a start. Then it’s across to the Mâcon via the Beaujolais hills, another test for the sprinters with some climbs late on. The Quatres Vents (“four winds” is a col rather than just a côte but it’s not hard and there’s time to regroup for the finish.

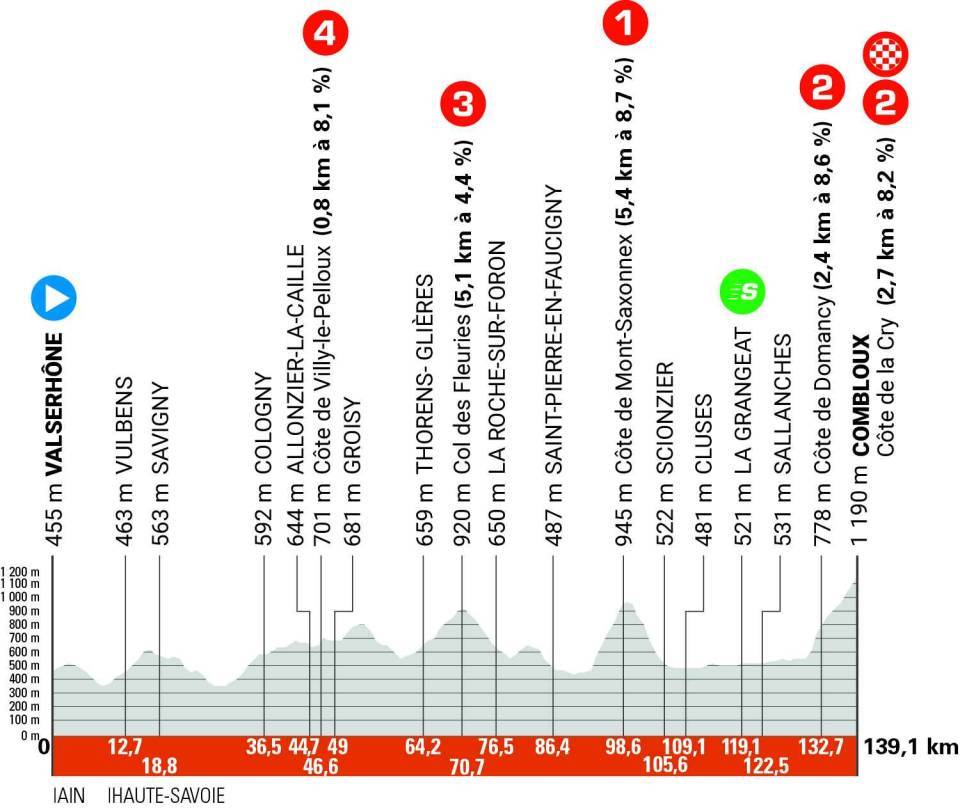

Stage 6

No professional bike race has ever started or finished in Valserhône but if the place looks familiar that’s because the town used to be called Bellegarde, the Dauphiné, Tour de France and more have gone through many times. The stage visits recently-used roads of the Dauphiné and Tour, Mont Saxonnex featured in the 2022 Tour and it’s a tough climb with lots of 10-12% sections but there’s a long valley road to the Domancy climb and to Combloux, where Jonas Vingegaard ransacked Tadej Pogačar in the 2023 Tour. But this time the road goes out of town and uphill to the Cry ski lifts on a steep road that suits punchy riders.

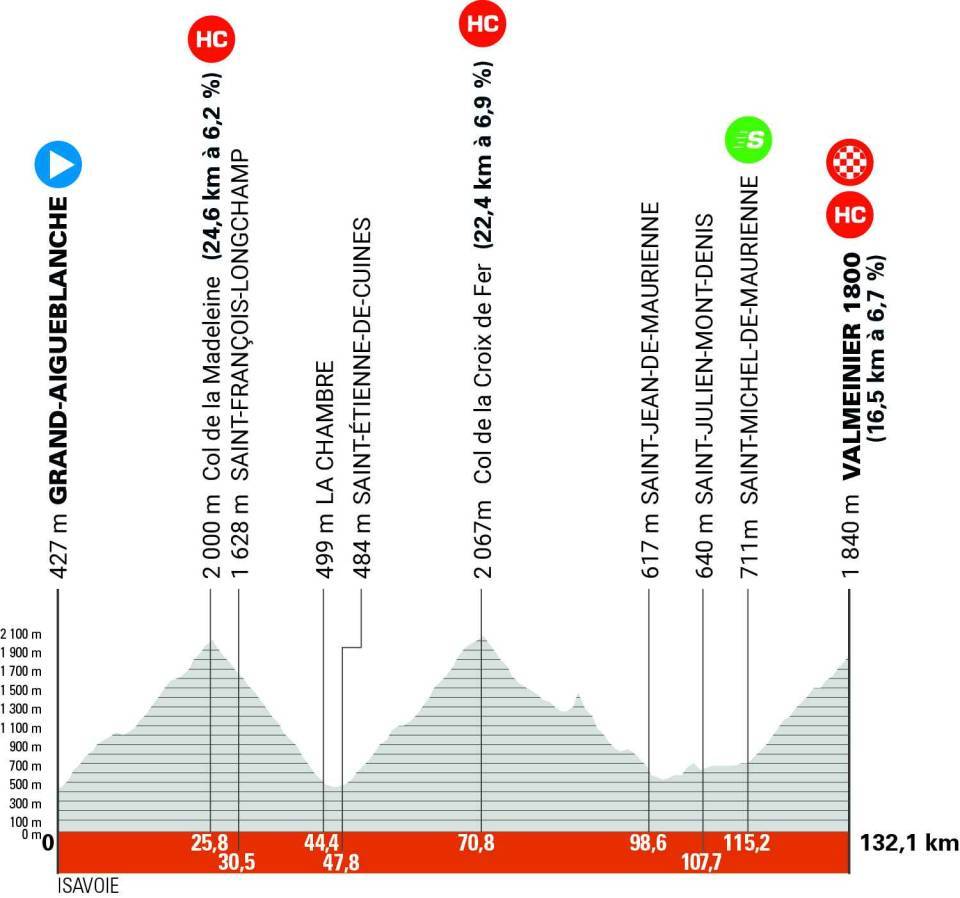

Stage 7

A big day in the Alps. It’s only 132km but there’s little rest, a quick calculation says close to 5,000m of vertical gain, a lot. The Madeleine and Croix-de-Fer are scaled via the main routes, no backroad surprises. The final climb to Valmeinier might be “only” 6.7% average but that’s because a small descent two thirds of the way up that the profile doesn’t quite show, so most of the time the road is a steady 7-8%.

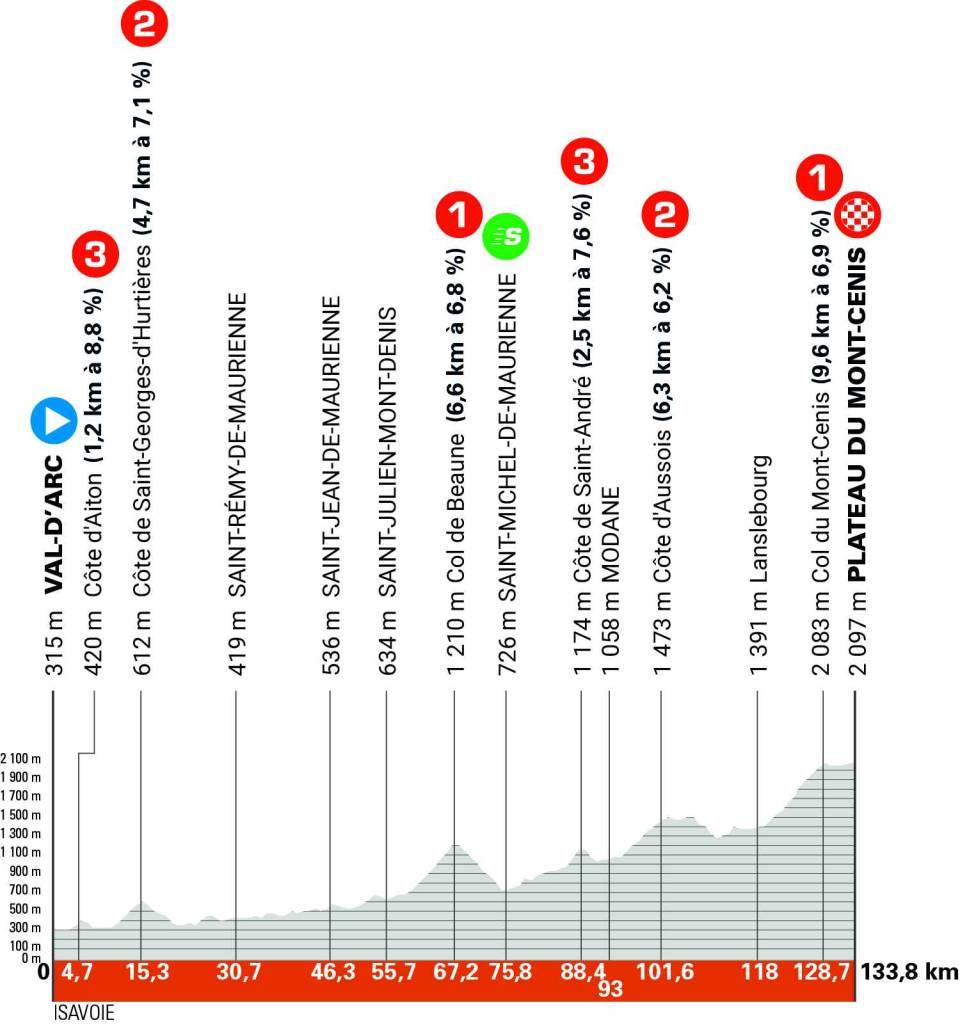

Stage 8

A stage that rides up the Maurienne valley, a rare place that doesn’t get its name from its river (the Arc in case you need to know). The race treats the valley like a boarder in a halfpipe, swinging up the sides to avoid the main valley roads, notably with the climb of the “Col de Beaune”, which is actually the Col de Beau Plan, and featured in 2019 when Julian Alaphilippe won the stage finishing just below.

Mont Cenis was turned into a main road by Napoleon and the big road retains an engineered feel and it’s a steady climb. The route flattens out to finish by the lake on the Italian border, it should look scenic and this route suggests Mont Cenis could be back in the Tour de France.

Verdict

A classic Dauphiné of the recent genre, it’s a tour of the Auvergne-Rhone-Alpes region and each year the race gets closer to a name change. The sprint stages are tricky and the mountain stages short.

The surprise this year is the time trial is short too and because it’s hilly, no dress rehearsal for the Tour’s Caen stage. The final three stages in the Alps have variety with Saturday’s stage the big day on paper to the point where Friday and Sunday are lighter, there are no back-to-back big days.

Gratin dauphinois

Tadej Pogačar and Jonas Vingegaard are due to meet for the first time here so that’s the headline contest. Vingegaard has won here before taking the Tour; Pogačar back as he rattles through his World Tour bucket list.

Remco Evenepoel is scheduled to ride too but he might find third place on the podium is a tough ask as the short time trial doesn’t give him much of a boost; but the main thing to hope is he and the others are back and healthy.

At the other end of the startlist Lotto have declined their right to an invitation meaning TotalEnergies, Tudor and Uno-X all get a wildcard invite. The Belgian team can do the Tour de Suisse for an Alpine race in June but once again if they want to be back in the World Tour next year, they’re avoiding it this year.

Just as the TDF route looks like it concedes some fine advantage to Vingegaard, in this case it’s totally Pogi terrain, even more so when you compare it to older and more typical Dauphiné routes.

It will add a lot of strategic interest to the challenge, the level of wild guessing among fans will reach a new high between the two races!

Even if in recent years some “groundbreaking” schools of thought in training made a strong form at Dauphiné compatible with a dominant TDF, too, nonetheless it’s always a tough call. Even Armstrong had gone too deep in 2003 in order to (successfully) counter the feared Iban Mayo, but then paid it at the TDF: in fact, the following season he definitely chose a more prudent path, accepting to be crushed at the Dauphiné in order to cruise through the TDF at a supernatural level once more.

Pogi is a crazy competitor and will be tempted to hit high form soon to take advantage of the course and add up a new race plus a further victory on Vingo. But it might cost him quite a lot later in July… he’s already got a jigsaw puzzle calendar which is a challenge in itself, let alone if he adds the “competition factor”.

OTOH, Vingo already showed that he can be at top form at both races, so he’ll be a tough competitor anyway despite a course more favourable to Pogi. But it’s also possible he even takes the smarter and calmer path, just honing form at Dauphiné without caring too much about the result, then allowing Pogi to get wilder and wilder in the Classics-like first half of the TDF, just to then bring him down once the big mountains come and the Slovenian form starts to fade or shows some cracks.

All in all, it’s not bad for Remco, either, even if the ITT is too short and stage 7 quite menacing. It could become very interesting if he goes creative. Wasn’t it for the accident (but maybe it won’t be an obstacle, either) he might decide to enter this race full form and try to beat the big two that way, if they don’t do the same, just assuming that another podium at the TDF would be good enough. It would work in marketing terms. But last season left the sensation that it wouldn’t be the best for his body, which arrived better at the TDF after a suboptimal Dauphiné: indeed, for now he looks to be working in an athletically more traditional manner.

However, I like the course as such, even if it lost part of its original touch. Now it’s more of a mini-GT rather than a mountains-only race (or nearly so) as it often looked like. We’ll see how it works, for this specific year, as I explained above, it looks just perfect in order to raise interest.

Re: Armstrong v. Iban Mayo at the Dauphine is 2003/4.

Lots of people look at how racing was in the “drug era” (roughly 1990-2007) and think that says something about racing preparation now, which as far as we know is clean. But it really doesn’t. I think this is worth explaining.

Blood-doping or EPO worked by temporarily raising the blood levels (the ability to transport oxygen). But when the levels are elevated, the body tries to return to “normal” levels. So what happens is that elevated levels last only a short time (like a month). During the “drug era” riders would decide which races they would target and at these races the raised their blood levels. When they had raised blood levels they could try to win the race, but at normal levels they could not compete for the win. But they only had these elevated levels for about a month. This meant they could not have a high performance at both the Dauphine and the Tour (or at the Giro and the Tour).

Since in modern races the riders are not manipulating their blood levels like this, they are at their “natural” level all year. If their natural level results in a high level of performance, they can compete for the win all year round. That is, they can win both Dauphine and Tour (or Giro and Tour). The fact that performance does not fluctuate widely over the season is a good reason to believe they are racing clean.

‘This meant they could not have a high performance at both the Dauphine and the Tour (or at the Giro and the Tour).’

But Indurain won the Giro and the Tour in 92 and 93. Pantani won both in 98.

I also don’t necessarily think that this is the case: ‘The fact that performance does not fluctuate widely over the season is a good reason to believe they are racing clean.’ – because drug technology has advanced by 30 years.

I think we have no idea how clean riders are now.

Indurain and Pantani were in the peak EPO era rather than blood bags, weren’t they? Might have been different parameters then.

Different from what?

(Scratching my head)

By the way, bags & EPO as a dominant method (never separated from other hormones, i.e. corticosteroids, a range of sexual hormones, GH etc.) went on alternating and combining each other through 20+ years (bags, EPO, bags again, CERA/micrododing, bags again…), with Armstrong being a champion of both with no manifest change in the sort of prep or performance curve.

Way off topic. Back to June’s route please.

The Indurain case.

The dosages were still quite low in the early 1990s, which made it easier to peak twice. Indurain was an “early-adopter”. Pedantically, since EPO wasn’t against the rules he could argue he was not technically doping. It took until 1994/95 before pretty much everyone was doping and the dossages became much higher. Riis was in 1996, when the dossages of EPO became absurd. This meant Riis could finish OTL on a mountain stage at the Tour de Suisse, and podium the Tour weeks later. By the Armstrong era it really was practically impossible to double-peak. There is a reason that Armstrong turned up for the Tour and more-or-less skipped the rest of the season. And this became the accepted approach to the season.

We don’t know for sure that there is no doping in the current peloton. But if they are doping it doesn’t look anything like 1990-2007. We know that since performace doesn’t wildly flucatuate over the season (see Riis above). The benefits of doping are almost certainly much lower (or negligible), if it exists.

Only, we have some detailed “training” tables by Fuentes with substance assumptions/blood transfusions and it frankly looks like that, at least with him, it simply didn’t work as you explain here (which I anyway assume to be a simplified version of the underlying ideas)…

Out of sheer curiosity, I’d like to know the source of these conjectures, if available.

I can only point out, as a mere example, that the above doesn’t explain why Lemond and Fignon, i.e. the last set of big TDF winners who probably weren’t involved in serious blood doping, do show a similar pattern of modest/reduced performance at Dauphiné (or Suisse, Midi-Libre, Aude, etc.) before a TDF peak. Even Hinault himself, who could appear to be the one and only exception then, as he could make the double twice, essentially because of his astonishing superiority at the time (1979-1981), used to race at lower level before the TDF and presents much more often than not (add Luxembourg, Sweden etc.) clear examples of having a way lower condition before the TDF.

Similarly, also Roche shows a neat inverted proportion between Dauphiné and TDF final GC results.

The same as above is very evident in Delgado’s case, even if he never raced Dauphiné but preferred Suisse or Midi-Libre.

Obviously I’m not implying all them were “clean” (just as it wouldn’t be very prudent to assume current peloton is “clean”), but surely the technology wasn’t the same or not as perfected (to say the least) as in the following two decades, and yet the form-preparation-performance pattern was the same as later on which contrast starkly with your theory.

Afterwards, a neat change only happened with Team Sky, which, on the other hand, I wouldn’t claim to be a model of clean cycling, even if blood doping hints – although present – are more limited than other evidence on them.

A minor correction: Pogačar raced the Critérium du Dauphiné in 2020. It’s just that his performance was lackluster (he was fourth, but more because of consistent than amazing performance) and did not foreshadow at all what happened a month later.

Quite right, remember it now of course, possibly didn’t think he’d done it before because he hasn’t won it. Will redo the sentence above.

“possibly didn’t think he’d done it before because he hasn’t won it”

Seriously high standards there!

“– – Montluçon, birthplace of Roger Walkowiak and where Julian Alaphilippe” grew up and where his brother runs a bike store?

Yes, that’s the place. His brother Bryan co-founded the store and no surprise to see it trading on the famous name as the “Alaphilippe Bikestore”.

>”Mont Saxonnex featured in the 2022 Tour”

That was in 2021 before Romme and Colombière. Vingegaard crashed on its descent and Pogačar distanced all rivals by a monstrous margin.

The very first part of the climb is the same as for Plateau de Solaison which did feature in 2022 (in Dauphiné where Vingegaard and Roglič finished 1-2).

Is it unusual that a one week stage race has more ascents to 2000m than a three week grand tour? (Three in this parcour vs one in this year’s Giro.)

It’s quite much unusual for the Giro to have so few ascents above 2,000 mts, more than anything. It happened before, but rarely so, as 2,000 mts mountain passes always were an identity mark for the Giro.

But as the negative snowball impact of the Hansen’s show had become too disruptive (towns don’t want to sign for a route which might be cancelled, with Livigno hitting a new bottom line in relationships with municipalities, even if the worst image impact to me is still 2023, with riders filming from the bus how normal people on normal supermarket bikes were riding the route they refused to), well, now organisers decided to stay low in order to reduce that risk.

I don’t agree with such a decision, given that, as inrng explained very well, Hansen & C will simply go on harming by any means the combination of biggest/weakest thing they can be able to, in order to simply prove “that they can”, i.e., to gain political capital (which hasn’t been spent in any meaningful way for now, but whatever… the revolution is always tomorrow).

Luckily, Italy still grants plenty of options, but I believe that it’s the sport as such which is losing a lot, both in sporting and image terms.

Thanks for your reply. I only saw the Giro for the first time in 2020, since it’s not available free to air in the UK, but the stage that remains with me from that edition was the ascent of the Stelvio. So I agree it would be a pity if there aren’t as many of the big mountain stages in the Giro going forward.

I think it’s unfair to lay blame at Hansen and the riders union for recent debacles at the giro. In everything I have read riders were broadly in support of decisions. Even most journalist etc on the ground in Livingo that I heard thought it was the correct decision. I have absolute sympathy for a mayor and other organisers who have paid for a stage start, but it does seem the Giro and RCS are among the worst at making difficult decisions early and communicating them well. I also think we have to look at climate change as a bigger problem than laying blame at the CPA. I can’t see weather improving so stage cancellations can only be more likely.

I think you’re ill informed to say the least, probably because the journalists on the ground you’re referring to belong to a biased context.

The whole thing has been examined in detail here so I won’t delve into it again, but let’s just say that in Livigno the decision as such was potentially acceptable, only it was the CPA which deliberately prevented effective action changing their demands repeatedly and with no external new factor despite having agreed on a set of solutions. Current RCS management led by Vegni is among the most prone ever to listen to the riders, and that’s precisely why they suffer this sort of bullying.

But this isn’t even the core question, just a tipping point because of its consequences.

The core question is that in 2020, 2021 and 2023 we had stages reduced or cancelled with no minimum acceptable reason whatsoever, and that in all those situations riders and teams were well far from broadly supporting the process, which was team-led and lacked transparency and/or decent participation.

Climate change has little relevance in all the above situations because the weather was totally normal, well within any historical record, and it was absolutely possible to race without special risks.

What we are witnessing is just a “climate change” within cycling, teams gaining more power over organisers *and over riders* (whom they pay more, but taking away from them many previous “privileges”), hence powerful teams are just establishing a pattern of behaviour to make sure that they decide how to race, especially (but not exclusively) reducing those factors which would make the competition less of a predictable optimised watts exercise.

(As a side note, the whole fuss about long stages is really about allowing one or two single teams to control a whole race.)

And if you want to read a third party opinion not belonging to Italian or English language press, may I suggest you look for and read what Jorge Matesanz wrote on the subject.

I defer to your local knowledge and better language skills. I am mainly limited to English language press to be fair but do follow those that report other countries. I also appreciate the climate change joke. I accept that riders now have more power but in the past they really had none. Everyone loves the Hampsten Stelvio but I think most riders have said since those conditions were unreasonable looking back. I think we can agree we don’t want the largest teams calling to shots. What I think we need is open dialogue between teams, riders, organiser, and even the UCI to create a better sport. I think the CPA have upped their game under Hansen but accept they may not have got everything right.

This is exactly it, Gabriele. The problem is that the English-speaking media – especially Discovery/Eurosport – present whatever Hansen says as fact, and present the riders (and teams) as unified, and present these as 100% legitimate safety concerns.

And therefore many believe this unquestioningly, particularly in the Anglo nations, and even when they are looking at a race that has been cancelled due to rain or it being ‘too long’.

It’s clearly a powerplay by Hansen, but again is entirely presented as the riders standing up for their rights.

We’re always told that this is a ‘democratic’ process and that ‘all the riders voted in favour of this’ – it is never mentioned that it is one rider from each team that votes (not ‘all of the riders’) and that the vote is not secret. The idea that this rider then does what their team mates want, rather than what their team/employer wants is contemptible.

@Bilmo

Fair. I’d always opt for athletes having more power within the model as a way to achieve better solutions under many respects, and not only for them themselves but for all the environment. But that is precisely what I’m doubting about in current CPA’s case – teams having more power, not riders: yet, I’m ready to hold my judgement as for the general strategy. The latter doesn’t change my opinion on the specific cases. I’m no fan of Hampsten’s Gavia but it should be fair to admit that there’s a lot of distance between that and the situations we’re speaking about, both in terms of actual weather conditions and in terms of available technology and support. Mixing up extremely different situations or concepts (safety/confort) can’t help any reasoned dialogue among parts (I’m referring to those conflicts/conversations, not ours!, which are luckily open enough).

Finally, let me insist on a personal battle. I can’t support any agent who speaks of “safety” and never spends their political credits to fight for actual road safety in the general traffic, which is where the athletes do spend most of their time (training) and where several of them, mainly but not exclusively the more fragile ones, are killed every year.

Last year a 17 yo was killed in Trentino. That summer a local junior girl dedicated her most important victory to his memory. Six months later she was killed at 19 while training with her brother by a driver who hit her frontally while overtaking despite having admittedly seen the cyclists. I’m speaking of federated athletes.

Looks a great parcours but sadly I, like most people in the UK, Ireland, Spain and Estonia won’t be able to watch it or most cycling as Eurosport shuts in our regions – soon to be followed by all of Europe.

Could you please share the info about Spain?

Last season I spent most months abroad and I’m not updated about watching options in Spain. If it’s going to be the same as UK, I’m going to find myself soon in the J_Evans spot (wouldn’t & couldn’t pay). Should we perhaps start to think it’s a conspiracy by wealthier inrng’s commenters who got fed up with us? 😛

However, usually RTVE (public broadcaster) bought the whole ASO package, including Dauphiné and I’d be shocked by a change in strategy given both the ties between ASO and Spanish political institutions *and* how aware ASO are about the importance of going on air for free on a national level.

The above, anyway, is far from being a solution of sort, as it makes you very aware as a cycling fan on how much cycling still sits outside the ASO package, even if you only speak of male/road (no Giro, no Sanremo, no Ronde, no Lombardia, no Tirreno, no Strade Bianche, no Amstel, no GW, no Brabantse, no Autumn Classics, no Suisse, no Itzulia, no Catalunya, no Burgos, no ToA, no San Sebastián…).

Similarly not seen the bad news for Spain, which looks to have Eurosport on Max at a more affordable price.